Maya numerals

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

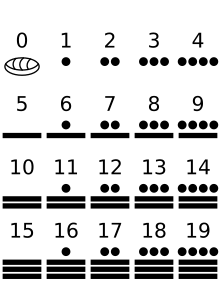

The Pre-Columbian Maya civilization used a vigesimal (base-twenty) numeral system.

The numerals are made up of three symbols; zero (shell shape), one (a dot) and five (a bar). For example, nineteen (19) is written as four dots in a horizontal row above three horizontal lines stacked upon each other.

Numbers above 19

| 400s | |||

| 20s | |||

| 1s | |||

| 33 | 429 | 5125 |

Numbers after 19 were written vertically up in powers of twenty. For example, thirty-three would be written as one dot above three dots, which are in turn atop two lines. The first dot represents "one twenty" or "1×20", which is added to three dots and two bars, or thirteen. Therefore, (1×20) + 13 = 33. Upon reaching 20^2 or 400, another row is started. The number 429 would be written as one dot above one dot above four dots and a bar, or (1×400) + (1×20) + 9 = 429. The powers of twenty are numerals, just as the Hindu-Arabic numeral system uses powers of tens.

[1]

Other than the bar and dot notation, Maya numerals can be illustrated by face type glyphs. The face glyph for a number represents the deity associated with the number. These face number glyphs were rarely used, and are mostly seen only on some of the most elaborate monumental carving.

Addition and Subtraction

Adding and subtracting numbers below 20 using Maya numerals is very simple. [1]

Addition is performed by combining the numeric symbols at each level:

![]()

If five or more dots result from the combination, five dots are removed and replaced by a bar. If four or more bars result, four bars are removed and a dot is added to the next higher column.

Similarly with subtraction, remove the elements of the subtrahend symbol from the minuend symbol:

![]()

If there are not enough dots in a minuend position, a bar is replaced by five dots. If there are not enough bars, a dot is removed from the next higher minuend symbol in the column and four bars are added to the minuend symbol being worked on.

Zero

The Maya/Mesoamerican Long Count calendar required the use of zero as a place-holder within its vigesimal positional numeral system. A shell glyph --![]() -- was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the earliest of which (on Stela 2 at Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas) has a date of 36 BCE.[2]

-- was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the earliest of which (on Stela 2 at Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas) has a date of 36 BCE.[2]

However, since the eight earliest Long Count dates appear outside the Maya homeland,[3] it is assumed that the use of zero predated the Maya, and was possibly the invention of the Olmec. Indeed, many of the earliest Long Count dates were found within the Olmec heartland. However, the Olmec civilization had come to an end by the 4th century BCE, several centuries before the earliest known Long Count dates--which suggests that zero was not an Olmec discovery.

In the calendar

In the "Long Count" portion of the Maya calendar, a variation on the strictly vigesimal numbering is used. The Long Count changes in the third place value; it is not 20×20 = 400, as would otherwise be expected, but 18×20, so that one dot over two zeros signifies 360. This is supposed to be because 360 is roughly the number of days in a year. (Some hypothesize that this was an early approximation to the number of days in the solar year, although the Maya had a quite accurate calculation of 365.2422 days for the solar year at least since the early Classic era[citation needed].) Subsequent place values return to base-twenty.

In fact, every known example of large numbers uses this 'modified vigesimal' system, with the third position representing multiples of 18×20. It is reasonable to assume, but not proven by any evidence, that the normal system in use was a pure base-20 system.

External links

- Maya Mathematics online converter from decimal numeration to Maya numeral notation.

- Anthropomorphic Maya numbers online story of number representations.

Notes

- ^ Saxakali (1997). "Maya Numerals". Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ No long count date actually using the number 0 has been found before the 3rd century CE, but since the long count system would make no sense without some placeholder, and since Mesoamerican glyphs do not typically leave empty spaces, these earlier dates are taken as indirect evidence that the concept of 0 already existed at the time.

- ^ Diehl (2004, p.186).

References

- Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya (4th edition (revised) ed.). London; New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Díaz Díaz, Ruy (2006). "Apuntes sobre la aritmética Maya" (online reproduction). Educere. 10 (35). Táchira, Venezuela: Universidad de los Andes: 621–627. ISSN 1316-4910. OCLC 66480251.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Template:Es icon - Diehl, Richard (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-02119-8. OCLC 56746987.

{{cite book}}: templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Thompson, J. Eric S. (1971). Maya Hieroglyphic Writing; An Introduction. Civilization of the American Indian Series, No. 56 (3rd edition ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-806-10447-3. OCLC 275252.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|author=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)