Gilbert and Sullivan

Librettist William Schwenck Gilbert (1836–1911) and composer Arthur Seymour Sullivan (1842–1900) collaborated on a series of fourteen comic operas in Victorian England between 1871 and 1896.

The Gilbert and Sullivan works have enjoyed broad and enduring international success, particularly in the English-speaking world. H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado, in particular, introduced innovations in content and form that directly influenced the musical theatre of the 20th century.[1] Their works have become known as the Savoy Operas, after the Savoy Theatre in London, which was built in 1881 by their producer, Richard D'Oyly Carte, to present their operas.[2]

Gilbert, who wrote the words, created fanciful worlds for these operas, where an absurdity is taken to its logical conclusion. In these worlds fairies rub elbows with English lords, flirting is a capital offence, gondoliers ascend to the monarchy, and pirates turn out to be noblemen who have gone wrong. The lyrics employ double (and triple) rhyming and punning, and served as a model for such 20th century Broadway lyricists as P.G. Wodehouse,[3] Cole Porter,[4] Ira Gershwin,[5] and Lorenz Hart.[1] Sullivan, the composer, who also wrote many hymns, oratorios, part songs and orchestral works, contributed tuneful and memorable melodies that could convey both humour and pathos, and his musical ingenuity and craft equalled or surpassed that of many important classical composers.[6]

Gilbert and Sullivan sometimes had a strained working relationship, partly caused by the fact that each man saw himself allowing his work to be subjugated to the other's, and partly caused by the opposing personalities of the two – Gilbert was often confrontational and notoriously thin-skinned (though prone to acts of extraordinary kindness), while Sullivan eschewed conflict. In addition, Gilbert imbued his libretti with "topsy-turvy" situations in which the social order was turned upside down. After a time, these subjects were often at odds with Sullivan's desire for realism and emotional content.[7] In addition, Gilbert's political satire often poked fun at those in the circles of privilege, while Sullivan was eager to socialize among the wealthy and titled people who would become his friends and patrons.[8]

For over a century, until it closed in 1982, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company performed the Gilbert and Sullivan operas (controlling the British copyrights to the works until 1961) and exercised great influence over the style and traditions for performing these works. Today, many cities, churches, schools, and universities have their own amateur Gilbert and Sullivan performing groups.[9] The most popular G&S works are performed from time to time by major opera companies,[10] and there are a number of professional repertory companies that specialize in G&S.[11] In addition, every summer, there is a 3-week-long International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival in Buxton, England.

Beginnings

Gilbert before Sullivan

Gilbert was born in London on November 18, 1836. His father William was a naval surgeon who later became a novelist and short story writer.[12] Gilbert illustrated some of his father's stories,[12] and in 1861, he began to write illustrated stories, poems and articles of his own to supplement his income. The poems, published as the Bab Ballads, and the short stories would later be mined as a source of ideas for his plays, including the Gilbert and Sullivan operas.[13] In the Bab Ballads, Gilbert had developed a unique "topsy-turvy" style, where the humour was derived by setting up a ridiculous premise and working out its logical consequences, however absurd. Gilbert had already produced half of his more than 75 plays and operas by 1871, and he had developed his innovative theories on the art of stage direction, following theatrical reformer Tom Robertson.

Theatre in Britain, at that time Gilbert began writing, was in disrepute,[14] and Gilbert helped to reform and elevate the respectability of the theatre, especially beginning with his six family-friendly German Reed Entertainments, which were short comic operas.[15] At a rehearsal for Ages Ago in 1869, one of these entertainments, composed by Frederic Clay, Clay introduced Gilbert to Arthur Sullivan.[16] Two years later, Gilbert and Sullivan would create their first collaboration together.

Those two intervening years were very productive for Gilbert and continued to shape his theatrical style. He continued to write humorous verse, stories and plays, including the comic operas Our Island Home (1870) and A Sensation Novel (1871), and the blank verse comedies The Princess (1870), The Palace of Truth (1870), and Pygmalion and Galatea. Gilbert would later find inspiration in many of his early plays and operas for the collaborations with Sullivan.

Sullivan before Gilbert

Sullivan was born in London on May 13 1842. His father was a military bandmaster, and by the time Arthur had reached the age of 8, he was proficient with all the instruments in the band. In school he began to compose anthems and songs, and in 1856, he received the first Mendelssohn prize and studied at the Royal Academy of Music and at Leipzig, where he also took up conducting. His graduation piece, completed in 1861, was a set of incidental music to Shakespeare's The Tempest. Revised and expanded, it was performed at the Crystal Palace in 1862 and was an immediate sensation. He began building a reputation as England's most promising young composer, composing a symphony, a concerto and his successful Overture di Ballo, in 1870.[17]

His early works for the voice included The Masque at Kenilworth (1864); an oratorio, The Prodigal Son (1869); and a dramatic cantata, On Shore and Sea (1871). He composed a ballet, L'Île Enchantée and incidental music for a number of Shakespeare plays. Other early pieces that were praised were his Irish Symphony, Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, and Overture in C (In Memoriam) (all three of which premiered in 1866).[18] These commissions, however, were not sufficient to keep Sullivan afloat during this period. He worked as a church organist and composed numerous hymns, popular songs, and parlour ballads.[19]

Sullivan's first successful comic opera was Cox and Box (1866), followed by The Contrabandista (1867), both with librettos by F. C. Burnand.

Operas

First collaborations: Thespis and Trial by Jury

The first Gilbert and Sullivan collaboration was Thespis, produced at the large Gaiety Theatre, an extravaganza in which the gods of the classical world, who have become elderly and ineffective, are temporarily replaced by a troupe of actors and actresses. The piece echoed and may even have borrowed from Orpheus in the Underworld and La belle Hélène,[20] two of Offenbach's mixtures of political satire and grand opera parody,[21] which (in translation) then dominated the English musical stage. Thespis opened at the Gaiety Theatre on Boxing Day in 1871 and ran for 63 performances. Gilbert directed the production himself, as he did all of the G&S operas. Unlike the later G&S works, however, Thespis was hastily prepared and of a more risqué nature, like Gilbert's earlier travesties, with a broader style of comedy that allowed for improvisation by the actors. Two of the male characters were played by women, whose shapely legs were put on display in a fashion that Gilbert later condemned. The musical score to Thespis was never published and is now lost, except for one song that was published separately, a chorus that was re-used in The Pirates of Penzance, and the Act II ballet. There have been numerous revivals, either with original scores or adaptations of Sullivan's other music.[22]

Thespis outran five of its nine competitors for the 1871 holiday season and was later revived for a benefit performance. No one at the time, however, anticipated that this was the beginning of a great collaboration, and Gilbert and Sullivan did not have occasion to work together for another four years. Gilbert worked with Clay on Happy Arcadia (1872) and with Alfred Cellier on Topsyturveydom (1874), as well as writing several other operetta libretti, farces, extravaganzas, fairy comedies, dramas, adaptations from novels, and translations from the French. Sullivan completed his Festival Te Deum (1872), another oratorio, The Light of the World (1873), his only song cycle The Window; or, The Song of the Wrens (1871), incidental music to The Merry Wives of Windsor (1874) and more hymns, including "Onward, Christian Soldiers" (1872), songs and parlour ballads. In short, during these years, each man became more eminent in his field.

By early 1875, Richard D'Oyly Carte was managing the Royalty Theatre, and he needed a short opera to be played as an afterpiece to Offenbach's La Périchole. Gilbert had already written such a short piece on commission from producer-composer Carl Rosa, whose wife's unexpected death had left the libretto an orphan. Carte suggested that it be set to music by Sullivan. Sullivan was delighted with it, and Trial by Jury was composed in a matter of weeks. The little piece, starring Sullivan's brother, Fred, as the Learned Judge, was a runaway hit, outlasting the run of La Périchole and being revived at another theatre.[23]

Sorcerer to Pirates

The Sorcerer (1877) was the first full-length example of what came to be known as the Savoy Operas (although the Savoy Theatre had yet to be built). Carte, who was now interested in developing an English form of light opera that would displace the bawdy burlesques and badly translated French operettas then dominating the London stage, asked Gilbert for a comic opera that would serve as the centrepiece for an evening's entertainment. Gilbert found a subject in one of his short stories, "The Elixir of Love", which concerned a Cockney businessman who happened to be a sorcerer, a purveyor of blessings (not much called for) and curses (very popular). Gilbert and Sullivan were tireless taskmasters, seeing to it that The Sorcerer opened as a fully polished production at the Opera Comique, in marked contrast to the under-rehearsed Thespis.[24] The triumvirate of Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte was now an established entity that would survive through a dozen more collaborations.

With The Sorcerer, the D'Oyly Carte repertory and production system came into being. Previously, Gilbert had constructed his plays around the established stars of whatever theatre he happened to be writing for, as had been the case with Thespis. From The Sorcerer onwards, Gilbert would no longer hire stars; he would create them. He and Sullivan selected the performers, writing their operas for ensemble casts rather than individual stars. Gilbert oversaw the designs of sets and costumes, and he directed the performers on stage. Sullivan personally oversaw the musical preparation. The result was a new crispness and polish in the English musical theatre.

The libretto of The Sorcerer relied on stock character types, many of which were familiar from European opera: the heroic protagonist (tenor) and his love-interest (soprano); the elderly woman with fading charms (contralto) and a supporting bass-baritone or two. The "patter" or comic baritone, was often the leading role of their comic operas. This character most often gets to sing the speedy patter songs. Gilbert and Sullivan fully integrated the male and female choruses into the action, making them, collectively, as important as any principal character.

The repertory system ensured that the comic patter man who would perform the role of the sorcerer, John Wellington Wells, would become the ruler of the Queen's navy as Sir Joseph Porter in H.M.S. Pinafore, then join the army as Major-General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance, and so on. Similarly, Mrs. Partlet in The Sorcerer would transform into Little Buttercup in Pinafore, then into Ruth, the piratical maid-of-all-work in Pirates. Relatively unknown performers whom Gilbert and Sullivan engaged for The Sorcerer and Pinafore would stay with the company for many years, becoming stars of the Victorian stage. These included George Grossmith, the comic baritone; Rutland Barrington, lyric baritone and character actor; Richard Temple, the bass-baritone; Jessie Bond, the soubrette; and Rosina Brandram the contralto.

Gilbert and Sullivan scored their first international hit with H.M.S. Pinafore (1878), satirizing incompetent government officials, the Royal Navy and the English obsession with social status. Hundreds of unauthorized, or "pirated", productions of this work appeared in America.[25] The Pirates of Penzance (1879), written in a fit of pique at the American copyright pirates, also poked fun at grand opera conventions, sense of duty, family obligation, and the relevance of a liberal education.

Savoy Theatre: Patience to Gondoliers

Patience (1881) satirized the aesthetic movement in general, and the poet and aesthete Algernon Swinburne in particular, as well as male vanity and chauvinism in the military. During the run of Patience, Carte built the large, modern Savoy Theatre, which became the partnership's permanent home. It was the first theatre (indeed the world's first public building) to be lit entirely by electric lighting.[26] Iolanthe (1882) was the first of their works to open at the Savoy. It poked fun at English law and the House of Lords and made much of the war between the sexes. Princess Ida (1884) spoofed women's education and male chauvinism.

In 1882, Gilbert had a telephone installed in his home and at the prompt desk at the Savoy Theatre, so that he could monitor performances and rehearsals from his home study. Gilbert had referred to the new technology in Pinafore in 1878, only two years after the device was invented and before London even had telephone service. Sullivan also installed a telephone at his home, and on May 13 1883, at a party to celebrate the composer's 41st birthday, the guests, including the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), heard a direct relay of parts of Iolanthe from the Savoy. According to Ian Bradley, this was probably the first live "broadcast" of an opera.[27]

The most successful of the Savoy Operas was The Mikado (1885), which made fun of English bureaucracy in a Japanese setting. Ruddigore (1887), a topsy-turvy take on Victorian melodrama, was less successful. The Yeomen of the Guard (1888), their only joint work with a serious ending, concerns a pair of strolling players—a jester and a singing girl—who are caught up in a risky intrigue at the Tower of London. The Gondoliers (1889) was a recapitulation of many of the themes of the earlier operas, taking place in a kingdom ruled by a pair of gondoliers who attempt to remodel the monarchy in a spirit of "republican equality."[28]

Carpet quarrel

Gilbert and Sullivan quarrelled several times over the choice of a subject. After both Princess Ida and Ruddigore, which were less successful than the seven other operas from H.M.S. Pinafore through The Gondoliers, Sullivan asked to leave the partnership, saying that he found Gilbert's plots repetitive and that the operas were not artistically satisfying to him. While the two artists worked out their differences, Carte kept the Savoy open with revivals of their earlier works. On each occasion, after a few months' pause, Gilbert responded with a libretto that met Sullivan's objections, and the partnership was able to continue successfully.[29]

During the run of The Gondoliers, however, Gilbert challenged Carte over the expenses of the production. Carte had charged the cost of a new carpet for the Savoy Theatre lobby to the partnership. Gilbert believed that this was a maintenance expense that should be charged to Carte alone. As scholar Andrew Crowther has explained:

- After all, the carpet was only one of a number of disputed items, and the real issue lay not in the mere money value of these things, but in whether Carte could be trusted with the financial affairs of Gilbert and Sullivan. Gilbert contended that Carte had at best made a series of serious blunders in the accounts, and at worst deliberately attempted to swindle the others. It is not easy to settle the rights and wrongs of the issue at this distance, but it does seem fairly clear that there was something very wrong with the accounts at this time. Gilbert wrote to Sullivan on 28 May, 1891, a year after the end of the "Quarrel", that Carte had admitted "an unintentional overcharge of nearly £1,000 in the electric lighting accounts alone."[29]

Sullivan sided with Carte, who was building a theatre in London for the production of new English grand operas, with Sullivan's Ivanhoe as the inaugural work. While the protracted quarrel worked itself out in the courts and in public, Gilbert wrote The Mountebanks with Alfred Cellier and the flop Haste to the Wedding with George Grossmith,[30] and Sullivan wrote Haddon Hall with Sidney Grundy, in addition to Ivanhoe.

In 1891, after many failed attempts at reconciliation by the pair and their producer, Richard D'Oyly Carte, Gilbert and Sullivan's music publisher, Tom Chappell, stepped in to mediate between two of his most profitable artists, and within two weeks he had succeeded.[31]

Last works and legacy

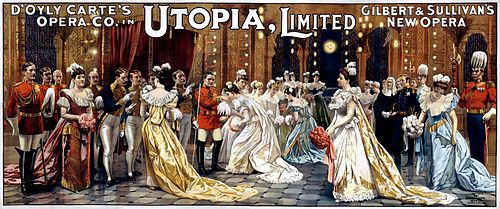

Utopia, Limited (1893), their penultimate opera, was a very modest success, and The Grand Duke (1896) was an outright failure.[32] Neither work entered the "canon" of regularly-performed Gilbert and Sullivan works until the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company made the first complete professional recordings of the two operas in the 1970s. Gilbert also offered a third libretto to Sullivan (His Excellency, 1894), but Gilbert's insistence on casting Nancy McIntosh, his protégée from Utopia, led to Sullivan's refusal.[33]

After The Grand Duke, the partners saw no reason to work together again. Sullivan, by this time in exceedingly poor health, died four years later, although to the end he continued to write new comic operas for the Savoy with other librettists, most successfully The Rose of Persia (1899), and The Emerald Isle (1901) (finished by Edward German after Sullivan's death). Gilbert went into semi-retirement, although he continued to direct revivals of the Savoy Operas and wrote new plays occasionally. He wrote only one more comic opera, Fallen Fairies (1909; music by Edward German), which was not a success. Richard D'Oyly Carte died in 1901, and his widow, Helen, and then his son, Rupert, followed by his granddaughter, Bridget, continued to direct the activities of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, which staged revivals of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas until it closed in 1982.

Because of the unusual success of the operas, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company were able, from the start, to license the works to other professional companies, such as the J. C. Williamson Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Company, and to amateur societies. For almost a century, until the British copyrights expired in 1961, and even afterwards, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company influenced productions of the operas worldwide, creating a "performing tradition" for most of the operas that is still referred to today by many directors. D'Oyly Carte produced several attractive recordings of most of the operas, helping to keep them popular through the decades. Today, numerous repertory companies, opera companies and amateur societies continue to produce the works.

Cultural influence

In the past 125 years, Gilbert and Sullivan have pervasively influenced popular culture in the English-speaking world.[34] In addition, lines and quotations from the Gilbert and Sullivan operas have become part of the English language, such as "short, sharp shock", "What never? Well, hardly ever!", "let the punishment fit the crime", and "A policeman's lot is not a happy one".[35][36] The operas have influenced political style and discourse, literature, film and television, and have been widely parodied by humorists.

The American and British musical owes a tremendous debt to G&S, who were admired by and copied by early authors and composers such as Ivan Caryll, Adrian Ross, Lionel Monckton, P. G. Wodehouse, Guy Bolton, Victor Herbert, and Ivor Novello, and later Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein II, and Andrew Lloyd Webber.[37]

Gilbert and Sullivan's work provides a rich cultural resource outside of their influence upon musicals. The works of Gilbert and Sullivan are themselves frequently pastiched. Well known examples of this include Tom Lehrer's The Elements, Allan Sherman's and Anna Russell's famous routines, and the animated TV series, Animaniacs' HMS Yakko episode. Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas are commonly referenced in literature, film and television in various ways that include use of Sullivan's music or where action occurs during a performance of a Gilbert and Sullivan opera. There are also a number of Gilbert and Sullivan biopics, such as Mike Leigh's Topsy-Turvy.

The musical is not, of course, the only cultural form to show the influence of G&S. Even more direct heirs are those witty and satrical songwriters found on both sides of the Atlantic in the twentieth century like Michael Flanders and Donald Swann in the United Kingdom and Tom Lehrer in the United States. The influrence of Gilbert is discernible in a vein of British comedy that runs through John Betjeman's verse via Monty Python and Private Eye to... television series like Yes, Minister... where the emphasis is on wit, irony, and poking fun at the establishment from within it in a way which manages to be both disrespectful of authority and yet cosily comfortable and urbane.

— Ian Bradley, Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan ISBN 0195167007

It is not surprising, given the focus of Gilbert on politics, that politicians have often found inspiration in these works. U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist added gold stripes to his judicial robes after seeing them used by the Lord Chancellor in a production of Iolanthe,[38] Alternatively, Lord Chancellor Charles Falconer is recorded as objecting so strongly to Iolanthe's comic portrayal of Lord Chancellors that he supported moves to disband the office.[35] British politicians, beyond quoting some of the more famous lines, have delivered speeches in the form of Gilbert and Sullivan pastiches. These include Conservative Peter Lilley's speech mimicking the form of "I've got a little list" from The Mikado, listing those he was against, including "sponging socialists" and "young ladies who get pregnant just to jump the housing queue".[35]

A note on terminology

This article refers to the Gilbert and Sullivan works as 'comic operas' or 'Savoy operas', rather than 'operettas'. This is because Gilbert, Sullivan, Carte and other Victorian-era British composers, librettists and producers, including the German Reeds, Frederic Clay, and F. C. Burnand, as well as the contemporary British press and literature, called British works of this kind 'comic operas' to distinguish their content and style from that of the continental European operettas that they wished to displace, as discussed above. Gilbert and Sullivan scholars since that time continue to refer to these works as 'comic operas'.[39] However, the Penguin Opera Guides and other general music dictionaries and encyclopedias classify G&S as operetta.[40]

Collaborations

Major works

- Thespis, or, The Gods Grown Old (1871)

- Trial by Jury (1875)

- The Sorcerer (1877)

- H.M.S. Pinafore, or, The Lass That Loved a Sailor (1878)

- The Pirates of Penzance, or, The Slave of Duty (1879)

- The Martyr of Antioch (cantata) (1880) (Gilbert modified the poem by Henry Hart Milman)

- Patience, or Bunthorne's Bride (1881)

- Iolanthe, or, The Peer and the Peri (1882)

- Princess Ida, or, Castle Adamant (1884)

- The Mikado, or, The Town of Titipu (1885)

- Ruddigore, or, The Witch's Curse (1887)

- The Yeomen of the Guard, or, The Merryman and his Maid (1888)

- The Gondoliers, or, The King of Barataria (1889)

- Utopia, Limited, or, The Flowers of Progress (1893)

- The Grand Duke, or, The Statutory Duel (1896)

Parlour ballads

- The Distant Shore (1874)

- The Love that Loves Me Not (1875)

- Sweethearts (1875), based on Gilbert's 1874 play, Sweethearts

Alternative versions

- Non-English language

Gilbert and Sullivan operas have been translated into many languages, including Portuguese, Yiddish, Hebrew, Swedish, Danish, Estonian, Spanish (including Pinafore, reportedly, in zarzuela style), and many others.

There are many German versions of Gilbert and Sullivan operas, including the popular Der Mikado. There is even a German version of The Grand Duke. Some German translations were made by Friedrich Zell and Richard Genée, librettists of Die Fledermaus, Eine Nacht in Venedig and other Viennese operettas. They even translated such a lesser-known opera as Sullivan's The Chieftain ("Der Häuptling").

- Ballets

- Pirates of Penzance - The Ballet! (formerly called Pirates! The Ballet)

- Pineapple Poll - from a story by Gilbert - and music by Sullivan

- Adaptations

- The Swing Mikado (1938) (Chicago) All-black cast

- The Hot Mikado (1939) and Hot Mikado (1986)

- The Jazz Mikado

- The Black Mikado

- The Cool Mikado

- Hollywood Pinafore

- The Pirate Movie (1982), starring Christopher Atkins and Kristy McNichol.

- Parson's Pirates by Opera della Luna

- The Ghosts of Ruddigore by Opera della Luna

- Di Yam Gazlonim A Yiddish adaptation of Pirates by Al Grand that continues to be performed frequently in the United States.

- The Ratepayers' Iolanthe 1984 Olivier Award-winning musical.

See also

- D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

- Gilbert and Sullivan performers

- People associated with Gilbert and Sullivan

- The International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival, held annually in Buxton, England

Notes

- ^ a b Downs, Peter. "Actors Cast Away Cares". Hartford Courant, October 18 2006. Available for a fee at courant.com archives.

- ^ Savoy Theatre, London. thisistheatre.com, Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ PG Wodehouse(1881–1975). guardian.co.uk, Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Lesson 35 — Cole Porter: You're the Top. PBS.org, American Masters for Teachers, Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Furia, Phillip. Ira Gershwin: The Art of a Lyricist. Oxford University Press, Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Arthur Sullivan 1842–1900. The Musical Times, December, 1900. Archived at the internet archive, 2005-11-04. Note the quote from George Grove.

- ^ See, e.g. Ainger, p. 288, or Wolfson, p. 3

- ^ See, e.g. Jacobs, Arthur (1992); Crowther, Andrew, The Life of W.S. Gilbert. The Gilbert and Sullivan archive at Boise State University, Retrieved on 2007-05-21; and Bond, Jessie, The Reminisences of Jessie Bond: Chapter 16. The Gilbert and Sullivan archive at Boise State university, Retrieved on 2007-05-21

- ^ Websites of Performing Groups. The Gilbert and Sullivan archive at Boise State university, Retrieved on 2007-05-21

- ^ Performances, by city — Composer: Arthur Sullivan. operabase.com, Retrieved on 2007-05-21

- ^ For example,NYGASP, Carl Rosa Opera Company, Somerset Opera, Opera della Luna, Opera a la Carte, Skylight opera theatre, Ohio Light Opera, and Washington Savoyards

- ^ a b Crowther, Andrew. The Life of W. S. Gilbert. The Gilbert and Sullivan archive at Boise State University, Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Stedman (1996), pp. 26-29, 123-4, and the introduction to Gilbert's Foggerty's Fairy and Other Tales.

- ^ Bond, Jessie. The Reminiscenes of Jessie Bond: Introduction. The Gilbert and Sullivan archive at Boise State University, Retrieved on 2007-05-21. Bond created the mezzo-soprano roles in most of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and is here leading in to a description of Gilbert's role reforming the Victorian theatre.

- ^ Stedman (1996) pp 62-68; Bond, Jessie, The Reminiscenes of Jessie Bond: Introduction. The Gilbert and Sullivan archive at Boise State University, Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Crowther, Andrew. Ages Ago — Early Days. The Gilbert and Sullivan archive at Boise State University, Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Interview by Arthur H. Lawrence, Part 1, The Strand Magazine, Volume xiv, No.84 (December 1897) See also Sullivan's Letter to The Times, Oct. 27 1881, Issue 30336, pg. 8 col C

- ^ Description and analysis of Sullivan's early orchestral works

- ^ Stephen Turnbull's Biography of W. S. Gilbert at the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive. Downloaded 22 November 2006

- ^ Tillett, Selwyn and Spencer, Roderic (2002). "Forty Years of Thespis Scholarship". (PDF). Chimes Musical Theatre. Retrieved on 2007-05-21

- ^ Jean-Bernard Piat: Guide du mélomane averti, Le Livre de Poche 8026, Paris 1992.

- ^ Thespis or The Gods Grown Old. The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive at Boise State University. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Walbrook, H. M. (1922), Gilbert and Sullivan Opera, a History and Comment (Chapter 3). The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive at Boise State University. Retrieved on 2007-05-21. See also Barker, John W. "Gilbert and Sullivan", Madison Savoyards, Ltd. Retrieved on 2007-05-21, which quotes Sullivan's recollection of Gilbert reading the libretto of Trial by Jury to him: "As soon as he had come to the last word he closed up the manuscript violently, apparently unconscious of the fact that he had achieved his purpose so far as I was concerned, in as much as I was screaming with laughter the whole time."

- ^ The Sorcerer. The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive at Boise State University. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Rosen, Zvi S. The Twilight of the Opera Pirates: A Prehistory of the Right of Public Performance for Musical Compositions. Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal, Vol. 24, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Savoy Theatre, The Strand, WC2. arthurlloyd.co.uk. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Bradley (1996), p. 176.

- ^ The Gondoliers. The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive at Boise State University. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ a b Crowther, Andrew.The Carpet Quarrel Explained. The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive at Boise State University. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Gilbert's Plays. The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive at Boise State University. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Wolfson, p. 7.

- ^ Wolfson, passim

- ^ Wolfson, pp. 61-65.

- ^ [Bradley, Ian C. Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan Oxford University Press (2005), Chapter 1. ISBN 0195167007

- ^ a b c Green, Edward. "Ballads, songs, and speeches" (sic). BBC, 20 September 2004. Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ Lawrence, Arthur H. "An illustrated interview with Sir Arthur Sullivan" Part 3, from The Strand Magazine, Vol. xiv, No.84 (December 1897). Retrieved on 2007-05-21.

- ^ [Bradley, Ian C. Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan Oxford University Press (2005), p. 9. ISBN 0195167007

- ^ Sporting stripes set Rehnquist apart, Sept. 4, 2005, Journal Sentinel Online. Downloaded 26 May 2007.

- ^ including Crowther, Stedman, Bailey, Bradley, Ainger, and Jacobs

- ^ The New Penguin Opera Guide, ed. Amanda Holden, Penguin Books, London 2001 and The Penguin Concise Guide to Opera, ed. Amanda Holden, Penguin Books, London 2005 both note: "Operetta is the internationally recognized term for the type of work on which William Schwenck Gilbert and Sullivan collaborated under Richard D'Oyly Carte's management (1875-96), but they themselves used the words 'comic opera'". See also the Oxford Dictionary of Opera, ed. John Warrack and Ewan West, Oxford University Press 1992 and the The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, 4 vols, ed. Stanley Sadie, Macmillan, New York 1992

References

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan, a Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Allen, Reginald (1975). The First Night Gilbert and Sullivan. London: Chappell & Co. Ltd.

- Baily, Leslie (1966). The Gilbert and Sullivan Book (new ed. ed.). London: Spring Books.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Benford, Harry (1999). The Gilbert & Sullivan Lexicon, 3rd Revised Edition. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Queensbury Press. ISBN 0-9667916-1-4

- Bradley, Ian (1996). The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Cellier, François and Cunningham Bridgeman (1914). Gilbert and Sullivan and Their Operas. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & sons, ltd. This book is available online here.

- Fitzgerald, Percy Hetherington (1899). The Savoy Opera and the Savoyards. London: Chatto & Windus. This book is available online here.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1994). The Savoy Operas. Hertfordshire, England: Wordsworth Editions Ltd.

- Williamson, Audrey (1953). Gilbert and Sullivan Opera. London: Marion Boyars.

- Wolfson, John (1976). Final curtain: The last Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. London: Chappell in association with A. Deutsch. ISBN 0-903443-12-0

Further reading

- Gilbert, W. S. (1932). Deems Taylor, ed. (ed.). Plays and Poems of W. S. Gilbert. New York: Random House.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Gilbert, W. S. (1976). The Complete Plays of Gilbert and Sullivan. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1992). Arthur Sullivan – A Victorian Musician (Second Edition ed.). Portland, OR: Amadeus Press.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

External links

- General

- The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

- Description of the G&S partnership

- Historical survey of G&S

- Savoynet - an email-based G&S listserv

- Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte

- A list of "G&S Derived Works" with links to more information

- Gilbert & Sullivan song parodies

- Article on G&S's leading ladies

- Chronology of Gilbert and Sullivan

- Music

- G&S Archive MIDI homepage

- The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography

- MP3 files of music from The Pirates of Penzance 2002 performance by The Manchester University Gilbert & Sullivan Society

- MP3 files of music from The Mikado 1998 performance by The Manchester University Gilbert & Sullivan Society

- Appreciation societies

- The Gilbert and Sullivan Society, London

- The Manchester Gilbert and Sullivan Society

- The New England Gilbert and Sullivan Society (includes links to other North American societies)

- The Gilbert and Sullivan Society of New York

- Performing groups

- G&S Archive "Performing Groups" page Comprehensive listing of performing companies.