Facundo

| File:Facundo sarmiento.jpg The cover of a recent translation, from the University of California Press. | |

| Author | Domingo Faustino Sarmiento |

|---|---|

| Country | Argentina |

| Language | Spanish |

| Publisher | El Progreso de Chile (first, serial, edition in original Spanish) |

Publication date | 1845 |

Published in English | 1868 (Mary Mann translation) |

| Media type | |

Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism is an 1845 book by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, the seventh president of Argentina. It is a keystone of Latin American literature. Subtitled Civilization and Barbarism, Facundo contrasts civilization and barbarism as seen in early nineteenth-century Argentina and is a commentary on Juan Manuel de Rosas, the dictator who ruled Argentina from 1829 to 1832 and again from 1835 to 1852. The literary critic Roberto González Echevarría calls it "the most important book written by a Latin American in any discipline or genre".[1]

Translator Kathleen Ross argues that Sarmiento published Facundo to "denounce the tyranny of the Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas."[2] Ross further asserts that Sarmiento attacks Rosas by describing the "Argentine national character, explaining the effects of Argentina's geographical conditions on personality, the 'barbaric' nature of the countryside versus the "civilizing" influence of the city, and the great future awaiting Argentina when it opened its doors wide to European immigration."[2]

Facundo describes the life of Juan Facundo Quiroga, a gaucho who exemplifies Argentine culture. He was both a caudillo and a leader of the provincial area of Argentina, and represents barbarism in the countryside.[3] Throughout the text, Sarmiento describes a dichotomy between civilization and barbarism. According to Moss, "civilization is identified with northern Europe, North America, cities, Unitarians, Paz, and Rivadavia."[4] On the other hand, "barbarism is identified with Latin America, Spain, Asia, the Middle East, the countryside, Federalists, Facundo, and Rosas."[5]

Background

In 1845, while exiled in Chile, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento wrote Facundo, now recognized as "one of the foundational works of Spanish American literary history” as translator Ross argues.[6] Sarmiento wrote Facundo in retaliation against his enemies, Juan Facundo Quiroga, a leader in San Juan, and Juan Manuel de Rosas, the Argentine dictator, both of whom Sarmiento refers to as caudillo –individual who rules by his personal charisma rather than with law. [7] Cultural disputes in the Latin American country form the basis on which Facundo was written. Then as now, Buenos Aires was the country’s biggest and wealthiest city as a result of access to the South Atlantic Ocean and rivers. Buenos Aires was exposed not only to the trade, but also to fresh ideas and European culture. Additional differences in culture and ideologies became a cause of tension between the Buenos Aires and the smaller Argentine cities. [citation needed]

Argentine civil war

The Argentine civil war arose in 1826 when Bernardino Rivadavia was elected president of Argentina. Supporters of centralized government challenged the Unitarian Party leading to the outbreak in violence. Federalists Juan Facundo Quiroga and Juan Manuel de Rosas wanted more autonomy for the individual provinces, and were inclined to reject the European culture.[8]

However, the Unitarians defended Rivadavia’s presidency since it created educational opportunities for rural inhabitants through a European-staffed university program. On the other hand, the salaries of the common laborers depended in the government cap and the gauchos were arrested and the majority were forced to work without pay.[9]

A series of governors were installed and replaced beginning in 1827 with the appointment of Federalist Manuel Dorrego as the Buenos Aires governor . When he was overthrown and executed, Unitarian Juan Lavalle replaced Dorrego.[10] His rule lasted until he was defeated by a militia of gauchos led by Rosas. By the end of 1829, the legislature had appointed Rosas as governor of Buenos Aires.[11]

Rosas dictatorship

Juan Manuel de Rosas first time as governor lasted only three years. His rule, with help from Juan Facundo Quiroga and Estanislao Lopez, was respected and he was praised for his ability to maintain harmony between Buenos Aires and the rural areas.[12] When the country fell into disorder after Rosas’ resignation, he was once again called to lead the country. However, he ruled the country not as he did during his first term as governor, but as a dictator and his totalitarian dictatorship forced all the citizens to support the Federalists regime. As Moss argues: "Rosas embraced totalitarianism and forced his citizens to support Federalism and his regime. At that time, all documents, including personal correspondence, had to begin with a phrase that showed support for Rosas's Federalist government. Furthermore, the press was censored and the mazorca (Rosas's vigilante militia) was ordered to patrol the streets to prevent disorder. Rosas's wide-ranging powers enabled him to arrest or imprison anyone, subject them to torture or execution, or have them exiled".[13]

Synopsis

Sarmiento divided Facundo into 15 chapters. It is difficult to classify as belonging to a specific genre, as it combines "history, biography, sociology, geography, poetic description, and political propaganda".[2] It broadly falls into three sections, in which the first (Chapters I to IV) examines Argentine geography and history, the second (Chapters V to XIV) recounts Juan Facundo Quiroga's life, and the third (Chapter XV) expounds on Sarmiento's vision of Argentina's possible future under a Unitarist government.[3] Sarmiento explains the reason why he chose to provide Argentine context and use Facundo Quiroga to condemn Rosas dictatorship is because: "in Facundo Quiroga I do not only see simply a caudillo, but rather a manifestation of Argentine life as it has been made by colonization and the peculiarities of the land."[14]

Argentine Context

This book begins with a geographical description of Argentina. Argentina spread from the east of the Andes to the west of Atlantic Ocean. It consists of a place called Rio de Plata, where river systems in Argentina are converged. By introducing the geography, Sarmiento is able to illustrate that the rivers systems put Buenos Aires at a positive position since the systems would help the country to achieve civilization. Unfortunately, Buenos Aires failed to spread civilization to the rural areas and as a result, Argentina was doomed to barbarism. Also, due to Argentina’s wide and empty plains which are known as pampas, Sarmiento argues that "there was no place for people to escape and hide for defense and this prohibits civilization in most parts of Argentina."[15] Despite Argentina’s land of acting as a barrier, Sarmiento argues that many consequences were mainly caused by Juan Manuel de Rosas, who was a dictator of Argentina at the time, since he managed to take control of Buenos Aires."[16] Sarmiento then continues by introducing the four main types of gaucho: "rastreador", "baqueano", the bad "gaucho", and the "cantor". By mentioning the four different types of gaucho, he spreads awareness and understanding of Argentine leaders, such as Juan Manuel de Rosas."[17] He argues that "without which it is impossible to understand our political personages, or the primordial, American character of the bloody struggle that tears apart the Argentine Republic."[18]

Sarmiento then continues the book by displaying the Argentine peasants, who are "independent of all need, free of all subjection, with no idea of government."[19] The peasants turn their gatherings at a tavern, a place where they spend their time drinking and gambling. They display their eagerness to prove their physical strength through various activities, mainly horsemanship and knife fight. However, killings happened rarely when the gauchos demonstrated their skills. Before Juan Manuel de Rosas rise to power in Argentina, his residence was used as a refuge when killings took place."[20]

According to Sarmiento, all of these were crucial to help the readers to understand the Argentina Revolution in which Argentina gained independence from Spain. Although Argentina’s independence war was aroused by European thoughts, Buenos Aires was the only city that could achieve and obtain civilization. The inhabitants in the countryside participated in the war to demonstrate their physical strengths instead of helping to achieve civilization. Therefore in the end, the revolution was a failure because, by following their animalistic instincts, they have lost and dishonored the civilized cities."[21]

Life of Juan Facundo Quiroga

Juan Facundo Quiroga who was also called "The tiger of the Plains",[22] was born into a wealthy family but he never received a good education. He loved gambling and his antisocial and rebellious character caused him to break off of relations with his family. Then, Facundo became into a gaucho and joined the caudillos in the Entre los Rios province."[23]

His popularity began to rise as he killed two Spaniards after his jailbreak and became a hero among other gauchos. Later, in La Rioja, Facundo was named sergeant major of the Llanos Militia. He gained reputation and respect from his people by fighting fiercely in battles. However, due to his antisocial character, he hated and would destroy people who people who were civilized and educated (i.e. people who do not have the same characters as him)"[24]

Sarmiento then illustrates the dichotomy of civilization and barbarism in two cities, Buenos Aires and Córdoba, before resuming his biography of Facundo. In 1825, when Bernardino Rivadavia (a Federalist) became the governor of the Buenos Aires province, he held a meeting with all the representatives from all provinces in Argentina. Facundo was there as the governor of La Rioja."[25] During a revolution in which Rivadavia was overthrown, Manuel Dorrego became the new governor. However, Dorrego was not concerned about progression of the society nor putting barbarisms to an end for Argentina. Facundo was defeated by General Paz (a Unitarist) after the Unitarists assassinated Dorrego." [26] Facundo escaped to Buenos Aires and joined the Federalist government of Rosas. During the civil war between Federalists and Unitarians, Facundo conquered the San Luis, Rio Quinto and Mendoza provinces."[27]

When Facundo came back to San Juan, he realized that his government did not have support from Rosas. Thus, he went to Buenos Aires to face Rosas but he was sent to another mission by Rosas. On his way to the place where he was assigned to complete the mission, he was killed by a shot."[28] According to Sarmiento, the murder was plotted by Rosas: "An impartial history still awaits facts and revelations, in order to point its finger at the instigator of the assassins"."[29]

Consequences of Facundo's Death

In the final chapters, Sarmiento delves into the consequences that derived from Facundo's death for the history and politics of the Argentine Republic.[30] He further analyzes Rosas's government, commenting on dictatorship, tyranny, the use of force to maintain order and stability, the support of the people, and Rosas's personality. Sarmiento criticizes Rosas by using the words of the dictator, making sarcastic remarks about what Rosas was doing and describing the "terror" that was established during the dictatorship, the contradictions of the government and the situation in the provinces that were ruled by Facundo: "The red ribbon is a materialization of the terror that accompanies you everywhere, in the streets, in the bosom of the family; it must be thought about when dressing, shen undressing, and ideas are always engraved upon us by association".[31]

Finally, Sarmiento examines the consequences of Rosas's government by attacking the dictator and establishing a bigger dichotomy. By setting France, symbolizing civilization, against Argentina, representing barbarism, Sarmiento contrasts culture and savagery:

"France's blockade had lasted for two years, and the 'American' government, inspired by 'American' spirit, was facing off with France, European principles, European pretensions. The social results of the French blockade, however, had been fruitful for the Argentine Republic, and served to demonstrate in all their nakedness the current state of mind and the new elements of struggle, which were to ignite a fierce war than can end only with the fall of that monstrous government."[32]

Main Characters

Facundo

Juan Facundo Quiroga is the book's protagonist. He is called the "Tiger of the Plains",[33] and is described as being "el jugador", meaning the player.[34] He loves to gamble, to the point where gambling is described for him as "an ardent passion burning in his belly".[35] Portrayed as wild and untamed, Facundo is a normal caudillo of the period. He had a narrow education, only learning to read and write. Through him Sarmiento demonstrates that the caudillos were more barbaric than civilized, linking to one of the themes of his book.

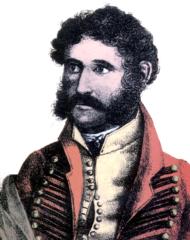

During his childhood, Facundo is portrayed as being "arrogant, disdainful and solitary." [36] At the time of his rise to El General, he is described as being of a short with a muscular stature, strong shoulders with a short neck sustaining his slightly elliptical face. His features are typical of a caudillo at that time, with thick curly hair and a black beard. Hidden in his abundant and hairy eyebrows, "his eyes were filled with passion and wilderness", a key element that terrified many. [33] According to Sarmiento, "Quiroga governed San Juan solely with his terrifying name."[37]

Juan Manuel de Rosas

Sarmiento intended Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism as a critique of the dictator Rosas, during whose rule Facundo was written.

According literary critic John Lynch, "Juan Manuel de Rosas was a landowner, a rural caudillo, and the dictator of Buenos Aires from 1829 to 1852."[38] "He was born into a wealthy, high status family, but his harsh mother had a huge influence on his development."[39] Sarmiento argues that because of his mother, "the spectacle of authority and servitude must have left lasting impressions on him."[40] Banished to an estancia by his father when he was barely into puberty, Rosas remained there for almost thirty years. By 1824 he had established an authoritarian style in dealing with matters regarding the estancias, and had introduced a harsh regime. Sarmiento points out that this is the type of regime he later tried out in Buenos Aires.[41] In government, Rosas imprisoned many citizens for unknown reasons, and for long periods, which was much like the roundup in which cattle were tamed and enclosed inside the corral. Sarmiento also argues that the whippings in the street and the massacres were his methods of making his citizens like the "tamest, most orderly cattle known."[42]

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

In Facundo, Sarmiento is both the narrator and a main character. The book contains autobiographical elements from Sarmiento’s life, and he comments on the entire Argentine situation. He also analyses and expresses his own opinion, as well as chronicling some historic events. In the book's dichotomy between civilization and barbarism, Sarmiento's character represents civilization, steeped as he is in European and North American ideas. He stands for education and development, as opposed to both Rosas and Facundo, who symbolise barbarism.

In real life, Sarmiento was an educator, a civilized man who was a militant adherent to the Unitarian movement. During the Argentine civil war he fought against Facundo several times, and while in Spain became a member of the Literary Society of Professors.[43] Exiled to Chile by Rosas when he started to write Facundo, Sarmiento would later return as a politician. He was member of the Senate after Rosas's fall, and was president of Argentina for six years (1868–1874). During his presidency, Sarmiento concentrated on migration, sciences, and culture. His ideas were based on European civilization; for him, the development of a country was rooted in education. To this end, he founded Argentina's military and naval colleges.[44]

Genre and style

Spanish critic and philosopher Miguel de Unamumo argues: "I never took Facundo by Sarmiento, as a historical work, nor do I think it can be very valued in that regard. I always thought of it as a literary work, as a historical novel."[45] However, Facundo cannot be classified either as a novel or as a specific genre of literature. According to González Echevarría, the book is an "essay, biography, autobiography, novel, epic, memoir, confession, political pamphlet, diatribe, scientific treatise, travelogue" at the same time.[46] Sarmiento's style unifies the three distinct portions of his work, and the common thread is the life of Juan Facundo Quiroga. Even the first section, describing Argentina's geography, follows this pattern, since Sarmiento contends that Facundo is a natural product of this environment.[47]

Furthermore, the book is a combination between the fiction and the real context of the Argentinean Republic. In the book, Rosas has characteristics of both, the real life and the imagination of Sarmiento. Because the book is criticizing the government, the dictatorship is seen as the main cause of all the problems in Argentina, therefore, the barbarism and the savagism that Sarmiento is explaining in all the book, is a function of the dictatorship. .[48]

Themes

Civilization and barbarism

More than just a critique of Rosas's dictatorship, Facundo is also a broader investigation into Argentine history and culture, which Sarmiento charts through the rise, controversial rule, and downfall of Juan Facundo Quiroga, an archetypical Argentine caudillo. Sarmiento summarizes the book's message in the phrase: "That is the point: to be or not to be savages."[49] This dichotomy, between civilization and barbarism, is the book's central idea; Facundo Quiroga is portrayed as wild, untamed, and as standing in opposition to true progress through the common enlightenment of European society—found at that time in the metropolitan society of Buenos Aires.[50]

The conflict between civilization and barbarism mirrors Latin America's difficulties faced in the post-Independence era. Sorensen argues that, although Sarmiento was not the one to create this dichotomy, he managed to turn it into an powerful and prominent concept that would impact on future Latin America Literature.[51] He explores the issue of civilization versus the cruder aspects of a caudillo culture of brutality and absolute power. Caudillos like Facundo Quiroga are seen, at the beginning of the book, as the antithesis of education, high culture, and civil stability. They are the agents of instability and chaos, destroying societies through their blatant disregard for humanity and social progress.[52]

As caudillos took control of Argentina and other Latin American countries, establishing authoritarian governments, questions of what was best for the progress of society were largely ignored by the ruling elites in preference for the immediate goal of exploiting the masses. Facundo set forth an opposition message that promoted a more beneficial alternative for society at large. Although Sarmiento advocated various changes, such as honest officials who understood enlightenment ideas of European and Classical origin, for him education was the essential key. He viewed barbarism, linked with ignorance, poverty, lack of education and anarchy, as a never-ending litany of social ills.[53] He used the pampas wilderness described in Facundo to illustrate his social analysis; those who were isolated and opposed to political dialogue were symbols of ignorance and anarchy, a reflection of Argentina's desolate physical geography.[53]

If Sarmiento viewed himself as civilized, Rosas was barbaric. Literary critic David Rock argues that "contemporary opponents reviled Rosas as a bloody tyrant and a symbol of barbarism."[54] Sarmiento attacked Rosas through his book by promoting education and "civilized" status, while using political power to dispose of any kind of hindrance. In linking Europe with civilization, and civilization with education, Sarmiento conveyed an admiration of European culture and civilization which at the same time gave him a sense of dissatisfaction with his own culture, motivating him to drive it towards civilization. Conversely Latin America was connected to barbarism, which Sarmiento used mainly to illustrate the way in which Argentina was disconnected from the numerous resources surrounding it, which limited the growth of the country.[55]

Writing and Power

In post-independence Latin American history, dictatorships have been relatively common—Manuel Noriega, Augusto Pinochet, Fidel Castro and Alfredo Stroessner are among the region's more notable examples. In this context, Latin American literature has been distinguished by the protest novel; the main story is based around the dictator figure, his behavior, characteristics and the situation of the people under his regime. Writers such as Sarmiento used the power of the written word in order to criticize government, using literature as a tool, an instance of resistance and as a weapon against repression.[48]

Making use of the connection between writing and power was one of Sarmiento's strategies. For him, writing was a catalyst that aroused action.[56] While the gauchos fought with physical weapons, Sarmiento used his voice and language.[57] Sorensen strongly states that the text he wrote was his choice of weapon.[48] Sarmiento wanted his book to gain an audience, not only in Argentina, but also in many places, especially United States and Europe since these countries were close to civilization;his purpose was to seduce his readers toward his own political point of view.[58] The numerous translations of Facundo are proof of this concept; for Sarmiento, writing was associated with power, and conquest.[59]

Sarmiento mocks the government in many of his books, although Facundo is the most overt example. He elevates his own status at the expense of the ruling elite, almost portraying himself as invincible due to the power of writing. Toward the end of 1840, Sarmiento was exiled. Covered with bruises received the day before from unruly soldiers, he wrote in French "On ne tue point les idees" (misquoted from "on ne tue pas de coups de fusil aux idees", which means "ideas cannot be killed by guns"). The government decided to decipher the message, and on learning the translation, said "So! What does this mean?"[60] With the failure of his oppressors to understand his meaning, Sarmiento is able to illustrate their ineptitude. His written words are presented as a "code" that needs to be "deciphered".[60] Unlike Sarmiento, those in power are barbaric and uneducated, and their bafflement not only demonstrates the ignorance of Rosas’ associates, but also, according to Sorensen, illustrates "the fundamental displacement whicn any cultural transplantation brings about," since Argentine rural inhabitants and Rosas' associates were unable to accept the civilized culture which Sarmiento believed would lead to the progression of Argentina.[61]

Legacy

Facundo has been enormously influential because of its strong ability guidance to reach modernization. Also the prose style which is complemented by "tremendous beauty and passion," [citation needed] support the argument that this book is able to summon changes in Argentina, which makes Facundo is a powerful founding text.[2] Not only is it the founding text of Argentine literature but, according to literary critic González Echevarría: "It is the first Latin American classic, and the most important book written about Latin America by a Latin American in any discipline or genre." [62] He argues that "in proposing the dialect between civilization and barbarism as the central conflict in Latin American culture it gave shape to a polemic that began in the colonial period and continues to the present day in various guises."[1] He asserts that Facundo provided the impetus for other writers to examine dictatorship in Latin America. Moreover, González Echevarría explains that Facundo is still read today since Sarmiento created "a voice for modern Latin American authors". [63] He argues that the reason for this is that "Latin American authors struggle with its legacy, rewriting Facundo in their works even as they try to untangle themselves from its discourse."[46] Subsequent dictator novels, such as El Señor Presidente by Miguel Ángel Asturias and The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa, were influenced by its publication.[46] A knowledge of Facundo boosts and expands the reader’s understanding of these later books.[64]

According to González Echevarría, due to the impact of Sarmiento essay genre and fictional literature, the gaucho has become "an object of nostalgia, a lost origin around which to build a national mythology."[64] However, he also argues that Juan Facundo Quiroga continues to exist, since he represents "our unresolved struggle between good and evil and our lives' inexorable drive toward death."[64] When Sarmiento was trying to eliminate the gaucho, this caused to transform Facundo into a "national symbol." [64] According to translator Kathleen Ross, "Facundo continues to inspire controversy and debate because it contributes to national myths of modernization, anti-populism, and racist ideology."[65]

According to Sorensen, "early readers of Facundo were deeply influenced by the struggles that preceded and followed Rosas's Dictatorship, and their views sprang from their relationship to the strife for interpretive and political hegemony".[66] An empirical proof of the book's influence is the fact of Sarmiento’s rise to power. He became president of Argentina in 1868—an educator and writer, he used his skills to his advantage in order to unite and therefore ensure that the nation achieves civilization. Sorenson argues that "Facundo lends itself admirably to being read as a blueprint for modernization" [67] and it is underlined by the great impact that the book and its author had in Argentina. [67] Sarmiento wrote several books, but he viewed Facundo as authorizing his political views.[68]

Publication and translation history

The first edition of Facundo was published in instalments in 1845, in the literary supplement of the Chilean newspaper El Progreso. The second edition, also published in Chile (in 1851), contained significant alterations—Sarmiento removed the last two chapters on the advice of Valentín Alsina, an exiled Argentinian lawyer and politician.[3] However the missing sections reappeared in 1874 in a later edition, because Sarmiento saw them as crucial to the development of the book.[69]

Facundo was first translated in 1868, by Mary Mann, with the title Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants; or, Civilization and Barbarism. Recently Kathleen Ross has undertaken a modern and complete translation, published in 2003 by the University of California Press. In Ross's "Translator's Introduction," she notes about Mann's nineteenth-century version of the text that it "had much to do with the fact that in 1868 Sarmiento was a candidate for the Argentine presidency" and "Mann wished to further her friend's cause abroad by presenting Sarmiento as an admirer and emulator of United States political and cultural institutions." Hence this translation cut much of what made Sarmiento's work distinctively part of the Hispanic tradition. Ross continues: "Mann's elimination of metaphor, the stylistic device perhaps most characteristic of Sarmiento's prose, is especially striking."[70]

Footnotes

- ^ a b González Echevarría 2003, p. 1

- ^ a b c d Ross 2003, p. 17

- ^ a b c Ross 2003, p. 18

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 177

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 177

- ^ Ross 2003, p. 17

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 171

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 172

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 172

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 172-173

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 173

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 173

- ^ Moss & Valestuk 1999, p. 179

- ^ <sarmiento pg.38>

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 1

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 2

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 3

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 71

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 72

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 3

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 4

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 93

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 5

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 6

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 7 and 8

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 8 and 9

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 11 and 12

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. Chapter 13

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 204

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 227

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 210

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 228

- ^ a b Sarmiento 2003, p. 93

- ^ Newton 1965, p. 11

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 95

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 94

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 157

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 1

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 11

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 213

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, pp. 213–214

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 215

- ^ Mann 1868, p. 357

- ^ González Echevarría 2003, p. 10

- ^ Qtd. Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 42

- ^ a b c González Echevarría 2003, p. 2

- ^ Carilla 1973, p. 12

- ^ a b c Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 33

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 35

- ^ Sarmiento 2003, p. 99

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 6

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 8

- ^ a b Bravo 1994, p. 487

- ^ Ludmer 2002, p. 7

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 9

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 25

- ^ Ludmer 2002, p. 9

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 85

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 27

- ^ a b Sarmiento 2003, p. 30

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 84

- ^ <gonzalez echevarria pg.1>

- ^ <gonzalez echevarria pg.2>

- ^ a b c d González Echevarría 2003, p. 15

- ^ Ross 2003, p. 21

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 67

- ^ a b Sorensen Goodrich 1996, p. 99

- ^ Sorensen Goodrich 1996, pp. 100–101

- ^ Carilla 1973, p. 13

- ^ Ross 2003, p. 19

References

- Bravo, Héctor Félix (1994), "Domingo Faustino Sarmiento" (PDF), Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 24 (3/4), Paris: UNESCO: International Bureau of Education: 487–500, retrieved March 15, 2008.

- Carilla, Emilio (1973), Lengua y estilo en el Facundo, Buenos Aires: Universidad nacional de Tucumán, ISBN 3942402108

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help).

- González Echevarría, Roberto (1985), The Voice of the Masters: Writing and Authority in Modern Latin American Literature, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292787162.

- González Echevarría, Roberto (2003), "Facundo: An Introduction", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 1–16.

- Ludmer, Josefina (2002), The Gaucho Genre: A Treatise on the Motherland, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, ISBN 0822328445. Trans. Molly Weigel.

- Lynch, John (1981), Argentine Dictator: Juan Manuel de Rosas 1829–1852, New York, US: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198211295

- Martínez Estrada, Ezequiel (1969), Sarmiento, Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, ISBN 9508451076.

- Moss, Joyce; Valestuk, Lorraine (1999), "Facundo: Domingo F. Sarmiento", Latin American Literature and Its Times, vol. 1, World Literature and Its Times: Profiles of Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events That Influenced Them, Detroit: Gale Group, pp. 171–180, ISBN 0787637262

- Newton, Jorge (1965), Facundo Quiroga: Aventura y leyenda, Buenos Aires: Plus Ultra, ISBN unavailable

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

- Ross, Kathleen (2003), "Translator's Introduction", in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (ed.), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, trans. Kathleen Ross, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 17–26.

- Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (1868), Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants; Civilization and Barbarism. With a Biographical Sketch of the Author, New York: Hafner Publishing Co.. First published in 1868. Trans. Mrs.Horace Mann.

- Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino (2003), Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (published 1845), ISBN 0520239806 The first complete English translation. Trans. Kathleen Ross.

- Sorensen Goodrich, Diana (1996), Facundo and the Construction of Argentine Culture, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292727909

External links

- Facundo in the original Spanish