Facundo

| File:Facundo sarmiento.jpg The cover of a recent translation, from the University of California Press. | |

| Author | Domingo Faustino Sarmiento |

|---|---|

| Translator | Kathleen Ross |

| Language | Spanish |

| Publisher | El Progreso de Chile (first, serial, edition in original Spanish) University of California Press (Kathleen Ross translation) |

Publication date | 1845 |

| Publication place | Argentina |

Published in English | 1868 (Mary Mann translation) 2003 (Kathleen Ross translation) |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 284 |

| ISBN | ISBN 0-520-08159-5, paper ISBN 0-520-23980-6 (Kathleen Ross translation) Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

Facundo (subtitled Civilization and Barbarism) is a book written by the Argentine author and politician Domingo Faustino Sarmiento in 1845. It was written partly in protest against the regime of Juan Manuel de Rosas, who ruled Argentina from 1829 to 1832 and from 1835 to 1852. The literary critic Roberto González Echevarría calls it "the most important book written by a Latin American in any discipline or genre."[1]

This book describes the life of Juan Facundo Quiroga. By describing this gaucho, the author gives us the best exemplification of the Argentine culture, the best description of the Argentine context and, at the same time, Sarmiento found himself in a dichotomy between civilization and barbarism.

Sarmiento published this book to "denounce the tyranny of the Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas"[2] Sarmiento attacks Rosas in various ways through his description on the Argentine national character, explanation of the effects of the geographical conditions of Argentina on personality, the contrast of barbarism and civilization in Argentina, and expression of optimism to the future of Argentina when European civilization ideas would influence the Argentines.[2]

This book is an essay united by Sarmiento's underlying theme of a single dichotomy: civilization and barbarism. Civilization is represented by European countries such as France and Britain, cities in Argentina, Unitarians, General Paz, and Rivadavia. On the contrary, barbarism is identified with Latin American countries, rural areas in Argentina, Federalists, as well as Juan Facundo Quiroga and the dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas.[3] The main character of this book Juan Facundo Quiroga, who was both a caudillo and leader of the provincial area of Argentina, represents barbarism in the countryside.[4]

Background

Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism was written by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento while he was living in exile in Chile in 1845. Nowadays, it is recognized as "one of the foundational works of Spanish American literary history". It attempts to set up a new cultural identity for the post-Independence Latin nations and it marks a turning point in the evolution of literature. Buenos Aires is the name of the Argentina’s largest and most prosperous city. It has a coastal and a river access. Therefore, it has proved to be a prime city to trade; the city receives goods, capital and new ideas from all over the world. In the nineteenth century, Buenos Aires became a city characterized by European culture. By comparison, other Argentine cities of this era were small and insulated. Therefore, it was a certain antagonism arose between Buenos Aires and the rest of Argentina."[5]

Argentine civil war

In 1826 an assembly elected Bernardino Rivadavia as president of the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata. This action roused the ire of the provinces, and civil war was the result. Support for a strong, centralized Argentine government was based in Buenos Aires, and gave rise to two opposing groups. On the one hand, there were the Unitarians, those favoring centralized government (tended to be wealthy and educated). The rest o the country tended to favor a looser federation with more autonomy for the individual provinces known as Federalists (tended to be rural inhabitants and rejected to imitate European ways). "[6]

The perception about the Rivadavia government, was divided in the two different ideologies. For the Unitarians as Sarmiento it was a good experience the Rivadavias presidency: He established a good university, supported a public education program for male rural children. He also supported theater and opera groups, publishing houses and a museum. Less happy were the Federalists as Juan Facundo Quiroga or Juan Manuel de las Rosas, because Rivadavia arrested the gauchos for vagrancy and forced to work on public projects, usually without pay."[5]

Beset by Federalist forced, and losing a war against Brazil, Rvadavia left the presidency in 1827. Manuel Dorrego became governor of the Buenos Aires province with the help of the fellow Federalist Juan Manuel de las Rosas. Dorrego made peace with Brazil by sacrificing a large piece of disputed territory. Argentine troops, having returned from the war zone, proceeded to overthrow and execute Dorrego, installing their leader the Unitarian general Juan Lavalle, as governor."[7]

Lavalle was soon overthrown himself, by Rosas-led militia composed largely of gauchos. By the end of 1829 the old legislature that Lavalle had disbanded was back in place and had appointed Rosas as governor of Buenos Aires."[7]

Rosas dictatorship

The Rosas dictatorship was characterized by the big differences between the high and poor class, it was not a middle class in the Argentinean society. Rosas created a big gap between both groups. During this time, with the help of Facundo Quiroga, Rosas maintained peace between Buenos Aires and the rest of Argentina. Rosas enjoyed general support until stepped down form office at the end of this three year term."[7]

Without the strength of Rosas, the nation soon dissolver into chaos. The provinces were demanding a constitution that would give them a more equitable relationship with Buenos Aires, whose government appeared threatened by Unitarian forces. The assassination of Juan Facundo Quiroga in 1835 promised anarchy; to avert this the Buenos Aires legislature begged Rosas to resume the governorship on his own terms. His terms were absolute power and Rosas ruled as dictator the next 17 years."[7]

Synopsis

This book is divided into 15 chapters, with an author's note and introduction by Sarmiento. It provides Sarmiento's point of view with sources to support. It is difficult to classify this book in a specific genre as "it combines history, biography, sociology, geography, poetic description, and political propaganda".[2] It is further subdivided into 3 parts in which the first part (includes Chapter I to IV) is about the Argentine geography and history. The second part (includes Chapter V to XIV) is about Juan Facundo Quiroga's life and the third part (includes Chapter XV) is Sarmiento's vision of the possible future of Argentina under a Unitarists government. [8]

Argentine context

Sarmiento begins Facundo by providing a physical description of Argentina. This Chapter begins with Sarmiento's description of the geography of Argentina. It is described as vast and expanse. It lies from the east of Chilean Andes to the west of the Atlantic Ocean and there are rivers in between which are finally joined in the Río de la Plata. Sarmiento suggests that Buenos Aires is the only city that could benefit from the river systems and could most likely achieve civilization in Argentina but Buenos Aires failed to influence the rest of Argentina. Thus, barbarism continues to exist in the rest of Argentina. As a result, the dictator Rosas was produced and he in turn took control of Buenos Aires. Sarmiento then explains the reasons why Argentina failed to attain civilization. Argentine lands are mostly pampas which are flat and vast terrains. Due to this geographical condition, there is no place for hiding nor for defensing.[9]

Sarmiento then illustrates the originality of Argentine culture and introduces four different types of gaucho: the rastreador, baqueano, the bad gaucho, and the cantor. Sarmiento explains that although the geographical condition of Argentina created barbarism, it has made the inhabitants poetic due to the dramatic natural environment. Sarmiento believes the literature of the Americas should reflect the special geographic situation in Argentina and should also illustrate "the struggle between European civilization and indigenous barbarism, between intelligence and matter." [10] Furthermore, Sarmiento explains that the descriptions of the four different types of gaucho helps to understand and clarify the characters of various Argentine leaders. Among the leaders that Sarmiento refers to, Rosas is one of them.

After that, Sarmiento explains that Argentine peasants are "independent of all need, free of all subjection, with no idea of government."[11] Hence, they turn to the gatherings in the pulpería where they spent their days drinking and gambling. They prove themselves through horsemanship and knife fighting. Although killing did not happen often, when it did, Rosas' residence was used as an asylum for these killers. According to Sarmiento, these are important facts that help to understand the revolution in which Argentina gained independence from Spain. The revolution brought military association called montoneras which propelled caudillos to power and led to the triumph of Facundo Quiroga.[12] [13]

Sarmiento continues to talk about the Argentine Revolution in 1810. The revolution of independence was inspired by the Europeans ideas. Only in cities like Buenos Aires could these civilized ideas influence Argentine people. Rural areas where it was full of barbarism, the inhabitants participated in the revolution since war allowed them to be aggressive and brutal. However, the revolution was not successful since afterwards these barbaric inhabitants despoiled the civilization in the cities.[13]

Biography of Juan Facundo Quiroga

Sarmiento gives a biography of Juan Facundo Quiroga, the "Tiger of the Plains". Facundo was born in a wealthy family but he received little education. He was a an avid gambler when he was young and he was antisocial and rebellious. Although his family was rich, he gambled away all his money which he inherited and this broke off his relations with his family. He also burned down the house where his parents lived in. He became an outlaw and he joined the caudillo in the Entre Ríos province. However, he was captured and sent to jail before he joined the band. A group of Spaniards were imprisoned with Facundo and they broke open the cells one day. When Facundo was released along with the Spaniards, he killed all of them and became a hero. After that, he arrived at the province of La Rioja and others gave him the title of sergeant major of the Llanos Militia, [14] whether from fear or esteem. He was courageous and fierce in battles and he suppressed his enemies by killing them. Although he became powerful and wealthy, he hated things he could not acquire—"fine manners, an education, a basis for respectability" [15]—and destroyed people who have them. His barbaric nature caused the once properous La Rioja to ruins.[16]

Sarmiento then illustrates the dichotomy of civilization and barbarism in two cities of Argentina: Buenos Aires and Córdoba. Sarmiento continues with the life of Facundo. Rivadavia , who was a governor of Buenos Aires , summon all leaders from the provinces in 1825. Facundo went there as a representation of La Rioja and he was ordered to repress a military leader who had too much power. He was successful and at his victory he raised his flag which was "a black cloth with a skull and crossbones in the middle" [17]. Sarmiento then contrasts Facundo's flag with Argentina's flag which the former represents "Death, fear, hell" [17] and the latter symbolizes "justice, peace, justice" [18]

Rivadavia soon resigned and was replaced by Dorrego who was a Federalist. However, he was not concerned about ending barbarisms in the provinces. Thus, Buenos Aires failed to bring civilization to the rest of Argentina and led to the dictatorship of Rosas. Dorrego was killed during the revolt of the Unitarists. Facundo was defeated by General Paz in the battle. Sarmiento contrasts Facundo with Paz and describes the latter as "the most total representative of the power of civilized peoples" [19]. Facundo escaped to Buenos Aires and joined Rosas' government. Soon after Rosas' government started to oppose the Unitarists and Facundo successfully conquered Rio Quinto, San Luis, and Mendoza. Facundo then returned to San Juan where he exercised his power over neighbouring towns but his power was not recognized by Rosas. Eventually Facundo returned to Buenos Aires to confront with Rosas and he also proclaimed himself a Unitarist though he did not support the Unitarians. Rosas resumed the dictatorship and became a despot he destroyed the governors who were interfering his rule over Argentina. Facundo was sent away to settle a dispute in north Buenos Aires by Rosas but his carriage was stopped halfway and Facundo was shot dead. According to Sarmiento, he believes the murder was plotted by Rosas: "An impartial history still awaits facts and revelations, in order to point its finger at the instigator of the assassins". [20]

History context after death of Juan Facundo Quiroga

In the final chapters, Sarmiento delves into the consequences that derived from Juan Facundo Quiroga's death in the historical events and politics of the Argentine Republic. [21] Sarmiento concludes all the tension that was in the chapter "Barranca Yaco". There are more analyses and opinions about the Rosas government in these final chapters and Sarmiento's thoughts towards the final goal of the dictator. Sarmiento describes the dictatorship, the tyranny, the use of force to maintain the order and the stability, the support of the people, and as the main point, the Rosas personality. Sarmiento criticizes Rosas by using the words of the dictator, making sarcastic comments about what Rosas was doing and describing the “terror” that was established during the dictatorship, the contradictions of the government and the situation in the provinces that were ruled by Facundo. Finally, in the last chapter, Sarmiento is describing the consequences of the Rosas government, attacking the dictator and establishing a bigger dichotomy. By describing the situation in the relations between France and Argentina, Sarmiento is making another comparison between the culture and the savagism.

Style

Ezequiel Martínez Estrada states "I never took Facundo by Sarmiento, as a historical work, nor do I think it can be very valued in that regard. I always thought of it as a literary work, as a historical novel"[22] However, Facundo can not be classified as a novel or as an specific genre of the literature. The book has characteristics of a novel with a biography and of a historical description of a particular event. Therefore, it is very difficult to define a particular genre in this book. Instead of that, it would much easier to define the particularities of the writing style of Sarmiento to understand better the book.

In Sarmiento’s style, the author's background is crucial: Sarmiento was primarily a militant soul and we can not separate his actions out of the book. Therefore, the book has an specific ideology and Sarmiento used it as a tool to fight his enemies.[23]

The book can be divided into 3 broad sections: The first is the description of the environment; the second is the description of the character (Facundo Quiroga). And finally, in the last two chapters of the book, Sarmiento makes a historical description.[24]

The three sections are joined by the Sarmiento's style. There is no a transition between the first chapters and the ones that are describing the Facundo Quiroga's life. The first chapters talk about the environment in Argentina and Facundo Quiroga is a natural consequence of this environment.[25]

Main Characters

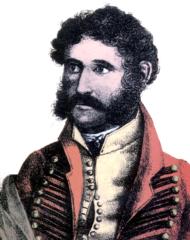

Facundo

Facundo, that is, Juan Facundo Quiroga, is the book's central character. He was also called the "Tiger of the Plains."[26] He is also described as being "el jugador", meaning the player. [27] The protagonist liked to gamble and gambling for him was like "an ardent passion burning in his belly"[28] Facundo is portrayed as wild and untamed in Argentina, just like a normal caudillo at that time. Facundo Quiroga, son of San Juan, had a narrow education, only reading and writing. This again shows that Caudillos, such as Facundo, were more barbaric than civilized, which links to one of the themes of the book. During his childhood, Facundo was portrayed as being stubborn, uninvolved and a loner.[29].

When the protagonist was called El General Don Juan Gacundo Quiroga, he was of a short yet muscular stature. His body was well built with wide, broad shoulders with a short neck supporting his slightly oval shaped face. His hair was curly and thick just like his black beard (features of a normal caudillo at that time) His strong black eyes, covered by his thick eyebrows, filled with passion and wilderness, were a key element that terrified many.[26] "Quiroga governed San Juan solely with his terrifying name."[30]

Juan Manuel de Rosas

Sarmiento wrote Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism as taking vengeance against the dictator Rosas during whose reign Facundo was written. This book wrote about Juan Facundo Quiroga as "a vantage point from which to explore the social and historical situation" under the tyranny of Rosas.[31]

Juan Manuel de Rosas was a landowner, a rural caudillo, and the dictator of Buenos Aires from 1829 to 1852.[32] He was born in a family that was wealthy and with high status in the society but his harsh and hard mother had a powerful influence on him.[33] Sarmiento believes that because of his mother, "the spectacle of authority and servitude must have left lasting impressions on him."[34] He was banished to an estancia when he was barely into puberty and he had resided there for almost thirty years ever since. He established an authoritative association dealing with matters regarding the estancias by 1824 and above all he introduced harsh administration into his estancias. Sarmiento points out that this is the type of government he tried out later on in Buenos Aires.[35]

Sarmiento also compares how Rosas ruled a country to how he governed the estancias. Rosas imprisoned many of his citizens for unknown reasons and for long years was just like the roundup in which cattles were tamed and closed up inside the corral everyday. Besides, the whippings in the street and the massacres were his methods of making his citizens like the "tamest, most orderly cattle known."[36]

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

In Facundo, Sarmiento is the narrator and a main character at the same time. The book has autobiographical elements that represent events in Sarmiento’s life. During the lecture, Sarmiento has an opinion about all the Argentine situation; therefore, there are some analysis with his own opinion and some historical chronicles about certain events. [37]

In the dichotomy between civilization and barbarism, Sarmiento represented civilization; he was impregnated by the European and American ideas. In the book, he represents the education and the development. Meanwhile, Rosas and Facundo were symbolized as being barbaric.

In the real life, Sarmiento was an educator, a civilized man who was a militant of the Unitarian movement; during the civil war, he fought against Juan Facundo Quiroga in several times. While he was in Spain, Sarmiento was a member of the Literary Society of Professors. [38] He was an exile in Chile when he started to write Facundo. As a politician, he was member of the senate after the Rosas' fall and was president of Argentina for six years (1868–1874).

During his presidency, Sarmiento concentrated on migration, the science and the culture. His ideas were based in the European civilization. For him, the development of a country was based in the education; therefore, he founded the military and the naval colleges.

Themes

Civilization and Barbarism

"That is the point: to be or not to be savages"[39]

The dichotomy that Sarmiento expresses between "barbarism" and "civilization" is the book's central idea. The book is a critique of Rosas's dictatorship but also is a broader investigation into Argentine history and culture. The book is ostensibly a biography of the caudillo Juan Facundo Quiroga, who is portrayed as wild and untamed in Argentina, and as standing in opposition to true progress through the common enlightenment of European society. The book implies that the only way to truly achieve progress and a better world is through the taming of such leaders and a common education allowing the common man to philosophically recognize and oppose such exploitation.[citation needed]

The dichotomy of civilization and barbarism illustrates the struggle in the post-Independence era. Although Sarmiento was not the one to create this dichotomy, he turns it into an influential concept in all Latin America Literature.[40] Sarmiento explores the issue of civilization versus the cruder aspects of a caudillo culture of brutality and absolute power. Caudillo is a word denoting "a political-military leader at the head of an authoritative power". Caudillos are seen, at the beginning of the book, as the opposite of education, high culture, and civil stability. Caudillos introduce instability and chaos, which destroy societies through their blatant disregard for humanity and social progress. Sarmiento portrays the rise of Facundo Quiroga, an archetypical Argentine caudillo, his controversial rule, and his downfall. Civilization is represented by the metropolitan society of Buenos Aires.

Although most only connect the book with contemporary Argentinean history, some also apply it to the wider social questions facing Latin America as a whole during the mid-19th century. As caudillos took control and set up authoritarian governments, in the book, questions of what is best for the progress of society were largely ignored by the ruling elite for the more immediate goal of exploiting the masses.

Facundo, when interpreted as a critique of both Rosas and caudillos at large, introduces an opposition message that promoted an alternative that was more beneficial to society at large. This included education and honest officials who understood enlightenment ideas of European and Classical origin. Education was an essential key to Sarmiento. He viewed barbarism, linked with ignorance, poverty, lack of education, anarchy and so on, as a never ending line of social ills. The wilderness that Facundo demonstrates was one of Sarmiento’s techniques to illustrate his social projection. Those who were isolated and thus opposed to political relations were considered as a symbol of ignorance and anarchy. And this symbol of ignorance and anarchy is once again connected to barbarism, a position in which Argentina was located.[41]

At that time, Sarmiento viewed himself as civilization and Rosas as barbarism. Sarmiento mainly attacked Rosas through his book, Facundo Civilization and Barbarism, which shows the education and “civilized” status. On the other hand Sarmiento used political power to dispose of any kind of hindrance. In other words, Rosas mainly used brute strength to achieve what was needed to achieve while Sarmiento used wits and intelligence to help advance the country. Sarmiento strongly linked Europe to civilization and civilization to education. By doing so, he managed to illustrate an admiration of their culture and civilization. At the same time, it gave the author a sense of dissatisfaction, motivating him move towards civilization/Europe. Europe was connected to civilization which means that Latin America was connected to barbarism. Sarmiento did this mainly to illustrate how Argentina was disconnected to the numerous resources surrounding it, which limited the growth of the country.[42]

Sarmiento's friend, Vicente Fidel Lopez, eliminated the difference of the Latin American cultural shores in his thesis, “Memory on the general results with which the old towns have contributed to the civilization of the humanity” (original quote “memoria sobre los resultados generals con que los pueblos anitiguos han contribuido a la civilización de la humanidad.” ) Sarmiento continues this thesis with a sense of struggle which shows what critic Diana Sorensen Goodrich terms "the progress of the nation in its postcolonial phase."[42] Although the land of Argentina, i.e. geography, and its impact on the socialization work as a boundary to move towards to a civilized society, the historical influence manages to push civilization-barbarism to move forward which gradually bring about in the achievement of civilization.[42] This forward movement is shown in the final chapters of Facundo, where the head of power is removed to continue towards civilization.

This dichotomy is also strongly linked with writing and power which is another main theme in this book since Sarmiento illustrates that education/writing is linked to civil. And those who are ignorant are portrayed as being barbaric.[43]

Dictatorship

In Latin American history, after the independence processes, dictatorships were very common in the region. Even in our days, Hugo Chavez, Augusto Pinochet and Fidel Castro, are examples of one of the most particular characteristics of Latin America. In this context, the literature of this part of the world has been characterized by the protest novel, books in which the main story is around the dictators figure, his behaviors, his main particularities and the situation of the people under this regime. Writers such as Sarmiento, used the power of the word in order to criticize a government by using the literature as a tool, as an instance of the power and as an arm against the repression.[citation needed]

Writing and Power

The connection between writing and power was one of Sarmiento's strategy. For Sarmiento, writing was a catalyst that aroused action. [44]The author used text as a weapon. [45]Sarmiento wanted the book to travel not only in Argentina but also to Europe and United States. His main purpose was to allure the public to his own political view.[46] The numerous translation of the book Facundo is a proof of its travels. Writing was associated with prestige, power and conquest. [47] “Men can have their throats cut, but ideas cannot.” This simple quote shows the superiority Sarmiento felt due to his writing. When Sarmiento was about to leave his homeland, he wrote with charcoal in spanish ¨A los hombres se desguella: a las ideas no.¨ The Spanish used here is physical, graphic and barbaric. The throat cutting displays graphic and crude images, which showed how animalistc/barbaric and vivid the language Spanish can be. [48]

In many of his books, mainly in Facundo, Sarmiento mocks the government therefore elevating his status. He is almost seen as invincible due to the power of writing, despite his physical appearance. When the oppressors fail to understand what was written, Sarmiento is able to illustrate the ineptitude of his oppressor. The written words are displayed as a “code” that needs to be “deciphered,” [48] which shows just how foreign the material was. Unlike Sarmiento, they are barbaric and uneducated. The simple words “what does this mean?” not only demonstrate the ignorance of Rosas’ associates, but also it shows the essential displacement in cultural absence. [49]

Legacy

Facundo has been enormously influential. It is the founding text of Argentine literature but is also more generally, as González Echevarría notes, "the first Latin American classic."[1] This book contributed to many changes in Argentina. Josefina Ludmer marks that Facundo is “the first cathedral of Argentine culture” [original quote, la primera cathedral de la cultura argentina; find translated edition, and provide proper reference][50] Facundo is a founding text. It is also valued as highly important since it marks the beginning of the cultural phenomena. Sorensen mentions that “Facundo has given life to a national literary circuit” due to it’s incredible impact.[51]

The early Facundo readers were deeply motivated and inspired by the information that Sarmiento provided and the struggles that occurred during and after the dictatorship of Rosas. Because of this, their views moved from relationship to the conflict for political hegemony.[52] An empirical proof of Facundo’s, the book, strength is Sarmiento’s rise. He became president of Argentina in 1868. Sarmiento, an educator and writer, used his writing and power to his advantage in order to consolidate the nation. Sorenson states that, “Facundo lends itself admirably to being read as a blueprint for modernization,” which shows the great impact that Facundo and Sarmiento had in Argentina.[53] Sarmiento wrote several books but he viewed Facundo as authorizing his claims to political office.[54]

Publication and translation history

The first and second editions of Facundo were published in 1845 and 1851. The first edition was published, in installments, in the Chilean newspaper El Progreso and was published as part of that paper's literary supplement. The second edition was also published in Chile but with significant changes. [4]

It was first translated, by Mary Mann with the title Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants; or, Civilization and Barbarism in 1868. A modern and more complete translation was undertaken by Kathleen Ross. Her work was published in 2003 by the University of California Press. In Ross' "Translator's Introduction," she notes that Mann's nineteenth-century version of the text, turning it "had much to do with the fact that in 1868 Sarmiento was a candidate for the Argentine presidency" and "Mann wished to further her friend's cause abroad by presenting Sarmiento as an admirer and emulator of United States political and cultural institutions." Hence, this translation cut much of what made Sarmiento's work distinctively part of the Hispanic tradition. As Ross continues, "Mann's elimination of metaphor, the stylistic device perhaps most characteristic of Sarmiento's prose, is especially striking."[55]

Footnotes

- ^ a b González Echevarría 2003, p. 1

- ^ a b c Ross 2003, p. 17

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 177

- ^ a b Ross 2003, p. 18

- ^ a b Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 172

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 171

- ^ a b c d Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 173

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 18

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, pp. 173–174

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 59

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 72

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 78

- ^ a b Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 175

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 105

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 112

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, pp. 175–176

- ^ a b Sarmiento 2003, p. 131

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 133

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 149

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 204

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 227

- ^ "Nunca tomé a Facundo, de Sarmiento, por una obra histórica, ni creo que pueda salir bien librada jugádola en tal respecto. Siempre me pareció una obra literaria, una novela a base histórica." Qtd. Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 42

- ^ Carilla 1973, p. 9

- ^ Carilla 1973, p. 11

- ^ Carilla 1973, p. 12

- ^ a b Sarmiento 2003, p. 93

- ^ Newton 1965, p. 11

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 95

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 94

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 157

- ^ Moss Valestuk 1999, p. 171

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 1

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 11

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 213

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, pp. 213–214

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 215

- ^ Mann 1868, p. 357

- ^ Mann 1868, p. 357

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 35

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 6

- ^ Bravo 1994, p. 487

- ^ a b c Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 9

- ^ Bravo 1994, p. 487

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 25

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 33

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 85

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 27

- ^ a b Sarmiento 2003, p. 30

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 84

- ^ Ludmer 1991, p. 22

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 23

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 64

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 99

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, pp. 100–101

- ^ Ross 2003, p. 19

References

- Bravo, Héctor Félix (1994), "Domingo Faustino Sarmiento" (PDF), Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 24 (3/4), Paris: UNESCO: International Bureau of Education: 487–500, retrieved March 15, 2008.

- Carilla, Emilio (1973), Lengua y estilo en el Facundo, Buenos Aires: Universidad nacional de Tucumán, ISBN 3942402108

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help).

- González Echevarría, Roberto (1985), The Voice of the Masters: Writing and Authority in Modern Latin American Literature, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292787162.

- González Echevarría, Roberto (2003), "Facundo: An Introduction", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 1–16.

- Ludmer, Josefina (1991), The Gaucho Genre: A Treatise on the Motherland, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, ISBN 0822328305. Trans. Molly Weigel.

- Lynch, John (1981), Argentine Dictator: Juan Manuel de Rosas 1829–1852, New York, US: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198211295

- Martínez Estrada, Ezequiel (1969), Sarmiento, Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, ISBN 9508451076.

- Moss, Joyce; Valestuk, Lorraine (1999), "Facundo: Domingo F. Sarmiento", Latin American Literature and Its Times, vol. 1, World Literature and Its Times: Profiles of Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events That Influenced Them, Detroit: Gale Group, pp. 171–180, ISBN 0787637262

- Newton, Jorge (1965), Facundo Quiroga: Aventura y leyenda, Buenos Aires: Plus Ultra, ISBN ??

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

- Ross, Kathleen (2003), "Translator's Introduction", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, trans. Kathleen Ross, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 17–26.

- Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (1868), Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants; Civilization and Barbarism. With a Biographical Sketch of the Author, New York: Hafner Publishing Co.. First published in 1868. Trans. Mrs.Horace Mann.

- Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (2003), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (published 1845), ISBN 0520239806 The first complete English translation. Trans. Kathleen Ross.

- Sorensen Goodrich, Diana (1996), Facundo and the Construction of Argentine Culture, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292727909

External links

- Facundo in the original Spanish