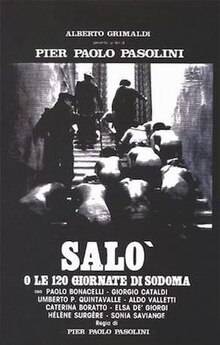

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom

| Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Pier Paolo Pasolini |

| Written by | Pier Paolo Pasolini Sergio Citti |

| Produced by | Alberto Grimaldi Alberton De Stefanis Antonio Girasante |

| Starring | Paolo Bonacelli Giorgio Cataldi Umberto Paolo Quintavalle Caterina Boratto Elsa De Giorgi Hélène Surgère Sonia Saviange Renata Moar Franco Merli Inès Pellegrini |

| Cinematography | Tonino Delli Colli |

| Edited by | Nino Bragli Tatiana Casini Morigi Enzo Ocone |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | 30 January 1976 |

Running time | 116 min. |

| Language | Italian |

Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom) is a controversial 1975 film written and directed by Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini with uncredited writing contributions by Pupi Avati.[1][2] It is based on the book The 120 Days of Sodom by the Marquis de Sade.

Because of its scenes of intensely sadistic graphic violence, the movie was extremely controversial upon its release, and remains banned in several countries to this day. It was Pasolini's last film; he was murdered shortly before Salò was released.

Plot

Salò (the film's common abbreviation) occurs in the Republic of Salò, the Fascist rump state established in the Nazi-occupied portion of Italy in 1944. The story is in four segments loosely parallel to Dante's Inferno: the Anteinferno, the Circle of Manias, the Circle of Feces, and the Circle of Blood.

Four men of power, the Duke (Duc de Blangis), the Bishop, the Magistrate (Curval), and the President agree to marry each other's daughters as the first step in a debauched ritual. With the aid of several collaborator young men, they kidnap eighteen young men and women (nine of each sex), and take them to a palace near Marzabotto. Accompanying them are four middle-aged prostitutes, also collaborators, whose function in the debauchery will be to recount erotically arousing stories for the men of power, and who, in turn, will sadistically exploit their victims.

The story depicts the many days at the palace, during which the four men of power devise increasingly abhorrent tortures and humiliations for their own pleasure. A most infamous scene, shows a young woman forced to eat the feces of the Duke; later, the other victims are presented a giant meal of human feces. At story's end, the victims who chose to not collaborate with their fascist tormentors are gruesomely murdered: scalping, branding, tongue and eyes cut out; (see Franco Merli). The viewer is distanced from the grossest tortures, because they are viewed through binoculars. The story's final scene — two young, macho soldiers dancing a waltz, together — embodies Pasolini's vision of life and death: unflinching, dispassionate, yet, humane and (paradoxically) impassioned.

Production

Salò transposes the setting of Sade's book from 18th century France to the last days of Mussolini's regime in the Republic of Salò. However, despite the horrors that it shows (rape, torture, and mutilation), it barely touches the perversions listed in the book, which include extensive sexual and physical abuse of children.

While the book provides the most important foundations of Salò, the events in the film draw as much on Pasolini's own life as on Sade's novel. Pasolini spent part of his early twenties in the Republic of Salò. During this time he witnessed a great many cruelties on the part of the Fascist collaborationist forces of the Salò Republic. Pasolini’s life followed a strange course of early experimentation and constant struggle. Growing up in Bologna and Friuli, Pasolini was introduced to many leftist examples in mass culture from an early age. He began writing at age seven, heavily under the influence of French poet Arthur Rimbaud. His writing quickly began to incorporate certain aspects of his personal life, mainly dealing with constant familial struggles and moving from city to city.

After studying major literary giants in high school, Pasolini enrolled in the University of Bologna for further education. Many of his memories of the experience led to the conceptualization of Salò. He also claimed that the film was highly symbolic and metaphorical; for instance, that the coprophagia scenes were an indictment of mass-produced foods, which he labeled "useless refuse."

Although his career, in both film and literature, was highly prolific and far-reaching, Pasolini dealt with some major constants within his work. His first published novel in 1955 dealt with the concept of pimps and scandals within a world of prostitution. The reception of this first novel, titled Ragazzi di vita, created much scandal and brought about subsequent charges of obscenity.

One of his first major films, Accattone (1961), dealt with similar issues and was also received by an unwelcoming audience, who demanded harsher codes of censorship. It is hard to quickly sum up the vast amount of work which Pasolini created throughout his lifetime, but it becomes clear that so much of it focused around a very personal attachment to subject matter, as well as overt sexual undertones.

Film's treatment of sexuality

A persistent theme in Salò is the degradation and modification of the human body. Throughout the story, the human body is reduced to something of lesser value than a person — for example, never does a sexual encounter occur in private. Salò has been referred to as a film presenting the "death of sex", a "funeral dirge" of eroticism amidst of sex's mass commercialization.[3] Although men and women are naked throughout the story, sexual intercourse mostly is presented as an act of degradation. Thus, one of the libertines makes love to a guard, then goes to inspect the captive teenagers. When he finds two women making love (in violation of the libertines' laws), they reveal that another guard has been sleeping with a maid. The libertines then seek and kill the guard and the maid. Salò's depiction of sexual intercourse contrasts with that in pornography and erotic cinema: Pornography presents sexual intercourse as lusty and joyful, using foreplay to mark sexual acts as passionate and exciting. Salò presents sexual intercourse as pain, and deliberately avoids cinematic foreplay, leaving the sex acts as devoid of romantic allure and intrigue. Sexual relations may also be described as pointless; they are certainly not pleasurable.

Reception

Controversy

To date, Salò remains controversial, with many praising the film's fearlessness and willingness to contemplate the unthinkable, while others roundly condemn it for being little more than a pretentious exploitation movie. Salò has been banned in several countries, because of its graphic portrayals of rape, torture and murder — mainly of people thought to be younger than eighteen years of age. The fact that Salò is set in a Fascist period makes many of the sadomasochistic aspects of the film more difficult to bear than in de Sade's original novel. The setting and the emphasis upon perverse consumption connects the brutality of Fascism to what Pasolini saw as the brutalizing effects of the modification of sexuality under late capitalism.

Salò was banned in Australia in 1976, then made briefly legal in 1993 until its re-banning in 1998.[4][5] In 1994, an undercover policeman, in Cincinnati, Ohio, rented the film from a local gay bookstore, and then arrested the owners for "pandering". A large group of artists, including Martin Scorsese and Alec Baldwin, and scholars signed a legal brief arguing the film's artistic merit; the case was dismissed on a technicality.[6] For a time, Salò was unavailable in many countries; it is now available, uncut, on DVD in the United Kingdom, France, Finland, Greece, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Italy, Austria, and Germany; however, in Sweden, the film was never banned or cut. Salò was resubmitted for classification in Australia in 2008, only to be rejected once again[7]. The DVD print was apparently a modified version, causing outrage in the media over censorship and freedom of speech.

Documentaries about the film

An exhibition of photographs by Fabian Cevallos depicting scenes which were edited out of the film was displayed in 2005 in Rome. Italian filmmaker Giuseppe Bertolucci released a documentary in 2006, Pasolini prossimo nostro, based on an interview with Pasolini done on the set of Salò in 1975. The documentary also includes photographs taken on the set of the film. The film is also the subject of a 2001 documentary written and directed by Mark Kermode.

Acclaim

The film is regarded a masterpiece in some quarters. Acclaimed director Michael Haneke named the film one of his ten favorite films when he voted for the 2002 Sight and Sound poll, director Catherine Breillat and film critic Joel David also voted for the film.[8] In a 2000 poll of critics conducted by the The Village Voice named it the 89th greatest film of the 20th century.[9]. In 2006, the Chicago Film Critics Association named Salo the 65th scariest film ever made.[10]

Versions

Several versions of the film exist, Salò originally ran 145 minutes, but director Pasolini himself removed 25 minutes for story pace. The longest available version is the DVD published by the BFI, containing a short scene usually deleted from other prints, in which during the first wedding one of the masters quotes a Gottfried Benn poem. This version of the film is featured both on the original 2001 DVD release and the remastered 2008 DVD and Blu-ray. Since the remastered version was sourced from the original negative, which does not include the poetry reading, the additional footage was sourced from a 35mm print of the film held by the BFI National Archive. A note in the DVD booklet explains that this leads to a slight shift in picture quality. Aside from the high-definition transfer, the 2008 BFI releases are identical - the apparent five-minute difference in running time is explained by the Blu-ray running at the theatrical speed of 24 frames per second, while the DVD has been transferred at the slightly faster PAL video rate of 25 frames per second.

In the U.S., Salò suffers intermittent legal troubles. Criterion Collection laserdisc and DVD editions were released for North America; however, the DVD was quickly withdrawn because of licensing conflicts with Pasolini's estate. As a resultant, Criterion's 1998 DVD release of the film created much collector's interest, because of its rarity — dubbed "The Rarest DVD in the world", whilst many discontinued Criterion titles are much sought, Salò original DVDs command prices ranging from $250 to $1,000 American dollars. Moreover, its rarity inspired bootleg copies sold as original pressings. The quality of the genuine Salò DVD is inferior, by contemporary standards; most notably, the image has a green tinge.

Besides the BFI edition with the often missing poetry-quotation scene (and better than Criterion's edition), there exists a French DVD version, distributed by Gaumont Columbia Tristar Home Video, containing a transfer that is a restored, high-definition, color-corrected version of the film (superior to the Criterion and BFI editions), however, it has no English subtitles, as it is a French product for French cinemaphiles.

The Hawaii film company HK Flix released an NTSC-format Salò through distributor Euro Cult in 2007. It reportedly contains the uncut Criterion Collection release — yet of better quality. The HK Flix edition is an NTSC version of the BFI's Salò DVD, complete with a factory imperfection at the film's 01:47:19 mark, however, its quality is unequal to that of the Gaumont DVD, and, still, it is missing a scene. The DVD cover is a sketch of Pasolini in sunglasses; Paolo Bonacelli's name is printed beside it. Moreover, despite accusations of boot-legging, Euro Cult assert their legal entitlement to distribute the Salò DVD in the U.S.

In its on-line blog, On Five, the Criterion company said, in November 2006, that they re-acquired the distribution rights for Salò. In May 2008, Criterion released the cover art of the reissue DVD, slated for release in August 2008, comprising two discs: (i) the film (with an optional dubbed-English track) and (ii) three documentaries and new interviews.[11]

In August 2008, the BFI announced a new release of Salò on both high-definition Blu-ray and standard-definition DVD, claiming it to be "fully uncut and in its most complete version", and that "the film has been re-mastered from the original Italian restoration negatives" and would be accompanied by a second disc containing extensive additional features.[12] The BFI re-issue does indeed contain the missing 25 second poem intact. The films transfer differs from the Criterion release as colours are more subtle without contrast boosting, like the Criterion reissue.

References

- ^ http://cinebeats.blogsome.com/category/pupi-avati/

- ^ http://www.dvdtalk.com/dvdsavant/s765house.html

- ^ Musatti 1982, 131; Chaper 1975-6, 116.

- ^ Salo is re-banned (in Australia), by Terry Lane, March 98

- ^ Salo - 120 Days of Sodom | Refused-Classification.com

- ^ ACLU Arts Censorship Project Newsletter

- ^ http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/news/national/sadistic-sex-movie-ban-attacks-art-expression/2008/07/19/1216163226456.html

- ^ http://www.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/topten/poll/voted.php?film=Sal%C3%B2%20(Pasolini)

- ^ http://www.filmsite.org/villvoice.html

- ^ http://www.filmspotting.net/top100.htm

- ^ CRITERION COLLECTION Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom DVD

- ^ BFI Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom Blu-ray and DVD

External links

- Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma at IMDb

- Criterion Collection essay on Salò, by John Powers

- Rare OOP DVDs Guide to identify original Criterion DVD.

- DVDBeaver.com Version Comparison Features, image, and sound quality comparison of the different DVD releases.

- Film on Pasolini to debut at Venice film festival