Barn swallow

| Barn Swallow | |

|---|---|

| |

| European subspecies, H. r. rustica in Denmark | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. rustica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hirundo rustica Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| |

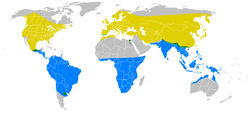

| Yellow: breeding range Green: resident year-round Blue: non-breeding range | |

The Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) is the most widespread species of swallow.[2] A distinctive passerine bird possessing blue upperparts, a long, deeply forked tail and curved, pointed wings, it occurs in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas.[2] It is often just called Swallow in northern Europe, where it is the only common member of the swallow family. The scientific name derives from two Latin words: hirundo meaning "swallow" and rusticus meaning "of the country".[3]

There are six subspecies of the Barn Swallow breeding across the Northern Hemisphere. Four are strongly migratory, and their wintering grounds cover much of the Southern Hemisphere down to northern Australia. Its huge range means that the Barn Swallow is not endangered, although there may be local population growth or decline, or specific threats such a the construction of an international airport in South Africa.[4]

The Barn Swallow is a bird of open country which normally uses man-made structures to breed, and consequently has spread with human expansion. There are frequent cultural references in literary and religious works due to its living in close proximity to humans and its annual migration. It builds a cup nest from mud pellets in barns or similar structures, and feeds on insects caught on the wing. The appearance and beneficial habits of this species mean that is tolerated by the humans with whom it lives so closely, and this acceptance was reinforced in the past by superstitions regarding the bird and its nest.

Description

The adult male of the nominate European subspecies H. r. rustica is 17–19 centimetres (6.7-7.5 in) long including 2–7 centimetres (0.8-2.8 in) of elongated outer tail feathers. It has a wingspan of 32–34.5 centimetres (12.6-13.6 in) and weighs 16–22 grammes (0.56-0.78 oz). It has steel blue upperparts and a rufous forehead, chin and throat, separated from the off-white underparts by a broad dark blue-black breast band. The outer tail feathers are elongated, giving the distinctive deeply-forked "swallow tail". There is a line of white spots across the outer end of the upper tail.[5]

The female is similar to the male, but the tail streamers are shorter, the blue of the upperparts and breast band is less glossy, and the underparts are paler. The juvenile is browner, has a paler rufous face and whiter underparts. It also lacks the long tail streamers of the adult.[2]

The song of the Barn Swallow is a cheerful warble, often ending with su-seer, the second note higher than the first, but falling in pitch. Calls include witt or witt-witt, and a loud splee-plink when excited.[5] The alarm calls include a sharp siflitt for predators like cats, and a flitt-flitt for birds of prey like the Hobby.[6] This species is fairly quiet on the wintering grounds.[7]

The distinctive combination of a red face and blue breast band make the adult Barn Swallow readily separable from the African Hirundo species, and from the Welcome Swallow (Hirundo neoxena) with which its range overlaps in Australasia. In Africa the short tail streamers of the juvenile Barn Swallow invite confusion with juvenile Red-chested Swallow, but the latter has a narrower breast band and more white in the tail.[8]

Taxonomy

The Barn Swallow was described by Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae in 1758 under the genus Hirundo.[9] This the only member of that genus to have a breeding range extending into the New World, the majority of Hirundo species being native to Africa. This genus of blue-backed swallows is sometimes called the "barn swallows".[2]

There are few taxonomic problems within the genus, but the Red-chested Swallow (Hirundo lucida), a resident of West Africa, the Congo basin and Ethiopia, was formerly considered as a subspecies of Barn Swallow. The Red-chested Swallow is slightly smaller than its migratory relative, has a narrower blue breast-band, and the adult has shorter tail streamers. In flight, it also looks paler underneath than Barn Swallow.[8]

Subspecies

Six subspecies of Barn Swallow are considered in this article. In eastern Asia, a number of additional or alternative forms have been proposed, including saturata by Robert Ridgway in 1883,[10] kamtschatica by Benedykt Dybowski in 1883,[11] and mandschurica by Wilhelm Meise in 1934.[10] Given the uncertainties over the validity of these forms,[11] this article follows the treatment of Turner and Rose.[2]

- H. r. rustica, the nominate European subspecies, breeds in Europe and Asia, as far north as the Arctic Circle, south to North Africa, the Middle East and Sikkim, and east to the Yenisei River. It migrates on a broad front to winter in Africa, Arabia, and the Indian subcontinent.[2]

- H. r. transitiva was described by Ernst Hartert in 1910.[10] It breeds in the Middle East from southern Turkey to Israel and is partially resident, but some birds winter in East Africa. It has orange red underparts and a broken breast band.[2]

- H. r. savignii, the resident Egyptian subspecies, was described by James Stephens in 1817.[12] It resembles transitiva, which also has orange-red underparts, but savignii has a complete broad breast band and deeper red hue to the underparts.[6]

- H. r. gutturalis, described by Giovanni Antonio Scopoli in 1786,[10] has whitish underparts and a broken breast band. It breeds from the eastern Himalayas to Japan and Korea. It winters across tropical Asia from India and Sri Lanka east to Indonesia and New Guinea. Increasing numbers are wintering in Australia. It hybridises with H. r. tytleri in the Amur area. It is thought that the two eastern Asia forms were once geographically separate, but the nest sites provided by expanding human habitation allowed the ranges to overlap.[2] H. r. gutturalis is a vagrant to Alaska and Washington,[13] but is easily distinguished from the breeding subspecies there, which has reddish underparts.[2]

- H. r. tytleri, first described by Thomas Jerdon in 1864,[10] has deep orange-red underparts and an incomplete breast band. It breeds in central Siberia south to northern Mongolia and winters from eastern Bengal east to Thailand and Malaysia.[2]

- The North American subspecies H. r. erythrogaster, described by Pieter Boddaert in 1783,[10] differs from the European subspecies in having redder underparts and a narrower, often incomplete, blue breast band. It breeds throughout North America, from Alaska to southern Mexico, migrating to the Lesser Antilles, Costa Rica, Panama and South America to winter.[7] A few may winter in the southernmost parts of the breeding range. This subspecies funnels through Central America on a narrow front, being abundant on passage in the lowlands of both coasts.[14]

Unexpectedly, DNA analyses show that Barn Swallows from North America colonised the Baikal region of Siberia, a dispersal direction opposite to that for most changes in distribution between North America and Eurasia. [15]

Behaviour

Habitat

The preferred habitat of the Barn Swallow is open country with low vegetation, such as pasture, meadows and farmland, and preferably near water, but it avoids heavily wooded or precipitous areas and densely built-up locations. The presence of accessible open structures such as barns to provide breeding sites, and exposed locations such as wires, roof ridges or bare branches for perching, are also important in the breeding range.[5]

In winter, the Barn Swallow is cosmopolitan in its choice of habitat, avoiding only dense forests. It has been recorded as breeding in the more temperate parts of its winter range, such as the mountains of Thailand.[16][17]

Feeding

The Barn Swallow is similar in its habits to other aerial insectivores, including other swallow species and the unrelated swifts. It is not a particularly fast flier, with a speed estimated at about 11 m/s (36 ft/s),[18] and a wing beat rate of approximately 7-9 times each second,[18] but it has the manoeuvrability necessary to feed on flying insects while airborne. It is often seen flying relatively low in open or semi-open areas.

It typically feeds 7-8 metres (23-26 ft) above shallow water or the ground, often following animals, humans or farm machinery to catch disturbed insects, but it will occasionally pick prey items from the water surface, walls and plants. In the breeding areas, large flies make up around 70% of the diet, with aphids also a significant component. However, in Europe, The Barn Swallow takes fewer aphids than the House or Sand Martins.[5] On the wintering grounds, Hymenoptera, especially flying ants are important food items. When egg-laying, Barn Swallows hunt in pairs, but will form often large flocks otherwise.[2] The Barn Swallow drinks by skimming low over lakes or rivers and scooping up water with its open mouth.[19]

Swallows gather in communal roosts after breeding, sometimes thousands strong. Reedbeds are regularly favoured, the birds swirling en masse before swooping low over the reeds.[6] Reed beds are an important source of food prior to and whilst on migration; although the Barn Swallow is a diurnal migrant which can feed on the wing whilst it travels low over ground or water, the reed beds enable fat deposits to be established or replenished.[20]

Breeding

The male Barn Swallow returns to the breeding grounds first and selects a nest site, which is then advertised to females with a circling flight and song. The breeding success of the male is related to the length of the tail streamers, longer streamers being more attractive to the female.[5][21] Males with longer tail feathers are, on average, longer-lived and more disease resistant, and females therefore gain an indirect fitness benefit from this form of selection, since longer tail feathers indicate a genetically stronger individual which will produce offspring with enhanced vitality.[22]

Males with long streamers also have larger white tail spots, and since feather-eating bird lice prefer white feathers, large white tail spots without parasite damage again demonstrate breeding quality; there is a positive association between spot size and the number of offspring produced each season.[23]

Both sexes defend the nest, but the male is particularly aggressive and territorial.[2] Once established, pairs stay together to breed for life, but extra-pair copulations are common, making this species genetically polygamous, despite being socially monogamous.[24] Males guard females actively to avoid being cuckolded.[25] Males may use deceptive alarm calls to disrupt extrapair copulation attempts toward their mates.[26]

The Barn Swallow, as its name implies, typically nests inside accessible buildings such as barns and stables, or under bridges and wharves. The neat cup-shaped nest is placed on a beam or against a suitable vertical projection. It is constructed by both sexes (although more by the female) with mud pellets collected in their beaks, and lined with grasses, feathers or other soft materials.[2] Barn Swallows may nest colonially where sufficient high-quality nest sites are available, and within a colony, each pair defends a territory around the nest, which, for the European subspecies, is four to eight m2 in size. Colonies tend to be larger in North America.[19]

In North America at least, Barn Swallows frequently engage in a symbiotic relationship with Ospreys. Barn Swallows will build their nest below an Osprey nest, receiving protection from other birds of prey which are repelled by the (exclusively fish-eating) Ospreys. The Ospreys are alerted to the presence of these predators by the alarm calls of the Swallows.[19]

Before man-made sites became common, the Barn Swallow nested on cliff faces or in caves, but this is now rare. The female lays two to seven, but typically four or five, reddish-spotted white eggs. The eggs are 20 x 14 millimetres (0.06 x 0.08 in) in size, and weigh 1.9 grammes (0.07 oz), of which 5 percent is shell. In Europe, the female does almost all the incubation, but in North America the male may incubate up to 25% of the time. The incubation period is normally 14–19 days, with another 18–23 days before the altricial chicks fledge. The fledged young stay with, and are fed by, the parents for about a week after leaving the nest. Occasionally, first-year birds from the first brood will assist in feeding the second brood.[2]

The Barn Swallow will mob intruders such as cats or accipiters that venture too close their nest, often flying very close to the threat.[22] Adult Barn Swallows have few predators, but some are taken by accipiters, falcons, and owls. Brood parasitism by cowbirds in North America or cuckoos in Eurasia is rare.[19][5]

There are normally two broods, the nest being reused for the second brood, and repaired and reused in subsequent years. Hatching success is 90%, and fledging 70-90%. Average mortality is 70-80% in the first year and 40-70% for the adult. Although the record age is more than 11 years, most survive less than four years.[2]

The Barn Swallow has been recorded as hybridising with Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) and Cave Swallow (P. fulva) in North America, and House Martin (Delichon urbicum) in Eurasia, the cross with the latter being one of the most common passerine hybrids.[22]·

Status

The Barn Swallow has an enormous range, with an estimated global extent of 10 million km² and a population of 190 million individuals. Although global population trends have not been quantified, the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e. declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations). For these reasons, the species is evaluated as "least concern" on the 2007 IUCN Red List,[1] and has no special status under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) which regulates international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants.[19]

This is a species which has greatly benefited historically from forest clearance, which has created the open habitats it prefers, and from human habitation which have given it an abundance of safe man-made nest sites. There have been local declines through DDT in Israel in the 1950s, competition for nest sites with House Sparrows in the US in the 19th century, and an ongoing gradual decline in numbers in parts of Europe and Asia due to agricultural intensification reducing the availability of insect food. However, there has been an increase in the population in North America during the 20th century with the greater availability of nesting sites, and range expansion, including the colonisation of northern Alberta.[2]

A specific threat to wintering birds from the European populations is the transformation by the South African government of a light aircraft runway near Durban into an international airport for the 2010 FIFA World Cup. The roughly 250 metres (275 yards) square Mount Moreland reed bed is a night roost for more than three million Barn Swallows, which represent one percent of the global population and eight percent of the European breeding population. The reed bed lies on the flight path of aircraft using the proposed La Mercy airport and there were fears that it would be cleared because the birds could threaten aircraft safety.[4][27] However, advanced radar technology will be installed to enable planes using the airport to be warned of bird movements, and if necessary take appropriate measures to avoid the flocks.[28]

Relationship with humans

The Barn Swallow is an attractive bird which feeds on flying insects, and has therefore been tolerated by humans when it shares their buildings for nesting. As one of the earlier migrants, this conspicuous species is also seen as an early sign of summer's approach.

In the Old World, the Barn Swallow appears to have used man-made structures and bridges since time immemorial.[29] An early reference is in Virgil's Georgics (29 BC) ...garrula quam tignis nidum suspendat hirundo (...the twittering swallow hangs its nest from the rafters).[30]

It is believed that the Barn Swallow began attaching its nest to Native American habitations in the early 1800s, and the subsequent spread of humans across North America is thought to have resulted in a dramatic population expansion of the species across that continent.[15]

In literature

Many literary references are based on the Barn Swallow's northward migration as a symbol of spring or summer. The proverb about the necessity for more than one piece of evidence goes back at least to Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: "For as one swallow or one day does not make a spring, so one day or a short time does not make a fortunate or happy man."[31]

The Barn Swallow symbolizes the coming of spring and thus love in the Pervigilium Veneris, a late Latin poem. T. S. Eliot, in "The Waste Land", quoted the line "Quando fiam uti chelidon [ut tacere desinam]?" ("When will I be like the swallow, so that I can stop being silent?") This refers to a version of the myth of Philomela in which she turns into a swallow and her sister Procne into a Nightingale; in more familiar versions, the two species are reversed.[32] On the other hand, an image of the assembly of Swallows for their southward migration concludes John Keats's ode "To Autumn".

There are mentions of the Barn Swallow in the Bible, although it seems likely that it is confused with the swifts in many translations,[33] or possibly other hirundine species which breed in Israel.[6] However, "Yea, the sparrow hath found her a house, And the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young" from Psalms 84:3 is likely to apply to the Barn Swallow.[33]

The swallow is also notably cited in several of William Shakespeare's plays for the swiftness of its flight; for example: "True hope is swift, and flies with swallow’s wings..." from Act 5 of Richard III, and "I have horse will follow where the game Makes way, and run like swallows o'er the plain." from the second act of Titus Andronicus. Shakespeare also references the annual migration of the species poetically in The Winter's Tale, act four: "Daffodils, That come before the swallow dares, and take The winds of March with beauty; violets dim,...".

In culture

As a result of a campaign by ornithologists, the Barn Swallow has been the national bird of Estonia since 23 June 1960.[34][35]

Although Gilbert White was uncertain whether the Barn Swallow migrated or hibernated in winter, its long travels have been well-observed. A swallow tattoo is popular amongst nautical men, and the tradition was that a sailor had a tattoo of this fellow wanderer after journeying 5000 nautical miles (9260 km, 5755 statute miles) at sea. A sighting of a swallow was a sign that land was near.[36]

In the past, the tolerance for this beneficial insectivore was reinforced by superstitions regarding damage to the Barn Swallow’s nest. Such an act might lead to cows giving bloody milk, or no milk at all, or to hens ceasing to lay.[37] This may be a factor in the longevity of Swallows’ nests. Survival, with suitable annual refurbishment, for 10-15 years is regular, and one nest was said to have been occupied for 48 years.[37]

References

- ^ a b "BirdLife International Species factsheet: Hirundo rustica". BirdLife International. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Turner, Angela K (1989). Swallows & martins: an identification guide and handbook. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-51174-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p164-169 - ^ uk.rec.birdwatching, scientific bird names explained. Retrieved 28 November 2007

- ^ a b "World Cup airport 'threatens swallow population'" The Guardian 16 November 2006 (on-line) Retrieved 27 November 2007

- ^ a b c d e f Snow, David (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019854099X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p1061-1064 - ^ a b c d Mullarney, Killian (1999). Collins Bird Guide. Collins. ISBN 0-00-219728-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p242 - ^ a b Hilty, Steven L (2003). Birds of Venezuela. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-6418-5. p691

- ^ a b Barlow, Clive (1997). A Field Guide to birds of The Gambia and Senegal. Pica Press. ISBN 1-873403-32-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p279 - ^ Template:La icon Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 824.

- ^ a b c d e f Dickinson, Edward C; Eck, Siegfried; Milensky Christopher M. (2002) "Systematic notes on Asian birds. 31. Eastern races of the barn swallow Hirundo rustica Linnaeus, 1758" Zool. Verh. Leiden 340, 27.xii.2002: 201-203 Pdf retrieved 24 November 2007

- ^ a b Dickinson, Edward; Dekker, René. (2001) "Systematic notes on Asian birds. 13. A preliminary review of the Hirundinidae". Zool. Verh. Leiden 335 , 10.xii.2001: 127-144.— ISSN 0024-1652. Pdf retrieved 17 November 2007

- ^ Dekker, René.(2003) "Type specimens of birds. Part 2." NNM Tech. Bull. 6 (2003) p20 Pdf retrieved 24 November 2007

- ^ Sibley, David (2000). The North American Bird Guide. Pica Press. ISBN 1-873403-78-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Stiles, Gary (2003). A guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-7136-6418-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p343 - ^ a b Williams, Nigel (2006). "Swallows track human moves" Current Biology Volume 16, Issue 7, 4 April 2006, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.031 Text retrieved 16 November 2007

- ^ Sinclair, Ian (2002). SASOL Birds of Southern Africa. Struik. ISBN 1-86872-721-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p294 - ^ Lekagul, Boonsong (1991). A Guide to the Birds of Thailand. Saha Karn Baet. ISBN 9748567362.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p234 - ^ a b Park, Kirsty; Rosén, Mikael; Hedenström, Anders (2001) "Kinematics of the barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) over a wide range of speeds in a wind tunnel" The Journal of Experimental Biology 204, 2741–2750 (2001) Pdf retrieved 19 November 2007

- ^ a b c d e Dewey, Tanya; Roth, Chava. (2002). Hirundo rustica (On-line), University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Animal Diversity Web. Accessed November 19, 2007

- ^ Pilastro, Andrea "Euring Projects: The Euring swallow project in Italy" Euring Newsletter Volume 2, December 1998, Abstract retrieved 17 November 2007

- ^ Saino, Nicola; Romano, Maria; Sacchi; Roberto; Ninni, Paola; Galeotti, Paolo; Møller, Anders Pape (2003). "Do male barn swallows (Hirundo rustica) experience a trade-off between the expression of multiple sexual signals?" Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology Volume 54, Number 5 September, 2003. doi 10.1007/s00265-003-0642-z Abstract retrieved 16 November 2007

- ^ a b c Møller, Anders Pape; Gregersen, Jens (illustrator) (1994) Sexual Selection and the Barn Swallow. Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 0198540280 Full text on Google Book Search, retrieved 16 November 2007

- ^ Kose, Mati; Mänd, Raivo: Møller, Anders Pape (1999) "Sexual selection for white tail spots in the barn swallow in relation to habitat choice by feather lice" Animal Behaviour Volume 58, Issue 6, December 1999, Pages 1201-1205 Abstract retrieved 18 November 2007

- ^ Møller, A. P.; Tegelstrom, H. (1997). Extra-pair paternity and tail ornamentation in the barn swallow Hirundo rustica. Behav. ecol. sociobiol. 41(5):353-360.

- ^ Møller, A. P. (1985). Mixed reproductive strategy and mate guarding in a semi-colonial passerine, the swallow Hirundo rustica. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 17(4):401-408 Abstract

- ^ Møller, A. P. (1990). Deceptive use of alarm calls by male swallows, Hirundo rustica: a new paternity guard. Behav. Ecol. 1(1):1-6.

- ^ "‘World Cup 2010’ development threatens millions of roosting Barn Swallows." BirdLife International Retrieved 27 November 2007

- ^ "World Cup airport will look out for Swallows." BirdLife International Retrieved 27 November 2007

- ^ Turner, Angela K (2006). The Barn Swallow. A D Poyser. ISBN 0713665580.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:La icon Virgil, The Georgics Book IV line 307 Text retrieved 28 November 2007

- ^ Welldon, James Edward Cowell (translator). The Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, Book 1, chapter 6. Macmillan. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Nims, John Frederick (1981). The Harper Anthology of Poetry. Harper and Row. ISBN 0060448466.

- ^ a b Orr, James, (General Editor) (1915). "Definition for Swallow". International Standard Bible Encyclopedia 1915. On-line text retrieved 18 November 2007

- ^ The Estonian Embassy in London (on-line) Retrieved 19 November 2007

- ^ The Estonia Institute (on-line) symbols page Retrieved 17 November 2007

- ^ Vanishing tattoos (on-line) Retrieved 17 November 2007

- ^ a b Cocker, Mark (2005). Birds Britannica. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701169079.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Barn Swallow videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Barn Swallow - Hirundo rustica - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Barn Swallow species account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology (includes range map for the Americas)

- Barn Swallow information and photos - South Dakota Birds

- Status map for Europe (pdf)