Arch

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

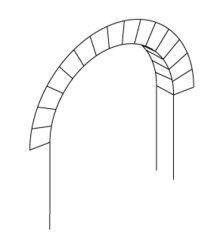

1. Keystone 2. Voussoir 3. Extrados 4. Impost 5. Intrados 6. Rise 7. Clear span 8. Abutment

An arch is a curved structure capable of spanning a space while supporting significant weight (e.g. a doorway in a stone wall). The arch appeared in Mesopotamia, Indus Valley civilization, Egypt, Assyria and Etruria, and later refined in Ancient Rome. The arch became an important technique in cathedral building and is still used today in some modern structures such as bridges.

History

Arches were used by the Persian, Harappan, Egyptian, Babylonian, Greek and Assyrian civilizations for underground structures such as drains and vaults, but the ancient Romans were the first to use them widely above ground although it is thought that Romans learned it from the Etruscans. The arch has been used in some bridges in China since the Sui dynasty and in tombs since the Han Dynasty.[citation needed]

The so-called Roman arch is semicircular, and built from an odd number of arch bricks (called voussoirs). You need an odd number of bricks for there to be a capstone or keystone. This the topmost stone in the arch. An Arch's shape is the simplest to build, but not the strongest. There is a tendency for the sides to bulge outwards, which must be counteracted by an added weight of masonry to push them inwards. The semicircular arch can be flattened to make an elliptical arch. The Romans used this type of semicircular arch freely in many of their secular structures such as aqueducts, palaces and amphitheaters.[citation needed]

The semicircular arch was followed in Europe by the pointed Gothic arch or ogive, whose centreline more closely followed the forces of compression and which was therefore stronger. This design had been used by the Assyrians as early as 722 BC. The parabolic and catenary arches are now known to be the theoretically strongest forms. A parabolic arch was introduced in the Ponte Santa Trinita, Florence, constructed by the architect Bartolomeo Ammanati from 1567 to 1569. Parabolic arches were introduced in construction by the Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí, who admired the structural system of Gothic style, but for the buttresses, that were designated by him “architectural crutches”. The catenary and parabolic arches carry all horizontal thrust to the foundation and so do not need additional elements.

The horseshoe arch is based on the semicircular arch, but its lower ends are extended further round the circle until they start to converge. The first examples known are carved into rock in India in the first century AD, while the first known built horseshoe arches are known from Aksum (modern day Ethiopia and Eritrea) from around the 3rd–4th century, around the same time as the earliest contemporary examples in Syria, suggesting either an Aksumite or Syrian origin for the type of arch.[1] It was used in Spanish Visigothic architecture, Islamic architecture and mudéjar architecture, as in the Great Mosque of Damascus and in later Moorish buildings. It was used for decoration rather than for strength.

Construction

An arch requires all of its elements to hold it together, raising the question of how an arch is constructed. One answer is to build a frame (historically, of wood) which exactly follows the form of the underside of the arch. This is known as a centre or centring. The voussoirs are laid on it until the arch is complete and self-supporting. For an arch higher than head height, scaffolding would in any case be required by the builders, so the scaffolding can be combined with the arch support. Occasionally arches would fall down when the frame was removed if construction or planning had been incorrect. (The A85 bridge at Dalmally, Scotland suffered this fate on its first attempt, in the 1940s). The interior and lower line or curve of an arch is known as the intrados.

Old arches sometimes need reinforcement due to decay of the keystones, known as bald arch.

The gallery shows arch forms displayed in roughly the order in which they were developed.

-

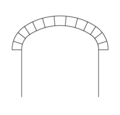

Round arch or Semi-circular arch

-

Unequal round arch or Rampant round arch

-

Three-foiled cusped arch

Other types

A blind arch is an arch infilled with solid construction so it cannot function as a window, door, or passageway.

A dome is a three-dimensional application of the arch, rotated about the center axis. Igloos are notable early structures making use of domes.

Natural rock formations may also be referred to as arches. These natural arches are formed by erosion rather than being carved or constructed by man. See Arches National Park for examples.

A special form of the arch is the triumphal arch, usually built to celebrate a victory in war. A famous example is the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, France.

A vault is an application of the arch extended horizontally in two dimensions; the groin vault is the intersection of two vaults.

Gallery

-

Doubled round archivolts - Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Assunção, Linhares da Beira, Portugal.

-

Stonework arches seen in a ruined stonework building - Burg Lippspringe, Germany

-

Several arches at the Casa Simón Bolívar in Havana, Cuba

References

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press. 1991. ISBN 0-7486-0106-6, p.111.

- Roth, Leland M (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements History and Meaning. Oxford, UK: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-430158-3. pp. 27-8

See also

External links

- DIYinfo.org's Constructing Brick Arches Wiki - A wiki on how to construct brick arches around the house

- DIYinfo.org's Constructing Timber Framed Arches Wiki - Similar to the brick arches but extra information for timber arches