Sunburn

| Sunburn | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Dermatology |

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (February 2008) |

A sunburn is a burn to living tissue such as skin produced by overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, commonly from the sun's rays. Usual mild symptoms in humans and animals are red or reddish skin that is hot to the touch, general fatigue, and mild dizziness. An excess of UV-radiation can be life-threatening in extreme cases. Exposure of the skin to lesser amounts of UV radiation will often produce a suntan.

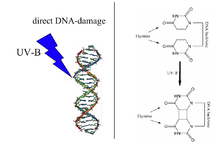

Excessive UV-radiation is the leading cause of primarily non malignant skin tumors.[1][2] Sunscreen is widely agreed to prevent sunburn, although a minority of scientists argue that it may not effectively protect against malignant melanoma, which is either caused by a different part of the ultraviolet spectrum or, according to others, not caused by sun exposure at all.[3][4] Clothing, including hats, is considered the preferred skin protection method. Moderate sun tanning without burning can also prevent subsequent sunburn, as it increases the amount of melanin, a skin photoprotectant pigment that is the skin's natural defense against overexposure. Importantly, sunburn and the increase in melanin production are both triggered by direct DNA damage. When the skin cells' DNA is damaged by UV radiation, type I cell-death is triggered and the skin is replaced.[5] Malignant melanoma may occur as a result of indirect DNA damage if the damage is not properly repaired. Proper repair occurs in the majority of DNA damage, and as a result not every exposure to UV results in cancer. The only cure for sunburn is slow healing, although some skin creams can help with the symptoms.

Cause

Sunburn is caused by the UV-radiation from the sun. UV-radiation from artificial sources, such as welding arcs and the lamps used in sunbeds and ultraviolet germicidal irradiation, can also cause sunburn. It is a reaction of the body to the direct DNA damage which can result from the excitation of DNA by UV-B light. This damage is mainly the formation of a thymine-thymine dimer. The damage is recognized by the body, and it triggers several defense mechanisms. These include DNA repair to revert the damage and increased melanin production to prevent future damage. Melanin transforms UV-photons quickly into harmless amounts of heat without generating free radicals and is therefore an excellent photoprotectant against direct and indirect DNA damage.

On an evolutionary level, the sunburn may have developed as a warning signal that deters humans from sun seeking behaviour which induces infertility.[6] Importantly it has been shown that protecting against sunburn with chemical sunscreens does not imply protection against other damaging effects of UV-radiation.[7]

Sunburn and skin cancer

Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation causes dangerous sunburns and increases the risk of two types of skin cancer: basal-cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.[8][9]

Controversy over sunscreen

The statement that "sunburn causes skin cancer" is adequate when it refers to basal-cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. But it is false when it comes to malignant melanoma (see picture: UVR sunburn melanoma).[10] The statistical correlation between sunburn and melanoma is due to a common cause — the UV-radiation. However, they are generated via two different mechanisms: direct DNA damage is ascribed by many medical doctors to a change in behaviour of the sunscreen user due to a false sense of security afforded by the sunscreen. (Other researchers blame insufficient correction for confounding factors; light skinned individuals versus indirect DNA damage.)

Topically applied sunscreens block the UV rays as long as they do not penetrate into the skin. This prevents sunburn, suntanning, and skin cancer. If however the sunscreen filter is absorbed into the skin it only prevents the sunburn but it increases the amount of free radicals which in turn increases the risk for malignant melanoma. The harmful effect of photoexcited sunscreen filters on living tissue has been shown in many photobiological studies.[11][12][13][14] Whether sunscreen prevents or promotes the development of melanoma depends on the relative importance of the protective effect from the topical sunscreen and the harmful effects of the absorbed sunscreen.

The use of sunscreen is known to prevent the direct DNA damage that causes sunburn and the two most common forms of skin cancer, basal-cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.[15] However, if sunscreen penetrates into the skin, it promotes the indirect DNA damages, which cause the most lethal form of skin cancer, malignant melanoma.[16] This form of skin cancer is rare, but it is responsible for 75% of all skin cancer-related deaths. Increased risk of malignant melanoma in sunscreen users has been the subject of many epidemiological studies.[3][4][17][18][19][20][21]

Other risk factors

Location

source: NOAA.

Because of variations in the intensity of UV-radiation passing through the atmosphere, the risk of sunburn increases with proximity to the tropic latitudes, located between 23.5° north and south latitude. Everything else being equal (e.g. cloud cover, ozone layer, terrain, etc.), over the course of a full year, each location within the tropic or polar regions receives approximately the same amount of UV radiation. In the temperate zones between 23.5° and 66.5°, UV radiation varies by latitude. The higher the latitude, the lower the intensity of the UV rays. On a minute-by-minute basis, the amount of UV radiation is dependent on the angle of the sun. This is easily determined by the height ratio of any object to the size of its shadow. The greatest risk is at solar noon, when shadows are at their minimum and the sun's radiation passes more directly through the atmosphere. Regardless of one's latitude (assuming no other variables), equal shadow lengths mean equal amounts of UV radiation.

Pharmaceutical products

Sunburn can also be caused by pharmaceutical products that sensitise some users to UV radiation. Certain antibiotics, oral contraceptives, and tranquillizers have this effect.[22] People with fair hair and/or freckles generally have a greater risk of sunburn than others because of their lighter skin tone.[23]

Ozone depletion

In recent years, the incidence and severity of sunburn has increased worldwide, especially in the southern hemisphere, because of damage to the ozone layer. Ozone depletion and the seasonal ozone hole have led to dangerously high levels of UV radiation.[24] Incidence of skin cancer in Queensland, Australia has risen to 75 percent among those over 64 years of age by about 1990, presumably due to thinning of the ozone layer.[25] However it was pointed out by Garland et al. that the melanoma rate in Queensland had a steep rise before the rest of Australia experienced the same increase of melanoma numbers. They blamed the vigorous promotion of sunscreen, which was first done in Queensland, while sunscreen use was encouraged in the rest of Australia some time later. An effect that would stem from the ozone depletion cannot obey the borderline of different areas of Australia, but sunscreen endorsement programs can.[3] Another study from Norway points out that there had been no change of the ozone layer during the period 1957 to 1984, yet the yearly incidence of melanoma in Norway had increased by 350% for men and by 440% for women. They concluded that in Norway "ozone depletion is not the cause of the increase in skin cancers".[26]

Popularity of tanning

Suntans, which naturally develop in some individuals as a protective mechanism against the sun, are viewed by many in the Western world as desirable.[27] This has led to an increased exposure to UV-radiation from the natural sun and from solaria.

Symptoms

Typically there is initial redness (erythema), followed by varying degrees of pain, proportional in severity to both the duration and intensity of exposure.

Other symptoms are edema, itching, peeling skin, rash, nausea and fever. Also, a small amount of heat is given off from the burn caused by the concentration of blood in the healing process, giving a warm feeling to the affected area. Sunburns may be first- or second-degree burns.

One should immediately speak to a dermatologist if a skin lesion appears suddenly, with asymmetrical appearance, darker edges than center, that changes color, or becomes larger than 1/4 inch (6 mm). (see Melanoma)

Variations

Minor sunburns typically cause nothing more than slight redness and tenderness to the affected areas. In more serious cases, blistering can occur. Extreme sunburns can be painful to the point of debilitation and may require hospital care.

Duration

Sunburn can occur in less than 15 minutes, and in seconds when exposed to non-shielded welding arcs or other sources of intense ultraviolet light. Nevertheless, the inflicted harm is often not immediately obvious.

After the exposure, skin may turn red in as little as 30 minutes but most often takes 2 to 6 hours. Pain is usually most extreme 6 to 48 hours after exposure. The burn continues to develop for 24 to 72 hours occasionally followed by peeling skin in 3 to 8 days. Some peeling and itching may continue for several weeks.

Protection

Skin

It is advisable to consult a UV index to determine what level of protection is necessary. Potential forms of protection include wearing long-sleeved garments and wide-brimmed hats, and using an umbrella when in the sun. Minimization of sun exposure between the hours of 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. is also recommended. It is important to keep in mind that locations that use daylight saving time can have the most intense rays significantly later than 12 pm. Usually it will be around 1 pm, but in places like western Europe (where standard/winter time is already about an hour ahead of the sun, excluding the UK) DST/Summer Time can make it be later than 2 pm.

Commercial preparations are available that block UV light, known as sunscreens or sunblocks. They have a Sunburn Protection Factor (SPF) rating, based on the sunblock's ability to suppress sunburn: The higher the SPF rating, the lower the amount of direct DNA damage.

A sunscreen rated SPF10 blocks 90% UVB (but only as long as it did not penetrate into the skin); an SPF20 rated sunscreen blocks 95%. It is best to use a broad spectrum sunscreen to protect against both UVA and UVB radiation. It is prudent to use waterproof formulations if one plans to engage in water-based activities. Modern sunscreens contain filters for UVA radiation as well as UVB. Note that the stated protection factors are only correct if 2 μl of sunscreen is applied per square cm of exposed skin. This translates into about 28 ml (1 oz) to cover the whole body of an adult male, which is much more than many people use in practice.

Contrary to the common advice that sunscreen should be reapplied every 2–3 hours, research has shown that the best protection is achieved by application 15 to 30 minutes before exposure, followed by one reapplication 15 to 30 minutes after the sun exposure begins. Further reapplication is only necessary after activities such as swimming, sweating, and rubbing.[28] This varies based on the indications and protection shown on the label — from as little as 80 minutes in water to a few hours,1 depending on the product selected.

When one is exposed to any artificial source of occupational UV, special protective clothing (for example, welding helmets/shields) should be worn.

There is also evidence that common foods may have some protective ability against sunburn if taken for a period before the exposure.[29] Beta-carotene and lycopene, chemicals found in tomatoes and other fruit, have been found to increase the skin's ability to resist the effects of UV light. In a 2007 study, after about 10–12 weeks of eating tomato-derived products, a decrease in sensitivity toward UV was observed in volunteers. Ketchup and tomato puree are both high in lycopene.[30] Dark chocolate rich in flavonoids has also been found to have a similar effect if eaten for long periods before exposure.

Eyes

The eyes are also sensitive to sun exposure, and wrap-around sunglasses which block UV light should also be worn. UV light has been implicated in pterygium and cataract development. For example, concentrated clusters of melanin, commonly known as freckles, are often found within the iris.

It has been argued that the optic nerve stimulates the pituitary gland to produce a hormone that triggers the melanocytes in the skin to make more melanin. When wearing sunglasses, less sunlight reaches the optic nerve which in turn causes less warning to be sent to the pituitary gland and thus less melanin is made. Since melanin is required in greater quantity, one might be limiting cells from producing a necessary compound to prevent the damaging effects of ultraviolet radiation, and thus increasing the chance of sunburn. [31]

Treatment

The most important aspect of sunburn care is to avoid exposure to the sun while healing and to take precautions to prevent future burns. The best treatment for most sunburns is time. Given a few weeks, they will heal; however, there are a number of treatments that help manage the discomfort or facilitate the healing process. Blistered skin, with or without open sores, should heal on its own, but consult appropriate sources for suggestions about whether or not you may need medical attention.

Topical applications

- Lidocaine or Benzocaine can be administered to the spot of injury and will generally negate most of the pain. Lidocaine and benzocaine are a popular FDA approved local anesthetic pain reliever for sunburns and available at most drugstores in the United States in the form of ointment or spray.

The pain and burning associated with a sunburn can be relieved with a number of different remedies applied to the burn site. The skin can be hydrated by applying topical products containing Aloe vera and/or vitamin E, which reduce inflammation. Hydrocortisone cream may also help reduce inflammation and itching.

Avoid the use of butter; This is a false remedy which can prevent healing and damage skin.[32] When treating open sores caused by a sunburn, like any other open skin wound, it is best to avoid lotions or other directly-applied ointments. However, antibacterial solutions and gauze can prevent skin infections.

There are two home remedies which have been known to help. One method involves applying a clean washcloth soaked with cool (not cold) milk, in the form of a cold compress. In addition to the cool temperature, a protein film will form to soothe the pain and the lactic acid will help reduce inflammation.[33] A solution of diluted white cider vinegar (approx. 1 cup in a tub of water) applied in a similar fashion may also ease pain.[34]

Oral medication

Sunburns can cause headaches or a mild fever in addition to the pain, so an analgesic may be indicated.[35] Acetaminophen can help to relieve the pain. Taking NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or naproxen may help to reduce pain and inflammation. Aspirin may also be used, but DO NOT give aspirin to children as can cause Reye's syndrome[32]

See also

- Sun unit

- Hyperthermia (heat stroke)

- Windburn

Notes

- ^ World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer "Do sunscreens prevent skin cancer" Press release No. 132, June 5, 2000

- ^ World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer "Solar and ultraviolet radiation" IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 55, November 1997

- ^ a b c Garland C, Garland F, Gorham E (1992). "Could sunscreens increase melanoma risk?". Am J Public Health. 82 (4): 614–5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.82.4.614. PMID 1546792.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Westerdahl J, Ingvar C, Mâsbäck A, Olsson H (2000). "Sunscreen use and malignant melanoma". Int. J. Cancer. 87 (1): 145–50. doi:10.1002/1097-0215(20000701)87:1<145::AID-IJC22>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 10861466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Westerdahl2000" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Sunburn at eMedicine

- ^ "The evolution of human skin coloration" (PDF).

- ^ Wolf P; Donawho C K; Kripke M L (1994). "Effect of Sunscreens on UV radiation-induced enhancements of melanoma in mice". J. Nat. Cancer. Inst. 86: 99–105. doi:10.1093/jnci/86.2.99. PMID 8271307.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer "Do sunscreens prevent skin cancer" Press release No. 132, June 5, 2000

- ^ World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer "Solar and ultraviolet radiation" IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 55, November 1997

- ^ Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C; et al. (2002). "Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer". Nature. 417 (6892): 949–54. doi:10.1038/nature00766. PMID 12068308.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Armeni T, Damiani E, Battino M, Greci L, Principato G (2004). "Lack of in vitro protection by a common sunscreen ingredient on UVA-induced cytotoxicity in keratinocytes". Toxicology. 203 (1–3): 165–78. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2004.06.008. PMID 15363592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Knowland J, McKenzie EA, McHugh PJ, Cridland NA (1993). "Sunlight-induced mutagenicity of a common sunscreen ingredient". FEBS Lett. 324 (3): 309–13. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(93)80141-G. PMID 8405372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mosley, C N; Wang, L; Gilley, S; Wang, S; Yu, H (2007). "Light-Induced Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of a Sunscreen Agent, 2-Phenylbenzimidazol in Salmonella typhimurium TA 102 and HaCaT Keratinocytes". Internaltional Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 4 (2): 126–31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xu C, Green A, Parisi A, Parsons PG (2001). "Photosensitization of the sunscreen octyl p-dimethylaminobenzoate by UVA in human melanocytes but not in keratinocytes". Photochem. Photobiol. 73 (6): 600–4. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2001)073<0600:POTSOP>2.0.CO;2. PMID 11421064.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Health Report - 13/09/99: Skin Cancer and Sunscreen

- ^ Hanson KM, Gratton E, Bardeen CJ (2006). "Sunscreen enhancement of UV-induced reactive oxygen species in the skin". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41 (8): 1205–12. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.011. PMID 17015167.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Autier P, Doré JF, Schifflers E; et al. (1995). "Melanoma and use of sunscreens: an EORTC case-control study in Germany, Belgium and France. The EORTC Melanoma Cooperative Group". Int. J. Cancer. 61 (6): 749–55. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910610602. PMID 7790106.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weinstock MA (1999). "Do sunscreens increase or decrease melanoma risk: an epidemiologic evaluation". J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 4 (1): 97–100. doi:10.1038/sj.jidsp. PMID 10537017.

- ^ Vainio H, Bianchini F (2000). "Cancer-preventive effects of sunscreens are uncertain". Scand J Work Environ Health. 26 (6): 529–31. PMID 11201401.

- ^ Wolf P, Quehenberger F, Müllegger R, Stranz B, Kerl H. (1998). "Phenotypic markers, sunlight-related factors and sunscreen use in patients with cutaneous melanoma: an Austrian case-control study". Melanoma Res. 8 (4): 370–378. doi:10.1097/00008390-199808000-00012. PMID 9764814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Graham S, Marshall J, Haughey B; et al. (1985). "An inquiry into the epidemiology of melanoma". Am. J. Epidemiol. 122 (4): 606–19. PMID 4025303.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Avoiding Sun-Related Skin Damage" - No longer available

- ^ Sunburn-Topic Overview

- ^ van der Leun, J.C., and F.R. de Gruijl (1993). Influences of ozone depletion on human and animal health. Chapter 4 in UV-B radiation and ozone depletion: Effects on humans, animals, plants, microorganisms, and materials. p. 95-123.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Al Gore, "Earth in the Balance, Ecology and the Human Spirit"', 1992

- ^ Moan J, Dahlback A (1992). "The relationship between skin cancers, solar radiation and ozone depletion". Br. J. Cancer. 65 (6): 916–21. PMID 1616864.

- ^ Healthwise Incorporated (March 27). "Suntan".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Text "accessmonthday August 26" ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Diffey BL (2001). "When should sunscreen be reapplied?". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 45 (6): 882–5. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.117385. PMID 11712033.

- ^ Stahl W, Sies H (2007). "Carotenoids and flavonoids contribute to nutritional protection against skin damage from sunlight". Mol. Biotechnol. 37 (1): 26–30. PMID 17914160.

- ^ Neukam K, Stahl W, Tronnier H, Sies H, Heinrich U (2007). "Consumption of flavanol-rich cocoa acutely increases microcirculation in human skin". Eur J Nutr. 46 (1): 53–6. doi:10.1007/s00394-006-0627-6. PMID 17164979.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sharon Moalem, Jonathan Prince. Survival of the Sickest: A Medical Maverick Discovers Why We Need Disease. February 2007.

- ^ a b MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Sunburn first aid

- ^ "Sunburn Remedies".

- ^ "Got Sunburn? Get Milk".

- ^ Heathwise Incorporated (January 9, 2006). "Sunburn – Home Treatment". Retrieved 2006-08-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Agar NS, Halliday GM, Barnetson RS, Ananthaswamy HN, Wheeler M, Jones AM (2004). "The basal layer in human squamous tumors harbors more UVA than UVB fingerprint mutations: a role for UVA in human skin carcinogenesis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (14): 4954–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401141101. PMC 387355. PMID 15041750.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Baron ED, Fourtanier A, Compan D, Medaisko C, Cooper KD, Stevens SR (2003). "High ultraviolet A protection affords greater immune protection confirming that ultraviolet A contributes to photoimmunosuppression in humans". J. Invest. Dermatol. 121 (4): 869–75. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12485.x. PMID 14632207.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hall HI, Saraiya M, Thompson T, Hartman A, Glanz K, Rimer B (2003). "Correlates of sunburn experiences among U.S. adults: results of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey". Public Health Rep. 118 (6): 540–9. PMC 1497591. PMID 14563911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Haywood R, Wardman P, Sanders R, Linge C (2003). "Sunscreens inadequately protect against ultraviolet-A-induced free radicals in skin: implications for skin aging and melanoma?". J. Invest. Dermatol. 121 (4): 862–8. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12498.x. PMID 14632206.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - NOAA UV-Index Summary with Data Graphs

External links

- WebMD: When to see a doctor

- Tips and facts to know before playing in the sun

- Information on Treating and Preventing Sunburn from The Skin Cancer Foundation

- Sunburn Damage to Trees and Plants: and Prevention

- Sun Protection Tips

- Protecting Kids from the Sun

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Sunburn

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Sunburn First Aid

- Avoid sunburn - calculate your personal safe sunbathing time online, based on skin type and UV-index

- UV Information

- Check UV Index In Your City

- Shade structures allow outdoor fun while mitigating burn risk

- Sunblock Iphone program Iphone program that uses gps to get positional UV index and suggest SPF