James Russell Lowell

James Russell Lowell | |

|---|---|

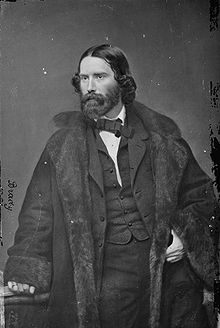

James Russell Lowell circa 1855. | |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

James Russell Lowell (February 22, 1819, Cambridge, Massachusetts – August 12, 1891, Cambridge, Massachusetts) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets.

Lowell graduated from Harvard College in 1838, despite his reputation as a troublemaker, and went on to earn a law degree from Harvard Law School. He published his first collection of poetry in 1841 and married Maria White in 1844. He and his wife soon become involved in abolitionism, with Lowell expressing his stance in his poetry and taking a job in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as editor of an abolitionist newspaper. He and Maria White had several children, though only one survived past childhood. After moving back to Cambridge, Lowell was one of the founders of a journal called The Pioneer, which lasted only three issues. He gained notoriety in 1848 with the publication of A Fable for Critics, a book-length poem satirizing contemporary critics and poets. The same year, he published The Biglow Papers, which increased his fame. He would publish several other poetry collections and essay collections throughout his literary career.

Maria White died in 1853 and Lowell accepted a professorship of languages at Harvard in 1854. He traveled to Europe before officially assuming his role in 1856, which he held for twenty years. He married his second wife, Frances Dunlap, shortly thereafter in 1857. That year Lowell also became editor of The Atlantic Monthly. It was not until 20 years later that Lowell received his first political appointment: the ambassadorship to Spain and, later, to England. He spent his last years in Cambridge, in the same estate where he was born, where he also died in 1891.

Lowell believed that the poet played an important role as a prophet and critic of society. He used his poetry, in part, for reform, particularly in abolitionism. However, Lowell's commitment to the anti-slavery cause wavered over the years, as did his opinion on African-Americans. Lowell attempted to emulate the true Yankee accent in the dialogue of his characters, particularly in The Biglow Papers. This depiction of the dialect, as well as Lowell's many satires, were an inspiration to writers like Mark Twain and H. L. Mencken. Nevertheless, Lowell's poetry has been criticized by many its lack of force, its poor quality, and for being forgettable.

Biography

Early life

The first of the Lowell family ancestors to come to the United States from Britain was Percival Lowle, who settled in Newbury, Massachusetts in 1639.[1] James Russell Lowell was born February 22, 1819,[2] the son of the Rev. Charles Russell Lowell, Sr. (1782–1861), a minister at a Unitarian church in Boston who had previously studied theology at Edinburgh, and Harriett Brackett Spence Lowell.[3] By the time James Russell Lowell was born, the family owned a large estate in Cambridge called Elmwood.[4] He was the youngest of six children; his older siblings were Charles, Rebecca, Mary, William, and Robert.[5] Lowell's mother built in him an appreciation for literature at an early age, especially in poetry, ballads, and tales from her native Orkney.[3] He attended school under Sophia Dana, who would later marry George Ripley, and, later, studied at a school run by a particularly harsh disciplinarian, where one of his classmates was Richard Henry Dana, Jr.[6]

Beginning in 1834, at the age of 15, Lowell attended Harvard College, though he was not a good student and often got into trouble.[7] His sophomore year alone, he was absent from required chapel attendance fourteen times and from classes fifty-six times.[8] In his last year there, he wrote, "During Freshman year, I did nothing, during Sophomore year I did nothing, during Junior year I did nothing, and during Senior year I have thus far done nothing in the way of college studies".[7] His senior year, he became one of the editors of Harvardiana literary magazine, to which he contributed prose and poetry that he admitted was of low quality. As he said later, "I was as great an ass as ever brayed & thought it singing".[9] Lowell was elected the poet of the class of 1838[10] and, as was tradition, was asked to recite an original poem on Class Day, the day before Commencement, on July 17, 1838.[8] Lowell, however, was suspended and not allowed to participate. Instead, his poem was printed and made available thanks to subscriptions paid by his classmates.[10]

Not knowing what vocation to choose, he vacillated among business, the ministry, medicine and law. Having decided to practice law, he enrolled at the Harvard Law School in 1840 and was admitted to the bar two years later.[11] While studying law, however, he contributed poems and prose articles to various magazines. During this time, Lowell was admittedly depressed and often had suicidal thoughts. He once confided to a friend that he held a cocked pistol to his forehead and considered killing himself at the age of 20.[12]

Marriage and family

In late 1839, Lowell met Maria White through her brother William, a classmate of his at Harvard.[13] The two became engaged in the autumn of 1840; her father Abijah White, a wealthy merchant from Watertown, insisted that their wedding be postponed until Lowell had gainful employment.[14] They were finally married on December 26, 1844,[15] shortly after the groom published Conversations on the Old Poets, a collection of previously-published essays.[16] A friend described their relationship as "the very picture of a True Marriage";[17] Lowell himself believed the was made up "half of earth and more than of Heaven".[14] Like Lowell, she wrote poetry and the next twelve years of Lowell's life were deeply affected by her influence. He said his first book of poetry, A Year's Life (1841), "owes all its beauty to her", though it only sold 300 copies.[14] Her character and beliefs led her to become involved in the movements directed against intemperance and slavery. White was a member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and convinced Lowell to become an abolitionist.[18] Lowell had previously expressed antislavery sentiments but White urged him towards more active expression and involvement.[19] His second volume of poems, Miscellaneous Poems, expressed these antislavery thoughts and its 1,500 copies sold well.[20]

Maria was in poor health and, thinking her lungs could heal there, the couple moved to Philadelphia shortly after their marriage.[21] In Philadelphia, he became a contributing editor for the Pennsylvania Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper.[22] In the spring of 1845, the Lowells returned to Cambridge to make their home at Elmwood and had four children, though only one survived past infancy. Their first, Blanche, was born December 31, 1845, but lived only fifteen months; Rose, born in 1849, survived only a few months as well; their only son, Walter, was born in 1850 but died in 1852.[23] Lowell was very affected by the loss of almost all of his children. His grief over the loss of his first daughter in particular was expressed in his poem "The First Snowfall" (1847).[24] Again, Lowell considered suicide, writing to a friend that he thought "of my razors and my throat and that I am a fool and a coward not to end it all at once".[23]

Literary career

Lowell's earliest poems were published without pay in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1840.[25] Lowell was inspired to new efforts towards self-support and joined with his friend Robert Carter in founding a literary journal, The Pioneer.[17] The periodical was characterized by most of its content being new rather than previously-published elsewhere and by having very serious criticism which covered not only literature but also art and music.[26] Lowell wrote that it would "furnish the intelligent and reflecting portion of the Reading Public with a rational substitute for the enormous quantity of thrice-diluted trash, in the shape of namby-pamby love tales and sketches, which is monthly poured out to them by many of our popular Magazines".[17] William Wetmore Story noted the journal's higher taste, writing that, "it took some stand & appealled to a higher intellectual Standard than our puerile milk o watery namby-pamby Mags with which we are overrun".[27] The first issue of the journal included the first appearance of "The Tell-Tale Heart" by Edgar Allan Poe.[28] Lowell, shortly after the first issue, was treated for an eye disease in New York and, in his absence, Carter did a poor job managing the journal.[20] After three monthly numbers, beginning in January 1843, the magazine ceased publication, leaving Lowell $1,800 in debt.[28] Poe mourned the journal's demise, calling it "a most severe blow to the cause—the cause of a Pure Taste".[27]

Despite the failure of The Pioneer, Lowell continued his interest in the literary world. He wrote a series on "Anti-Slavery in the United States" for the London Daily News, though it was discontinued by the editors after four articles in May 1846.[29] Lowell had published these articles anonymously, believing they would have more impact if they were not known to be the work of a committed abolitionist.[30] In the spring of 1848 he formed a connection with the National Anti-Slavery Standard of New York, agreeing to contribute weekly either a poem or a prose article. He was asked to contribute half as often to the Standard after only one year to make room for contributions from Edmund Quincy.[31]

Fame as a satirist

A Fable for Critics, one of his most popular works, was published in 1848. A satire, Lowell published it anonymously and took good-natured jabs at his contemporary poets and critics. It proved popular, and the first three thousand copies sold out quickly.[32] Not all the subjects included were pleased, however. Edgar Allan Poe, who had been referred to as part genius and "two-fifths sheer fudge", reviewed the work in the Southern Literary Messenger and called it "'loose'—ill-conceived and feebly executed, as well in detail as in general... we confess some surprise at his putting forth so unpolished a performance".[33] Lowell offered the profits from the book's success, which proved relatively small, to his New York friend Charles Frederick Briggs, despite his own financial needs.[32]

In 1848, Lowell also published The Biglow Papers, later named by the Grolier Club as the most influential book of 1848.[34] The first 1,500 copies sold out within a week and a second edition was soon issued, though Lowell made no profit having had to absorb the cost of stereotyping the book himself.[35] The book presented three main characters, each representing different aspects of American life and using authentic American dialects in their dialogue.[36] Under the surface, The Biglow Papers was also a denunciation of the Mexican–American War and war in general.[37]

First trip to Europe

In 1850, Lowell's mother died unexpectedly, as did his third daughter, Rose. For six months, Lowell became depressed and reclusive, despite the birth of his son Walter by the end of the year. He wrote to a friend that death "is a private tutor. We have no fellow-scholars, and must lay our lessons to heart alone".[38] These personal troubles as well as the Compromise of 1850 inspired Lowell to accept an offer from William Wetmore Story to spend a winter in Italy.[39] To pay for the trip, Lowell sold land around Elmwood, intending to sell off further acres of the estate over time to supplement his income, ultimately selling off 25 of the original 30 acres.[40] Walter died suddenly in Rome of cholera, and Lowell and his wife, with their daughter Mabel, returned to the United States in October 1852.[41] Lowell published some recollections of his journey in several magazines, many of which would be collected years later as Fireside Travels (1867). He also edited volumes with biographical sketches for a series on British Poets.[42]

His wife Maria, who had been suffering from poor health for many years, became very ill in the spring of 1853 before finally dying on October 27[43] of tuberculosis.[23] Just before her burial, her coffin was opened so that her daughter Mabel could see her face while Lowell "leaned for a long while against a tree weeping", according to the Longfellows, who were in attendance.[44] In 1855, Lowell oversaw the publication of a memorial volume of his wife's poetry, with only fifty copies for private circulation.[42] Despite his self-described "naturally joyous" nature,[45] life for Lowell at Elmwood was further complicated by his father becoming deaf in his old age and the deteriorating mental disorder of his sister Rebecca, who sometimes went a week without speaking.[46] He again cut himself off from others, becoming reclusive at Elmwood and his private diaries from this time period are riddled with the initials of his wife.[47] On March 10, 1854, for example, he wrote: "Dark without & within. M.L. M.L. M.L."[48] His friend and neighbor Henry Wadsworth Longfellow referred to him as "lonely and desolate".[49]

Professorship and second marriage

At the invitation of his cousin John Amory Lowell, James Russell Lowell was asked to deliver a lecture at the prestigious Lowell Institute.[50] Some speculated the offer was because of the family connection as an attempt to bring him out of his depression.[51] Lowell chose to speak on "The English Poets", telling his friend Briggs that he would take revenge on dead poets "for the injuries received by one whom the public won't allow among the living".[50] The first of the twelve-part lecture series was to be on January 9, 1855, though by December, Lowell had only completed writing five of them, hoping for last-minute inspiration.[52] His first lecture was on John Milton and the auditorium was oversold, and Lowell had to give a repeat performance the next afternoon.[53] Lowell, who had never spoken in public before, was praised for these lectures. Francis James Child said that Lowell, who he deemed was typically "perverse", was able to "persist in being serious contrary to his impulses and his talents".[52] While his series was still in progress, Lowell was offered the Smith Professorship of Modern Languages at Harvard, a post vacated by Longfellow, at an annual salary of $1,200, though he never applied for it.[54] The job description was changing after Longfellow; instead of teaching languages directly, Lowell would supervise the department deliver two lecture courses per year on topics of his own choosing.[55] Lowell accepted the appointment, with the proviso that he should have a year of study abroad. He set sail on June 4 of that year,[56] leaving his daughter Mabel in the care of a governess named Frances Dunlap.[54] Abroad, he visited Le Havre, Paris, and London, spending time with friends including Story, Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Leigh Hunt. Primarily, however, Lowell spent his time abroad studying languages, particularly German, which he found difficult. He complained: "The confounding genders! If I die I shall have engraved on my tombstone that I died of der, die, das, not because I caught them but because I couldn't."[56]

He returned to the United States in the summer of 1856 and began his college duties.[57] Towards the end of his professorship, then-president of Harvard Charles Eliot Norton noted that Lowell seemed to have "no natural inclination" to teach; Lowell agreed, but retained his position for twenty years.[58] He focused on teaching literature, rather than etymology, hoping that his students would learn to enjoy the sound, rhythm, and flow of poetry rather than the technique of words.[59] He summed up his method: "True scholarship consists in knowing not what things exists, but what they mean; it is not memory but judgment".[60] Still grieving the loss of his wife, during this time Lowell avoided Elmwood and instead lived on Kirkland Street in Cambridge, an area known as Professors' Row. He stayed there, along with his daughter Mabel and her governess Frances Dunlap, until January 1861.[61]

Lowell had intended never to remarry after the death of his wife Maria White. However, in 1857, surprising his friends, he became engaged to Frances Dunlap, who many described as simple and unattractive.[62] Dunlap, daughter of the former governor of Maine Robert P. Dunlap,[63] was a friend of Lowell's first wife and formerly wealthy, though she and her family had fallen into reduced circumstances.[54] Lowell and Dunlap married on September 16, 1857, in a ceremony performed by his brother.[64] Lowell wrote, "My second marriage was the wisest act of my life, & as long as I am sure of it, I can afford to wait till my friends agree with me".[57]

The war years and beyond

In the autumn of 1857, The Atlantic Monthly was established, and Lowell was its first editor. With its first issue in November of that year, he at once gave the magazine the stamp of high literature and of bold speech on public affairs.[65] In January 1861, Lowell's father died of a heart attack, inspiring Lowell to move his family back to Elmwood. As he wrote to his friend Briggs, "I am back again to the place I love best. I am sitting in my old garret, at my old desk, smoking my old pipe... I begin to feel more like my old self than I have these ten years".[66] Shortly thereafter, in May, he left The Atlantic Monthly when James Thomas Fields took over as editor; the magazine had been purchased by Ticknor and Fields for $10,000 two years before.[67] Lowell returned to Elmwood by January 1861 but maintained an amicable relationship with the new owners of the journal, continuing to submit his poetry and prose for the rest of his life.[66] His prose, however, was more abundantly presented in the pages of The North American Review during the years 1862–1872. For the Review, he served as a coeditor along with Charles Eliot Norton.[68] Lowell's reviews for the journal covered a wide variety of literary releases of the day, though he was writing fewer poems.[69]

As early as 1845, Lowell had predicted the debate over slavery would lead to war[70] and, as the American Civil War broke out in the 1860s, Lowell used his role at the Review to praise Abraham Lincoln and his attempts to maintain the Union.[68] Lowell lost three nephews during the war, including Charles Russell Lowell, Jr, who became a Brigadier General and fell at the battle of Cedar Creek. Lowell himself was generally a pacifist. Even so, he wrote, "If the destruction of slavery is to be a consequence of the war, shall we regret it? If it be needful to the successful prosecution of the war, shall anyone oppose it?"[71] His interest in the Civil War inspired him to write a second series of The Biglow Papers,[66] including one specifically dedicated to the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation called "Sunthin' in the Pastoral Line" in 1862.[72]

Shortly after Lincoln's assassination, Lowell was asked to present a poem at Harvard in memory of graduates killed in the war. His poem, "Commemoration Ode", cost him sleep and his appetite, but was delivered July 21, 1865,[73] after a 48-hour writing binge.[74] Lowell had high hopes for his performance but was overshadowed by the other notables presenting works that day, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. "I did not make the hit I expected", he wrote, "and am ashamed at having been tempted again to think I could write poetry, a delusion from which I have been tolerably free these dozen years".[75] Despite his personal assessment, friends and other poets sent many letters to Lowell congratulating him. Emerson referred to its "high thought & sentiment" and James Freeman Clarke noted its "grandeur of tone".[76] Lowell later expanded it with a strophe to Lincoln.[74]

Shortly after serving as a pallbearer at the funeral of friend and publisher Nathaniel Parker Willis, on January 24, 1867,[77] Lowell decided to collect another collection of his poetry. Under the Willows and Other Poems was released in 1869,[69] though Lowell originally wanted to title it The Voyage to the Vinland and Other Poems. The book, dedicated to Norton, collected poems Lowell had written within the previous twenty years and was his first poetry collection since 1848.[78]

Lowell intended to take another trip to Europe. To finance it, he sold off more of Elmwood's acres and rented the house to Thomas Bailey Aldrich; Lowell's daughter Mabel, by this time, had moved into a new home with her husband Edward Burnett, the son of a successful businessman-farmer from Southboro, Massachusetts.[79] Lowell and his wife set sail on on July 8, 1872,[80] after he took a leave of absence from Harvard. They visited England, Paris, Switzerland, and Italy. While overseas, he received an honorary Doctorate of Law from University of Oxford and another from Cambridge University. They returned to the United States in the summer of 1874.[79]

Political appointments

Lowell resigned from his Harvard professorship in 1874, though he was convinced to continue teaching through 1877.[58] It was in 1876 that Lowell first stepped into the field of politics. That year, he served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, speaking on behalf of presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes.[81] Hayes won the nomination and, eventually, the presidency. In May 1877, President Hayes, an admirer of The Biglow Papers, sent William Dean Howells to Lowell with a handwritten note offering Lowell an ambassadorship to either Austria or Russia; Lowell declined, but noted his interest in Spanish literature.[82] Lowell was then offered and accepted the role of minister to the court of Spain at an annual salary of $12,000.[82] Lowell sailed from Boston on July 14, 1877, and, though he expected he would be away for a year or two, he would not return to the United States until 1885, with the violinist Ole Bull renting Elmwood for a portion of that time.[83] The Spanish media referred to him as "José Bighlow".[84] Lowell was well-prepared for his political role, having been trained in law, as well being able to read in multiple languages. He had trouble socializing while in Spain, however, and amused himself by sending humorous dispatches to his political bosses in the United States, many of which were later collected and published posthumously in 1899 as Impressions of Spain.[85]

In January 1880, Lowell was informed he was appointed Minister to England, his nomination made without his knowledge as far back as June 1879. He was granted a salary of $17,500 with about $3,500 for expenses.[86] While serving in this capacity, he addressed an importation of allegedly diseased cattle and made recommendations that predated the Pure Food and Drug Act.[87] As Queen Victoria commented, she had never seen an ambassador who "created so much interest and won so much regard as Mr. Lowell".[88] Lowell held this role until the close of Chester A. Arthur's presidency in the spring of 1885, despite his wife's failing health. Lowell was already well known in England for his writing and, during his time in England, he befriended fellow author Henry James, who referred to him as "conspicuously American".[88] Lowell also befriended Leslie Stephen during this time and became the godfather to his daughter, future writer Virginia Woolf.[89] Lowell was popular enough that he was offered a professorship at Oxford after his recall by president Grover Cleveland, though the offer was declined.[90]

Later years and death

He returned to the United States by June 1885, living with his daughter and her husband in Southboro, Massachusetts.[91] He then spent time in Boston with his sister before returning to Elmwood in November 1889.[92] By this time, most of his friends were dead, including Quincy, Longfellow, Dana, and Emerson, leaving him depressed and contemplating suicide again.[93] His second wife Frances had died on February 19, 1885, while still in England.[94] Lowell spent part of the 1880s delivering various speeches[95] and his last published works were mostly collections of essays, including Political Essays, and a collection of his poems Heartsease and Rue in 1888.[92] His last few years he traveled back to England periodically[96] and when he returned to the United States in the fall of 1889, he moved back to Elmwood[97] with Mabel, while her husband worked for clients in New York in New Jersey.[98] That year, Lowell also gave an address at the centenary of George Washington's inauguration. Also that year, the Boston Critic dedicated a special issue on his seventieth birthday to recollections and reminiscences by his friends, including former presidents Hayes and Benjamin Harrison and British Prime Minister William Gladstone as well as Alfred Tennyson and Francis Parkman.[97]

In the last few months of his life, Lowell struggled with gout, sciatica in his left leg, and chronic nausea; by the summer of 1891, doctors believed that Lowell had cancer in his kidneys, liver, and lungs. His last few months, he was administered opium for the pain and was rarely fully conscious.[99] He died on August 12, 1891, at Elmwood[100] and, after services in the Harvard chapel, was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery.[101] After his death, Norton served as his literary executor and published several collections of Lowell's works and his letters.[102]

Writing style and literary theory

Early in his career, James Russell Lowell's writing was influenced by Swedenborgianism, causing Frances Longfellow (wife of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) to mention that "he has been long in the habit of seeing spirits".[103] He composed his poetry rapidly when inspired by an "inner light" but could not write to order.[104] He subscribed to the common nineteenth-century belief that the poet was a prophet but went further, linking religion, nature, and poetry, as well as social reform.[103] Evert Augustus Duyckinck and others welcomed Lowell as part of Young America, a New York-based movement. Though not officially affiliated with them, he shared some of their ideals, including the belief that writers have an inherent insight into the moral nature of humanity and have an obligation for literary action in addition to their aesthetic function.[105] Unlike many of his contemporaries, including members of Young America, Lowell did not advocate for the creation of a new national literature. Instead, he called for a natural literature, regardless of country, caste, or race, and warned against provincialism which might "put farther off the hope of one great brotherhood".[26] He agreed with his neighbor Longfellow that "whoever is most universal, is also most national".[105] As Lowell said:

I believe that no poet in this age can write much that is good unless he gives himself up to [the radical] tendency... The proof of poetry is, in my mind, that it reduces to the essence of a single line the vague philosophy which is floating in all men's minds, and so render it portable and useful, and ready to the hand... At least, no poem ever makes me respect is author which does not in some way convey a truth of philosophy.[106]

A scholar of linguistics, Lowell was one of the founders of the American Dialect Society.[107] He used this interest in his writing, particularly in The Biglow Papers, presenting a heavily ungrammatical phonetic spelling of the Yankee dialect.[23] In using this vernacular, Lowell intended to get closer to the common man's experience and was rebelling against more formal and, as he thought, unnatural representations of Americans in literature. As he wrote in his introduction to The Biglow Papers, "few American writers or speakers wield their native language with the directness, precision, and force that are common as the day in the mother country".[108] Though intentionally humorous, this accurate presentation of the dialect was pioneering work in American literature.[109] For example, Lowell's character Hosea Biglow says in verse:

Ef you take a sword an' dror it,

An go stick a feller thru,

Guv'ment aint to answer to it,

God'll send the bill to you.[110]

Lowell is considered one of the Fireside Poets, a group of writers from New England in the 1840s who all had a substantial national following and their work was often read aloud by the family fireplace. Besides Lowell, the main figures from this group were Longfellow, Holmes, John Greenleaf Whittier, and William Cullen Bryant.[111]

Beliefs

Although he was an abolitionist, Lowell's opinions on African-Americans wavered. Though Lowell advocated suffrage for blacks, he noted that their ability to vote could be troublesome. Even so, he wrote, "We believe the white race, by their intellectual and traditional superiority, will retain sufficient ascendancy to prevent any serious mischief from the new order of things".[112] Freed slaves, he wrote, were "dirty, lazy & lying".[113] Even before his marriage to the abolitionist Maria White, Lowell wrote: "The abolitionists are the only ones with whom I sympathize of the present extant parties."[114] After his marriage, Lowell at first did not share White's enthusiasm for the cause but was eventually pulled in.[115] The couple often gave money to fugitive slaves, even when their own financial situation was not strong, especially if they were asked to free a spouse or child.[116] Even so, he did not always fully agree with the followers of the movement. The majority of these people, he said, "treat ideas as ignorant persons do cherries. They think them unwholesome unless they are swallowed, stones and all."[24] Lowell depicted Southerners very unfavorably in his second collection of The Biglow Papers but, by 1865, admitted that Southerners were "guilty only of weakness" and, by 1868, said that he sympathized with Southerners and their viewpoint on slavery.[117] Enemies and friends of Lowell alike questioned Lowell's vacillating interest in the question of slavery. Abolitionist Samuel Joseph May accused Lowell of trying to quit the movement because of his association with Harvard and the Boston Brahmin culture: "Having got into the smooth, dignified, self-complacent, and change-hating society of the college and its Boston circles, Lowell has gone over to the world, and to 'respectability'."[118]

Lowell was also involved in other reform movements. He urged for better conditions for factory workings, opposed capital punishment, and supported the temperance movement. His friend Longfellow was especially concerned about Lowell's fanaticism for temperance, worrying that Lowell would ask him to destroy his wine cellar.[20] There are many references to Lowell's drinking during his college years and part of his reputation in school was based on it. His friend Edward Everett Hale denied these allegations and, even then, Lowell considered joining the "Anti-Wine" club and later became a teetotaler during the early years of his first marriage.[119] However, as Lowell gained notoriety, he also was popular in social circles and clubs and, away from his wife, he would drink rather heavily. When he drank, he had wild mood swings, ranging from euphoria to frenzy.[120]

Criticism and legacy

In 1849, Lowell said of himself, "I am the first poet who has endeavored to express the American Idea, and I shall be popular by and by".[121] Poet Walt Whitman said: "Lowell was not a grower—he was a builder. He built poems: he didn't put in the seed, and water the seed, and send down his sun—letting the rest take care of itself: he measured his poems—kept them within formula."[122] Fellow Fireside Poet John Greenleaf Whittier praised Lowell, writing two poems in his honor, and calling him "our new Theocritus" and "one of the strongest and manliest of our writers–a republican poet who dares to speak brave words of unpopular truth".[123] British author Thomas Hughes referred to Lowell as one of the most important writers in the United States: "Greece had her Aristophanes; Rome her Juvenal; Spain has had her Cervantes; France her Rabelais, her Molière, her Voltaire; Germany her Jean Paul, her Heine; England her Swift, her Thackeray; and America has her Lowell."[111] Lowell's satires and use of dialect were an inspiration for writers like Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, H. L. Mencken, and Ring Lardner.[124]

Contemporary critic and editor Margaret Fuller wrote, "his verse is stereotyped; his thought sounds no depth, and posterity will not remember him".[125] Ralph Waldo Emerson noted that, though Lowell had significant technical skill, his poetry "rather expresses his wish, his ambition, than the uncontrollable interior impulse which is the authentic mark of a new poem... and which is felt in the pervading tone, rather than in brilliant parts or lines".[126] Even his friend Richard Henry Dana, Jr. questioned Lowell's abilities, calling him "very clever, entertaining & good humored... but he is rather a trifler, after all."[127] In the twentieth century, poet Richard Armour, questioned Lowell's ability, writing: "As a Harvard graduate and an editor for the Atlantic Monthly, it must have been difficult for Lowell to write like an illiterate oaf, but he succeeded."[128] The poet Amy Lowell featured her ancestor James Russell Lowell in her poem A Critical Fable (1922), the title mocking A Fable for Critics. Here, a fictional version of Lowell says he does not believe that women will ever be equal to men in the arts and "the two sexes cannot be ranked counterparts".[129] Modern literary critic Van Wyck Brooks wrote that Lowell's poetry was forgettable: "one read them five times over and still forgot them, as if this excellent verse had been written in water".[126]

Selected list of works

Poetry collections

- A Year's Life (1841)

- Miscellaneous Poems (1843)

- The Biglow Papers (1848)[37]

- A Fable for Critics (1848)[37]

- Poems (1848)[37]

- The Vision of Sir Launfal (1848)[37]

- Under the Willows (1868)[130]

- The Cathedral (1870)[130]

- Heartsease and Rue (1888)[92]

Essay collections

- Conversations on the Old Poets (1844)

- Fireside Travels (1864)[130]

- Among My Books (1870)[130]

- My Study Window (1871)[130]

- Among My Books (second collection, 1876)[130]

- Democracy and Other Addresses (1886)[92]

- Political Essays (1888)[92]

Further reading

- Greenslet, Ferris. James Russell Lowell, His Life and Work. Boston: 1905.

- Hale, Edward Everett. James Russell Lowell and His Friends. Boston: 1899.

- Scudder, Horace Elisha. James Russell Lowell: A Biography. Volume 1, Volume 2. Published 1901.

Notes

- ^ Sullivan, 204

- ^ Nelson, 39

- ^ a b Sullivan, 205

- ^ Heymann, 55

- ^ Wagenknecht, 11

- ^ Duberman, 14–15

- ^ a b Duberman, 17

- ^ a b Sullivan, 208

- ^ Duberman, 20

- ^ a b Duberman, 26

- ^ Sullivan, 209

- ^ Wagenknecht, 50

- ^ Wagenknecht, 135

- ^ a b c Sullivan, 210

- ^ Wagenknecht, 136

- ^ Heymann, 73

- ^ a b c Sullivan, 211

- ^ Yellin, Jean Fagan. "Hawthorne and the Slavery Question", A Historical Guide to Nathaniel Hawthorne, Larry J. Reynolds, ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001: 45. ISBN 0195124146

- ^ Duberman, 71

- ^ a b c Sullivan, 212

- ^ Wagenknecht, 16

- ^ Heymann, 72

- ^ a b c d Sullivan, 213

- ^ a b Heymann, 77

- ^ Hubbell, Jay B. The South in American Literature: 1607-1900. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1954: 373–374.

- ^ a b Duberman, 47

- ^ a b Duberman, 53

- ^ a b Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991: 201. ISBN 0060923318

- ^ Duberman, 410

- ^ Heymann, 76

- ^ Duberman, 113

- ^ a b Duberman, 101

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001: 141–142. ISBN 081604161X.

- ^ Nelson, 19

- ^ Duberman, 112

- ^ Heymann, 85

- ^ a b c d e Wagenknecht, 16

- ^ Duberman, 116

- ^ Duberman, 117

- ^ Wagenknecht, 36

- ^ Heymann, 98

- ^ a b Duberman, 139

- ^ Duberman, 134

- ^ Wagenknecht, 139

- ^ Heymann, 101

- ^ Duberman, 136

- ^ Heymann, 101–102

- ^ Duberman, 138

- ^ Heymann, 102

- ^ a b Duberman, 133

- ^ Heymann, 103

- ^ a b Duberman, 140

- ^ Heymann, 104–105

- ^ a b c Sullivan, 215

- ^ Duberman, 141

- ^ a b Heymann, 105

- ^ a b Sullivan, 216

- ^ a b Wagenknecht, 74

- ^ Heymann, 107

- ^ Duberman, 161

- ^ Heymann, 106

- ^ Duberman, 155

- ^ Duberman, 154

- ^ Duberman, 154–155

- ^ Heymann, 108

- ^ a b c Heymann, 119

- ^ Duberman, 180

- ^ a b Sullivan, 218

- ^ a b Heymann, 132

- ^ Wagenknecht, 183

- ^ Wagenknecht, 186

- ^ Heymann, 121

- ^ Duberman, 224

- ^ a b Heymann, 123

- ^ Wilson, 201

- ^ Duberman, 224–225

- ^ Baker, Thomas N. Nathaniel Parker Willis and the Trials of Literary Fame. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001: 187. ISBN 0-19-512073-6

- ^ Duberman, 243

- ^ a b Heymann, 134

- ^ Duberman, 258

- ^ Heymann, 136

- ^ a b Duberman, 282

- ^ Duberman, 282–283

- ^ Heymann, 137

- ^ Heymann, 136–138

- ^ Duberman, 298–299

- ^ Wagenknecht, 168

- ^ a b Sullivan, 219

- ^ Duberman, 447

- ^ Sullivan, 218–219

- ^ Heymann, 145

- ^ a b c d e Wagenknecht, 18

- ^ Dubermann, 339

- ^ Heymann, 143

- ^ Duberman, 352

- ^ Duberman, 351

- ^ a b Heymann, 150

- ^ Duberman, 364–365

- ^ Duberman, 370

- ^ Duberman, 371

- ^ Sullivan, 223

- ^ Heymann, 152

- ^ a b Duberman, 62

- ^ Wagenknecht, 105–106

- ^ a b Duberman, 50

- ^ Duberman, 50–51

- ^ Wagenknecht, 70

- ^ Heymann, 86

- ^ Wagenknecht, 71

- ^ Heymann, 87

- ^ a b Heymann, 91

- ^ Wagenknecht, 175

- ^ Duberman, 229

- ^ Heymann, 63

- ^ Heymann, 64

- ^ Duberman, 112–113

- ^ Wagenknecht, 187

- ^ Heymann, 122

- ^ Wagenknecht, 29

- ^ Heymann, 117

- ^ Sullivan, 203

- ^ Nelson, 171

- ^ Wagenknecht, Edward. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Portrait in Paradox. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967: 113.

- ^ Heymann, 90

- ^ Blanchard, Paula. Margaret Fuller: From Transcendentalism to Revolution. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1987: 294. ISBN 0-201-10458-X

- ^ a b Sullivan, 220

- ^ Sullivan, 219–220

- ^ Nelson, 146

- ^ Watts, Emily Stipes. The Poetry of American Women from 1632 to 1945. Austin, Texas: University of Austin Press, 1978: 159–160. ISBN 0-292-76540-2

- ^ a b c d e f Wagenknecht, 17

Sources

- Duberman, Martin. James Russell Lowell. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1966.

- Heymann, C. David. American Aristocracy: The Lives and Times of James Russell, Amy, and Robert Lowell. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1980. ISBN 0396076084

- Nelson, Randy F. The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981. ISBN 086576008X

- Sullivan, Wilson. New England Men of Letters. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1972. ISBN 0027886808

- Wagenknecht, Edward. James Russell Lowell: Portrait of a Many-Sided Man. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

External links

- Works by James Russell Lowell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by James Russell Lowell at Internet Archive

- Full View Books with PDF downloads at Google Books

- The Complete Writings of James Russell Lowell, edited by Charles Eliot Norton

- American poets

- American essayists

- American satirists

- American abolitionists

- United States ambassadors to the United Kingdom

- United States ambassadors to Spain

- Atlantic Monthly people

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Harvard University alumni

- People from Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Scottish-Americans

- 1819 births

- 1891 deaths