David and Jonathan

- David and Jonathan is also the name adopted by recording duo Roger Cook and Roger Greenaway.

- David et Jonathan is also a French duo.

David (Hebrew: דָּוִ(י)ד Dāwīḏ or David) and Jonathan (Hebrew: יְהֹונָתָן Yəhōnāṯān or Yehonatan) were heroic figures of the Kingdom of Israel, whose intimate relationship was recorded favourably in the Old Testament books of Samuel.

These texts record the close relationship between the two. A solemn compact is made before the enmity of King Saul leads David to flee and hide. Despite Jonathan's attempts to intercede with his father, David is finally forced to leave. When David takes his tender farewell of Jonathan the men kiss each other as they shed tears.

The traditional and mainstream religious interpretation of the relationship has been one of platonic love and an example of homosociality. Some later Medieval and Renaissance literature drew upon the story to underline strong personal friendships between men, some of which involved romantic love. Jonathan loved (ahab) David as himself (kenapso), and this love, which David calls more wonderful than the love of women, is expressed also physically.

In modern times, some scholars, writers, as well as activists have emphasizsed what they believe to be elements of homoeroticism (chaste or otherwise) in the story in order to support a sympathetic reading within the Bible of same-sex orientation.

Story of David and Jonathan

The relationship between David and Jonathan is mainly covered in the Old Testament First Book of Samuel, although elements are to be found also in the Second Book. The episodes belong to the story of David's ascent to power, which is commonly regarded as one of the sources of the Deuteronomistic history, and to its later additions.

David the handsome, ruddy-cheeked youth and the youngest son of Jesse, is brought before Saul, the first king of Israel, having slain the giant Philistine warrior Goliath. Jonathan, the eldest son of Saul, is immediately struck by this first encounter:

"That same day, when Saul had finished speaking with David, he kept him and would not let him return any more to his father's house, for he saw that Jonathan had given his heart to David and had grown to love him as himself. So Jonathan and David made a solemn compact because they loved the other as dearly as himself. And Jonathan stripped off the cloak he was wearing and his tunic, and gave them to David, together with his sword, his bow, and his belt."[1]

Saul's anger

The Israelite people are quick to accept David amongst them. However, this provokes the ire and jealousy of Saul, who makes several failed attempts to kill David. Learning of one of these attempts, Jonathan warns David to hide because he "took great delight in David."[2] David eventually flees; but still seeks solace with Jonathan while alleging that Saul knows about the friendship and therefore keeps his real intentions or undertakings hidden from his son, "Your father knows well that you like me."[3]

The two connive to find out more about Saul's intentions and swear to each other eternal friendship, which would encompass both families. So "Jonathan pledged himself afresh to David because of his love for him, and he loved him as himself".[4]

David hides

David agrees to hide until Jonathan can confront his father and ascertain whether it is safe for David to stay. Jonathan approaches Saul to plead David's cause: "Then Saul's anger was kindled against Jonathan. He said to him, 'You son of a perverse, rebellious woman! Do I not know that you have chosen the son of Jesse to your own shame, and to the shame of your mother's nakedness?'"[5]

Jonathan is so grieved that he does not eat for days. He goes to David at his hiding place to tell him that it is unsafe for him and he must leave, and the episode ends with a heartbreaking farewell.

"...David rose from beside the stone heap and prostrated himself with his face to the ground. He bowed three times, and they kissed each other, and wept with each other; David wept the more. Then Jonathan said to David, 'Go in peace, since both of us have sworn in the name of the LORD, saying, "The LORD shall be between me and you, and between my descendants and your descendants, for ever."' He got up and left and Jonathan went into the city."<ref>1 Sam. 20:41–42</ref>

The death of Jonathan

As Saul continues to pursue David, the pair renew their covenant, after which they do not meet again. Eventually Saul and David reconcile. When Jonathan is slain on Mt Gilboa by the Philistines along with his father, David laments his death saying:

"I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan; greatly beloved were you to me; your love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women."[6]

Traditional interpretation

A platonic interpretation for the relationship between David and Jonathan has been the mainstream view found in biblical exegesis, as led by Jewish and Christian writers. This argues that the relationship between the two, although strong and close, is ultimately a platonic friendship. The covenant that is made is political, and not erotic; while any intimacy is a case of male bonding and homosociality.

David and Jonathan's love is understood as the intimate camaraderie between two young soldiers with no sexual involvement. The books of Samuel do not actually document physical intimacy between the two characters. Nothing indicates that David and Jonathan slept together. Neither of the men are described as having problems in their heterosexual married life. David had an abundance of wives and concubines as well as an adulterous affair with Bathsheba, and suffered impotence only as an old man, while Jonathan had a five year-old son at his death.[7]

The story was being told after the Holiness Code had been put into practice, with its commands and prohibitions of sexual contact between males which regulated the Israelites' sexual morality. Some traditionalists who subscribe to the Documentary Hypothesis, note the significance of the lack of censoring of the descriptions at issue, in spite of the Levitical injunctions against homoerotic contact. Gagnon notes, "The narrator’s willingness to speak of David’s vigorous heterosexual life (compare the relationship with Bathsheba) puts in stark relief his (their) complete silence about any sexual activity between David and Jonathan."[8]

Presuming such editing would have taken place, Martti Nissinen comments, "Their mutual love was certainly regarded by the editors as faithful and passionate, but without unseemly allusions to forbidden practices...Emotional and even physical closeness of two males did not seem to concern the editors of the story, nor was such a relationship prohibited by Leviticus." Homosociality is not seen as being part of the sexual taboo in the biblical world.[9]

Medieval and Renaissance allusions

Medieval literature occasionally drew upon the Biblical relationship between David and Jonathan to underline strong personal and intimate friendships between men. The story has also frequently been used as a coded reference to homoerotic relations when the mention was socially discouraged or even punished.

The anonymous Life of Edward II, ca. 1326 AD, wrote: "Indeed I do remember to have heard that one man so loved another. Jonathan cherished David, Achilles loved Patroclus." We are also told that King Edward II wept for his dead lover Piers Gaveston as:"...David had mourned for Jonathan." Roger of Hoveden, a twelfth century chronicler, also deliberately drew comparisons in his description of "The King of France (Philip II Augustus) [who] loved him (Richard the Lionheart) as his own soul."

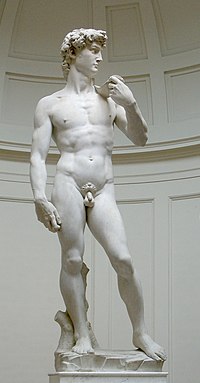

Both the Renaissance artists Donatello and Michelangelo brought out strong homoerotic elements in their respective sculptures depicting the youthful David.

Abraham Cowley's "Davideis" (1656) as an epic poem deals abundantly with the friendship motif. George Frederic Handel's oratorio Saul (1739) contains a setting of David's lament upon the death of Jonathan.

Modern interpretations

Homoeroticism

The Biblical account of David and Jonathan has been read by some as the story of two lovers.

"La Somme le Roy", 1290 AD; French illuminated ms (detail); British Museum

Some modern scholars, writers and activists have interpreted the love between David and Jonathan as more intimate than platonic friendship. This was first pioneered by Horner, then rehearsed by Boswell and Halperin.[10][11] This interpretation views the bonds the men shared as romantic love, regardless of whether or not the relationship was physically consummated. Jonathan and David cared deeply about each other in a way that was arguably more tender and intimate than a platonic friendship.

David's praise in 2 Samuel 1:26 for Jonathan's 'love' (for him) over the 'love' of women is considered evidence for same-sex attraction, along with Saul's exclamation to his son at the dinner table, "I know you have chosen the son of Jesse - which is a disgrace to yourself and the nakedness of your mother!" The "choosing" (bahar) may indicate a permanent choice and firm relationship, and the mention of "nakedness" (erwa) could be interpreted to convey a negative sexual nuance, giving the impression that Saul saw something indecent in Jonathan's and David's relationship [12].

Some also point out that the relationship between the two men is addressed with the same words and emphasis as other love relationships in the Hebrew Testament, whether heterosexual or between God and people: e.g. ahava or אהבה.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

When they are alone together, David confides that he has "found grace in Jonathan's eyes", a phrase proponents say normally refers to romantic or physical attraction. Throughout the passages, David and Jonathan consistently affirm and reaffirm their love and devotion to each other, and Jonathan is willing to betray his father, family, wealth, and traditions for David.

That there is more than mere homosociality in the dealings of David and Jonathan is asserted by two recent studies: the Biblical scholar Susan Ackerman [21], and the Orientalist Jean-Fabrice Nardelli [22]. Ackerman and Nardelli argue that the narrators of the books of Samuel encrypted same-sex allusions in the texts where David and Jonathan interact so as to insinuate that the two heroes were lovers. Ackerman explains this as a case of liminal, viz. transitory, homosexuality, deployed by the redactors as a textual means to assert David's rights against Jonathan's: the latter willingly alienated his princely status by bowing down, sexually speaking, to the former. Nardelli disagrees and argues that the various covenants Jonathan engaged David into as the superior partner gradually elevated David's status and may be seen as marriage-like.

Although David was married, David himself articulates a distinction between his relationship with Jonathan and the bonds he shares with women. David is married to many women, one of whom is Jonathan's sister Michal, but the Bible does not mention David loving Michal (though it is stated that Michal loves David).

Counter arguments

Traditional religious apologists point out that neither the books of Samuel nor Jewish tradition documents sanctioned romantic or erotic physical intimacy between the two characters, which the Bible elsewhere makes evident when between heterosexuals, most supremely in the Song of Solomon. It is also known that covenants were common, and that the word is never used to denote marriage between man and women,[23] and that marriage was a public event and included customs not seen in this story.[24][25]

The platonic interpretation of David and Jonathan's relationship is seen as being advocated by some Christian writers particularly for theological and methodological reasons. Two modern advocates named are Robert A. J. Gagnon,[26] and the Assyriologist Markus Zehnder.[27], and as such is consistent with popular theological views condemning same sex relations.[28]

Those who hold to this position on David and Jonathan most typically work from the theological foundation of Biblical infallibility and a more literalistic approach to exegesis, so that while interpretations are understood within the context of their particular literary genres, a wide range of metaphorical meanings of the historical narratives, in particular, are disallowed.[29][30][31][32]

The disrobing aspect is seen as partial (especially in the Hebrew), that of his robe and outer garments, his sword, bow and “girdle," which denotes part of a soldiers armor in 2Samuel 20:8 and 2Kings 3:21. In addition, this action is evidenced as having a clear ceremonial precedent under Moses, in which God commanded, "And strip Aaron of his garments, and put them upon Eleazar his son", [33] in transference of the office of the former upon the latter. In like manner, Jonathan would be symbolically and prophetically transferring the kingship of himself (as the normal heir) to David, which would come to pass.[34][35][36]

In platonic respects, such as in sacrificial loyalty and zeal for the kingdom, Jonathan's love is seen as surpassing that of romantic or erotic affection,[37] especially that of the women David had known up until that time. The grammatical and social difficulties are pointed out in respect to 1 Samuel 18:21[38], as well as the marked difference in the Bible between sensual kissing (as in Song of Songs) and the cultural kiss of Near Eastern culture whether in greeting or as expression of deep affection between friends and family (as found throughout the Old and New Testaments).[39] The strong emotive language expressed by David towards Jonathan is also argued to be akin to that of platonic expressions in more expressive or pre-urban cultures.[40]

Literature and legacy

At his 1895 trial, Oscar Wilde cited the example of David and Jonathan in support of "the love that dare not speak its name": Such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare.[41]

Contemporary American literature also show attempts at fictionalisation of the David narrative. Gladys Schmitt's 1946 novel David the King took a risk, especially for its time, in portraying David's relationship with Jonathan as overtly homoerotic, but was ultimately panned by critics as a bland rendition of the title character.

In Thomas Burnett Swann's Biblical fantasy novel How are the Mighty Fallen (1974) David and Jonathan are explicitly stated to be lovers. Moreover, Jonathan is a member of a winged semi-human race (possibly nephilim), one of several such races co-existing with humanity but often persecuted by it.

The erotics of the battle between David and Goliath feature in Richard Howard's poem ''The Giant on Giant Killing" in his book Fellow Feelings (1976).

Allan Massie wrote "King David" (1995), a novel about David's career which portrays the king's relationship to Jonathan and others as openly homosexual.

In modern times, in his Lambeth essay of December 2007, James Jones the Bishop of Liverpool, drew particular attention to the relationship between David and Jonathan,[42] describing their friendship as:

...emotional, spiritual and even physical. There was between them a deep emotional bond that left David grief-stricken when Jonathan died. But not only were they emotionally bound to each other they expressed their love physically. Jonathan stripped off his clothes and dressed David in his own robe and armour. With the candour of the Eastern World that exposes the reserve of Western culture they kissed each other and wept openly with each other. This intimate relationship was sealed before God - it was not just a spiritual bond it became covenantal. He concludes by affirming: Here is the Bible bearing witness to love between two people of the same gender

Nissinen has concluded[43]:

Perhaps these homosocial relationships, based on love and equality, are more comparable with modern homosexual people's experience of themselves than those texts that explicity speak of homosexual acts that are aggressive, violent expressions of domination and subjection.

See also

Notes

- ^ 1 Sam. 18:1–4

- ^ 1 Sam. 19:1–2

- ^ 1 Sam. 20:3

- ^ 1 Sam. 20:16–17

- ^ 1 Sam. 20:30

- ^ 2 Sam. 1:26)

- ^ James B. DeYoung, Homosexuality, p. 290

- ^ Prof. Dr. Robert A. J. Gagnon

- ^ Martti Nissinen, Kirsi Stjerna, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, p. 56

- ^ Boswell, John. Same-sex Unions in Premodern Europe. New York: Vintage, 1994. (pp. 135-137)

- ^ Halperin, David M. One Hundred Years of Homosexuality. New York: Routledge, 1990. (p. 83)

- ^ Martti Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, Minneapolis, 1998

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_views_of_love#Jewish

- ^ Hebrew word #160

- ^ Gen. 29:20

- ^ 2 Sam. 13:15

- ^ Pro. 5:19Template:Bibleverse with invalid book

- ^ Sgs. 2:4–7Template:Bibleverse with invalid book

- ^ Sgs. 3:5–10Template:Bibleverse with invalid book

- ^ Sgs. 5:8Template:Bibleverse with invalid book)

- ^ When Heroes Love:. The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David (New York & Chichester, Columbia University Press, 2005), pp. 165-231

- ^ Homosexuality and Liminality in the Gilgamesh and Samuel (Amsterdam, Hakkert, 2007), pp. 28-63

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

- ^ Albert Barnes, Judges 14:10

- ^ Sketches of Jewish Social Life. Cp. 9 (Edersheim)

- ^ The Bible and Homosexual Practice. Texts and Hermeneutics (Nashville, Abingdon Press, 2001), pp. 146-154

- ^ Observations on the Relationship Between David and Jonathan and the Debate on Homosexuality, Westminster Theological Journal 69 (2007), pp. 127-174

- ^ "Welcoming But Not Affirming," by Stanley J. Grenz

- ^ The Authority Of God's Law Today, Greg L. Bahnsen

- ^ Hermeneutical issues in the use of the Bible to justify the acceptance of homosexual practice

- ^ Guenther Haas, Hermeneutical issues in the use of the bible to justify the acceptance of homosexual practice

- ^ Lionel Windsor, The Bible and Homosexuality

- ^ Numbers 20:26; cf. Esther 3:6

- ^ Gagnon, The Bible and Homosexual Practice, pp. 146-54

- ^ Markus Zehnder, “Observations on the Relationship between David and Jonathan and the Debate on Homosexuality,” Westminster Theological Journal 69.1 [2007]: 127-74)

- ^ Thomas E Schmidt, “Straight or Narrow?”

- ^ Matthew Henry

- ^ Keil and Delitzsch; and is seen as referring to Merab and Michal: John Gill; T. Bab. Sanhedrin, fol. 19. 2.

- ^ Gagnon, ibid

- ^ Regan, P. C; Jerry, D; Narvaez, M; Johnson, D. Public displays of affection among Asian and Latino heterosexual couples. Psychological Reports. 1999;84:1201–1202

- ^ Neil McKenna, The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde, London, 2004

- ^ http://www.liverpool.anglican.org/index.php?p=215

- ^ Martti Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, Minneapolis, 1998

References

- Jonathan Loved David: Homosexuality in Biblical Times (ISBN 0-664-24185-9) by Tom Horner, Ph.D. (pgs 15-39)

- What the Bible Really Says About Homosexuality (ISBN 1-886360-09-X) by Daniel A. Helminiak, Ph.D. (pgs 123-127)

- Lord Given Lovers: The Holy Union of David & Jonathan (ISBN 0-595-29869-9) by Christopher Hubble. (entire)

- "The Significance of the Verb Love in the David-Jonathan Narratives in 1 Samuel" by J. A. Thompson from the Vestus Testamentum 24 (pgs 334-338)

- John Boswell's Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe (pgs. 67-71)

- Craig Williams' Yale University Ph.D. Dissertation Homosexuality and the Roman Man: A Study in the Cultural Construction of Sexuality (pg. 319).

- Martti Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, Minneapolis, 1998