Monopoly

| Competition law |

|---|

|

| Basic concepts |

| Anti-competitive practices |

|

| Enforcement authorities and organizations |

Template:Two other uses In economics, a monopoly (from Greek monos , alone or single + polein , to sell) exists when a specific individual or enterprise has sufficient control over a particular product or service to determine significantly the terms on which other individuals shall have access to it.[1] Monopolies are thus characterized by a lack of economic competition for the good or service that they provide and a lack of viable substitute goods.[2] The verb "monopolize" refers to the process by which a firm gains persistently greater market share than what is expected under perfect competition.

A monopoly should be distinguished from monopsony, in which there is only one buyer of a product or service ; a monopoly may also have monopsony control of a sector of a market. Likewise, a monopoly should be distinguished from a cartel (a form of oligopoly), in which several providers act together to coordinate services, prices or sale of goods. Monopolies can form naturally or through vertical or horizontal mergers. A monopoly is said to be coercive when the monopoly firm actively prohibits competitors from entering the field.

In many jurisdictions, competition laws place specific restrictions on monopolies. Holding a dominant position or a monopoly in the market is not illegal in itself, however certain categories of behaviour can, when a business is dominant, be considered abusive and therefore be met with legal sanctions. A government-granted monopoly or legal monopoly, by contrast, is sanctioned by the state, often to provide an incentive to invest in a risky venture or enrich a domestic constituency. The government may also reserve the venture for itself, thus forming a government monopoly.

Economic analysis

|

In economics, the study of market structures under imperfect competition begins with the analysis of Monopoly. If there is a single seller in a certain industry and there are no close substitutes for the good being produced by her, then the market structure is that of a Pure monopoly. Sometimes, there are many sellers in an industry and/or there exist many close substitutes for the good being produced, but nevertheless firms retain some market power. This is called Monopolistic competition by economists, whereas Oligopoly refers to the case where the main theoretical framework revolves around firm's strategic interactions.

A company with a monopoly does not undergo price pressure from competitors, although it may face pricing pressure from potential competition. If a company raises prices too high, then others may enter the market if they are able to provide the same good, or a substitute, at a lower price.[3] The idea that monopolies in markets with easy entry need not be regulated against is known as the "revolution in monopoly theory".[4] [verification needed]

A monopolist can extract only one premium[clarification needed], and getting into complementary markets does not pay. That is, the total profits a monopolist could earn if it sought to leverage its monopoly in one market by monopolizing a complementary market are equal to the extra profits it could earn anyway by charging more for the monopoly product itself. However, the one monopoly profit theorem does not hold true if customers in the monopoly good are stranded or poorly informed, or if the tied good has high fixed costs.

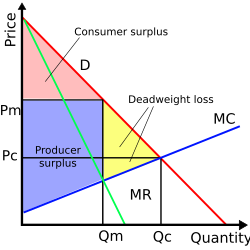

A pure monopoly follows the same economic rationality of firms under perfect competition, i.e. to optimize a profit function given some constraints. Under the assumptions of increasing marginal costs, exogenous inputs' prices, and control concentrated on a single agent or entrepeneur, the optimal decision is to equate the marginal cost and marginal revenue of production (see diagram). Nonetheless, a pure monopoly can -unlike a competitive firm- alter the market price for her own convenience: a decrease in the level of production results in a higher price. In the economics' jargon, it is said that pure monopolies "face a downward-sloping demand". An important consequence of such behaviour is worth noticing: typically a monopoly selects a higher price and lower quantity of output than a price-taking firm; again, less is available at a higher price.[5]

There are important points for one to remember when considering the monopoly model diagram (and its associated conclusions) displayed here. The result that monopoly prices are higher, and production output lower, than a competitive firm follow from a requirement that the monopoly not charge different prices for different customers. That is, the monopoly is restricted from engaging in price discrimination (this is called first degree price discrimination, where all customers are charged the same amount). If the monopoly were permitted to charge individualized prices (this is called third degree price discrimination), the quantity produced, and the price charged to the marginal customer, would be identical to a competitive firm, thus eliminating the deadweight loss; however, all gains from trade (social welfare) would accrue to the monopolist and none to the consumer. In essence, every consumer would be just indifferent between (1) going completely without the product or service and (2) being able to purchase it from the monopolist.

As long as the price elasticity of demand for most customers is less than one in absolute value, it is advantageous for a firm to increase its prices: it then receives more money for fewer goods. With a price increase, price elasticity tends to rise, and in the optimum case above it will be greater than one for most customers.

Monopoly and Efficiency

According to the standard model, in which a monopolist sets a single price for all consumers, the monopolist will sell a lower quantity of goods at a higher price than would firms under perfect competition. Because the monopolist ultimately forgoes transactions with consumers who value the product or service more than its cost, monopoly pricing creates a deadweight loss referring to potential gains that went neither to the monopolist or to consumers. Given the presence of this deadweight loss, the combined surplus (or wealth) for the monopolist and consumers is necessarily less than the total surplus obtained by consumers under perfect competition. Where efficiency is defined by the total gains from trade, the monopoly setting is less efficient than perfect competition.

It is often argued that monopolies tend to become less efficient and innovative over time, becoming "complacent giants", because they do not have to be efficient or innovative to compete in the marketplace. Sometimes this very loss of psychological efficiency can raise a potential competitor's value enough to overcome market entry barriers, or provide incentive for research and investment into new alternatives The theory of contestable markets argues that in some circumstances (private) monopolies are forced to behave as if there were competition because of the risk of losing their monopoly to new entrants. This is likely to happen where a market's barriers to entry are low. It might also be because of the availability in the longer term of substitutes in other markets. For example, a canal monopoly, while worth a great deal in the late eighteenth century United Kingdom,was worth much less in the late nineteenth century because of the introduction of railways as a substitute.

In the short run it can be good to allow a firm to attempt to monopolize a market, since practices such as Predatory pricing can benefit consumers. When monopolies are not broken through the open market, sometimes a government will step in, either to regulate the monopoly, turn it into a publicly owned monopoly environment, or forcibly break it up (see Antitrust law). Public utilities, often being naturally efficient with only one operator and therefor less susceptible to efficient breakup, are often strongly regulated or publicly owned. AT&T and Standard Oil are debatable examples of the breakup of a private monopoly. When AT&T was broken up into the "Baby Bell" components, MCI, Sprint, and other companies were able to compete effectively in the long distance phone market and began to take phone traffic from the less efficient AT&T server.

Law

The existence of a very high market share does not always mean consumers are paying excessive prices since the threat of new entrants to the market can restrain a high-market-share firm's price increases. Competition law does not make merely having a monopoly illegal, but rather abusing the power a monopoly may confer, for instance through exclusionary practices.

First it is necessary to determine whether a firm is dominant, or whether it behaves "to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, customers and ultimately of its consumer."[6] As with collusive conduct, market shares are determined with reference to the particular market in which the firm and product in question is sold.

Under EU law, very large market shares raises a presumption that a firm is dominant,[7] which may be rebuttable.[8] If a firm has a dominant position, then there is "a special responsibility not to allow its conduct to impair competition on the common market".[9] The lowest yet market share of a firm considered "dominant" in the EU was 39.7%.[10]

Certain categories of abusive conduct are usually prohibited under the country's legislation, though the lists are seldom closed.[11] The main recognized categories are:

- Predatory pricing

- Tying (commerce) and product bundling

- Limiting supply

- Price discrimination

- Refusal to deal and exclusive dealing

Despite wide agreement that the above constitute abusive practices, there is some debate about whether there needs to be a causal connection between the dominant position of a company and its actual abusive conduct. Furthermore, there has been some consideration of what happens when a firm merely attempts to abuse its dominant position.

Historical monopolies

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

The term "monopoly" first appears in Aristotle's Politics, wherein Aristotle describes Thales of Miletus' cornering of the market in olive presses as a monopoly[12] (μονοπωλίαν)[13].

Common salt (sodium chloride) historically gave rise to natural monopolies. Until recently, a combination of strong sunshine and low humidity or an extension of peat marshes was necessary for winning salt from the sea, the most plentiful source. Changing sea levels periodically caused salt "famines" and communities were forced to depend upon those who controlled the scarce inland mines and salt springs, which were often in hostile areas (the Dead Sea, the Sahara desert) requiring well-organized security for transport, storage, and distribution. The "Gabelle", a notoriously high tax levied upon salt, played a role in the start of the French Revolution, when strict legal controls were in place over who was allowed to sell and distribute salt.

Robin Gollan argues in The Coalminers of New South Wales that anti-competitive practices developed in the Newcastle coal industry as a result of the business cycle. The monopoly was generated by formal meetings of the local management of coal companies agreeing to fix a minimum price for sale at dock. This collusion was known as "The Vend." The Vend collapsed and was reformed repeatedly through-out the late nineteenth century, cracking under recession in the business cycle. "The Vend" was able to maintain its monopoly due to trade union support, and material advantages (primarily coal geography). In the early twentieth century as a result of comparable monopolistic practices in the Australian coastal shipping business, the vend took on a new form as an informal and illegal collusion between the steamship owners and the coal industry, eventually going to the High Court as Adelaide Steamship Co. Ltd v. R. & AG.[14]

Examples of alleged and legal monopolies

- The salt commission, a legal monopoly in China formed in 758.

- British East India Company; created as a legal trading monopoly in 1600.

- Standard Oil; broken up in 1911, two of its surviving "baby companies" are ExxonMobil and Chevron.

- Major League Baseball; survived U.S. anti-trust litigation in 1922, though its special status is still in dispute as of 2009.

- Microsoft; settled anti-trust litigation in the U.S. in 2001; fined by the European Commission in 2004 for 497 million Euros [1], which was upheld for the most part by the Court of First Instance of the European Communities in 2007. The fine was 1.35 Billion USD in 2008 for noncompliance with the 2004 rule.[15][16]

- Joint Commission; has a monopoly over whether or not US hospitals are able to participate in the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

See also

- Monopolistic competition

- Complementary monopoly

- Duopoly

- Monopsony

- Bilateral monopoly

- Oligopoly

- Ramsey problem, a policy rule concerning what price a monopolist should set

Notes and references

- ^ Milton Friedman (2002). "VIII: Monopoly and the Social Responsibility of Business and Labor". Capitalism and Freedom (40th anniversary edition ed.). The University of Chicago Press. p. 208. ISBN 0-226-26421-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|format=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonth=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Blinder, Alan S (2001). "11: Monopoly". Microeconomics: Principles and Policy. Thomson South-Western. p. 212. ISBN 0-324-22115-0.

A pure monopoly is an industry in which there is only one supplier of a product for which there are no close substitutes and in which is very difficult or impossible for another firm to coexist

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonth=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Depken, Craig (November 23, 2005). "10". Microeconomics Demystified. McGraw Hill. p. 170. ISBN 0071459111.

- ^ The revolution in monopoly theory, by Glyn Davies and John Davies. Lloyds Bank Review, July 1984, no. 153, p. 38-52.

- ^ Levine, David (2008-09-07). Against intellectual monopoly. Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0521879286.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ C-27/76 United Brands Continental BV v. Commission [1978] ECR 207

- ^ C-85/76 Hoffmann-La Roche & Co AG v. Commission [1979] ECR 461

- ^ AKZO [1991]

- ^ Michelin [1983]

- ^ BA/Virgin [2000] OJ L30/1

- ^ Continental Can [1973]

- ^ Aristotle: Politics: Book 1

- ^ Aristotle, Politics

- ^ Robin Gollan, The Coalminers of New South Wales: a history of the union, 1860-1960, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1963, 45-134.

- ^ Leo Cendrowicz. "Microsoft Gets Mother Of All EU Fines". Forbes. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|datepublished=ignored (help) - ^ "EU fines Microsoft record $1.3 billion". Time Warner. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|datepublished=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Guy Ankerl, Beyond Monopoly Capitalism and Monopoly Socialism. Cambridge,Mass.: Schenkman Pbl., 1978. ISBN0870739387

- Impact of Antitrust Laws on American Professional Team Sports

External links

- Monopoly: A Brief Introduction by The Linux Information Project

- Monopoly by Elmer G. Wiens: Online Interactive Models of Monopoly (Public or Private) and Oligopoly

- Monopoly Profit and Loss by Fiona Maclachlan and Monopoly and Natural Monopoly by Seth J. Chandler, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

Criticism

- Natural Monopoly and Its Regulation

- The Myth of the Natural Monopoly

- Natural Monopoly and Its Regulation

- From rulers' monopolies to users' choices A critical survey of monopolistic practices

- Body of Knowledge on Infrastructure Regulation Monopoly and Market Power