Frank Russell, 2nd Earl Russell

The Earl Russell | |

|---|---|

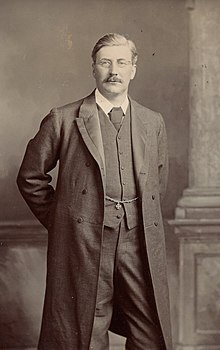

Frank Russell, c. 1901 | |

| Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for India | |

| In office 1 December 1929 – 3 March 1931 | |

| Monarch | George V |

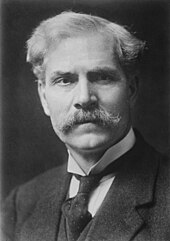

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Drummond Shiels |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Snell |

| Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport | |

| In office 11 June 1929 – 1 December 1929 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | John Moore-Brabazon (1927) |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Ponsonby |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| Hereditary peerage 13 August 1886 – 3 March 1931 | |

| Preceded by | John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (1878) |

| Succeeded by | Bertrand Russell, 3rd Earl Russell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Francis Stanley Russell 12 August 1865 Nether Alderley, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 3 March 1931 (aged 65) Marseilles, France |

| Spouses |

|

| Parent(s) | Viscount and Viscountess Amberley |

John Francis Stanley Russell, 2nd Earl Russell, known as Frank Russell (12 August 1865 – 3 March 1931), was a British nobleman, barrister and politician, the elder brother of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, and the grandson of John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, who was twice prime minister of Britain. The elder son of Viscount and Viscountess Amberley, Russell became well-known for his marital woes, and was convicted of bigamy before the House of Lords in 1901, the last peer to be convicted of an offence in a trial by the Lords before that privilege of peerage was abolished in 1948.

Russell was raised by his paternal grandparents after his unconventional parents both died young. He was discontented living with his grandparents, but enjoyed four happy years at Winchester College. His academic education came to a sudden end when he was sent down from Balliol College, Oxford, probably because authorities there had suspicions concerning the nature of his relationship with the future poet Lionel Johnson, and he always bitterly resented his treatment by Oxford. After spending time in the United States, he married the first of his three wives, Mabel Edith Scott, in 1890. The two quickly separated, and the next several years saw acrimonious litigation in the courts, but the restrictive English laws of the time meant there was no divorce. Russell was elected to the London County Council in 1895, and served there until 1904. In 1899, he accompanied the woman who would become his second wife, Mollie Somerville, to Nevada, where each obtained a divorce, and they married, then returned to Britain to live as husband and wife. Russell was the first celebrity to get a Nevada divorce, but it was not recognised by English law, and in June 1901, he was arrested for bigamy. He pleaded guilty before the House of Lords, and served three months in Holloway, afterwards marrying Mollie according to English law. He gained a free pardon for the offence in 1911.

Beginning in 1902 Russell campaigned for divorce law reform, using his hereditary seat as a peer in the House of Lords to advocate this, but had little success. He was also a campaigner for motorists' rights, often taking briefs to defend them after being called to the bar in 1905, and at one time had the registration number plate A 1. His second marriage ended after he fell in love with the novelist Elizabeth von Arnim in 1914, and he married von Arnim in 1916. The couple soon separated, though they did not divorce, and Elizabeth caricatured him in her novel Vera, to his anger. Frank Russell aided his brother Bertrand when he was imprisoned for anti-war activities in 1918. Increasingly aligned with the Labour Party, Russell was given junior office in the second MacDonald government in 1929, but his ministerial career was cut short by his death in 1931. Despite his achievements, Frank Russell is obscure compared to his brother and grandfather, and his marital difficulties led to his being dubbed the "Wicked Earl".

Early life

John Francis Stanley Russell was born on 12 August 1865 at Alderley Park in Cheshire. He was the first child of John Russell, Viscount Amberley, the eldest son of John Russell, 1st Earl Russell. The earl twice served as prime minister of Britain,[a] and earlier in his career, had been an architect of the Reform Act 1832. In 1864, Amberley married Katherine Louisa Stanley, younger daughter of Edward Stanley, 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley, uniting two prominent Whig families. Alderley Park was the seat of the Stanley family.[2][3]

Unconventional for their time, the Amberleys believed in birth control, feminism, political reforms then considered radical (including votes for women and the working classes) and free love, and lived according to their ideals.[4][5] For example, feeling it unfair that Douglas Spalding, the tutor of their son Frank, should remain celibate, the viscountess invited Spalding to share her bed, with the approval of her husband. The Amberleys had two children after Frank, Rachel (born 1868) and Bertrand (born 1872). The family lived at Rodborough house (near Stroud), which belonged to the viscount's father, and then at Ravenscroft Hall, near Trellech, where Frank was allowed to do much as he pleased, including roaming the countryside. His parents had lost religious faith and Frank was not called upon to attend church. By age eight, he had read, for pleasure, the complete works of Sir Walter Scott, and began a lifelong love of science and engineering by attending the Royal Society's lectures for children.[4]

In December 1873, the family journeyed to Italy; during the return the following May, Frank came down with diphtheria. He was nursed by his mother, and recovered, but in June both she and Rachel fell ill with the disease. The viscountess died on 28 June and her daughter five days later, dealing the viscount a blow from which he never really recovered. He died on 9 January 1876 from pneumonia.[6] The viscount's will nominated T. J. Sanderson, a friend from his university days, and Spalding as co-guardians of Frank and Bertrand. The earl and his wife, Frances Russell, Countess Russell (often referred to as Lady John Russell) might have accepted Sanderson, even though he was (like Spalding) an atheist, but Spalding was of a lower social class and was not acceptable, especially once they had the opportunity to read the Amberleys' surviving papers and learnt the nature of his relationship with the viscountess.[7] The Earl Russell and Lady John brought suit in the Court of Chancery, and Sanderson and Spalding chose not to fight the suit. Frank and Bertrand were placed in the custody of their paternal grandparents, with two of the Russells' adult children, Rollo and Agatha, also co-guardians.[8]

This took Frank from what he later called the "free air of Ravenscroft" where he could wander as he wished, to his grandparents' home at Pembroke House, where he was closely supervised and confined to the grounds. He found the atmosphere stifling – no subject considered vulgar could be mentioned, and he was required to go to church and have religious education.[9] The earl was by then past 80, two decades older than his wife, and spent many of his waking hours reading: the house was dominated by Lady John,[10] who employed a strict moral code in raising the boys.[11] Frank was not allowed much time alone with Bertrand, as he was believed a bad influence on his younger brother,[12] and Frank Russell wrote of Bertrand, "Till he went to Cambridge he was an unendurable little prig."[13] Annabel Huth Jackson, a friend of both boys, deemed Pembroke House, "an unsuitable place... for children to be brought up in."[14] George Bernard Shaw, a half-century later, wrote to Frank of his incredulity that the boy had not murdered his Uncle Rollo and burned the place down.[14]

Education

Frank was sent to Cheam as a boarder in 1876.[15] He was happier at school than he had been at Pembroke Lodge.[16] In his memoirs he remembered his indignation at being addressed by his father's courtesy title, Viscount Amberley, which was now his as heir apparent to the earldom. He was still at Cheam when in 1878, his grandfather died, making Frank the 2nd Earl Russell.[15]

Frank then attended Winchester College, from 1879 to 1883. Winchester became his spiritual home,[17] and he expressed his reverence for the school in his autobiography. George Santayana, who would be a long-time friend of Frank Russell, described Winchester as "the only place he loved and the only place he was loved".[18] Frank briefly became pious while at Winchester, going so far as to be confirmed by the Bishop of Winchester in November 1880. The orphaned earl was taken under the wing of his housemaster, the Revd George Richardson, and his wife Sarah. It was Sarah Richardson that Santayana was thinking of in making his statement; she later defended Frank Russell as his marital problems filled the daily papers, and he was devastated by her death in 1909.[19] At Winchester, Frank spent four of his happiest years and acquired many of the friends he would have in adult life. From about the time Frank began at Winchester, Frank and Bertrand began to spend time with their maternal grandmother, Henrietta Stanley, Baroness Stanley of Alderley, whom they came to like greatly as far less priggish than Lady John.[20] Frank came to find Lady Stanley's London residence at 40 Dover Street a refuge from Pembroke House.[21]

It was at Winchester that he befriended the future poet and critic Lionel Johnson, whom he would describe as "the greatest influence of my life at Winchester".[22] They were friends in Russell's final term at Winchester, and Johnson visited Pembroke House, but the friendship did not truly blossom until Russell went up to Balliol College, Oxford, in 1883.[23] The pair wrote long, earnest letters to each other in which they explored spiritual matters and questions of sin and morality.[24] In 1919 Russell anonymously published Johnson's side of the correspondence as Some Winchester Letters of Lionel Johnson.[25]

At Balliol, Russell read classics. The scholar of classical Greek literature Benjamin Jowett was then Master of Balliol and also Vice-Chancellor of Oxford. Russell found the university stimulating, welcoming the "untrammelled and unfettered discussions on everything in heaven and earth".[26] He wrote to Johnson at Winchester, and after the correspondence was forbidden by Johnson's father, routed his letters through fellow undergraduate Charles Sayle. Russell joined university clubs and other groups, and made satisfactory academic progress through much of his first two years,[27] but his Oxford career was dramatically cut short when in May 1885, as Russell related it in his memoirs, he was sent down by Jowett for supposedly writing a "scandalous" letter to another male undergraduate. Russell denied the charges but was refused a formal inquiry. Incensed at having been falsely accused, he lost his temper with Jowett, telling him he was no gentleman, and left the college.[28] Even after a year, Jowett refused Russell re-admission to Balliol, and refused the necessary recommendation to allow Russell to enter a Cambridge college.[29]

The veracity of Russell's account of his sending-down is open to question; Santayana deemed it a fabrication, based on what Russell had privately told him, but at the core of it was the nature of Russell's relationship with Johnson. In April 1885, Johnson, who had recently turned 18 but appeared younger, stayed overnight in Russell's rooms after missing the last train to London, and, according to Santayana, the authorities had seen the two together and declared Johnson too young to be Russell's "natural friend".[30] Nevertheless, Santayana wrote that the relations between Russell and Johnson had not been "in the least erotic or even playful".[31] In July 1885, two months after Russell was sent down, Johnson's father enquired of Jowett whether Russell was a suitable companion for Lionel, and was told he was not, and that further acquaintance between the two should be forbidden. Russell and Jowett reconciled to some extent, and the master was present at the earl's first wedding in 1890. Russell, though, missed Jowett's funeral in 1893, alleging rheumatism, and remained bitter about the end of his Oxford career for the rest of his life.[32] Santayana stated that any "unnatural desires" on Russell's part did not last, given that he turned out "a perfectly normal pronounced polygamous male".[33]

Early adulthood

He was a tall young man of twenty, still lithe though large of bone, with abundant tawny hair, clear little steel-blue eyes, and a florid complexion. He moved deliberately, gracefully, stealthily, like a tiger well fed and with a broad margin of leisure for choosing his prey. There was precision in his indolence; and mild as he seemed, he suggested a latent capacity to leap, a latent astonishing celerity and strength, that could crush at one blow. Yet his speech was simple and suave, perfectly decided and strangely frank.

—George Santayana's description of Frank Russell in 1886[34]

After his sending-down from Oxford, Russell took a year's leasehold on a small house in the village of Hampton, to which his guardians (he was not yet 21 years old, the age of majority at the time) reluctantly consented on condition a tutor of their choice live with him. Although the monotony of life in the London suburbs was varied by guests such as Oscar Wilde, Russell was resentful at how he had been treated at Oxford and in October 1885, took ship for the United States.[35] He was generally impressed with America, but disliked New York City. On his trip, he first met Santayana, then an undergraduate at Harvard College; he was the first Englishman Santayana had ever met. Russell also met Walt Whitman on his trip across America and back, and visited the president, Grover Cleveland at the White House.[36]

Russell attained his majority in August 1886, and came into his inheritance, allowing him to live on a grander scale. He was not idle, involving himself with an electrical contracting company, a field he had experimented in since his boyhood. This was the first of many commercial enterprises in which he would participate. Like Russell's commercial career as a whole, it had mixed success, ceasing to trade within three years. An expensive lifestyle and fees from the many court actions he was involved in would lead him to describe himself as bankrupt by 1921, and when Frank died ten years later, Bertrand said he had inherited a title from his brother but little else.[37]

First marriage

Although Russell was not wealthy by the standards of British nobility, what he did have, including his title, was enough to make him the target of parents seeking suitable matches for their daughters. Among these were Maria Selina (Lina) Elizabeth, Lady Scott,[b] who sought a suitable match for her daughter, Mabel Edith Scott, and called on Russell in 1889. Santayana recalled that Russell was at first more interested in Selina Scott, a divorcée, than her daughter[39] and theorised that the fact that Russell's mother died when he was a child allowed Lady Scott to overwhelm Russell and persuade him that the way to perpetuate their friendship was for him to marry her daughter.[40]

Frank and Mabel Russell married on 6 February 1890. Three months later, the two separated, Mabel alleging physical and mental cruelty.[41] Santayana later wrote, "Russell as a husband, Russell in the domestic sphere, was simply impossible: excessively virtuous and incredibly tyrannical. He didn't allow her enough money or enough liberty. He was punctilious and unforgiving about hours, about truth-telling, about debts. He objected to her friends, her clothes, and borrowed jewels. Moreover, in their intimate relations he was exacting and annoying. She soon hated and feared him."[42]

Late in 1890, Mabel sued unsuccessfully to judicially separate from him, accusing him in the process of "immoral behaviour" with another university friend, Herbert Roberts, head mathematics tutor at Bath College.[41] The allegations of the trial filled the newspapers.[43] and a jury found in Frank Russell's favour.[44] At the time, the only valid ground for divorce was adultery, although a woman alleging it would also have to show some other offence, such as desertion. With the approval of their families, Frank and Mabel Russell continued to live apart, a tacitly agreed relationship that meant Mabel was unlikely to be able to show desertion.[45] Although there were fitful efforts at reconciliation thereafter, the parties remained apart. In 1892, Russell opened his own firm of electrical engineers, Russell & Co. He began to be seen more in the House of Lords, in September 1893 being one of forty peers who supported the unsuccessful Irish Home Rule bill.[46] Despite the lull in the Russell matrimonial litigation, detectives were active for both sides, hoping to find evidence of adultery which would allow their employer advantage in the courts.[47] By 1894, Frank Russell, as he told his brother Bertrand, was three years into an affair with Mary Morris, a clerk at his electrical works.[48]

Having failed to convince the jury, Mabel subsequently attempted to obtain a separation by indirect means, suing for restitution of conjugal rights in 1894. Under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1884, failure to comply with an order of restitution of conjugal rights served to establish desertion, which gave the other spouse the right to an immediate decree of judicial separation, and, if coupled with the husband's adultery, allowed the wife to obtain a divorce. Such an action also allowed a petitioning wife to seek an allowance. In general, at the time in England, divorces were available only when the petitioning spouse had not offended against the marriage and the other spouse had.[49] The earl countersued on the ground that her accusations since 1891 amounted to legal cruelty. A jury found for Frank Russell in both cases in 1895, but Mabel appealed and the verdict was overturned in the Court of Appeal. The case went all the way to the House of Lords, and the Law Lords affirmed the appeals court decision.[44] This denied them both satisfaction, binding the definition of legal cruelty to physical violence and making Russell v. Russell a case of legal significance for the next seventy years,[c] until divorce law reform eliminated cruelty as a statutory ground for divorce.[50] Another trial took place in 1897 after Lady Scott published accusations against Russell; she was convicted of criminal libel and sentenced to eight months in prison, but Russell was hissed at by the crowds surrounding the Old Bailey after the sentencing, and called the "Wicked Earl".[51]

The Local Government Act 1894 created district and parish councils. In December of that year Russell successfully stood for Cookham Parish Council, and was made chairman, and ex officio a guardian of the poor. He worked to change outdated practices in the workhouse, and to see that roads and rights of way were maintained. In February 1895, he was elected to London County Council (LCC) for Newington West as a Progressive. He aligned himself with the left, joining the Reform Club in 1894, a bastion of Liberalism.[52] He stood unsuccessfully for Hammersmith at the next election, in March 1898, but was made an alderman, continuing him on the LCC,[53] where he remained through 1904.[54]

Nevada divorce

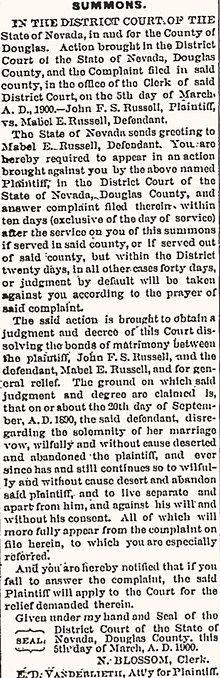

Russell became infatuated with Marion (known as Mollie) Somerville, who was at that time married to George Somerville, with whom Russell had become friendly during the campaign in Hammersmith. The twice-married daughter of a master shoemaker from Ireland, Mollie Somerville had three children and was secretary of the Hammersmith Women's Liberal Association. She campaigned for Russell; the two became close and were seen together at several events. When she fell ill early in 1899, Russell let her use one of his residences, and the two went away together, travelling via France to America. Russell planned to use laxer American divorce laws to end his marriage to Mabel Russell.[55][56]

Russell and Mollie Somerville journeyed to Chicago, but learned that local laws had recently been tightened, and required a year's residence, with other restrictive provisions. North Dakota and Arizona Territory were also considered, and in the latter case visited, but also required living there a year. Nevada, with only a six-month requirement, was more practical. They settled in Glenbrook, on Lake Tahoe, for the winter of 1899–1900. On 14 April 1900 both Russell and Somerville were granted divorces. Their marriage ceremony in Reno before Judge Benjamin Franklin Curler took place on 15 April.[57] They honeymooned on the way to America's East Coast, including at Denver's Brown Palace Hotel, where Russell told a reporter that a charge of bigamy would never stick.[58] The couple returned to Britain the following month.[59]

Russell knew such a divorce was invalid under English law, which refused to recognise foreign divorces obtained by British subjects; his intent was to allow Mabel Russell to obtain a divorce on the grounds of bigamy following adultery, which would also free him to marry again: he deposited £5,000 that would go to her upon a divorce to ensure her cooperation.[60]

Beginning when Russell wired news of his Nevada marriage to appear as a notice in The Times, there was considerable press interest on both sides of the Atlantic in what had occurred. Both Mabel Russell and George Somerville filed for divorce, and each gained them uncontested, subject to the usual waiting period before the decrees became absolute. Russell, on his return, took his seat on the LCC as if nothing had occurred. There was, initially, no other official reaction, society accepted them as a married couple, and Mollie appeared on the 1901 census as "Mollie Russell".[61]

Trial before the Lords

Russell was arrested on a charge of bigamy as he stepped from a train at Waterloo Station on 17 June 1901.[62] Why an action was brought for this rarely prosecuted crime is uncertain.[63] Russell believed that he was prosecuted when, as he related, another nobleman who had acted similarly but was a favourite at Court was not, because he was "an unbeliever and a radical".[64] The Russell family always believed that the earl was prosecuted at the behest of the new king, Edward VII, who had a chequered past and several mistresses while on the throne, to boost his own reputation for morality.[63]

Russell was bailed, and following a hearing at Bow Street Magistrates' Court on 22 June,[65] he was indicted for bigamy by a grand jury and committed for trial.[59] Until the privilege was abolished in 1948,[66] peers and peeresses indicted for treason or felony were tried before the House of Lords, a majority vote deciding the matter.[67] Russell could not have waived trial there had he wanted to,[68] and the verdict of the House of Lords could not be appealed.[69] Such trials were rare: Russell's trial was the first since that of Lord Cardigan, who was acquitted on a charge of duelling in 1841, the previous trial having been in 1776, and only one trial, resulting in the acquittal of Lord de Clifford for manslaughter in 1935, followed before the abolition.[70]

Russell's trial before the House of Lords took place in the Royal Gallery of the Houses of Parliament on 18 July 1901, with some two hundred peers present, including Lord Salisbury, the prime minister.[68] The lords spiritual who were among Russell's judges were William Maclagan, the Archbishop of York and Randall Davidson, the Bishop of Winchester (later Archbishop of Canterbury).[71] Lord Halsbury, the lord chancellor, presided under the king's commission as lord high steward. Also present were Mollie Russell, Judge Curler, and the English clergyman who had performed Russell's first marriage. The assembled peers and judges in their robes were deemed "most picturesque" by The New York Times, which described a "magnificent blaze of color" from the robes of the assembled peers and judges.[68][72] All the Lords of Appeal were present to advise the peers on any legal questions that arose, as were eleven other judges.[73] This required the suspension of the courts over which they would have presided that day, and some newspapers questioned the cost of the spectacle, which included the expense of bringing over Curler from Nevada and housing him for two months.[74]

When Russell's trial began on 18 July, he was called upon to plead guilty or not guilty, but his counsel interposed, and argued that because the wedding had taken place in America, Russell had not violated the bigamy statute. Lord Halsbury dismissed the point without even requiring the prosecution to respond. Russell then pleaded guilty, and made a statement defending his conduct and stating that no one had been injured thereby, and the lords retired to consider their verdict.[72] The House of Lords had the power to disqualify Russell from sitting there in future unless pardoned,[75] but it did not. On the recommendation of Lord Halsbury, Russell was sentenced to three months at Holloway Prison.[76] He wrote in his memoirs that the privilege of peers cost him dearly, as he probably would have been sentenced to a token day in prison at the Old Bailey had he been a commoner. Instead, a great sum of money and considerable effort had been expended to provide him with a trial before the Lords, "and it was necessary that the sentence should bear some relation to the fuss made about it."[77] In anticipation of his arrival, a room for favoured prisoners, previously occupied by the journalist W. T. Stead and by some of the Jameson raiders, had been prepared for him, where he could have his own food and wine.[72]

Russell spent part of his time in prison peppering the home secretary, Charles Ritchie, with petitions for his early release (which he did not gain) and for better conditions and more privileges (which, mostly, he received). He read through the works of Shakespeare, twice,[78] and wrote his first book, Lay Sermons, treating religious and ethical questions from his perspective as an agnostic. His friend, Santayana, was unimpressed with the book, describing it as "the only regrettable consequence" of Russell's incarceration.[79] He was released on 17 October 1901, eleven days before his divorce by Mabel Russell became absolute (George Somerville's divorce of Mollie had become absolute on 24 June). Frank Russell married Mollie according to English law on 31 October 1901.[80]

Frank Russell persisted in his view that he had done nothing wrong.[79] In 1911 he approached the prime minister, H. H. Asquith, asking for a free pardon, and when asked why he deserved it, told Asquith, "Well, the official reason is that I have been a good citizen, for ten years since the offence, and that my conduct is free from any reproach; but if you ask me for the real reason I should say because the conviction was a piece of hypocritical tosh."[81] A free pardon was duly issued by the home secretary, Winston Churchill.[79]

Second marriage

Released from prison, Russell attempted to use his place in the House of Lords to reform the law of divorce. In 1902 he introduced legislation to allow divorce based on cruelty, lunacy, three years separation, or one year if both parties consented. Their lordships, led by Lord Halsbury, immediately voted down the bill, rather than (as was usual with bills that were not to be passed) postponing consideration of it. Russell tried again in 1903, with an identical outcome. Attempts in 1905 and 1908 were treated more gently by the Lords, which postponed consideration rather than rejecting them outright.[82] Russell wrote of his proposals in his second book, Divorce (1912), and a royal commission that year recommended reforms, which were in fact slow in coming: it was not until after the First World War that divorce came within reach of those not wealthy, by allowing petitions to be heard at local assizes rather than in London, and no-fault divorce was not enacted until 1969.[83]

Both because he had become interested in law and because he was in need of income, in 1899 Russell was admitted to Gray's Inn as a student for the Bar. His studies were interrupted by his time in Nevada and in Holloway, but no action was taken against him for his conviction of felony. He was called to the Bar in 1905, and practised for about five years.[84][85]

Russell was an early motorist and an active member of the RAC (then the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Northern Ireland). He was an outspoken defender of motorists' rights. He is famed for having the registration A 1. This is frequently reported as being the first number plate issued in Britain, but was most likely not – it was, however, the first registration issued by the London County Council (LCC), in 1903.[86] Russell was still a member of the LCC, and awarded the registration to himself. The number plate made him a target for the police, and after five speeding tickets and threats to suspend his licence from magistrates, he sold car and plate in 1906. He continued working for motorists' rights as a barrister, taking large numbers of briefs for motoring offences.[87]

The marriage with Mollie was generally a success in its early years; according to Russell's biographer, Ruth Derham, she "genuinely loved him, understood that he must be master in his own house... her outside interests provided them both with a degree of independence."[88] High among these was women's suffrage: both spouses spoke at public meetings in favour of votes for women, and Mollie challenged Asquith to provide more than just a "vague promise" of the vote.[89] Russell disapproved of militant suffragists such as Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, but conceded that their tactics were effective.[90]

Third marriage; First World War years

In 1909 Russell met the woman who would become his third wife, the novelist Elizabeth von Arnim (née Mary Annette Beauchamp), widow of Count Henning August von Arnim-Schlagenthin, by whom she had five children. The widowed von Arnim had an affair with H. G. Wells, and ended her relationship with Wells after learning that he had another lover. At the same time, Frank and Mollie Russell had quarrelled and were growing apart, and he and Elizabeth von Arnim moved in the same literary circles. They fell in love in a visit he paid her, without Mollie, over the New Year of 1914.[91] Mollie Russell petitioned for restoration of conjugal rights but once convinced Frank would not return, accepted an allowance for life, which Bertrand continued to pay after Frank's death in 1931, permitting her to live a life of leisure. In exchange, she sued for divorce on the grounds of desertion and adultery, and the suit was not contested.[92]

Frank and Elizabeth Russell married on 11 February 1916.[93] The marriage failed quickly and acrimoniously, and she fled for America after only six months of marriage, Frank's temper being a major factor. Like each of Frank Russell's marriages, there were no children born of it. It has been suggested that the earl was addicted to cocaine, though Derham found this to be unlikely and contended that the addiction which helped destroy the marriage was Frank's love of gambling at bridge.[94] Two weeks before his death in 1931 Frank Russell wrote to Santayana that he had received two great shocks in his life, when Jowett sent him down from Oxford, and "when Elizabeth left me I went completely dead and have never come alive again."[95] An attempted reconciliation failed in 1919.[93] They never divorced. Von Arnim famously caricatured Russell in her 1921 novel Vera, a depiction that greatly angered him, and when Elizabeth heard of her husband's death in 1931 she said she was "never happier in her life".[96]

Russell had continued to take liberal stances in the House of Lords, strongly supporting the Parliament Act 1911, which diminished its powers, and in December 1912 joined the Fabian Society, the first peer to do so. Nevertheless, he did not align himself with the fledgling Labour Party, and in January 1913, decried the "dangerous immunity" of trade unions.[97] Russell supported British involvement in the First World War once it started, but sympathised with his brother Bertrand's anti-war views. Both opposed conscription, and Frank was one of only two peers to speak in opposition in the Lords when Asquith brought in conscription in 1916.[97]

Bertrand's anti-war activities were considerable, despite Frank urging caution on him; he was successfully prosecuted under the Defence of the Realm Act, banned from areas of the country, sacked from his position as lecturer at Trinity College, Cambridge, and denied a passport to go to America to take up a position at Harvard.[98] By late 1917, though, Bertrand had become disillusioned with his cause and Frank met with General George Cockerill of the War Office, resulting in agreement within the government on 17 January 1918 that the banning order should be lifted. The same day, though, Bertrand published an article, "The German Peace Offer" in The Tribunal, causing the government to rescind the agreement, and in February he was prosecuted and sentenced to six months in prison, a sentence he began in May after an appeal failed. He was allowed, though, to serve his sentence at Brixton Prison, with greater privileges than the magistrate would have given him. In a 1959 BBC interview Bertrand attributed this to Frank's influence over the home secretary, Sir George Cave, though Bertrand's biographer, Ray Monk, believed that Bertrand was confusing the efforts to get him these privileges with Frank's later efforts to secure a remission,[99] which bore fruit when Bertrand was released six weeks early.[100] While Bertrand was in prison, Frank visited him, and with Bertrand limited to one outgoing letter per week, received lengthy letters from his brother containing messages to be given to other people.[101]

Labour politician and death (1921–1931)

Elizabeth's publication of Vera led to threats from Russell's solicitor, but only served to increase interest in the book.[102] Bertrand and Santayana considered the depiction cruel but Santayana admitted it was accurate in detail. The earl carried a copy of it around with him, and attempted to refute individual passages from it to those willing to listen.[103] Russell's more substantial response was to write his memoirs, My Life and Adventures, published in 1923, in which Elizabeth is never mentioned. The book was well received; most reviewers deemed it entertaining.[104]

From the early 1920s Russell was more commonly seen in the House of Lords. He fully embraced the Labour Party when it took office for the first time under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924.[105] He was given no office in that short-lived government, possibly because of his past marital problems.[106] By the time Labour was in government again, in 1929, Russell had proved his worth to the Labour Party both in debate – there were then very few Labour peers – and through service in committee and on royal commissions. Russell hoped to be Lord President of the Council or Leader of the House of Lords, but these posts went to Lord Parmoor. Russell was made Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Transport, Herbert Morrison, a post for which his considerable experience with automobiles qualified him.[107]

Russell's main accomplishment in the Transport position was steering the Road Traffic Act 1930 through the House of Lords. This abolished the 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) speed limit that had been in place for motor cars since 1893, but also required compulsory insurance and set a minimum driving age, as well as legislating against dangerous driving.[108] Having served on the Royal Commission on Lunacy, Russell introduced what became the Mental Treatment Act 1930, allowing voluntary admission to psychiatric facilities and permitting a local authority to establish mental health outpatient clinics.[109]

Russell was promoted to Under-Secretary of State for India under William Wedgwood Benn. He began his tenure by stating that Indian independence was "at this moment impossible", something which although quickly retracted, Nehru concluded was the true attitude of the British government. He worked hard to overcome the gaffe, and was a delegate to the First Round Table Conference (1930–1931). As one of Labour's few representatives in the Lords, he was often called upon to steer legislation having nothing to do with his portfolio. In February 1931, he took a holiday on the Riviera, where he suffered from influenza. Still recovering from this, he died at his hotel in Marseilles on 3 March 1931, the day before he was supposed to depart for home. He was cremated there, and his ashes were scattered in the gardens of his former home, Telegraph House.[110]

The prime minister, MacDonald, stated, "He was one of the most charming men I have ever met and behind his charm of manner was a really very great intelligence. He was a most valuable colleague both in making preparations for the round-table conference and in helping us to study and master the problems involved, and then in making the conference a success."[111] Benn regretted Russell's death "not only because it deprives the India office of a distinguished political figure but because of the personal loss of a brilliant, kindly friend".[111]

Assessment

Russell stated of himself:

I have always been a fighter from the time when I fought first my Uncle Rollo, then Benjamin Jowett, and then for six awful years Mabel Edith. It is my misfortune and not my fault that practically the whole of my life has been chronicled in detail in the daily Press. Few people can abhor and resent publicity in what has to do with the private life more than I do, and the result, of course, is to give the public a curiously distorted view of one's character and tastes.[112]

Annabel Jackson remembered Russell as a child as Bertrand's "beautiful and gifted elder brother".[113] Santayana wrote that while Lionel Johnson could be judged by his poems, "poor Russell had only his ruins to display and to be judged by most unjustly, ruins of passions that had hounded him through life like a series of nightmares, and had made the gossips call him 'The Wicked Earl'."[114] To Derham, Russell "was not a evil man. Neither by modern standards was he 'wicked'. Throughout his life, his strong identification with his youthful self, misunderstood, persecuted, and wronged, led him to seek reforms that benefited many an underdog, but also made him 'suspect the satisfied', 'distrust the majority', impatient with acquaintance and unsuccessful in love."[115] Ann Holmes, in her chapter on the Russell divorce cases, stated that in late Victorian England, "marital fidelity was not as important as the appearance of a stable marriage and happy home; scandal was more shameful than adultery. It was a rule painfully learned by the second Earl Russell and his wife... Russell was a martyr in that he chose to defend himself publicly when he could have addressed his marital problems in private. At the very least, he could have agreed to negotiate a monetary settlement... He and his family paid a high price for his stubborn refusal to relent."[116]

The divorce suits between Frank and Mabel Russell had historic significance.[117] Jack Harpster in his article on Russell's Nevada divorce, noted, "John Francis Stanley Russell's personal problems found expression in political activism, specifically in his effort to change England's outdated divorce statutes. Although he saw no progress during his lifetime..."[118] Gail Savage, in her journal article on Russell's divorce law advocacy, stated, "Frank Russell's vulnerability to the charms of a pretty widow and her pretty daughter had devastating consequences for his personal life. But the trajectory of Frank Russell's personal misfortunes and the impetus of his personality intersected a larger-scale social and cultural dynamic that involved a refiguring of the ways in which we understand gender relations and marriage."[119] The House of Lords' decision in Russell v. Russell remained a leading case in divorce law for decades, establishing several legal precedents.[120] The first celebrity to get a Nevada divorce,[121] Russell's efforts there first drew attention to that state as a place where one could get an easier divorce than at home, though the divorce of Laura and William E. Corey (1906) and the establishment of an office in Nevada (1907) and subsequent promotion of the state by the New York lawyer, William H. Schnitzer, were greater factors in making Nevada a centre for divorces.[84]

Peter Bartrip concluded his biographical sketch of Russell,

It is hard to warm to Frank but easier to excuse, or at least explain, his character in terms of genetic inheritance, peculiar upbringing and the childhood tragedies that cost him most of his immediate family. The adult who emerged was a mass of contradiction: the socialist aristocrat who was proud of his status yet contemptuous of social convention; the agnostic who wrote sermons; the protector of the oppressed who tyrannized servants; the champion of women's rights who bullied his wives; the opponent of bad driving who briefly made a career of defending bad drivers. In the end he will be remembered less for his achievements and more for his marital history, scandals and association with those family members, notably his grandfather, brother and third wife, whose achievements far outshone his own.[122]

Publications

- Lay Sermons (1902)

- Divorce (1912)

- Some Winchester Letters of Lionel Johnson (1919)

- My Life and Adventures (1923)

Notes

References

- ^ "No. 22534". The London Gazette. 30 July 1861. p. 3193.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 102.

- ^ a b Bartrip 2012, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Monk 1996, p. 7.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Monk 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Monk 1996, p. 15.

- ^ Monk 1996, p. 16.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 44.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 34.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 38.

- ^ a b Bartrip 2012, p. 105.

- ^ a b Derham 2021, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Monk 1996, p. 18.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 48.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 49.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Monk 1996, p. 24.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 25, 48.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 89.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 62.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 66.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 104.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 72–76.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 107.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Derham 2017, p. 274.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Derham 2017, p. 275.

- ^ Santayana 1945, p. 44.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 98–102.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, pp. 108–109.

- ^ "East Holme". The Dorset Historic Churches Trust. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 109.

- ^ Santayana 1945, p. 72.

- ^ a b Bartrip 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Santayana 1945, p. 73.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 147.

- ^ a b Bartrip 2012, p. 111.

- ^ Holmes 1999, p. 149.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 191–194.

- ^ Derham 2017, p. 282.

- ^ Derham 2017, p. 283.

- ^ Holmes 1999, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 285.

- ^ Harpster 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 290.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 291–293.

- ^ Watson 2003, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Harpster 2014, p. 9.

- ^ a b Holmes 1999, p. 157.

- ^ Holmes 1999, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 296–302.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 115.

- ^ a b Holmes 1999, p. 159.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 283.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 305.

- ^ Lovell 1949, p. 81.

- ^ Anson 1908, p. 274.

- ^ a b c Derham 2021, p. 308.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 311.

- ^ Lovell 1949, p. 79.

- ^ House of Lords 1901, p. 287.

- ^ a b c "Earl Russell Convicted". The New York Times. 19 July 1901. p. 5.

- ^ Anson 1908, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Anson 1909, p. 216 n.1.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 315.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 286.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 316–318.

- ^ a b c Bartrip 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 319.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 319.

- ^ Savage 1996, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 333–335.

- ^ a b Bartrip 2012, p. 119.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 300.

- ^ Newall, Les (September 1995). "A 1 – Britain's First Registration". "1903 and All That" Newsletter (61). Registration Numbers Club: 8.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 339–341.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 344.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 344–346.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 349–358.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Bartrip 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 318–320.

- ^ Derham 2017, p. 271.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Derham 2021, pp. 371–373.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 383–384.

- ^ Monk 1996, pp. 521–524.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 386.

- ^ Monk 1996, p. 526.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 392.

- ^ Savage 1996, p. 81.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 398.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 121.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 401–403.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 122.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 404–405.

- ^ Derham 2021, pp. 405–408.

- ^ a b "Earl Russell Dies: British Statesman" (PDF). The New York Times. 5 March 1931. p. 5.

- ^ Russell 1923, p. 345.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 124.

- ^ Santayana 1945, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Derham 2021, p. 412.

- ^ Holmes 1999, pp. 140, 160.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 118.

- ^ Harpster 2014, p. 10.

- ^ Savage 1996, p. 84.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, pp. 218–219.

- ^ "The Rich and Famous". Reno Divorce History. Special Collections, University of Nevada-Reno Libraries. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ Bartrip 2012, p. 126.

Sources

- Anson, Sir William R. (1908). The Law and Custom of the Constitution (Third ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Anson, Sir William R. (1909). The Law and Custom of the Constitution (Fourth ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Bartrip, Peter (Winter 2012). "A Talent to Alienate: The 2nd Earl (Frank) Russell (1865–1931)". Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. 32 (2): 101–126. doi:10.15173/russell.v32i2.2229. S2CID 144279567.

- Derham, Ruth (Winter 2017). "'A Very Improper Friend': the influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell". Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. 37 (2): 271–286. doi:10.15173/russell.v37i2.3415. S2CID 149144448.

- Derham, Ruth (2021). Bertrand's Brother: The Marriages, Morals and Misdemeanours of Frank, 2nd Earl Russell. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-3981-0284-2.

- Harpster, Jack (Summer 2014). "The Strange but True Story of the Nobleman, the Cobbler's Daughter, and the Scandal over an Early Nevada Divorce" (PDF). Nevada in the West: 8–10.

- Holmes, Ann Sumner (1999). "'Don't Frighten the Horses': the Russell Divorce Case". In Robb, George; Erber, Nancy (eds.). Disorder in the Court: Trials and Sexual Conflict at the Turn of the Century. London: Macmillan. pp. 140–163. ISBN 978-1-349-40573-2.

- House of Lords (1901). Journals of the House of Lords. Vol. 133. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

- Lovell, Colin Rhys (October 1949). "The Trial of Peers in Great Britain". The American Historical Review. 55 (1): 69–81. doi:10.2307/1841088. JSTOR 1841088.

- Monk, Ray (1996). Bertrand Russell: the Spirit of Solitude, 1872–1921. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-82802-2.

- Russell, Earl (1923). My Life and Adventures. London: Cassell & Co.

- Santayana, George (1945). The Middle Span. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Savage, Gail (Summer 1996). ""... Equality From the Masculine Point of View ...": The 2nd Earl Russell and Divorce Law Reform in England". Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. 16 (1): 67–84. doi:10.15173/russell.v16i1.1893. S2CID 142446950.

- Watson, Ian (Summer 2003). "Mollie, Countess Russell" (PDF). Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. 23 (1): 65–68. doi:10.15173/russell.v23i1.2039. S2CID 169378393.

Further reading

- Anonymous. "Russell's parents and grandparents". Archived from the original on 2007-08-19. This university website has portraits of the 2nd Earl Russell and describes him as "already quite uncontrollable, as later demonstrated by his marital and financial turbulence" when he came to live with his grandparents.

- Derham, Ruth (2021). "Frank Russell's Diverse Writing and Speaking Career: A Bibliographical Guide". Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. 41: 62–76. doi:10.1353/rss.2021.0005.

- Derham, Ruth (2020). "Bible Studies: Frank Russell and the Book of Books". Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. 40: 43–51.

- Derham, Ruth (2018). "Ideal Sympathy: The Unlikely Friendship of George Santayana and Frank, 2nd Earl Russell". Overheard in Seville. 36: 12–25. doi:10.5840/santayana201836363.

- Furneaux, Rupert (1959). Tried by their Peers. London: Cassell. Two chapters are devoted to trials for bigamy, that of Elizabeth Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston, and that of the 2nd Earl Russell.

External links

- 1865 births

- 1931 deaths

- Bertrand Russell

- British people convicted of bigamy

- British politicians convicted of crimes

- Earls Russell

- Labour Party (UK) hereditary peers

- Members of Gray's Inn

- Members of London County Council

- Nevada culture

- Progressive Party (London) politicians

- Recipients of British royal pardons

- Russell family