Père Goriot

Le Père Goriot (English: Father Goriot or Old Goriot) is an 1835 novel by French novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) and included in the Scènes de la vie privée section of his novel sequence La Comédie humaine. Set in Paris in 1819, it follows three intertwined characters: the elderly title character and his self-sacrificing love for his daughters; a mysterious criminal-in-hiding named Vautrin; and a naive law student named Eugène de Rastignac.

Originally published in serial form during the winter of 1834–35, Le Père Goriot is widely considered Balzac's most important novel.[1] It marks the first serious use by the author of characters who had appeared in other books, a technique which distinguished Balzac's fiction and helped make La Comédie humaine a singular collection of writing. The novel is also cited as a noteworthy example of his realist idiom: using minute details to expose character and subtext.

Le Père Goriot depends heavily on its historical background; the 1814 Bourbon Restoration had brought profound changes in society, and the struggle of class is ubiquitous throughout the novel. The city of Paris also impresses itself on the characters – especially young Rastignac, who grew up in the provinces of southern France. Balzac analyzes, through Goriot and others, the meanings of family and marriage, providing a bleak perspective on these institutions.

Released to mixed reviews, the novel was a favorite of Balzac's, and quickly found widespread popularity among readers. He was praised by some critics for his attention to detail and his complex characters; others condemned him for his many depictions of corruption and greed. The book has been adapted for the stage and film numerous times, and has given rise to the French-language expression "Rastignac" as a social climber willing to use any means to better his situation.

Background

Historical background

Le Père Goriot begins in 1819, following Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, after the House of Bourbon had been restored to the throne of France. A tension was mounting between the aristocracy – which had returned with King Louis XVIII – and the bourgeoisie made possible by the Industrial Revolution.[2] During this tumultuous era, France saw a tightening of social structures, with a lower class steeped in overwhelming poverty. By one estimate, almost three-quarters of Parisians did not make the 500-600 francs required for a minimal standard of living.[3] At the same time, this social upheaval made possible certain forms of social mobility unthinkable during the Ancien Régime of previous centuries. Socialites willing to adapt themselves to the rules of the new society could sometimes wrestle their way into it from modest backgrounds, much to the distaste of older, established wealth.[4]

Literary background

When Balzac began writing Le Père Goriot in 1834, he had published several dozen books, including a stream of pseudonymously-published potboiler novels, as well as Louis Lambert, Le Colonel Chabert, and La Peau de chagrin.[5] He had begun organizing his work into a novel sequence called La Comédie humaine, divided into sections representing various aspects of life in France during the early 19th century.[6]

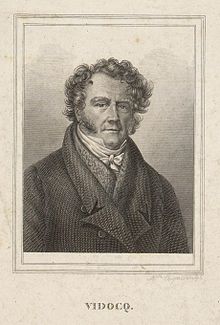

In the winter of 1828–29, a French grifter-turned-policeman named Eugène François Vidocq published a pair of memoirs – sensationalized during the revision process by his editors – recounting his criminal exploits. Balzac met Vidocq in April 1834, and decided to use him as a model for a character named Vautrin he was planning for an upcoming novel.[7]

Writing and publication

In the summer of 1834 Balzac began to work on a tragic short story about a father who is rejected by his daughters. He wrote Le Père Goriot in the fall; it was published as a serial in the Revue de Paris between December and February – growing into a full novel along the way – and appeared as a book in 1835.[8] As the structure of La Comédie humaine evolved, Le Père Goriot was added to the section "Scènes de la vie privée" ("Scenes of private life").

The character Eugène de Rastignac had appeared in Balzac's earlier philosophical fantasy novel La Peau de chagrin, as an old man. While writing the first draft of Le Père Goriot, Balzac named the character "Massiac", then suddenly decided to use the same character from La Peau de chagrin. It was his first structured use of recurring characters, a practice whose depth and rigor uniquely characterized his novels.[9]

Plot summary

The novel opens with an extended description of the Maison Vauquer, a boardinghouse on Paris' Rue Neuve-Sainte-Geneviève by the widow Madame Vauquer. The residents include the law student Eugène de Rastignac, a mysterious agitator named Vautrin, and an elderly retired vermicelli-maker named Jean-Joachim Goriot. The old man is ridiculed frequently by the other boarders, who soon learn that he has bankrupted himself to support his two well-married daughters.

Rastignac, who moved to Paris from the south of France, becomes attracted to the upper class. He has difficulty fitting in, but is tutored by his cousin in the ways of high society. He endears himself to one of Goriot's daughters, Delphine de Nucingen, after extracting money from his already-poor family. Vautrin, meanwhile, tries to convince Rastignac to pursue an unmarried woman named Victorine, whose family fortune is blocked only by her brother. He offers to clear the way for Rastignac by killing the brother in a duel.

Rastignac refuses to go along with the plot, but takes heed of Vautrin's lessons in the realpolitik of high society. Before long the boarders learn that police are seeking Vautrin, revealed to be a master criminal nicknamed Trompe-la-Mort ("Cheater of Death"). Goriot, supportive of Rastignac's interest in his daughter and furious with her husband's tyrannical control over her, finds himself unable to help. When his other daughter Anastasie informs him that she's been selling off family jewelry to pay her lover's debts, the old man is overcome with grief at his own impotence and suffers a stroke.

Vautrin has killed Victorine's brother in the meantime, and is quickly captured by the police. Neither Delphine nor Anastasie will visit Goriot as he lies on his deathbed, and before dying he rages about their disrespect toward him. His funeral is attended only by Rastignac, a servant named Christophe, and two paid mourners. After the short ceremony, Rastignac turns to face Paris as the lights of evening begin to appear. He sets out to dine with Madame de Nucingen and declares to the city: "À nous deux, maintenant!" ("It's between you and me now!")

Style

Balzac's style in Le Père Goriot is influenced by the American novelist James Fenimore Cooper and Scottish writer Sir Walter Scott. In Cooper's representations of Native Americans, Balzac saw a barbarism essential to humans that survived through attempts at civilization. In a preface to the second edition in 1835, Balzac wrote that the title character Goriot – who made his fortune selling vermicelli during a time of widespread hunger – was an "Illinois of the flour trade" and a "Huron of the grain market".[10] Scott was also a profound influence on Balzac, particularly by using real historical events as the backdrop for his novels. Although history is not central to Le Père Goriot, the post-Napoleonic era serves as an important setting, and the use of meticulous detail reflects the influence of Scott. Still, Balzac accused the Scottish writer of romanticizing the past, and tried to distinguish his own work with a more balanced view of human nature.[10][11]

The plot of Le Père Goriot is often compared to that of Shakespeare's King Lear;[12] Balzac was even accused of plagiarism when the novel was first published.[13] Demonstrating the similarities, critic George Saintsbury claims that Goriot's daughters are "as surely murderesses of their father as [Lear's daughters] Goneril and Regan".[14]

Although the novel is often referred to as "a mystery",[15] it is not an example of whodunit or detective fiction. Instead, the puzzles to be solved are the origins of suffering and the causes of unusual behavior. Characters appear in fragments, with brief scenes providing small clues about their identity. Vautrin, for example, slips in and out of the story – offering advice to Rastignac, ridiculing Goriot, bribing the housekeeper Christophe to let him in after hours – before he is revealed as a master criminal. This pattern mirrors Balzac's general use of characters throughout La Comédie humaine.[16]

Recurring characters

Le Père Goriot marks an important early instance of Balzac's trademark technique of recurring characters, whereby persons from earlier novels appear in later works, usually during significantly different times of life.[17] Pleased with the effect he achieved with the return of Rastignac, Balzac included 23 recurring characters in the first edition of Le Père Goriot; during his revisions for later editions the number increased to 48.[18] Although Balzac had used this tactic before, the characters had always reappeared in minor roles, as nearly-identical versions of the same people. Rastignac's appearance shows, for the first time in Balzac's fiction, a novel-length back-story which fully illuminates and develops a returning character.[19]

Balzac experimented with this method actively during the thirty years he worked on La Comédie humaine. It allowed a depth of characterization that went beyond simple narration or dialogue. "When the characters reappear", notes the critic Rogers, "they do not step out of nowhere; they emerge from the privacy of their own lives which, for an interval, we have not been allowed to see."[20] Although the complexity of these characters' lives inevitably led Balzac to commit errors of chronology and consistency, they are considered minor in the overall scope of the project.[21] Readers are more often troubled by the sheer number of people in Balzac's world, and feel deprived of important context for the characters. Detective novelist Arthur Conan Doyle once claimed that he never tried to read Balzac, because he "did not know where to begin".[22]

Realism

Balzac uses intense detail to describes the Maison Vauquer, its inhabitants, and the opulent luxury of the upper classes; this technique gave rise to his title as the father of the realist novel.[23] These details focus mostly on the penury of the residents of the Maison Vauquer. Much less intricate are the descriptions of wealthier homes; Madame de Beauséant's rooms are given scant attention, and the Nucigen family lives in a house sketched in the briefest detail.[24]

At the start of the novel, Balzac declares (in English): "All is true". Although the characters and situations are fiction, the details employed – and their reflection of the realities of life in Paris at the time – create a faithful rendering of the world of the Maison Vauquer.[25] The Rue Neuve-Sainte-Geneviève (where the house is located) presents "a grim look about the houses, a suggestion of a jail about those high garden walls".[26] The interiors of the house are painstakingly described, from the shabby sitting room ("Nothing can be more depressing") to the coverings on the walls ("papers that a little suburban tavern would have disdained"), which depict a feast in a house known for its wretched food.[27] Balzac borrowed the latter detail from the expertise of his friend Hyacinthe de Latouche, who was trained in the practice of hanging wallpaper.[28] The house is even defined by its repulsive smell, undefinable except as unique to the poor boardinghouse.[29]

Themes

Social stratification

The boundaries of society's strata and the urgency of ascending them are ubiquitous throughout Le Père Goriot. The Charter of 1814 granted by King Louis XVIII of France had established a "legal country" which allowed only a small group of the nation's most wealthy men to vote. Thus, Rastignac's drive to achieve social status is evidence not only of his personal ambition, but also of his desire to participate in the body politic. As with Scott's characters, the historical milieu in which he lives is reflected in Rastignac's attitude.[30]

Balzac and his characters employ no nuance in describing the social Darwinism of this society. In one particularly blunt speech, Mme. de Beauseant tells Rastignac explicitly:

The more cold-blooded your calculations, the further you will go. Strike ruthlessly; you will be feared. Men and women for you must be nothing more than post-horses; take a fresh relay, and leave the last to drop by the roadside; in this way you will reach the goal of your ambition. You will be nothing here, you see, unless a woman interests herself in you; and she must be young and wealthy, and a woman of the world. Yet, if you have a heart, lock it carefully away like a treasure; do not let any one suspect it, or you will be lost; you would cease to be the executioner, you would take the victim's place. And if ever you should love, never let your secret escape you![31]

This attitude is further explored by Vautrin, who tells Rastignac: "The secret of a great success for which you are at a loss to account is a crime that has never been found out, because it was properly executed."[32] This sentence has been frequently paraphrased as: "Behind every great fortune is a great crime."[33]

Influence of Paris

The novel's representations of social stratification are specific to Paris, which was perhaps the most densely populated city in Europe at the time.[34] Traveling only a few blocks – as Rastignac does continually – takes the reader into vastly different worlds, distinguished mostly by the class of their inhabitants. Paris in the post-Napoleonic era was split into distinct neighborhoods. Three of these are featured prominently in Le Père Goriot: the aristocratic area around the Boulevard Saint-Germain, the newly upscale region of the Rue de la Chaussée d'Antin, and the run-down area on the eastern slope of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève.[35]

These regions of the city serve as microcosms through which Rastignac seeks to ascend; Vautrin, meanwhile, attempts to operate in stealth, moving among them without his criminal nature being detected.[36] Rastignac, as the naive young man from the country, seeks in these worlds a new home. Paris offers him a chance to abandon his far-away family and remake himself in the city's ruthless image.[37] His urban exodus is like that of the many people who moved into the French capital, doubling its population between 1800 and 1830. The texture of the novel is thus inextricably linked to the city in which it is set; "Paris", explains critic Peter Brooks, "is the looming presence that gives the novel its particular tone".[38]

Corruption

Both Rastignac and Goriot himself represent individuals corrupted by their desires. In his thirst for advancement, Rastignac has been compared to Faust with Vautrin as Mephistopheles.[39] Critic Pierre Barbéris calls Vautrin's lecture to Rastignac "one of the great moments of the Comédie humaine, and no doubt of all world literature".[40] The shifting sands of the events in France provided Vautrin with a playground for an ideology devoid of any value aside from personal advancement; he guides Rastignac in the same direction.[41]

Still, it is the larger social structure which overwhelms Rastignac's soul—Vautrin merely explains the methods and causes. Although he rejects Vautrin's offer of murder, Rastignac succumbs to the principles of brutality upon which high society is built. By the end of the novel he tells Bianchon: "I'm in Hell, and I have no choice but to stay there."[42]

While Rastignac desires wealth and social status, Goriot longs only for the love of his daughters: a longing which borders on idolatry.[43] Because he represents bourgeois wealth acquired through trade – and not aristocratic primitive accumulation – his daughters are happy to take his money, but will only see him in private. Even as he is dying at the end of the book, he sells his few remaining possessions to provide for his daughters.[44]

Family relations

The relations between family members follow two patterns: the bonds of marriage serve mostly as Machiavellian means to financial ends, while the obligations of the older generation to the young take the form of sacrifice and deprivation. Delphine and Anastasie use their father's fortune to marry into established families, and their husbands likewise use money as an instrument of power. This depiction of marriage as a weapon of prestige reflects the harsh reality of the unstable social structures of the time.[45]

Parents, meanwhile, give endlessly to their children; Goriot literally sacrifices everything for his daughters. Balzac refers to him in the novel as the "Christ of paternity" for his constant suffering on behalf of his children.[46] That they abandon him only adds to his misery. The end of the book contrasts Goriot's final moments on his death bed with a festive ball hosted by Madame de Beauséant – attended by his daughters, as well as Rastignac – suggesting an irreconcilable split between society and the family.[47]

Rastignac's family also sacrifices extensively for him. Convinced that he cannot achieve a decent status in Paris without a considerable display of wealth, he writes to his family and asks them to send him money: "Sell some of your old jewelry, my kind mother; I will give you other jewels very soon."[48] They do send him the money he requests, and – although it is not described directly in the novel – endure significant hardship for themselves as a result. His family, absent while he is in Paris, becomes even more distant despite this sacrifice. Although Goriot and Vautrin offer themselves as father figures to him, by the end of the novel they are gone and he is alone.[49]

Reception and legacy

Le Père Goriot is widely considered Balzac's finest novel.[1] Critic Peter Brooks refers to its "perfection of form, its economy of means and ends".[50] Martin Kanes, meanwhile, in his book Le Pére Goriot: Anatomy of a Troubled World, calls it "the keystone of the Comédie humaine".[51] It serves as the central focus of Anthony Pugh's voluminous study Balzac's Recurring Characters, and entire chapters have been written about the detail of the Maison Vauquer.[52] Because it has become such an important novel for the study of French literature, Le Père Goriot has been translated many times with careful attention paid to nuances of language. Thus, says Balzac biographer Graham Robb, "Goriot is one of the novels of La Comédie humaine that can safely be read in English for what it is."[53]

Initial reviews of the book were mixed. In addition to charges of plagiarism, reviewers accused Balzac of overwhelming the reader with detail and painting a simplistic picture of Parisian high society.[54] Others attacked the questionable morals of the characters, implying that Balzac was guilty of legitimizing their opinions. He was condemned for not including more individuals of honorable intent in the book.[55] Balzac responded with disdain to these charges; in the second preface of 1835, he wrote with regard to Goriot: "Poor man! His daughters refused to recognize him because he had lost his fortune; now the critics have rejected him with the excuse that he was immoral."[56]

Many critics of the time, though, were more positive: a review in Le Journal des femmes proclaimed that Balzac's eye "penetrates everywhere, like a cunning serpent, to probe women's most intimate secrets".[57] Another review in La Revue du théâtre praised his "admirable technique of details".[57] The sheer number of reviews was itself evidence of the book's popularity and success. One publisher's review dismissive of Balzac as a "boudoir writer" nevertheless predicted for him "a brief career, but a glorious and enviable one".[57]

Balzac himself was extremely proud of the work, declaring even before the final installment was published: "Le Père Goriot is a raging success; my fiercest enemies have had to bend the knee. I have triumphed over everything, over friends as well as the envious."[58] As was his custom, he revised the novel between editions; compared to other novels, however, Le Père Goriot remained largely unmolested after its initial text was released.[54]

In the years following its release, the novel was adapted numerous times for the stage. Two theatrical productions in 1835 – several months after the book's publication – sustained its popularity and increased the public's regard for Balzac.[59] In the twentieth century, a variety of film versions have been produced, including adaptations directed by Jacques de Baroncelli, Travers Vale, and Paddy Russell. The name of Rastignac, meanwhile, has become an iconic title in the French language; a "Rastignac" is synonymous with a person willing to climb the social ladder at any cost.[50]

Notes

- ^ a b Hunt, p. 95; Brooks (1998), p. ix; Kanes, p. 9.

- ^ Kanes, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Kanes, p. 38.

- ^ Brooks (1998), p. xi.

- ^ Robb, pp. 425–429.

- ^ Saintsbury, p. ix.

- ^ Hunt, p. 91.

- ^ Brooks (1998), p. viii; Kanes, p. 7.

- ^ See generally Pugh.

- ^ a b Kanes, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Kanes, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Hunt, pp. 87–89; Robb, p. 257.

- ^ Kanes, p. 13.

- ^ Saintsbury, p. x.

- ^ Barbéris, p. 306; Kanes, pp 26–27.

- ^ Kanes, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Pugh, p. 57; Hunt, 93–94. Pugh makes it clear that other authors – namely Robert Chasles, Pierre Beaumarchais, and Restif de la Bretonne – had used this technique earlier, although Balzac did not mindfully follow in their footsteps.

- ^ Robb, p. 253; Hunt, p. 94; Pugh, pp. 73–81.

- ^ Pugh, pp. 78–79; Brooks (1998), pp. vii–ix.

- ^ Rogers, 182.

- ^ Robb, p. 254.

- ^ Quoted in Robb, p. 254; see generally Pugh.

- ^ Brooks (2005), p. 16; Auerbach, p. 280.

- ^ Mozet, pp. 348–349; Kanes, p. 37.

- ^ Auerbach, p. 282.

- ^ Balzac (1901), p. 3.

- ^ Balzac (1901), pp. 5 and 18, respectively; Mozet, p. 351.

- ^ Robb, 152.

- ^ Kanes, p. 52.

- ^ Kanes, p. 38.

- ^ Balzac (1901), p. 79.

- ^ Balzac (1901), p. 115.

- ^ See for example Porter, Eduardo. "Mexico’s Plutocracy Thrives on Robber-Baron Concessions". New York Times, 27 August 2007. Online at nytimes.com. Retrieved on 13 January 2008.

- ^ Kanes, p. 41.

- ^ Kanes, p. 36.

- ^ Kanes, p. 44.

- ^ Barbéris, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Brooks (1998), p. x.

- ^ Kanes, p. 45.

- ^ Barbéris, p. 307.

- ^ Barbéris, p. 309.

- ^ Quoted in Barbéris, p. 312.

- ^ Hunt, p. 89; Crawford, p. 13.

- ^ Petrey, p. 329.

- ^ Kanes, pp. 46–49; Auerbach, p. 285.

- ^ Kanes, p. 47.

- ^ Petrey, p. 337.

- ^ Balzac (1901), p. 85.

- ^ Barbéris, pp. 310–314.

- ^ a b Brooks (1998), p. ix.

- ^ Kanes, p. 9.

- ^ See Mozet, as well as Downing, George E. "A Famous Boarding-House". Studies in Balzac's Realism. E. P. Dargan, ed. New York: Russell & Russell, 1932.

- ^ Robb, p. 258.

- ^ a b Kanes, p. 13.

- ^ Kanes, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Quoted in Kanes, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Quoted in Kanes, p. 15.

- ^ Quoted in Kanes, p. 12.

- ^ Kanes, pp. 15–16.

Bibliography

- Auerbach, Erich. "[Père Goriot]". Père Goriot. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97166-X. pp. 279–289.

- Balzac, Honoré de. Father Goriot. The Works of Honoré de Balzac. Vol. XIII. Philadelphia: Avil Publishing Company, 1901.

- Balzac, Honoré de. Père Goriot. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97166-X.

- Barbéris, Pierre. "The Discovery of Solitude". Père Goriot. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97166-X. pp. 304–314.

- Brooks, Peter. "Editor's Introduction". Père Goriot. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97166-X. pp. vii–xiii.

- Brooks, Peter. Realist Vision. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0300106807.

- Crawford, Marion Ayton. "Translator's Introduction". Old Goriot. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1951. ISBN 0-14-044-017-8.

- Hunt, Herbert J. Balzac's Comédie Humaine. London: University of London Athlone Press, 1959. OCLC 4566561.

- Kanes, Martin. Père Goriot: Anatomy of a Troubled World. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0-8057-8363-6.

- Mozet, Nicole. "Description and Deciphering: The Maison Vauquer". Père Goriot. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97166-X. pp. 338–353.

- Petrey, Sandy. "The Father Loses a Name: Constative Identity in Le Père Goriot". Père Goriot. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97166-X. pp. 328–338.

- Pugh, Anthony R. Balzac's Returning Characters. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974. ISBN 0-8020-5275-4.

- Robb, Graham. Balzac: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994. ISBN 0-393-03679-0.

- Rogers, Samuel (1953). Balzac & The Novel. New York: Octagon Books. LCCN 75-0.

- Saintsbury, George. "Introduction". The Works of Honoré de Balzac. Vol. XIII. Philadelphia: Avil Publishing Company, 1901.