Family in the Soviet Union

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

The view of the Soviet family as the basic social unit in society evolved from revolutionary to conservative; the government of the Soviet Union first attempted to weaken the family and then to strengthen it from the 1930s onwards.[1]

According to the 1968 law "Principles of Legislation on Marriage and the Family of the USSR and the Union Republics", parents are "to raise their children in the spirit of the Moral Code of the Builder of Communism, to attend to their physical development and their instruction in and preparation for socially useful activity".

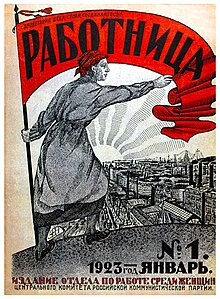

Bolshevik women in the Soviet household

Prior to the 1917 revolution, women did not have equal rights to men and, since most of the population were peasants, they lived under the patriarchal village structure; they had to take care of the home as well as playing an important role in looking after farms. Millions of peasant men did seasonal work in the cities, often leaving women without their husbands for months at a time.[2]

One of the main aims of the Lenin period was to abolish the bourgeois family, and free both men and women from the drudgery of housework. Communal canteens, laundry services and nurseries were set up, and women could now legally get an education and work. The Bolshevik government did not trust the nuclear family, believing it taught individualist, bourgeois values to children; they initially believed that government institutions could raise the millions of children orphaned by the Russian Civil War, and that these children could be inculcated with socialist values.[3] The Civil War had left a void in the industrial sectors of the workforce, and that void was filled with hundreds of thousands of women. When Stalin came to power and instituted the first five-year plan, women's labour became an essential economic resource that allowed a massive expansion of the workforce at a low cost, as women often were not paid as much, in part due to inexperience.[4] They also offered opportunities for women inside of the party when the Department for Work Among Women was created in 1919.

The Bolsheviks advocated for the abolition of differentiated gender roles. Despite this strong push for change by the Zhenotdel, the immensely patriarchal society that had existed for hundreds of years prior, would supersede these efforts.[5]

The feminist movement was seen by the majority peasant and workforce population as bourgeois, and therefore represented something opposite of the Bolshevik idea. The emphasis on the immediate household as priority was pertinent, especially to the 1930s era of Soviet Russia. Since the Paleolithic era of Russia, there has been a fascination with the immortalization, of the mother figure. "The Motherland Calls", statute spoke up about the unrealistic expectations that the Soviet Union had on their female mothers. Motherhood, they posited, was not some divine consciousness, but instead something inherently learned as a result of being a woman. Some argued that the traditional role of the mother should be challenged, and that it was not like it had been in years past. In many instances the domestic work was piled onto the female head of the house, despite promotion of equality between genders. This left in unequal workload on the woman, who would also have a job outside of the home to help provide in a particularly difficult economy where food and adequate housing was often scarce. However, despite this argument, the role of the Bolshevik woman remained static. Stalin himself held both men and women to the same standard, with equal harshness doled out to both sexes. In the 1960s, it was expected of the Russian woman to fall in line with the patriarchal leadership of her husband. [6]

Another heavily relied on role that women held in the Soviet household was that of the Grandmother. In many cases, she would do all the housework and raise the children. This was because the parents were usually too busy working to do either of these. This ended up hurting the installment of Soviet values into the minds of the youth, as the Grandmother would usually teach her grandchildren more traditional values. [7]

Bolshevik vision of the family

Marxist theory on family established the revolutionary ideal for the Soviet state and influenced state policy concerning family in varying degrees throughout the history of the country. The principals are: The nuclear family unit is an economic arrangement structured to maintain the ideological functions of Capitalism. The family unit perpetuates class inequality through the transfer of private property through inheritance. Following the abolition of private property, the bourgeois family will cease to exist and the union of individuals will become a “purely private affair”. The Soviet state’s first code on marriage and family was written in 1918 and enacted a series of transformative laws designed to bring the Soviet family closer in line with Marxist theory.[8][5]

1918 Code on Marriage, the Family and Guardianship

One year after the Bolsheviks took power, they ratified the 1918 Code on Marriage, the Family and Guardianship. The revolutionary jurists, led by Alexander Goikhbarg, adhered to the revolutionary principals of Marx, Engels, and Lenin when drafting the codes. Goikhbarg considered the nuclear family unit to be a necessary but transitive social arrangement that would quickly be phased out by the growing communal resources of the state and would eventually “wither away”. The jurists intended for the code to provide a temporary legal framework to maintain protections for women and children until a system of total communal support could be established.[5]

The 1918 code also served to recognize the legal rights of the individual at the expense of the existing tsarist/patriarchal system of family and marriage. This was accomplished by allowing easily obtainable “no-grounds” divorces. It abolished “illegitimacy” of birth as a legal concept and entitled all children to parental support. It abolished the adoption of orphans (orphans would be cared for by the state to avoid exploitation). A married couple could take either surname. Individual property would be retained in the event of divorce. An unlimited term of alimony could be awarded to either spouse, but upon separation each party was expected to care for themselves. Women were to be recognized as equal under the law; Prior to 1914, women were not allowed to earn a wage, seek education, or exchange property without the consent of their husband.[5][9]

Family Code of 1926

The 1918 code accomplished many of the goals that the jurists had sought to set into motion, but the social disruption left in the wake of World War I exposed the inadequacies of the code to alleviate social problems. The 1926 code would revive a more conservative definition of the family in a legal sense. “The 1918 code had been motivated by a desire to lead society forward to new social relationships in line with socialist thought on marriage and family, the 1926 code attempted to solve immediate problems, in particular to ensure the financial well-being”.[9] The hotly debated social concerns included: the unmanageable number of orphans, the unemployment of women, the lack of protection after divorce, common property and divorce, and the obligations of unmarried, cohabitating partners.

In 1921 alone, seven million orphans were displaced, roaming town and countryside.[10] Government agencies simply did not have the resources to care for the children. An adopted child could be cared for by a family at virtually no cost to the state. The 1926 code would reinstate adoption as a solution for child homelessness.

In 1921 New Economic Policy (NEP), brought about a limited restoration of private enterprise and free markets. It also brought an end to labor conscription. The result was a spike in female unemployment as “War Communism” came to an end and NEP emerged.[6] Hundreds of thousands of unemployed women did not have registered marriages and were left with no means of support or protections following a divorce under the 1918 code. The 1926 code would make unregistered marriages legal in order to safeguard women by extending alimony to unregistered, de facto wives, the purpose being that more women would be cared for in times of widespread unemployment.

Under the 1918 code, there was no division of property in the event of a divorce. Marriage was not to be an economic partnership and each party was entitled to individual property. This meant that women who ran the household and cared for the children would not be entitled to any material share of what the “provider” had brought to the marriage. In another conservative move, the 1926 code would require an equal division of property acquired during a marriage. All property acquired during the course of a marriage would become “common”.[6] With intentions similar to the legal recognition of de facto marriages, this new property law was a response to the lack of protections offered to women in the event of divorce.[11]

Additionally the code would do away with the 1918 concept of “collective paternity” where multiple men could be assigned to pay alimony if the father of a child could not be determined. According to the 1926 code, paternity could be assigned by a judge. It also enlarged family obligations by expanding alimony obligations to include children, parents, siblings and grandparents. Alimony would also have set time limits.[9] The 1926 code would signal a retreat from many policies that served to weaken the family in 1918. The jurists were not pursuing an ideological maneuver away from socialism, rather than taking more “temporary” measures to ensure the well-being of women and children since communal care had yet to materialize.[9]

Family Code of 1936

Unlike earlier codes that arranged for temporary and transitive laws as a step toward the revolutionary vision of family; the Code of 1936 marked an ideological shift away from Marxist / revolutionary visions of the nuclear family.[12] Coinciding with the rise of Stalinism, the law demanded the stabilizing and strengthening of the family. “The “withering-away” doctrine, once central to socialist understand of the family, law, and the state, was anathematized.”[5]

The 1936 code emerged along with an eruption of pro-family propaganda.[12] For the first time, the code put restrictions on abortion and imposed fines and jail time for any that received or performed the service. The code also enacted a bevy of laws aimed to encourage pregnancy and child birth. Insurance stipends, pregnancy leave, job security, light duty, child care services and payments for large families. In another drastic move, the code made it more difficult to obtain a divorce. Under the code, both parties would need to be present for a divorce and pay a fine. There could be harsh penalties for those who failed to pay alimony and child-support payments.[5]

“Our demands grow day to day. We need fighters, they build this life. We need people.”[5] The wider campaign to encourage the family unit elevated motherhood to a form of Stakhanovite labor. During this time, motherhood was celebrated as patriotic and the joys of children and family were extolled by the country’s leaders.

Family Edict of 1944

The Family Edict of 1944 would be a continuation of the conservative trending of the 1936 code. Citing the heavy manpower losses and social disruption following World War II, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet enacted laws that would further encourage marriage and childbirth.

The 1944 Edict offered greater state-sponsored benefits to mothers, including: Extended maternity leave, increased family allowances even to unmarried mothers, promises of burgeoning child care services, targeted labor protections, and most notably, state recognition and the honorary title “Mother Heroine” for mothers who could produce large families.[13]

The edict also sought to preserve the family unit by making divorces even more difficult to obtain. Fines were increased and the parties were often ordered to attempt reconciliation. Divorce also became a public matter. Divorcees were required to appear in public court and their intent was published in the local newspaper.[14]

Evolution of the Soviet family

The early Soviet state sought to remake the family, believing that although the economic emancipation of workers would deprive families of their economic function, it would not destroy the institution but rather base family relations exclusively on mutual affection. The Bolsheviks replaced religious marriage with civil marriage, divorce became easy to obtain, and unwed mothers received special protection. All children, whether legitimate or illegitimate, had equal rights before the law, women gained sexual equality under matrimonial law, inheritance of property was abolished, and abortion was legalized.[15]

In the early 1920s, however, the weakening of family ties, combined with the devastation and dislocation caused by the Russian Civil War (1918–21), resulted in nearly 7 million homeless children. This situation prompted senior Bolshevik Party officials to conclude that the State needed a more stable family life to rebuild the country's economy and shattered social structure. By 1922 the government allowed some forms of inheritance, and after 1926 full inheritance rights were restored. By the late 1920s, adults had been made more responsible for the care of their children, and common-law marriage had been given equal legal status with civil marriage.[15]

During Joseph Stalin's rule (late 1920s to 1953), the trend toward strengthening the family continued. In 1936 the government began to award payments to women with large families, banned abortions, and made divorces more difficult to obtain. In 1942 it subjected single persons and childless married persons to additional taxes. In 1944 only registered marriages were recognized to be legal, and divorce became subject to court discretion. In the same year the government began to award medals to women who gave birth to five or more children and took upon itself the support of illegitimate children.[15]

After Stalin's death in 1953, the government moved in a more liberal direction and rescinded some of its natalist legislation. In 1955 it declared abortions for medical reasons legal, and in 1968 it declared all abortions legal, following Western European policy. The state also liberalized divorce procedures in the mid-1960s, but in 1968 introduced new limitations.[15]

In 1974 the government began to subsidize poorer families whose average per-capita income did not exceed 50 rubles per month (later raised to 75 rubles per month in some northern and eastern regions). The subsidy amounted to 12 rubles per month for each child below eight years of age. It was estimated[by whom?] that in 1974 about 3.5 million families (14 million people, or about 5% of the entire population) received this subsidy. With the increase in per-capita income, however, the number of children requiring such assistance decreased. In 1985 the government raised the age limit for assistance to twelve years and under. In 1981 the subsidy to an unwed mother with a child increased to 20 rubles per month; in early 1987 an estimated 1.5 million unwed mothers were receiving such assistance, or twice as many as during the late 1970s.[15]

Family size

Family size and composition depended mainly on the place of residence—urban or rural—and ethnic group. The size and composition of such families was also influenced by housing and income limitations, pensions, and female employment outside the home. The typical urban family consisted of a married couple, two children, and, in about 20% of the cases, one of the grandmothers, whose assistance in raising the children and in housekeeping was important in the large majority of families having two wage earners. Rural families generally had more children than urban families and often supported three generations under one roof. Families in Central Asia and the Caucasus tended to have more children than families elsewhere in the Soviet Union and included grandparents in the family structure. In general, the average family size followed that of other industrialized countries, with higher income families having both fewer children and a lower rate of infant mortality. From the early 1960s to the late 1980s, the number of families with more than one child decreased by about 50% and in 1988 totaled 1.9 million. About 75% of the families with more than one child lived in the southern regions of the country, half of them in Central Asia. In the Russian, Ukrainian, Belorussian, Moldovian, Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian republics, families with one and two children constituted more than 90% of all families, whereas in Central Asia those with three or more children ranged from 14% in the Kyrgyz Republic to 31% in the Tajik. Surveys suggested that most parents would have had more children if they had had more living space.[15]

Beginning in the mid-1980s, the government promoted family planning in order to slow the growth of the Central Asian indigenous populations. Local opposition to this policy surfaced especially in the Uzbek and Tajik republics. In general, however, the government continued publicly to honor mothers of large families. Women received the Motherhood Medal, Second Class, for their fifth live birth and the Mother Heroine medal for their tenth. Most of these awards went to women in Central Asia and the Caucasus.[15]

Reproduction and family planning

The primary form of contraception practiced in the early USSR was coitus interruptus. Scarcity of rubber made condoms and diaphragms unavailable, and contraception was rarely discussed by political figures.[5]

The U.S.S.R. was the first country in the world to legalize abortion. For many years prior to the October Revolution, abortion was not uncommon in Russia, although it was illegal and carried a possible sentence of hard labor or exile.[16] After the revolution, famine and poor economic conditions led to an increase in the number of “back alley” abortions, and after pressure from doctors and jurists, the Commissariats of Health and Justice legalized abortion in 1920. Abortions were free for all women, although they were seen as a necessary evil due to economic hardship rather than a woman’s right to control her own reproductive system.[17]

Through the 1930s, a rising number of abortions coupled with a falling birthrate alarmed Soviet officials, with a recorded 400,000 abortions taking place in 1926 alone.[16] In 1936 the Soviet Central Executive Committee made abortion illegal once again. This, along with stipends granted to recent mothers and bonuses given for women who bore many children, was part of an effort to combat the falling birthrate.[5]

Family and kinship structures

The extended family was more prevalent in Central Asia and the Caucasus than in the other sections of the country and, generally, in rural areas more than in urban areas. Deference to parental wishes regarding marriage was particularly strong in these areas, even among the Russians residing there.[15]

Extended families helped perpetuate traditional life-styles. The patriarchal values that accompany this life-style affected such issues as contraception, the distribution of family power, and the roles of individuals in marriage and the family. For example, traditional Uzbeks placed a higher value on their responsibilities as parents than on their own happiness as spouses and individuals. The younger and better educated Uzbeks and working women, however, were more likely to behave and think like their counterparts in the European areas of the Soviet Union, who tended to emphasize individual careers.[15]

Extended families were not prevalent in the cities. Couples lived with parents during the first years of marriage only because of economics or the housing shortage. When children were born, the couple usually acquired a separate apartment.[15]

Function of the family

The government assumed many functions of the pre-Soviet family. Various public institutions, for example, took responsibility for supporting individuals during times of sickness, incapacity, old age, maternity, and industrial injury. State-run nurseries, preschools, schools, clubs, and youth organizations took over a great part of the family's role in socializing children. Their role in socialization was limited, however, because preschools had places for only half of all Soviet children under seven. Despite government assumption of many responsibilities, spouses were still responsible for the material support of each other, minor children, and disabled adult children.[15]

The transformation of the patriarchal, three-generation rural household to a modern, urban family of two adults and two children attests to the great changes that Soviet society had undergone since 1917. That transformation did not produce the originally envisioned egalitarianism, but it has forever changed the nature of what was once the Russian Empire.[15]

Diet and nutrition of the Soviet family

The history of the Soviet Union diet prior to World War II encompasses different periods that have varying influences on food production and availability. Periods of low crop yields, and restrictive distribution of food in the early 1920s, and again in the early 1930s brought about great famine and suffering in the Soviet Union.[18] Farming was one of the main efforts for food production, and was at the center of development in support of Soviet communism. When crops failed or suffered from low yields, Soviet peasants suffered greatly from malnutrition. The traditional types of food found in the Soviet Union were made up of various grains for breads and pastries, dairy products such as cheese and yogurt, and various meats such as pork, fish, beef and chicken.[19] By 1940, certain products, such as vegetables, meat and grains, were less abundant than other forms of food due to the strain on resources and poor crop yields. Bread and potatoes were very important staples for Soviet families, both in cities and in the countryside.[20] Potatoes were easily grown and harvested in many different environments, and were usually reliable as a food source. Malnutrition was a prominent factor in poor health conditions and individual growth during this period in the Soviet Union.[21] Much like the Western tradition of three main meals a day, the Soviet meals consisted of breakfast (zavtrak), lunch (obed), and dinner (uzhin). Soups and broths made of meats and vegetables when available, were common meals for the Soviet peasant family.

See also

- Demographics of the Soviet Union

- New Economic Policy

- New Soviet man

- Order of Maternal Glory

- Orphans in the Soviet Union

- Tax on childlessness

References

Citations

- ^ Ward, Christopher Edward (2016). The Stalinist Dictatorship (9th ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 210–211. ISBN 9781317762256.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (2017). The Russian Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780198806707.

- ^ Hoffman, David (2003). Stalinist Values: The Cultural Norms of Soviet Modernity 1917-1941. Cornell University Press. pp. 105–106.

- ^ Lapidus, Gail Warshofsky (2003). "Women in Soviet Society: Equality, Development, and Social Change". In Hoffman, David (ed.). Stalinism: the essential readings. Blackwell. pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Z., Goldman, Wendy (1993). Women, the state, and revolution : Soviet family policy and social life, 1917-1936. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521458160. OCLC 27434899.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Women in Russia. Atkinson, Dorothy, 1929-2016., Dallin, Alexander, 1924-2000., Lapidus, Gail Warshofsky. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. 1977. ISBN 0804709106. OCLC 3559925.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Stalinist Society, Chapter: Family Values, Mark Edele

- ^ Marx, Karl (2012). The Communist manifesto. Engels, Friedrich, 1820-1895,, Isaac, Jeffrey C., 1957-, Lukes, Steven. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300163209. OCLC 794670865.

- ^ a b c d Quigley, John (1979-01-01). "The 1926 Soviet Family Code: Retreat from Free Love". The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review. 6 (1): 166–174. doi:10.1163/187633279x00103. ISSN 1876-3324.

- ^ Goldman, Wendy (1984-11-01). "Freedom and ITS Consequences: The Debate on the Soviet Family Code of 1926". Russian History. 11 (4): 362–388. doi:10.1163/18763316-i0000023. ISSN 1876-3316.

- ^ Warshofsky., Lapidus, Gail (1978). Women in Soviet society : equality, development, and social change. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520028686. OCLC 4040532.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Cultural revolution in Russia, 1928-1931. Fitzpatrick, Sheila., American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies. Research and Development Committee., Columbia University. Russian Institute. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1978. ISBN 0253315913. OCLC 3071564.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union of July 8, 1944". Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ^ Field, Deborah A. (1998-10-01). "Irreconcilable Differences: Divorce and Conceptions of Private Life in the Krushchev Era". Russian Review. 57 (4): 599–613. doi:10.1111/0036-0341.00047. ISSN 1467-9434.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Text used in this cited section originally came from: Soviet Union Country Study from the Library of Congress Country Studies project.

- ^ a b Avdeev, Blum, Troitskaya, Alexandre, Alain, Irina (1995). "The History of Abortion Statistics in Russia and the USSR from 1900 to 1991". Population: An English Selection. 7: 39–66. JSTOR 2949057.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kiaer, Naiman, Christina, Eric (2006). Everyday Life in Early Soviet Russia: Taking the Revolution Inside. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 61–70.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dando, William (1994). "Harvard Ukrainian Studies". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 18 (3–4): 396–397.

- ^ Romero, Gwynn (1997). "Dietary Practices of Refugees from the Former Soviet Union". Nutrition Today. 32 (4): 2–3.

- ^ Zubkova, Elena (2004-03-01). "The Soviet Regime and Soviet Society in the Postwar Years: Innovations and Conservatism, 1945–1953". Journal of Modern European History. 2 (1): 134–152. doi:10.17104/1611-8944_2004_1_134. ISSN 1611-8944. S2CID 147259857 – via SAGE Publishing.

- ^ Brainerd, Elizabeth (2010). "Reassessing the Standard of Living in the Soviet Union" (PDF). The Journal of Economic History. 70 (1): 83–117. doi:10.1017/S0022050710000069. hdl:2027.42/40198. S2CID 15082646.

Notes

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

Bibliography

- Clements, B., & Lanning, R. (1999). Bolshevik women. Science and Society, 63(1), 127–129.

- Wieczynski, J. (1998). Bolshevik Women. History: Reviews of New Books, 26(4), 191–192.

- Marx K, Engels F, Isaac J, Lukes S. The Communist Manifesto. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2012.

- Goldman W. Women, The State, And Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

- Quigley J. The 1926 Soviet Family Code: Retreat from Free Love. The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review. 1979;6(1):166–174. doi:10.1163/187633279x00103.

- Mccauley, Martin. Stalin and Stalinism: Revised 3rd Edition (Seminar Studies) (Kindle Locations 2475–2479). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

- Nakachi, Mie. (2021). Replacing the Dead: The Politics of Reproduction in the Postwar Soviet Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.