United Ireland

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. |

A politically United Ireland is the common goal of Irish republicans and Irish nationalists, envisaging that the island of Ireland (currently divided into the Republic of Ireland, a sovereign state, and Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom) be united as a single and independent political entity. Many different models for unification have been suggested including federalism[1] and joint sovereignty, as well as a unitary state. Nearly all Irish Republican organizations promote some form of socialism as the system that would be practiced by a united Irish governing body.

Since the English Tudor re-conquest of Ireland in the mid-16th century, a series of measures, both administrative and militaristic, were brought in to deal with Irish resistance to the English administration based at Dublin Castle. These were met with centuries of opposition and political violence. In 1920 the island was partitioned into what would become the Republic of Ireland, where opinion is almost uniformly in favour of independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland [2], and Northern Ireland, where the population is divided 60:40 in favour of remaining within the United Kingdom[citation needed].

During the 20th century, political violence continued in Northern Ireland, but was virtually unheard of in the Republic. However, in the Republic reunification of the island remains an important political ambition, though one pursued through constitutional means. In Northern Ireland, reunification is a goal of Nationalist political parties and of Irish republlican paramilitary groups. Resistance to a united Ireland is, conversely, a goal of Unionist political parties and of loyalist paramilitary groups.

History

Kings and High Kings

Before the coming of the Normans there existed the title of Ard Rí (High King), usually held by the Uí Néill but this was more of a ceremonial title denoting a sort of "first among equals" rather than an absolute monarchy as developed in England and Scotland. Nevertheless, several strong characters imbued the office with real power, most notably Máel Sechnaill mac Maíl Ruanaid (845-860), his son Flann Sinna (877-914) and Flann's great-grandson Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill (979-1002; 1014-1022), Brian Boru (1002-1014), Muircheartach Ua Briain (1101-1119), and Toirdhealbhach Ua Conchobhair (1119-1156).

What prevented the consolidation of truly national power even by the Ard Ríanna was the fact that the island was divided into a number of autonomous, fully independent kingdoms ruled by rival dynasties. The most powerful of these kingdoms in the immediate pre-Norman era were Aileach, Brefine, Mide, Leinster, Osraige, Munster and Connacht. In addition to these, there were a number of lesser subject kingdoms such as Airgialla, Uladh, Brega, Dublin, Ui Failghe, Laois, Desmond, and Hy-Many. Many of these kingdoms and lordships retained, at the very least, some degree of independence right up to the end of independent Gaelic polity in the 17th century.

Confederate Ireland 1642-1649

The next significant moment occurred in 1642 when the Confederate Catholics Association of Ireland – an Irish Catholic government formed to fight the Irish Confederate Wars, assembled at Kilkenny and held an all-Ireland assembly. The Confederates did rule much of Ireland up to 1649, but were riven by dissent and civil war in later years over whether to ally themselves with the English Royalists in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Ultimately, they dissolved their Association in favour of unity with the Royalists, but were defeated anyway in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.

1653-1921

Although ruled by Britain, Ireland was a united political entity from the end of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in 1653 until 1921 .

Until the Constitution of 1782, Ireland was placed under the effective control of the British-appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland due to restrictive measures such as Poynings Law. From 1541 to 1801, the island's political status was of a Kingdom of Ireland in personal union with the English (and later the British) Crown. Under the leadership of Henry Grattan, the Irish parliament (still dominated by the Ascendancy) acquired a measure of autonomy for a time. After the Act of Union, Ireland became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, a single entity ruled by the Parliament at Westminster.

Ireland was last undivided at the outbreak of World War I after national self-government in the form of the Third Home Rule Act 1914, won by John Redmond leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party was placed on the statute books, but suspended until the end of the war. It was amended to partition Ireland following the objections of Irish Unionists.

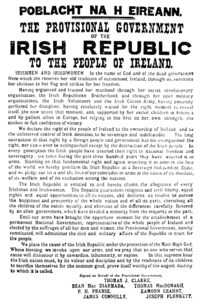

In the 1918 general election, the republican Sinn Féin political party won a landslide victory. The newly elected Sinn Féin candidates formed a republican assembly Dáil Eireann which unilaterally declared itself in 1919 the Government of the Irish Republic and independent of the British Empire. Its claims over the entire island were, however, not accepted by northern Unionists. Under the Anglo-Irish Treaty the Irish Free State became in 1922 the name of the state covering twenty-six counties in the south and west, replacing the Irish Republic, while six counties in the northeast remained within the United Kingdom under the 1920 Government of Ireland Act. According to some historians, Sinn Féin had no special policy towards Ulster despite its different religious and political make-up, regarding it as an integral part of an Irish republic.

1922-1998

The Free State and its successor, the Republic of Ireland (declared in 1949) both claimed that Northern Ireland was part of their territory, but did not attempt to force reunification, nor did they claim to be able to legislate for it. In 1998, following the Belfast Agreement, the Republic voted to amend Articles 2 and 3 of its constitution so that the territorial claim was amended with a recognition of the Northern Ireland people's right to self-determination.

Present day

The leading political parties in the Republic of Ireland, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, have often made a united Ireland a part of their political message. It is also a main focus of Sinn Féin and Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) in Northern Ireland.

In contrast, the Unionist community – composed primarily of Protestants in the six counties that form Northern Ireland – opposes unification. All of the island's political parties (except for tiny fringe groups with little electoral representation) have accepted the principle of consent, which states that Northern Ireland's constitutional status cannot change without majority support in Northern Ireland.

Many Protestants in Northern Ireland argue they have a distinct identity that would be overwhelmed in a united Ireland. They cite the decline of the small Protestant population of the Republic of Ireland since secession from the United Kingdom, the economic cost of unification, their place in a key international player (within the UK) and their (Protestants) mainly non-Irish ancestry. Unionist people in Northern Ireland primarily find their cultural and ethnic identity from the Scottish and English planters, whose descendants can also be found in the three counties of Ulster which are governed by the Republic of Ireland. Such individuals celebrate their Scots heritage each year like their counterparts in the other six counties. While Catholics in general consider themselves to be Irish, Protestants generally see themselves as British, as shown by several studies and surveys performed between 1971 and 2006. [3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]. Many Protestants do not consider identify themselves as primarily Irish, as many Irish nationalists do, but rather within the context of an Ulster or British identity. A 1999 survey showed that a little over half of Protestants felt "Not at all Irish.", while the rest "felt Irish" in varying degrees.[11]

Some have suggested that one such method of governing in a United Ireland, would be for a united nine-county Ulster to have local self-government, and perhaps local self-government for Ireland's other three provinces (like U.S. states or German federal states), to help ease the worries Unionists in Ulster might have about joining a reunified all-island nation-state.

Given that all significant political parties and both the UK and Irish Governments support the "Principle of Consent" the final choice is one for the people of Northern Ireland, alone, to decide. Meanwhile it should be pointed out that in certain instances there does in fact exist a degree of Irish unity already. For example the Church of Ireland and the Roman Catholic Church are both organised on an all Ireland basis. Also the Irish rugby football and cricket teams are drawn from both north and south. Soldiers from Irish regiments in the British army are also drawn from both north and south.

Currently, both the Irish and British governments are creating a number of all-island bodies and services, such as the all-island electricity network from November 2007, then to be followed by the all-island gas network. [12] Not only services, but also governmental bodies such as The Loughs Agency, Waterways Ireland, InterTradeIreland and, most notably, the North/South Ministerial Council, have been set up; with more planned in the near future. [13] Recently, politicians have called for there to be an all-island corporation tax of 12.5% (currently the Republic's corporation tax - the lowest in the EU), in order to boost Northern Ireland's economy.[14] Other politicians have called for an all-island telecommunications network, especially within regard to mobile phones. [15] The Irish government are currently investing over €1 billion in Northern Ireland as well, especially in the West, around Derry. Investments include upgrading City of Derry airport (at a cost of €11 million), building a Letterkenny/Derry-Dublin motorway or high-quality dual carriageway, reopening the Ulster Canal, and improving cancer services in the region for those in the region itself, but also people from County Donegal in the Republic. [16]

Many in Ireland feel that these moves are steps heading towards eventual unification, but also helping to improve the quality of life for people throughout the island in the meantime. If unification does occur, then the greater degree of integration and co-operation at present would mean that the economy would not suffer as a result.

Public opinion in Northern Ireland

A possible referendum on a united Ireland was included as part of the terms of the Good Friday Agreement. Currently about 42% of the Northern Ireland electorate vote for Irish nationalist parties that oppose the union with Great Britain and support a united Ireland as an alternative, although it is not the only issue at election time so it is difficult to take this figure as a direct indication of levels of support for a united Ireland. A survey taken in 2006[17] shows support for a united Ireland at 30% and support for Northern Ireland remaining in the United Kingdom at 54%. 4% support independence or other arrangements.

Public opinion in the Republic of Ireland

Support for Irish unity is a feature of all major political parties in the Republic of Ireland. Some very small pressure groups do exist, such as the Reform Movement and lodges of the Orange Order in the Republic of Ireland, that are sympathetic to Northern Ireland remaining within the UK for the foreseeable future, but their impact on the broader political opinion is negligible. A 2006 Sunday Business Post survey[18] reported that 77% of voters in the Republic favour a united Ireland: 22% believe that "achieving a united Ireland should be the first priority of the government" while 55% say they "would like to see a united Ireland, but not as the first priority of government." Of the remainder 10% said no efforts should be made to bring about a united Ireland and 13% had no opinion.

This poll was markedly up from one year earlier when a Sunday Independent article[19] that reported that 55% would support a united Ireland, while the remainder such an ambition held no interest.

Public opinion in Great Britain

There is significant support in Great Britain for Ireland to reunify as a political entity. An ICM poll conduced by The Guardian in 2001 revealed that only 26% of Britons supported Northern Ireland remaining a part of the UK, while 41% supported a united Ireland.[20] The British Social Attitudes Survey in 2004 found 32% supported Northern Ireland remaining part of the UK, and 45% supported a united Ireland.[21]

Political support and opposition for unification

Northern Ireland

Opposition to reunification comes mainly from Unionist political parties in Northern Ireland, particularly the Ulster Unionist Party and the Democratic Unionist Party. It also comes from loyalist paramilitary groups such as the Ulster Defence Association and Ulster Volunteer Force.

Nationalist parties

Nationalist parties in Northern Ireland support the independence of Northern Ireland (and of Ireland as a whole) from the United Kingdom and all nationalist parties support a united Ireland in some form. Sinn Féin is currently the largest nationalist party in the Northern Ireland Assembly (and the fifth largest in the Republic's Dáil.)[22] Until recently, it had a policy of violent intervention through the Provisional Irish Republican Army but since the mid-90's had adopted a policy of achieving a united Ireland through constitutional means only. It supports integration of political institutions across the island of Ireland. For example, the party has proposed that Northern Ireland should have some form of representation in the Dáil, with elected representatives from either the Stormont or Westminster parliaments able to participate in debates, if not vote. The major parties in the Republic have rejected this notion on a number of occasions. Should Irish reunification ever occur, Sinn Féin has stated that it would wish to amend the Irish constitution to protect minorities, including the Protestant and Ulster Scots communities.

The Social Democratic and Labour Party had previously been the largest nationalist party in Northern Ireland, but has suffered in elections since Sinn Féin's abandoned armed politics. As with Sinn Féin, it is committed to achieving a united Ireland. However, throughout its history, it has believed that reunification should be accomplished through constitutional means only. It would support a united Ireland only if a majority of both parts of Ireland voted for it in a referendum. In a united Ireland, the SDLP would support the continuation of a devolved Northern Ireland, governed by a local assembly.

Minor Nationalist parties

Aside from the major parties, Northern Ireland has several minor Nationalist parties. Among these, some parties are tied to paramilitary organisations and seek the reunification of Ireland through armed politics. These include the Irish Republican Socialist Party, which supports a united socialist Irish state and is affiliated with the Irish National Liberation Army. Another such party, Republican Sinn Féin, linked to the Continuity IRA, does not believe that the Irish government or the Northern Ireland Executive are legitimate as neither legislates for Ireland as a whole. Its Éire Nua (in English, New Ireland) policy advocates a unified federal state with regional governments for the four provinces and the national capital in Athlone, a town in the geographic centre of Ireland. None of these parties has significant electoral support.

Republic of Ireland

Major parties

The largest party in the Republic, and current governing party (through a coalition), is Fianna Fáil. It has supported reunification since its foundation, when it split from Sinn Féin in 1926 in protest at the party's policy of refusal to accept the legitimacy of the partitioned Irish state. However, in its history since, it has differed on how to accomplish it. Fianna Fáil rejected the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, which gave the Republic of Ireland an advisory role in Northern Ireland, claimed the agreement was in conflict with the then Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution of Ireland because it recognised Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom. It later oversaw the removal of these articles from the constitution and today fully supports the Good Friday Agreement, which it negotiated in coalition with the Progressive Democrate (see below).

The second-largest party, Fine Gael (whose English name is the United Ireland Party) a descendent of the pro-Anglo-Irish Treaty section of Sinn Féin upon the partition of Ireland, has also supported reunification as one of the its key aims since its foundation. It supports the Good Friday Agreement and had previously negotiated the Anglo-Irish agreement.

The Labour Party, likewise, has also supported reunification since the foundation of the state, although it has always considered this aim secondary to social causes. It also fully supports the Good Friday Agreement, and supported the Anglo-Irish agreement. The former President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, resigned from the Irish Labour Party because she objected to the exclusion of unionists from the talks that led to the 1985 agreement.

Minor parties

The Progressive Democrats, a liberal party, which split from Fianna Fáil in the mid-80's, have supported reunification since its foundation, but only when a majority of the people of Northern Ireland consent to it. The party fully supports the Good Friday Agreement. Former party leader, Mary Harney, was expelled from Fianna Fáil for supporting the Anglo-Irish agreement. The party was one of the key negotiators of the Good Friday Agreement.

The Green Party support the full implementation of the Good Friday Agreement, which takes the possibility of Irish unification into account as the basis of simultaneous referendums on the issue being successful in the Republic and in Northern Ireland. The Green Party are all all-island party, having TDs in the Republic and an MLA in the North. The Green Party are the first all-Ireland party to be in power in the Dáil, as of 14 June, 2007.

Sinn Féin is also an active party in the Republic, where its policies towards a united Ireland are the same as in Northern Ireland.

Great Britain

In Great Britain all major parties support the Belfast Agreement. Right-wing groups tend to be Unionist in outlook. Left-wing and liberal groups have traditionally been more open to a united Ireland.

Major Parties

Historically there has been strong support for a United Ireland within the Left of the Labour Party, and in the 1980s it became official policy to support a united Ireland by consent.[23] The policy of "unity by consent" continued into the 1990s, eventually being replaced by a policy of neutrality in line with the Downing Street Declaration.[24]

The Conservative Party has traditionally taken a strongly unionist line in relation to the United Kingdom as a whole by opposing nationalism in Scotland and Wales as well as Northern Ireland. Until 1974 they had a parliamentary alliance with the Ulster Unionist Party and the two parties retained formal ties until 1985. The Conservatives current position is to "[work] in Northern Ireland to restore stable and accountable government based on all parties accepting the principles of democracy and the rule of law."[25]

The Liberal Democrats have a close relation with the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland and share their policy of supporting the Belfast Agreement whilst expressing reservations about what they perceive as its institutionalised sectarianism.

Economic consequences of Irish unification

Historically Northern Ireland has been the poorest part of the United Kingdom, although in recent years it has experienced stronger Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth than the UK average [4] and GDP per capita is now higher than Wales and North East England. As of 2004, the GDP per capita of the Republic of Ireland is €30,414 (141% of the EU-27 average) while in Northern Ireland it is €21,292 (99% of the EU-27 average) [5]. A simple calculation using 2004 GDP and population estimates gives a GDP per capita of €27,790 for the whole of Ireland (9% less than that that of the Republic of Ireland). The structural costs of unification are difficult to quantify but are likely to be proportionately less than that of German reunification due to the greater degree of economic integration that exists between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.[citation needed]

See also

- 1918 election

- Nationalism

- Partition of Ireland

- Repartition of Ireland

- Irish nationalism

- Unionism (Ireland)

- Demographics and politics of Northern Ireland

- Provisional Irish Republican Army

- Scottish independence

- Welsh nationalism

- Cornish self-government movement

- English nationalism

References

- ^ http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/politics/docs/sf/ga011186.htm

- ^ http://www.breakingnews.ie/2006/04/02/story252182.html

- ^ Breen, R., Devine, P. and Dowds, L. (editors), 1996. "Social Attitudes in Northern Ireland: The Fifth Report" ISBN 0-86281-593-2. Chapter 2 retrieved from http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/othelem/research/nisas/rep5c2.htm on August 24, 2006. Summary: In 1989—1994, 79% Protestants replied "British" or "Ulster", 60% of Catholics replied "Irish."

- ^ Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, 1999. Module:Community Relations. Variable:NINATID. Summary:72% of Protestants replied "British". 68% of Catholics replied "Irish".

- ^ Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey. Module:Community Relations. Variable:BRITISH. Summary: 78% of Protestants replied "Strongly British."

- ^ Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, 1999. Module:Community Relations. Variable:IRISH. Summary: 77% of Catholics replied "Strongly Irish."

- ^ Institute of Governance, 2006. "National identities in the UK: do they matter?" Briefing No. 16, January 2006. Retrieved from http://www.institute-of-governance.org/forum/Leverhulme/briefing_pdfs/IoG_Briefing_16.pdf on August 24, 2006. Extract:"Three-quarters of Northern Ireland’s Protestants regard themselves as British, but only 12 per cent of Northern Ireland’s Catholics do so. Conversely, a majority of Catholics (65%) regard themselves as Irish, whilst very few Protestants (5%) do likewise. Very few Catholics (1%) compared to Protestants (19%) claim an Ulster identity but a Northern Irish identity is shared in broadly equal measure across religious traditions."Details from attitude surveys are in Demographics and politics of Northern Ireland.

- ^ [1] University of York Research Project 2002-2003 L219252024 - Public Attitudes to Devolution and National Identity in Northern Ireland

- ^ [2] Northern Ireland: Constitutional Proposals and the Problem of Identity, by J. R. Archer The Review of Politics, 1978

- ^ [3] A changed Irish nationalism? The significance of the Belfast Agreement of 1998, by Joseph Ruane and Jennifer Todd

- ^ Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, 1999. Module:Community Relations. Variable:IRISH.

- ^ BreakingNews.ie - 'All Island Gas Plans Welcomed'

- ^ Irish Government - 'North / South Institutions'

- ^ Irish Times - 'Paisley urges lower corporation tax'

- ^ BreakingNews.ie - 'SF calls for single Irish phone tariff'

- ^ [Fianna Fáil 2007 Election manifesto - 'Peace and Unity]

- ^ NI Life and Times Survey 2006, "2006 Do you think the long-term policy for Northern Ireland should be for it …"

- ^ "ThePost.ie - "Majority want a nation once again"", Breaking News.ie, 2 April 2006

- ^ Jerome Reilly, "Almost half of us would reject united Ireland: poll", Sunday September 18 2005

- ^ Jonathan Freedland, "Surge in support for Irish unity" The Guardian, Tuesday August 21, 2001

- ^ "NIRELAND by YEAR". British Social Attitudes Survey. 2004. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ See: Irish general election, 2007

- ^ "The New Hope For Britain". Labour Party. 1983. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ "Britain will be better with new Labour". Labour Party. 1997. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ "Built to Last: The Aims and Values of the Conservative Party" (PDF). Conservative Party. 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-12.