Talk:Alcoholism

| This is the talk page for discussing improvements to the Alcoholism article. This is not a forum for general discussion of the article's subject. |

Article policies

|

| Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| Archives: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

| Alcoholism received a peer review by Wikipedia editors, which is now archived. It may contain ideas you can use to improve this article. |

Archives |

|---|

Forms of Alcoholism

This article is about Alcoholism. Discussions regarding the Disease Theory of Alcoholism have been moved to their own page, so please discuss that topic on that page, and we will summarize the results in this article.

This article has special considerations because a thorough examination of the available information on alcoholism indicates that there are at least two forms of alcoholism with no professional differentiation between them. Those who study one of them tend to insist that their form is the one and only true alcoholism, and this has resulted in a great deal of professional disagreement. The following few paragraphs are a description of these two forms based on research performed while writing this article. This should not be considered authoritative, and cannot go into the main article due to "original research" limitations, but I am presenting it here as a guide for those who wish to contribute to the article, to help them understand the considerations that have gone into it.

The first is the psychological/social addiction which comes about during a period of a person's life when alcohol consumption is of significant benefit to a person. This period may be a one time thing (like during college or after a divorce), or it may be a recurring thing (like that semi-annual girls night out or company party). This perception of benefit is often carried over for a considerable time after the benefit ceases to exist. This form of alcoholism can run rampant across the person's life until others help them realize that alcohol isn't providing benefit to match the problems it's causing.

The second form of alcoholism is a physiological condition in which the person's endorphin system convinces them that drinking alcohol is beneficial to them. It is essentially identical to a morphine or heroin addiction (endorphin being "endogenous morphine"), but is triggered by the consumption of alcohol (which releases endorphins into our system), and therefore alcohol consumption is the behavior that it reinforces. This form of alcoholism completely defies logic and sensibility, and often requires severely traumatic consequences to occur before the alcoholic is willing to admit that they have a problem. Even then they are often unable to quit drinking without assistance.

This results in several misperceptions of alcoholism. The most damaging one is due to differences in endorphin production and reception. Only about one sixth of the population is susceptible to the second form of alcoholism. This means that the majority of people who have suffered from the first type don't understand why the second type can't just quit.

In any case, the word Alcoholism does apply to both forms without differentiation, and therefore you will notice a few compromises in this article which are designed to reflect that unofficial duality.

Robert Rapplean 21:53, 28 September 2006 (UTC)

genetic testing

At least one genetic test[3] exists for a predisposition to alcoholism and opiate addiction. Human dopamine receptor genes have a detectable variation referred to as the DRD2 TaqI polymporphism. Those who possess the A1 allele variation of this polymorphism have a small but significant predisposition towards addiction to opiates and endorphin releasing drugs like alcohol[4]. Although this allele is more common in alcoholics and opiate addicts, it is by itself inadequate to explain the full effect of, or be a reliable predictor of alcoholism.

Which would it be, the small yet significant predisposition, or inadequate to explain/be a predictor to alcoholism? If it isn't significant, the word significant could be removed and it'd be fine. If it is, I'd say how that plays into its role as an indentifier but not a predictor. The wording is just a little ambigious here (one of those wtf moments). JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 15:51, 29 September 2006 (UTC)

- I think it's a usage issue. Maybe "small but statistically significant" is the proper phrase. It doesn't explain, predict, or identify an alcoholic. A person with this allele may be able to drink alcohol with no addictive results. However, this allele is slightly more common in those who have shown addiction to alcohol than in those who have shown the lack of this behavior. This suggests that, if all other things are equal the existence of the allele encourages people towards alcoholism, but that there are other factors and/or alleles that have a much stronger effect. Would you care to suggest an alternate phrasing that states this better? Robert Rapplean 19:07, 1 October 2006 (UTC)

- i find this a little less cloudy:

At least one genetic test[3] exists for an allele that is correlated to alcoholism and opiate addiction. Human dopamine receptor genes have a detectable variation referred to as the DRD2 TaqI polymporphism. Those who possess the A1 allele variation of this polymorphism have a small but significant tendancy towards addiction to opiates and endorphin releasing drugs like alcohol[4]. Although this allele is slightly more common in alcoholics and opiate addicts, it is not by itself an adequate predictor of alcoholism.

- I added the words 'correlated' and 'tendancy' so that the word 'predisposition' isn't used, as later it is stated it isn't an adequate 'predictor'. hope that clears things up. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 23:41, 1 October 2006 (UTC)

screening

i think that the screening section either should be the CAGE questionnaire and one more example, or they all need to be flushed out in more detail. right now it looks like a bunch of edits people crammed together. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 16:08, 29 September 2006 (UTC)

P.S. The DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence represents another approach to the definition of alcoholism, one more closely based on specifics than the 1992 committee definition. - wtf is the 1992 committee definition? not mentioned anywhere else. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 16:11, 29 September 2006 (UTC)

- You've done a very good job of fleshing this out. I think at this point we might want to resort to listing them (like in the terminology section) and making sure we provide them with equal coverage.

- The 1992 committee definition refers to something that was pulled out or moved away. Such statements that compare themselves favorably to other statements in the article were fairly common when we had many people contending for dominance on this article, and I haven't fully removed them all yet. This statement should be made to be more self-contained. Robert Rapplean 19:07, 1 October 2006 (UTC)

- Done, done. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 23:29, 1 October 2006 (UTC)

- The standard definition for alcoholism in the medical field is the 1992 committee definition that was here when that paragraph was written. The article, "The Definition of Alcoholism," was published in JAMA on 8/26/92 (Vol 268, #8, p1012) and was the result of work by the Joint Committee of the National Council on Alcoholism and the American Society of Addiction Medicine. The entire definition was part of this article originally and probably should be again: "Alcoholism is a primary, chronic disease with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. The disease is often progressive and fatal. It is characterized by impaired control over drinking, preoccupation with the drug alcohol, use of alcohol despite adverse consequences, and distortions of thinking, most notably denial. Each of these symptoms may be continuous or periodic." The article goes on to define each term within the definition to a greater extent. For the past 14 years, this definition has been accepted by the medical community and provides the descriptive basis upon which physicians treat addictive disease, alcoholism in particular. Drgitlow 00:58, 18 October 2006 (UTC)

Ah, right. That was part of the introduction that we had such extensive disagreement about. For those who are new to this, you can find much of that argument in Archive 3. The short version is that a lot of it was replaced because it used categorizations that are not comprehensible to the average reader. It also resulted in the moving of the disease discussion to its own page. Robert Rapplean 17:04, 18 October 2006 (UTC)

I would like to suggest the addition of Internet-based alcohol screening resources available as a public service, as they can be very useful. One such resource is AlcoholScreening.org, devleoped by Boston University School of Public Health (full disclosure: I helped develop this website). This site provides screening results based on the AUDIT and U.S. Dietary guidelines for alcohol consumption. There is at least one such site in the United Kingdom based on its health service guidelines, one in Australia, and so on. There are a few such commercial services as well, although I am initially inclined to list only those Internet public service (free) screening sites which are sponsored by a credible source, i.e. a University, qualified health facility, or a governmental health agency. These tools do not exclusively screen for alcohol dependence (alcoholism) but also cover hazardously excessive consumption that may cause future problems or put one at risk for immediate consequences such as accidents. The best ones are nonjudgemental and non-labeling. I am quite willing to contribute this content, but I would appreciate guidance on where and how to do so. Should this be a new item under Screening? Should it go at the end under "see also?" Other suggestions? Eric Helmuth 02:39, 15 November 2006 (UTC)

- Hello and welcome, Eric. I looked through the screening on alcoholscreening.org and think that it's at least as valid as any other screening I've seen, and would be useful for people to confidentially understand how much of a problem their drinking is from an objective perspective. My view would be to just drop the content at the end of the Screening section, with an introductory sentence something like "Many free screening resources exist online...". It will likely be mulled over after that and may be reformatted. I'm not currently very happy with the "list quality" of that section, and would prefer a short paragraph describing the advantages and disadvantages of each screening type, but feel it's important enough to know that online confidential screening exists for this inclusion. Other opinions? Robert Rapplean 19:03, 15 November 2006 (UTC)

- Thanks for the warm welcome, Robert. I can't make the edit right now due to the protected status of the page, so others should feel free to add it if desired; otherwise I'll wait until my account clears. - Eric --WikkiTikkiTavi 02:18, 17 November 2006 (UTC)

- I'm now able to edit and have added some minimal information as suggested. Sugggestions for expansion and improvement are welcome. Eric Helmuth

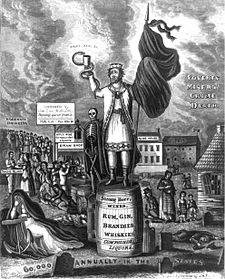

images

i found these two images over in the wikimedia commons [1]:

...and this article could use a little imagery. the top was given from a german contributor, and the bottom from an icelandic (here is a site for its explaination, hope someone speaks the language [2]). either way, i hate to see an article go without images but i also don't know the context of these two pictures too well as they are in a foriegn tounge. anyone game to try and incorporate one or both? JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 20:43, 29 September 2006 (UTC)

- I agree strongly that the article needs images. Where would you put these and to illustrate what?--Twintone 21:03, 29 September 2006 (UTC)

- There in lies the problem; a simple sentence about the era these images are from in the description of the thumb would do, but both sources are in languages other than english. Anyone know someone who speaks German or Icelandic? Actually, thats a dumb question, i'll look around the Babel categories, unless someone beats me to it. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 22:19, 29 September 2006 (UTC)

- I'm going out for the night, but in case anyone wants to beat me to it before tomorrow, here ya go [3]! :) JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 00:49, 30 September 2006 (UTC)

- Look what I foooooound: [4]. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 18:39, 30 September 2006 (UTC)

- I'm going out for the night, but in case anyone wants to beat me to it before tomorrow, here ya go [3]! :) JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 00:49, 30 September 2006 (UTC)

- There in lies the problem; a simple sentence about the era these images are from in the description of the thumb would do, but both sources are in languages other than english. Anyone know someone who speaks German or Icelandic? Actually, thats a dumb question, i'll look around the Babel categories, unless someone beats me to it. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 22:19, 29 September 2006 (UTC)

I tracked down the original and recropped it to get a bigger picture out of it. I've added it to the article. Here it is:

JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 18:59, 30 September 2006 (UTC)

I like where you put that one, it makes a good opening. I think someone took offense to the images that were in here a while ago, because there used to be many more. I'd really like to see more informational images (like statistical charts or whatnot) because most of the "alcoholism" images tend to be ominous pro-prohibition woodcuts and whatnot, and too much of that can be very offputting to readers. I'll keep an eye out. Robert Rapplean 19:13, 1 October 2006 (UTC)

- Tah-rue. Some info graphs on statistics would be excellent. I'll see what I can do too. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 23:16, 1 October 2006 (UTC)

Rationing section

Some programs attempt to help problem drinkers before they become dependents. These programs focus on harm reduction and reducing alcohol intake as opposed to abstinence-based approaches. Since one of the effects of alcohol is to reduce a person's judgement faculties, each drink makes it more difficult to decide that the next drink is a bad idea. As a result, rationing or other attempts to control use are increasingly ineffective if pathological attachment to the drug develops.

Nonetheless, this form of treatment is initially effective for some people, and it may avoid the physical, financial, and social costs that other treatments result in, particularly in the early phase of recovery. Professional help can be sought for this form of treatment from programs such as Moderation Management.

This section to me seems like a long-winded way of saying there are harm-reduction programs (i.e. non-zero-tolerance approaches). This is mentioned in the Treatments section that is short but done pithily. Anyone object to me removing this section? JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 16:47, 2 October 2006 (UTC)

- 'Fraid so. Rationing is a viable treatment option that is significantly different from the others mentioned. This section provides a good overview of it, as it describes the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. However, We should seriously consider combining that with the "return to normal drinking" section, since they are functionally identical. Robert Rapplean 17:42, 2 October 2006 (UTC)

This section currently says "While most alcoholics are unable to limit their drinking in this way". Is it really most? Or some? Do we need a citation here? -Brian

- Hi, Brian. In reality, the argument tends to be whether the word should be "most" or "all." There's a plethora of evidence that suggests that moderation makes alcoholism worse for most people, and yet there are those for which it works. Some argue that those who can deal with their alcoholism with moderation aren't really alcoholics, but are just people who enjoy alcohol. Even Moderation Management, which leads the call for this form of treatment, insists that their members aren't alcoholics. We actually used to have a citation in here ( Pendery et al. Controlled drinking by alcoholics? New findings and a reevaluation of a major affirmative study. Science 1982 Jul 9;217 (4555):169-75) ) that states this, but I wouldn't want to further clutter the article by include it in that statement unless the consensus was that this statement was controversial.

- So what do we think? Is the statement "most alcoholics are unable to benefit from moderation" controversial? Robert Rapplean 22:23, 22 January 2007 (UTC)

- The question comes down to whether an "alcoholic" is anyone who abuses alcohol, or strictly someone with a physical dependence on alcohol. We should avoid the term "alcoholic" and refer directly to the meaning in context, such as "most abusers of alcohol" or "all sufferers of alcohol dependence". --Elplatt 22:36, 22 January 2007 (UTC)

- Um, neither. An alcoholic is someone who has extreme difficulty with not drinking, even when it's obviously harmful. People abuse alcohol all the time for perfectly valid social reasons. If it'll allow you to interact socially, or catch they eye of the girl you like, then it sometimes seems like a really good idea to drink until you're passed out in the bushes. Also, physical dependence suggests alcoholism, but it isn't the disease of alcoholism any more than a bunch of red spots are the disease of measles. It's just an effect that the disease causes.

- In this context, moderation would actually be a good idea for someone who just drinks too much and/or is physically dependent. It would back off of the physical dependence with less damage than detox, and would entirely eliminate excessive drinking. For an alcoholic, though, it increases the urge to drink and results in heavier drinking. -- Robert Rapplean 21:39, 1 February 2007 (UTC)

- "someone who has extreme difficulty with not drinking, even when it's obviously harmful" is the definition of abuse. This may be your definition of alcoholism, but some people use other definitions. Whenever possible, we should avoid using the ambiguous term "alcoholism" because things that are true for one definition may not be true for another. --Elplatt 23:37, 1 February 2007 (UTC)

- Please read the terminology section of this article, which has been hashed over rather thoroughly, before continuing this argument. I am more than a little aghast at your suggestion that we should avoid using the term "alcoholism" in the article about alcoholism. - Robert Rapplean 02:45, 2 February 2007 (UTC)

- I've read the terminology section. Abuse has a precise medical meaning (as I said). The term "alcoholism" is only defined in the intro, and that definition differs from the one used in many scientific papers. I can see how someone would disagree with the suggestion to avoid using the term "alcoholism" but if you are aghast, you should give the topic more thought. Since this subject is only tangentially related to rationing, I'll start a new subheading. --Elplatt 05:02, 2 February 2007 (UTC)

- Wikipedia is not a medical text. This is a good thing because the medical community is full of conflicting statements that are absolutely certain that their definition of alcoholism is the One True Definition(tm). As it currently stands, this article has suffered the ravages of a physician, a psychiatrist, a neurobiologist, and several AA enthusiasts all simultaneously insisting that their X++ years of education state that alcoholism must be this one thing. At times it's been extremely frustrating.

- Wikipedia attempts to reflect common usage, which includes how people in the non-medical community talk about alcoholism. The definition presented at the beginning of the article is a meticulously gathered consensus based on evidence presented from many perspectives that make use of the word, and represents the operational definition of alcoholism to be presumed throughout the article. Anything else would be nihilism. If you feel that this definition is in error, please review the conversations stored in the archives to identify which specific elements you feel were not adequately explored and present new evidence about them.

- In reference to this specific statement, regardless of the definition of alcoholism, we can UNCONDITIONALLY state that those who suffer from alcoholism are called "alcoholics". While it is, of course, bad style to use alcoholism in a self-referential way in the article (e.g., alcoholism is the problem that alcoholics have), providing characteristics of alcoholics is a fully qualified method of describing the characteristics of alcoholism itself. Therefore it is ludicrous to suggest that we should avoid making statements like "alcoholism is..." and "alcoholics are..." in an article about alcoholism. Robert Rapplean 20:33, 2 February 2007 (UTC)

- Stepping in here kind of late, MM's position in regards to rationing approaches is somewhat similar to this: If you are currently drinking, and can successfully use their approach to reduce the *harm* that drinking is doing to your life, it might be worth a shot to try MM. However, if you've been abstinent for a number of years, what is most likely to happen at an MM meeting is people congratulating you on your weekly "ration" of zero drinks, and encouraging you to keep at that level. Even Moderation Management, which leads the call for this form of treatment, insists that their members aren't alcoholics. is a tad misleading, as the general MM party line is that if someone *is* totally unable to modify their behavior, they aren't ready for MM approaches yet, as they simply cannot successfully ration their drinking behavior at all (by definition). In addition, the general MM media stance is that if somebody *is* a self-defined AA "alcoholic" (as compared to a peer defined), MM is not an easy excuse to start drinking again, and MM is probably not a choice that they should exercise. Summarized even further, If you truly match step one of the twelve steps, MM simply will not work. Ronabop 05:38, 28 February 2007 (UTC)

Detoxification Section

FYI, I feel that it's important to emphisize that detox is not a treatment for alcoholism, but a method for reversing the metabolic imbalance caused by regular alcohol use. It does nothing at all to curb the desire to drink. I'm ok with this statement being dropped to the third paragraph, though. Robert Rapplean 18:15, 2 October 2006 (UTC)

Naltrexone

There are currently two ways that naltrexone is used, and the two are strongly in contention. Naltrexone was ok'd by the FDA for use for alcoholism in 1995.

The FDA site suggests that people not drink when taking naltrexone. It is generally prescribed to alcoholics as a way of helping them maintain abstinance, for which it has a very small effect for some people. There is a great deal of research (see above) that suggests that, on the average, naltrexone has questionable value in maintaining abstinance. As a result most doctors will do one of three things: provide naltrexone with the instructions to avoid drinking, cocktail naltrexone with antabuse to specifically discourage drinking, or avoid naltrexone whatsoever.

Pharmacological extinction specifically requires the alcoholic to drink while on naltrexone, preferably where and when they normally drink. The FDA's standard instructions specifically prevent PE from occuring, and coctailing it with antabuse is even worse. PE has a success rate of about 87% for converting serious alcoholics into people who can forget alcohol exists from one day to the next, and have no problem with drinking socially.

Unfortunately, most people think that the drug IS the treatment, and as such the two treatments get confused, very much like what you did in your recent edit. This results in most people thinking that the "naltrexone to maintain abstinence" results reflect on the "naltrexone to cause extinction" treatment. It may take extra explaining to maintain the differentiation. Robert Rapplean 18:07, 2 October 2006 (UTC)

'result'

the word 'result' is used 18 times in this article. i'll start to try and get the wording more varied, but please for a while hold off on using that danged word. it gets tiring. :) JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 16:41, 4 October 2006 (UTC)

- it's now down to 4-5. thats better; it really does make it read a lot nicer. i once had a english teacher who told us to write a 8-10 sentence piece about anything that happened the week before. afterwards he told us to count the uses of the verb 'to be'. replacing this verb with any other verb makes it a much more descriptive piece. this article's removal of the word 'result' is something similar. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 17:39, 4 October 2006 (UTC)

sinclair method/Pharmacological extinction

There is a lot of professional resistance to this treatment for two reasons. Pendery et al in 1982[1] demonstrated that controlled drinking by alcoholics was not a useful treatment technique. Many studies have also been done which demonstrate naltrexone to be of questionable value in supporting abstinence.[2][3][4](et. al.) For those who don't understand the mechanism involved, these results have been assumed to demonstrate the ineffectiveness of the two treatments in combination. This logic isn't applicable because it assumes that the two treatments are merely complementary, like two people pushing a car, as opposed to sequential, like turning a doorknob and then pulling on it.

The Finnish study[5] indicated, "Naltrexone was not better than placebo in the supportive groups, but it had a significant effect in the coping groups: 27% of the coping/naltrexone patients had no relapses to heavy drinking throughout the 32 weeks, compared with only 3% of the coping/placebo patients. The authors' data confirm the original finding of the efficacy of naltrexone in conjunction with coping skills therapy. In addition, their data show that detoxification is not required and that targeted medication taken only when craving occurs is effective in maintaining the reduction in heavy drinking."

i'm not sure if this section of the Sinclair Method/Pharmacological extinction is supposed to be a critism aspect or anything, but right now its just a study abstract. the references these studies are connected to might be laced into other places as cites, but i don't think they should be getting 2/3rds of the section - especially as the first is heavily docked for being illogical. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 16:55, 4 October 2006 (UTC)

- The last section can be summed up as "check out the actual studies for proof". It's really too technical for this article, so should be summarized or deleted. I believe it was put in there by a psychiatrist who was editing this article earlier, and was trying to adjust it to appeal better to medical professionals.

- The middle paragraph is necessary because it describes the ongoing mental conflict that causes people to disregard a treatment option of unprecedented effectiveness. I'd appreciate an explanation of why you consider it illogical, because it scans pretty logically to me. Robert Rapplean 21:23, 4 October 2006 (UTC)

I'd be for deleting both unless the middle got a re-write. I called it 'illogical' as the final sentence says This logic isn't applicable because... which pretty much dashes some of the afore mentioned studies to the rocks. At least I think what thats refering too (which you might interpret as what X readers are thinking). Also the phrase For those who don't understand the mechanism involved immediately sets up a position of writer vs. reader, which feels, uh, condescending (i'm here to understand the mechanism involved). It is definitely not encyclopedic style writting.

The first paragraph to this section is great and clear, the 2nd and 3rd are foggy. There should be like one paragraph summarizing studies out there, it doesn't have to get too nitty gritty; thats what the sinclair article fork is for. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 17:02, 5 October 2006 (UTC)

- This being the case, could I enlist your help in rewriting? Let me see if I can clarify what I'm trying to describe. Pharmacological extinction is a little like a [Glossary_of_wildland_fire_terms|backfire]. Setting fire to trees is known to make them burn. I don't need a study to prove that. Blowing air at large fires makes them burn faster. Again, easily provable. Each of these by themselves would only make a wildfire spread more quickly, and again, that's readily demonstrable. However, if you find a place where the wind is burning towards the fire and set fire at that place, the backfire will burn towards the main fire and consume all of the fuel in its path. This doesn't contradict our two starting facts, it just invalidates the idea that you can't combine the two in order to fight fire. Could you help me explain this? Robert Rapplean 22:30, 5 October 2006 (UTC)

- I steer from the complex metaphor just a bit. Here is how i re-wrote it, tell me how you feel:

There is a lot of professional resistance to this treatment for two reasons. Studies have demonstrated that controlled drinking for alcoholics was not a useful treatment technique[21]. Other studies have also shown naltrexone to be of questionable value in supporting abstinence alone.[22][23][24]. The individual failure of these two separate treatments often lends to the idea that their use in combination is equally ineffective. Some assume that the two treatments are complementary, like two people pushing a car; others feel they are effective as they are sequential, like turning a doorknob and then pulling on it.

- maybe throw that Finnish study ref in there as a nail on the coffin (as an inline cite, the last sentence will do as a summary)? JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 05:28, 6 October 2006 (UTC)

I'm good with this, with the exception of others "feeling" that they are effective. Pharmacological extinction makes some pretty bold claims, and I've given it a monumental level of scrutiny, even going so far as to talk on the phone with all of the researchers involved, calling a good dozen treatment agencies, and have a chat with the head of the research department at the NIAAA. The comments about it tend to fall into one of three categories. (a) it's obviously proven to work, (b) studies show naltrexone is a waste of money and letting an alcoholic drink is like trying to put a fire out with gasoline, or (c) I haven't looked at it before, but it sure seems to make sense. I've examined studies out the wazoo (I'll give you a list if you like), and everything done on opiate antagonists and alcoholism either supports it or completely fails to address it. The only room for feeling here is those who don't feel that it's worth their time to look into, which unfortunately is damn near everyone. I think we'd be doing our readers a disservice by making such a weak statment about it. Robert Rapplean 22:02, 6 October 2006 (UTC)

- Hmm, that last sentence still kinda bothers me too. The important thing to remember here is no original research (although it sounds like you've taken the time to be extremely erudite on the subject), and to be NPOV. I think you can explain the con side's shortcomings without making it unbalanced. Take a cut at that last sentence (try removing the metaphor, although good) and try to articulate the point in another way perhaps. UPDATE: Whoop, looks like you're doing that right now. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 22:13, 6 October 2006 (UTC)

- Perhaps saying people presume that the effects are 'additive', where adding together two failure still means failure. However research shows the effects tend to be 'synergetic'; where each fails alone both can succeed together. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 22:17, 6 October 2006 (UTC)

It's a little more complicated than that. Attempting to moderate alcohol use actually enhances the addiction by increasing the endorphin conditioning, although more slowly than for excessive drinking. Similarly, naltrexone all by itself has no notable effect on the actual addiction if you don't drink. It slightly decreases the urge to drink while you're taking it, but there's a rebound effect when you stop taking it and the sum total results in effects slightly worse than if you don't take it at all. Synergy suggests that the two effects are minor on their own, but significant when used together, and that isn't the case. The two are actually negative when used alone.

- I have to disagree with you there, [5]. 'Synergy' the word doesn't mean the two effects alone are minor, just that when the two combine the effect is greater than the sum of their individual effects.

Ok, strike "minor" insert "lesser". Nonetheless, in synergy the effect is only changed in magnitude, not in direction. That is where the difference lies. Robert Rapplean 19:10, 15 October 2006 (UTC)

The door example helps describe this. You turn the knob and pull on it, the door opens towards you. But let's say that the door is hinged to swing both ways, and there's a wind at your back. If you turn the knob without pulling on it under those conditions, the door will open away from you instead of toward you. Similarly if you pull on it without turning the knob you wedge the pin against the side of its hole, making it harder to turn the knob and open the door. Individually, the two efforts have a negative effect on the goal of getting the door to open towards you, but taken sequentially they work with little effort. 198.152.13.67 16:38, 13 October 2006 (UTC)

- the metaphor is fine and good, but doesn't sound encyclopedic and gets kinda like 'wait, what was he talking about again?' towards the end. personally it looses me. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 17:22, 13 October 2006 (UTC)

I can't disagree with you there, but I'm still at a loss for how to describe it in the article in a way that doesn't violate some principle, and yet actually describes it accurately. Robert Rapplean 19:10, 15 October 2006 (UTC)

peer review/copy editing

Originally finding edge into this article via it's Peer Review request, i've finally finished and even done a good deal of copyediting along the way. Some overall comments:

- This article needs forked articles; identification/diagnosis, effects and treatment are all too long & multifacited to not do so. I meant, this article is big, like 30k, and it gets a little tough to stick with the article when it's this daunting. It took me like a week to get through it myself for Peer Review/Copyedit.

- More cites. It isn't usually an NPOV thing, but alcoholism is a very studied condition, and there just isn't any excuse not to have a shit-ton of sources to this baby. Someone might also look around userpages for a substance abuse counselor or something to help with these.

- A lot of the sections seem sort of disconnected; i even caught a few repeats of something that had been said in a previous part of the article. Like a good essay, each needs to lead into each other to make a better flow.

- Stop using that damn word 'result'. ;) Getting 'results' is one thing, but having everything 'the result of this' and 'resulting in that' makes this article seem like a robot.

- As previously mentioned, more diagrams and images would better this article. Also, i know there is a ton of statistics out there, and it'd be great to have this article peppered in them.

Anyways, i've really enjoyed working on this baby, and i'll be around to help it out. JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 17:55, 4 October 2006 (UTC)

- Thanks, Joe. Your input has been a great help. This article tends to get smacked around a lot by POV hacks, and it's good to get unbiased input on the content.

- Glad to help. :)

- BTW, there's a perfectly good excuse for not having a shit-ton of statistics. The majority of these statistics are performed by someone who's trying to prove their personal theory correct, and they often conflicting with other people's statistics. Reconciling those statistics is something that's of very little interest since there's no hard evidence one way or another and no money to be made by it. Because of this, any comparison of statistics has to be done on the fly, and gets labeled "original research". Not neccessarily a good reason, but a pretty damn good excuse. I'll keep working on it.

- Robert Rapplean 21:26, 4 October 2006 (UTC)

- You might put a little bit in about statistics being varied, and perhaps include a range of them a demonstration of such. Again, don't worry about 'original research' interpretations so much. I think you do a great job, be bold and see where it goes. :) JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 17:05, 5 October 2006 (UTC)

Semi-protection?

As this page seems to be a common target for vandals and we're spending half our time just reverting their nonsense, can we get it semi-protected to reduce the rate of vandalism? Nunquam Dormio 18:11, 24 October 2006 (UTC)

I second this request. Who should we talk to about this? It seems that everyone with a bone to pick wants to tell everyone that their personal annoyance is a pathetic drunk, and everyone with an idea to sell to alcoholics wants to hawk it on this page. Robert Rapplean 21:58, 31 October 2006 (UTC)

I support the idea of semi-protecting this page, at least temporarily. There has also been a problem here and on related pages with linkspammming. WP:ANI might be the place to bring it up; I'll take a look around and post a request for Sprotect. --Doc Tropics Message in a bottle 22:01, 31 October 2006 (UTC)

I posted an Sprotect request here --Doc Tropics Message in a bottle 22:13, 31 October 2006 (UTC)

- This is getting silly. The page got vandalized multiple times...while I was requesting protection! --Doc Tropics Message in a bottle 22:50, 31 October 2006 (UTC)

Thanks, Doc. I seconded your request (dunno if that'll help or even matter), and moved it to the top of the sprotect list, where the administrators can find it. Robert Rapplean 22:58, 31 October 2006 (UTC)

- Thanks RR. It was the first time I've filed a request and I automatically put it at the bottom, just like we post on Talkpages. I'm glad you caught that :) --Doc Tropics Message in a bottle 23:06, 31 October 2006 (UTC)

- Many Thanks to Centrx for the Sprotect! --Doc Tropics Message in a bottle 05:18, 1 November 2006 (UTC)

- Seconded! Nunquam Dormio 19:00, 1 November 2006 (UTC)

Adjusting long-term physical health effects

I've had my eye on this section for a while. The article Alcohol consumption and health describes this in great detail, and it really isn't germain to alcoholism so much as extended alcohol consumption. Unless someone has a good reason not to do it, I'd like to shorten it to read as follows:

It is common for a person suffering from alcoholism to drink well after physical health effects start to manifest. The physical health effects associated with alcohol consumtion are described in Alcohol consumption and health, but may include cirrhosis of the liver, pancreatitis, polyneuropathy, alcoholic dementia, heart disease, increased chance of cancer, nutritional deficiencies, sexual dysfunction, and death from many sources.

I'll let this sit for a week before taking the scissors to the article. Robert Rapplean 02:01, 2 November 2006 (UTC)

- A link to the alcohol consumption article is reasonable. The vast majority of those with alcohol intake related physical disease also suffer from alcoholism, but you're right that it's the alcohol intake itself which is the cause, not the alcoholism. Drgitlow 04:42, 4 November 2006 (UTC)

- Hi, sorry I'm coming so late to this discussion (my Watchlist is clogged and this got lost). I think RR's assesment is correct and the suggestion is a good one. As pointed out in the Peer Review, the article is excessively long. Whenever it's possible to streamline a section that can be linked to an independent article, we should certainly consider it. Please note, this is mostly "moral support"; I simply don't feel qualified to make decisions about specific content within those sections. --Doc Tropics Message in a bottle 20:28, 8 November 2006 (UTC)

Now that Alcoholism has settled down a lot since we semi-protected it, could some of the regulars turn their attention to Alcohol consumption and health? Although long, it's incomplete and not very balanced. Nunquam Dormio 18:51, 15 December 2006 (UTC)

genetic predisposition against alcoholism

i recently was leafing through a gigantic substance abuse manual, and found something pretty similar from what i see over at Effects of alcohol on the body article:

Some people, especially those of East Asian descent, have a genetic mutation in their acetaldehyde dehydrogenase gene, resulting in less potent acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. This leads to a buildup of acetaldehyde after alcohol consumption, causing the alcohol flush reaction with hangover-like symptoms such as flushing, nausea, and dizziness. These people are unable to drink much alcohol before feeling sick, and are therefore less susceptible to alcoholism. [6], [7] This adverse reaction can be artificially reproduced by drugs such as disulfiram, which are used to treat chronic alcoholism by inducing an acute sensitivity to alcohol.

i say this info should be injected into this article. what do we say? JoeSmack Talk(p-review!) 06:04, 12 November 2006 (UTC)

I'm inclined to say not. I'm aware of this particular genetic anomoly, and I'm also aware that another side effect is a slightly shorter life expectancy. My thoughts are that, while very interesting, groups who are not effected by alcoholism isn't as germain to the main topic of alcoholism as those who are and why. Also, a genetic anti-predisposition isn't very meaningful to those who are trying to understand the problem. Maybe we can start a branch with this information? Robert Rapplean 19:30, 12 November 2006 (UTC)

- I'm with Rob't on this one. The genetic issue isn't relevant to alcoholism directly, but rather to metabolism of alcohol itself. It therefore would fit nicely into the alcohol article (if it isn't already there). I'm not familiar with any studies, however, demonstrating a relationship between this genetic condition and alcoholism. One might speculate, as the person making the statement above did, that individuals with this gene are less susceptible to alcoholism. I suspect that's not the case, however, and would want to see cited studies supporting such a claim before making such a suggestion. Drgitlow 22:33, 29 November 2006 (UTC)

Blossoming list of detox drugs

This is largely addressed to Dr. Gitlow because of his contributions of information regarding barbituates' value in the detox process. It's also addressed to PointlessForest, whose addition looks an aweful lot like an advertisement. Because of criticism from the recent peer review we are currently attempting to decrease the total length of the article. Creating lists of specific drugs and going into detail about their prevalance and comparative benefits is not condusive to this goal, and is kind of tangential to the general topic. Unless you're looking for a primer on how to drug someone who is going through detox, it's not very useful. I'd like to find a way of summarizing that entire section. Robert Rapplean 19:30, 12 November 2006 (UTC)

- I read through this section, and I'm somewhat on the fence. There is some good info there, but from a layman's point of view I'm not sure that all the specific references add much to the article itself. Perhaps a general summary, rather than detailing the individual drugs in such depth? As Robert points out, some of them sound rather like advertising blurbs. --Doc Tropics Message in a bottle 19:40, 13 November 2006 (UTC)

- There's no question that it's all too easy for an encyclopedia article about a subject to expand, especially when the topic is covered by textbooks, each hundreds of pages long. When I've made entries, I've tried to incorporate answers to questions that patients most frequently ask. Patients often ask about detox...is it safe or dangerous to do on one's own...is it painful or painless...what process is followed...and so on. There are quite a number of protocols out there, but they can be boiled down to two drug classes (barbiturates and benzodiazepines) and two intervention methods (drug challenge followed by taper; CIWA, which is a screen for withdrawal symptoms that will be repeatedly processed with the patient). Treatment is comfortable when correctly carried out and takes a few days. It is not safe to do this alone, though it is safe in an outpatient setting with proper oversight. Obviously, this brief explanation might lead to other questions: what do I mean by drug challenge, for instance, or what are the differences encountered between barbs and benzos. This is where the line might be drawn regarding the scope of the article. Drgitlow 02:08, 25 November 2006 (UTC)

- Given the technical nature of the subject, a certain level of precision is required, and this further implies a certan level of necessary detail. Something that might help keep the article clean would be to write the entry as sparely as possible, while liberally linking to the important related concepts. For example, drug challenge might be an important concept, but explaining it within the article itself is sub-optimum. However, a very reasonable stub article for drug challenge could be created; it need be no more than 2 or 3 paragraphs to start. If Dr. G, or anyone else, would enter a block of relevant text, I would be happy to wikify it and add appropriate links. We could do the same for Treatment diffs of barbs and benzos, or any other important facts/concepts. This would not only streeamline the article, it would improve coverage in the med/sci articles and provide room for future expansion. I'll do the grunt-work if someone will give me the raw material to start with. Just let me know. Doc Tropics 23:38, 29 November 2006 (UTC)

I agree with Doc Tropics on this. DrGitlow's statements within his paragraph are adequate to summarize everything that people need to know on this subject. We can move the specifics to their own articles. This is central to the wiki medium. I think, though, that we need to make a firm statement about which drugs we want to list. I think we can limit it to just naming the general classes of the drugs benzoidazepine and barbituate without going into specific drug names. These should be sufficient for the reader to get an understanding of the process if linked to the appropriate pages. We have to draw a line somewhere, and that seems like a logical spot. How does that sound? Robert Rapplean 18:20, 12 December 2006 (UTC)

- It sounds reasonable to me, but as always, I would defer to the consensus of our local experts : ) Doc Tropics 18:47, 12 December 2006 (UTC)

alcohol abuse costs

Im interested in more country to costs ratios, rather than just that snippet on uk, how about how much alcohol abuse costs other countries Portillo 04:31, 25 November 2006 (UTC)

Cultural and social causes of alcohol addiction

There's very little information here on the cultural and social causes of alcohol addiction. I'm not able to understand the contribution process once a topic has been closed, but the information page on alcohol addiction is pretty skimpy. It's evident that there are custodians of the topic here, but I'm not sure if this is the way to forward additional contributions.

Hoserjoe 09:06, 5 December 2006 (UTC)

Hi, Joe. The reason why there is very little on cultural and social causes is because this information is extremely subjective and as such couldn't be effectively summarized. There are a massive multitude of theories about which specific cultural elements contribute to alcoholism, but the only real consensus is that (a) alcohol availability contributes to alcoholism, and (b) attempts to limit alcohol availability only act to popularize its use. You may argue with this, and many have, but this many argue in a broad multitude of directions. This extremely broad argument makes this the subject of books, not encyclopedia articles. Robert Rapplean 18:12, 12 December 2006 (UTC)

- Joe, you raise an interesting point. Most of us live in societies where alcohol is available whether legally or not. This is a social structure. Without alcohol's availability, alcohol addiction wouldn't arise. One only needs to look at the US history of prohibition to see that although that process failed in many ways, it was an amazing success in terms of reducing the direct and indirect costs, morbidity, and mortality secondary to alcohol intake and addiction. So if you want to indicate that a society that promotes alcohol intake, as America's does through advertising and other measures, is likely to have a higher incidence (rate) of alcoholism than a society that does not promote alcohol use, I think that's a valid point. There are also significant cultural variations; there is a good quantity of literature looking at alcoholism in Jews, in Mormons, and in other groups, for the most part demonstrating significant differences. Part of that may well be genetic, but part may be cultural as well. I'm not sure I'd call these social and cultural issues "causes," but they are most definitely "contributors." Drgitlow 04:16, 19 December 2006 (UTC)

Hey, DG. Although I definitely won't argue about advertising and other forms of popularization increasing the use and secondary problems resulting from use, I can say with considerable authority that the US alcohol prohibion increased both of these instead of decreasing them. In 1918, alcohol use was very much on the decline, and in 1933 is was epidemic. By some estimates alcohol use increased more than ten fold in that time period, and there is nobody who suggests that it actually decreased. Robert Rapplean 18:24, 27 December 2006 (UTC)

- Hi, Robert. I'm afraid you're entirely incorrect. I refer you to the American Journal of Public Health, Feb 2006 issue, page 233-243, and JS Blocker's article, "Did prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public health innovation." I present here a short quote from the article:

- "Nevertheless, once Prohibition became the law of the land, many citizens decided to obey it. Referendum results in the immediate post-Volstead period showed widespread support, and the Supreme Court quickly fended off challenges to the new law. Death rates from cirrhosis and alcoholism, alcoholic psychosis hospital admissions, and drunkenness arrests all declined steeply during the latter years of the 1910s, when both the cultural and the legal climate were increasingly inhospitable to drink, and in the early years after National Prohibition went into effect. They rose after that, but generally did not reach the peaks recorded during the period 1900 to 1915. After Repeal, when tax data permit better-founded consumption estimates than we have for the Prohibition Era, per capita annual consumption stood at 1.2 US gallons (4.5 liters), less than half the level of the pre-Prohibition period."

- Robert, I've never seen any scientific estimates to indicate that alcohol use increased during prohibition. Everything that I found in a literature search of Medline indicates quite the opposite. Happy New Year! Drgitlow 00:50, 1 January 2007 (UTC)

The information that you're posting isn't an accurate measure of alcohol consumption because it's all based on the perception of the officials, and most of it represents the period immediately after prohibition started. The environment at the time was on the pro-prohibition swing if its 70 year cycle, and most areas of the country were already dry by order of local legislation. What prohibition did was put a blanket on all of the country, which largely prevented the dry areas from bringing alcohol in from the wet areas. In truth, the majority of the country really did support prohibition, and went into it with the best of intentions.

Unfortunately, a significant number of people went into it thinking that it would prevent other people from drinking, which was good, not thinking that it would prevent themselves from drinking, which would be bad. In the years previous to prohibition the writing was on the wall that it was on its way, and there was considerable stock piling of alcohol for personal use, kind of like the runs on supermarkets that happen before a blizzard. The black market on alcohol took a while to build up and establish, partially due to lack of demand and partially because it had to build itself up from scratch from close social connections.

There's no surprise that public drunkenness and hospital admissions decreased throughout the prohibition era. That's actually one of the primary health problems with the current war on drugs, that people are unwilling to call attention to their health problems if they're doing something illegal. People generally don't check themselves into a hospital until it's a choice between jail and death, and even then many cut it too close. Forensics weren't up to today's standards and most families were loath to tell the authorities that Uncle Joe drank himself to death, they just say he had a heart attack.

If you want to talk tax records, probably the most telling statistic comes from a count of the number of drinking establishments. In 1918 there were roughly 800 pubs, taverns, and saloons in New York city. In 1933 after prohibition ended, 20,000 speakeasies made an attempt to convert themselves into legitimate businesses. They almost all folded, however, for two reasons. With the legal restrictions removed an individual drinking establishment could be large and obvious, thus having considerable competitive advantage over small, cramped speakeasies. Second, when prohibition ended many people really did stop drinking. It stopped being as elicit and, after a few dozen celebratory drinks, stopped being exciting.

Unfortunately, the self-reported statistics don't tell a full story of what was going on at the time. A good book that you might want to pick up to help understand that time in history is Prohibition : America makes alcohol illegal by Daniel Cohen. Robert Rapplean 20:05, 11 January 2007 (UTC)

Costs of Abuse

I'm puzzled as to why the changes were made to the first paragraph as follows: "Estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse, collected by the World Health Organization, vary from one to six per cent of a country's GDP [1]. One Australian estimate pegged alcohol's social costs at 24 per cent of all drug abuse costs; a similar Canadian study concluded alcohol's share was 41 per cent[2]."

This is not an article about alcohol abuse, but rather an article about alcoholism (alcohol dependence or alcohol addiction are other names for the same entity). Alcohol abuse is a different animal with some similarities. It's sort of like having a reference to rhesus monkeys in an article about gorillas.

Any disagreements with moving these entries to a point later in the article and indicating the differences between abuse and alcoholism, or in removing these entries? Drgitlow 04:41, 11 January 2007 (UTC)

- Hi Drgitlow. The sentence in the first paragraph previously read:

- Alcoholism is one of the world's most costly drug use problems; with the exception of nicotine addiction, alcoholism is more costly to most countries than all other drug use problems combined[citation needed].

- Seeing the tag, I went looking for a source for this statement, i.e. something about the costs of alcoholism to society. Hence the reason for the revision. The reason for the wording is simpler – was not aware of the distinction you point out.

- Am certainly not wedded to the term alcohol abuse, nor to the placement of the information. Why don't you change "alcohol abuse" to "alcoholism" (perhaps if you click on the reference and look at the terms used there you will be able to decide whether these studies are talking about alcoholism or alcohol abuse)? Or move it elsewhere, I don't mind. HMAccount 15:17, 11 January 2007 (UTC)

Hi, HM, and welcome. When I reviewed that edit, I agreed that filling it in with good statistical data was a good idea. OTOH, Dr. Gitlow does make an excellent point about the difference between alcohol addiction and alcohol abuse. The connection between alcoholism and alcohol abuse is somewhat complicated. Alcoholism wouldn't really be a problem if it didn't result in alcohol abuse, but by the same note alcohol abuse isn't just a result of alcholism. Some alcohol abusers are just people having a good time. I don't think that I've ever seen a statistic that calculates "alcohol abuse, but only by alcoholics", and I doubt I ever will. As a result, if we want to show a statistical demonstration of monetary social damages caused by alcoholism, it would need to be embodied as damages caused by alcohol abuse, with the disclamer that this is not a completely accurate measure, just the best available.

This just leaves the question of where we want to put it. The way the text sits, I have the feel that it's probably too much for the first paragraph. Summaries belong there, not full explanations. Can we move it down to Societal Impacts, and just leave a summary there? Robert Rapplean 20:36, 11 January 2007 (UTC)

- Hi Robert, sounds like a great idea! HMAccount 21:14, 11 January 2007 (UTC)

I know I came late to the party, but here is the spectrum as I understand it: Use, Misuse, Abuse, Addiction, Dependancy, Death. Sometimes I see 'heavy use' in there between misuse and abuse, but definitions seem blury. Use is using at all, misuse is using at times that seem inhibitive, abuse is when it starts to infere with daily life/relationships/work, addiction is usually the embodiment of psychological yearnings/feelings of addiction (can be very intense), and dependency is physical addiction/dependence. Death is of course death. JoeSmack Talk 22:46, 11 January 2007 (UTC)

- Hi, Joe. You use those words as if they exist in a linear continuum, but they don't have the same properties. Misuse and abuse both tend to be subjective judgement calls on a person's behavior. Addiction refers to a psychological inability to not use it, and dependence refers to a condition that leads to negative consequences if a person doesn't use it. This is all layed out pretty well in the terminology section. Robert Rapplean 23:13, 15 January 2007 (UTC)

Link somewhat odd

I followed the link to http://www.downyourdrink.org.uk and was curious what their criteria were, so answered the 3-question questionnaire with: three times a week drinking a single alcoholic beverage (i.e., similar to the amount promoted currently as a heart disease prevention.) Their website produced a "possible increased risk of alcohol affecting your health" and a join-up form. I don't know that this is a useful informational link, for that reason. Edit to comment: I just looked into it some more and it seems that these are the first three questions of the AUDIT screening from the World Health Organization. A full online version of it is available at [8]. I think it seems reasonable to replace the site that gives minimal information without a sign-up with the site that has information freely available, so I'm going to do that. A. J. Luxton 07:57, 17 February 2007 (UTC)

- Thanks for doing that research, AJ. That would make "downyourdrink.org.uk" link spam. Robert Rapplean 18:32, 17 February 2007 (UTC)

Criticism by FutharkRed

This may be the poorest article in Wikipedia, from beginning to end, and that is reflected in the discussion here.

One of the most glaring indicators is the decision to bury the most authoritative definition of alcoholism, that of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, in a spot 1/3 through the article--"The DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence represents another approach to the definition of alcoholism"--then asserting that the purpose of the definition is to enable clinical research! No, it is not 'another approach', it is that of the highest level of disease classification, by those specializing in the field, and its purpose is to best enable treating said disease. It is the diagnosis used by most in the field, is used in filing insurance claims for treatment, is what is meant, from a scientific point of view, by 'alcoholism'.

That definition is "...maladaptive alcohol use with clinically significant impairment as manifested by at least three of the following within any one-year period: tolerance; withdrawal; taken in greater amounts or over longer time course than intended; desire or unsuccessful attempts to cut down or control use; great deal of time spent obtaining, using, or recovering from use; social, occupational, or recreational activities given up or reduced; continued use despite knowledge of physical or psychological sequelae." That is alcoholism, not what has been tossed around either in this article or this discussion.

Alcoholism has been recognized for some time as a primary, progressive disease, involving addiction to alcohol (with both tolerance for and withdrawal from the alcohol as major defining features). The DSM-IV categorizes it, in fact, among the psychotic disorders. There is strong evidence for genetic factors in susceptibility to the addiction, as well as several distinctions in the ways that alcoholics process alcohol, metabolically and physiologically, compared to the general population.

Negative consequences of drinking are not diagnostic of the disease; inability to stop in spite of such consequences may be.

Socially, alcoholism's effects far exceed those of all other drugs combined, especially inasmuch as it is considered among the leading causes of death. ('Nicotine', as opposed to smoking, is not in the same order of magnitude--how the claims of its 'greater cost' is allowed to stand uncited is another mystery.)

As for the range of its effects, the 19th century suggestion that you could study all medicine, simply by studying the one disease of syphillis, is more than matched currently by substituting the study of alcoholism. It has an unparallelled range of effects, physical and mental, and that holds as well in its effects throughout the population. Estimates of susceptibility to the disease itself range as high as 10% of the population (potential alcoholics); and the effects extend to all those in contact with the active alcoholic, an enormous part of the population, compared with that affected by any other disease.

Given this, how one can choose to seriously discuss alcoholism, the disease, while moving the 'disease theory' elsewhere, escapes me. Who on earth authorized any such travesty? To discuss 'two (professionally undifferentiated) forms' of alcoholism, as is done in this discussion, is nonsense ... to anyone who does know the disease. The former version mentioned here is not considered alcoholism at all, 'professionally'. It may be a problem, true, and one that can use some treatment or prevention (as is an issue, for instance, on many college campuses), but this is not alcoholism in itself. The very way of phrasing much of this, referring to "professional disagreement", leads to the question, as to whence the greater expertise of the current authors arises.

As one among many non-professional indicators, I'd point out that 'endorphins' (which are not morphine-related) have virtually nothing to do with alcohol or alcoholism, popular though the notion may be. Alcohol has its own neurochemical effects, in the first place. The process of alcohol addiction has to do with conversion of alcohol metabolites in the alcoholic to THIQs (tetrahydroisoquinolines), quite similar in fact to the structure of morphine. The addiction itself becomes self-propelling, and requires no positive motivator the further it progresses ... other than the negative one of staving off withdrawal.

Likewise, the notion that the turning point in the disease is when "others help them realize" the negative road they are on, is spectacularly untrue to life. One of the most glaring features of alcoholism, is its long-term imperviousness both to consequences and to the input of others. The single most effective agent in recovering from alcoholism, Alcoholics Anonymous, is in no way based on helping alcoholics realize the negatives involved, which they are all too often aware of (though they may be unaware that alcohol is the cause of the trouble, rather than a failing solution.) It is based on showing that there is a real, positive alternative, such as their own alcoholic thinking suggests is impossible.

As with most diseases, the primary question for most people is, what can be done about it. Here the article is woefully poor. The authors list 5 'mutual help' organizations, for instance, as though they were of equivalent value, although only one has any substantial rate of success in dealing with the disease. Likewise, suggesting 'group therapy or psychotherapy' for "underlying psychological issues" both implies that the alcoholism may be a secondary rather than primary disease, contrary to current thinking, and overlooks the history of failure in that area--aside from such specialized treatment as is aimed entirely at abstention, and generally recommends participation in A. A.

The notion that "the American Psychiatric Association considers remission to be a condition where the physical and mental symptoms of alcoholism are no longer evident, regardless of whether or not the person is still drinking" (emphasis mine) is uncited, unlikely, and contrary to virtually every current thought on the subject. Agreement is effectively universal that an alcoholic cannot drink safely at all, ever again, that the first remedy is complete abstinence--except for the opinion of the authors here. In fact, they uncritically list Moderation Management as a 'resource', along with Alcoholics Anonymous, MM taking the position that alcoholics can learn to drink safely--without noting that MM's founder is herself in prison due to subsequent vehicular double manslaughter, while having a blood alcohol level 3 times the legal limit.

In fact, the entire discussion which is entertained on that question, under the heading of 'Rationing and Moderation', runs counter to any professional notion of alcoholism. There may indeed be "harm reduction" in other areas of drug abuse and addiction--much of the harm of heroin addiction, for instance, is not directly caused by the chemical, as by all that goes with it. In the case of alcohol and the alcoholic, it is the alcohol 100%, and there is no such thing as 'harm reduction' by any form of controlled drinking.

It is a truism that non-alcoholics never even think about "controlling their drinking" ... and that alcoholics, as the disease progresses, do think about it, and can't. At this point, for the authors to even be discussing the issue for more than one sentence, indicates that it is not alcoholism they are speaking of. They should not be writing about alcoholism, at all. FutharkRed 04:04, 3 February 2007 (UTC)

- You know, I don't even know where to start on this. You are so thorougly woefully uninformed about alcoholism that you could only be a medical professional or an AA councilor. Possibly a psychiatrist, as they are the ones who usually insist that the DSM knows all. Pretty much everything in this entire article has been backed up one side and down the other by papers, books, and studies. At one point we had to start clearing off the references because some sentances had more reference marks than they did words. It's not like all of this information was made up by somebody. Please take a look in the archives, and present your own evidence that conflicts with what you see here. We all had to.

- For starters, cigarette smoking kills an estimated 440,000 americans each year, whereas alcohol only kills 80,000 by the same (NIDA) accounting. No, I'm not going to start tallying up wife beatings and drunken bar fights. Endorphin release is a well known effect of alcohol consumption, although most people attribute its addictive effects to the dopamine that the endorphins trigger the release of. By anyone who's actually looked at the statistics, AA is less effective than no treatment whatsoever. Even playing patty-cake has higher success rates than AA meetings. - Robert Rapplean 07:59, 3 February 2007 (UTC) Most people that are in jail are in there for dealing with drugs. 5 February 2007

- Robert, your comment, "You are so thorougly woefully uninformed about alcoholism that you could only be a medical professional or an AA councilor," is hostile and uncalled for. You're better than that! Drgitlow 19:00, 11 February 2007 (UTC)

- *sigh* Ok, I'll agree that it was hostile and unproductive. Having put untold hours into reconciling the highly varied ideas of what alcoholism is, and having someone spout This may be the poorest article in Wikipedia at us kind of puts me on edge. Nonetheless, I do owe FurtharkRed an apology, that was very unprofessional of me.Robert Rapplean 19:33, 14 February 2007 (UTC)

FutharkRed, I agree with 96% of what you wrote, and indeed the version of this article that I wrote many months ago reflected the standard understanding of the scientific and medical communities that you accurately represent. I was broadly attacked by others here and after several months we compromised on the entire article, which as it stands is tolerable by many but I don't think any of us would say it is accurate from any single perspective. Part of the compromise, which I still strongly disagree with (but I was firmly outvoted), involved the removal of the entire medical understanding of alcoholism as a disease. Ridiculous, I know, but that's the way Wikipedia works.

By the way, the area where we disagree, and I'll be as clear as I can be here: As defined by DSM-IV, there are a variety of symptoms that constitute the disease of alcohol dependence. Note that quantity and frequency of use are not included within these symptoms. That is critically important, as it reflects the fact that alcohol dependence is not defined by amount of use or frequency of use. Now look at how DSM-IV defines remission on p. 196 of the TR edition. Remission refers to the criteria for dependence or abuse, not to amount of use. As a result, one can continue to have substance use but also have remission. That is the way the definition is generally understood by addiction medicine specialists. That said, I of course agree with you that abstinence is required for recovery. The psychiatric definition of disease remission is not equivalent to the medical definition of recovery. In fact, many of us in the medical addiction field don't use the psychiatric definition but rather use the medical one (JAMA 1992 article referred to elsewhere here). So I suspect that you and I completely agree on what's necessary to treat patients, but we appear to disagree on the meaning and intent of the DSM definition, and that's simply an academic question, no? Drgitlow 18:56, 11 February 2007 (UTC)

- Dr. G., thank you very much. Not just for your kind remarks, and your thoughts on the subject in question ... but for restoring mine to the discussion page in the first place! They were originally appended to the discussion of the lead paragraph, and almost immediately removed by the author of that paragraph, as being beyond discussion!

Actually, I moved it to the bottom of the discussion page, where it now resides. As mentioned in the comment in history, it opens numerous new discussions based on one that was archived quite a long time ago, and as such deserved its own heading.Robert Rapplean 19:33, 14 February 2007 (UTC)

- That removal, with the remover's comments, would have had me avoiding work on the article for a long while. I don't refer to the personal slant, but to the absolute lack of objectivity, from what would appear to be the article's lead author! To cite "a medical professional or an AA councilor. Possibly a psychiatrist" as certain sources of ignorance on the subject; to claim that "AA is less effective than no treatment whatsoever"; to remove the disease concept, AMA or APA or otherwise, from the article--all of these indicate an extraordinarily prejucidial approach. And removing criticism in such a manner indicated little chance for a direct approach to the article.

As evidensible here, this is a collection of things that need to be argued individually.

To cite "a medical professional or an AA councilor. Possibly a psychiatrist" as certain sources of ignorance on the subject

We get a very broad selection of people here who insist that their perspective on alcholism is the only possible one. These range from a variety of medical professionals (mental and physical health) to alcoholism councilors, religious fanatics, and outright bigots. There is a lot of vertical information passed within these groups, but not a whole lot of horizontal information passed between them. Those with the largest and most professional groups are the ones who most strongly insist that their view of alcoholism is the one and only true view of alcoholism, and they generally take the greatest amount of evidence to convince them that it isn't as black and white as all that. They take their professional perspective and years of experience as a bedrock to insist that no other group could possibly have a clue about the topic. The resulting arguments can be very frustrating and time consuming.

to claim that "AA is less effective than no treatment whatsoever"

You should have a look at the Orange Papers, specifically their page on effectiveness. I'm not going to say that this is the only perspective that's valid - we try to recognize all perspectives, including this one. Among the many peer reviewed studies that he sites, there's one where they had the patients gather in an AA-like meeting and play Patty Cake. This "treatment program" had statistically identical results to the AA meetings. So I was exagerating when I said "less effective", my apologies, please replace that with "no more effective".

A fair accounting of AA indicates a dropout rate of about 95%. AA doesn't consider these dropouts to be part of their failure rate, but they are nonetheless people for whom the AA program was a failure. This 5% success rate is roughly equivalent to the rates for spontaneous remission, which suggests that AA has no meaningful effect at all. There is an immense body of evidence that supports this idea, and as such we aren't really swayed by arguments that AA is the only effective treatment option. Robert Rapplean 19:33, 14 February 2007 (UTC)

- Just a few notes about this depiction of A. A., and the methods of the article and the discussion.

- It appears that declarations by the American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association, with only slight differences in terms and detail, to the effect that alcoholism is a primary disease, are considered of dubious value "for definitive or treatment purposes". On the other hand, something like the anonymous "Orange Papers" web site qualifies for authoritative citation.

Do we have to go through this every four months? FYI, the definition of "Alcoholism is a primary, chronic disease..." was one originally proposed for the opening definition in this article. It was altered severely to what it currently is because anybody who understood the terms primary and chronic probably wouldn't be going to Wikipedia for their information. Unsuitability for the audience had more to do with it than medical, clinical accuracy. As you seemed to have completely missed (and I'm REALLY not enjoying repeating myself today), I didn't say that this is the only perspective that's valid - we try to recognize all perspectives, including that of the AMA and APA. Put another way, we cannot dismiss any of these perspectives if they are supported by multiple clinical studies.

- How does Wikipedia go about weighing sources? Surely there should be something a little better, for such strong declarations? Perhaps the original "peer-reviewed" research papers, if really meaningful and verifiable?

The Orange Papers are really nothing more than a convenient way of referencing a large number of these kinds of papers. I'll make it easy on you and copy the citations that answer the many accusations that you make, making it obvious that you really have no intention of actually considering anyone else's perspective.

- Bearing in mind of course that some of the most famous such 'research' of the past, especially that devoted to proving that alcoholics could learn to drink safely, turned out to be fraudulent.

Logic foul: Hasty Generalization

- But can the "Orange Papers" be considered objective by any standards? “Agent Orange”, indeed.

Logic foul: Ad Hominem attack

- Regarding our standards for objectivity, and the citing of sources when a matter might be questioned, how does the expression "a fair accounting" serve for a question such as the effectiveness of A. A? Who is doing the accounting, of what, and how … and, perhaps, why? More bluntly, A. A. being what it is, how could any such "accounting" be done at all? The only records A.A. keeps are of groups that have registered, and a rough survey every few years, to estimate the global numbers and composition of those attending meetings at the time, at the request of social scientists for their own research. The surveys appear to show a fairly steady 2 million people world-wide at an A. A. meeting on a given day, 1.25 million living in the U. S. and Canada. No records of individual attendance or membership are kept at all.

- That is, at no level does A. A. keep the kind of records, or set criteria for 'membership' (which a person might then be said to "drop out" of), or track people that do or don't go to meetings, or set standards of success and failure, that would make any such "accounting" possible, "fair" or otherwise. So on what could such a statement possibly be based? And why is it put in these terms, of “dropping out” and “failure”?

I do wish you would actually read the Orange Papers before maligning them so thoroughly. I quote:

For many years in the 1970s and 1980s, the AA GSO (Alcoholics Anonymous General Service Organization) conducted triennial surveys where they counted their members and asked questions like how long members had been sober. Around 1990, they published a commentary on the surveys: Comments on A.A.'s Triennial Surveys [no author listed, published by Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc., New York, no date (probably 1990)]. The document has an A.A. identification number of "5M/12-90/TC". Averaging the results from the five surveys from 1977 to 1989 yielded these numbers: