Human musculoskeletal system

The human musculoskeletal system (also known as the locomotor system) is an organ system that gives humans and animals the ability to move using the muscular and skeletal systems. The musculoskeletal system provides form, stability, and movement to the human and animal body.

It is made up of the body's bones (the skeleton), muscles, cartilage, tendons, ligaments, joints, and other connective tissue (the tissue that supports and binds tissues and organs together). The musculoskeletal system's primary functions include supporting the body, allowing motion, and protecting vital organs.[1] The skeletal portion of the system serves as the main storage system for calcium and phosphorus and contains critical components of the hematopoietic system.[2]

This system describes how bones are connected to other bones and muscle fibers via connective tissue such as tendons and ligaments. The bones provide the stability to a body in analogy to iron rods in concrete construction. Muscles keep bones in place and also play a role in movement of the bones. To allow motion different bones are connected by joints. Cartilage prevents the bone ends from rubbing directly on to each other. Muscles contract (bunch up) and extend (stretch) to move the bone attached at the joint.

There are, however, diseases and disorders that may adversely affect the function and overall effectiveness of the system. These diseases can be difficult to diagnose due to the close relation of the musculoskeletal system to other internal systems. The musculoskeletal system refers to the system having its muscles attached to an internal skeletal system and is necessary for humans to move to a more favorable position.

Subsystems

Skeletal

The Skeletal System serves many important functions; it provides the shape and form for our bodies in addition to supporting, protecting, allowing bodily movement, producing blood for the body, and storing minerals.[3] The number of bones in the human skeletal system is a controversial topic. Humans are born with about 300 to 350 bones, however, many bones fuse together between birth and maturity. As a result an average adult skeleton consists of 208 bones. The number of bones varies according to the method used to derive the count. While some consider certain structures to be a single bone with multiple parts, others may see it as a single part with multiple bones.[4] There are five general classifications of bones. These are Long bones, Short bones, Flat bones, Irregular bones, and Sesamoid bones. The human skeleton is composed of both fused and individual bones supported by ligaments, tendons, muscles and cartilage. It is a complex structure with two distinct divisions. These are the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton.[5]

Function

The Skeletal System serves as a framework for tissues and organs to attach themselves to. This system acts as a protective structure for vital organs. Major examples of this are the brain being protected by the skull and the lungs being protected by the rib cage.

Located in long bones are two distinctions of bone marrow (yellow and red). The yellow marrow has fatty connective tissue and is found in the marrow cavity. During starvation, the body uses the fat in yellow marrow for energy.[6] The red marrow of some bones is an important site for blood cell production, approximately 2.6 million red blood cells per second in order to replace existing cells that have been destroyed by the liver.[3] Here all erythrocytes, platelets, and most leukocytes form in adults. From the red marrow, erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes migrate to the blood to do their special tasks.

Another function of bones is the storage of certain minerals. Calcium and phosphorus are among the main minerals being stored. The importance of this storage "device" helps to regulate mineral balance in the bloodstream. When the fluctuation of minerals is high, these minerals are stored in bone; when it is low it will be withdrawn from the bone.

Muscular

There are three types of muscles - cardiac, skeletal, and smooth. Smooth muscles are used to control the flow of substances within the lumens of hollow organs, and are not consciously controlled. Skeletal and cardiac muscles have striations that are visible under a microscope due to the components within their cells. Only skeletal and smooth muscles are part of the musculoskeletal system and only the skeletal muscles can move the body. Cardiac muscles are found in the heart and are used only to circulate blood; like the smooth muscles, these muscles are not under conscious control. Skeletal muscles are attached to bones and arranged in opposing groups around joints.[7] Muscles are innervated, to communicate nervous energy to[8], by nerves, which conduct electrical currents from the central nervous system and cause the muscles to contract.[9]

Contraction initiation

In mammals, when a muscle contracts, a series of reactions occur. Muscle contraction is stimulated by the motor neuron sending a message to the muscles from the somatic nervous system. Depolarization of the motor neuron results in neurotransmitters being released from the nerve terminal. The space between the nerve terminal and the muscle cell is called the neuromuscular junction. These neurotransmitters diffuse across the synapse and bind to specific receptor sites on the cell membrane of the muscle fiber. When enough receptors are stimulated, an action potential is generated and the permeability of the sarcolemma is altered. This process is known as initiation.[10]

Nervous

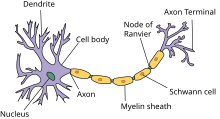

Nervous tissue is made of two general cell types. Neurons, the conducting cell type, transmit nerve messages and Glial cells, the non-conducting cell type, serve as support cells and help to protect the neurons.[11] The neuron is the cell that receives and sends the messages received from chemical reactions. Humans have approximately 100 billion neurons in their brain alone.[11] All neurons have three parts. Dendrites receive information from another cell and trasnport the message to the cell body. The cell body, or soma contains the organelles typical of eukaryotic cells and the axon conducts messages away from the cell body, acting as a transport for the message.

The junction between a nerve cell and another cell is called a synapse. Messages travel within the neuron as an electrical action potential. The space between two cells is known as the synaptic cleft.To cross the synaptic cleft requires the actions of neurotransmitters, stored in small synaptic vesicles clustered at the tip of the axon.

Joints

Joints are structures that connect individual bones and may allow bones to move against each other to cause movement. There are two divisions of joints, diarthroses which allow extensive mobility between two or more articular heads, and false joints or synarthroses, joints that are immovable, that allow little or no movement and are predominantly fibrous. Synovial joints, joints that are not directly joined, are lubricated by a solution called synovia that is produced by the synovial membranes. This fluid lowers the friction between the articular surfaces and is kept within an articular capsule, binding the joint with its taut tissue.[5]

Tendons

A tendon is a tough, flexible band of fibrous connective tissue that connects muscles to bones.[12] Muscles gradually become tendon as the cells become closer to the origins and insertions on bones, eventually becoming solid bands of tendon that merge into the periosteum of individual bones. As muscles contract, tendons transmit the forces to the rigid bones, pulling on them and causing movement.

Ligaments

A ligament is a small band of dense, white, fibrous elastic tissue.[5] Ligaments connect the ends of bones together in order to form a joint. Most ligaments limit dislocation, or prevent certain movements that may cause breaks. Since they are only elastic they increasingly lengthen when under pressure. When this occurs the ligament may be susceptible to break resulting in an unstable joint.

Ligaments may also restrict some actions: movements such as hyperextension and hyperflexion are restricted by ligaments to an extent. Also ligaments prevent certain directional movement.[13]

Bursa

A bursa is a small fluid-filled sac made of white fibrous tissue and lined with synovial membrane. Bursa may also be formed by a synovial membrane that extends outside of the join capsule.[6] It provides a cushion between bones and tendons and/or muscles around a joint; bursa are filled with synovial fluid and are found around almost every major joint of the body.

Diseases and disorders

Because many other body systems, including the vascular, nervous, and integumentary systems, are interrelated, disorders of one of these systems may also affect the musculoskeletal system and complicate the diagnosis of the disorder's origin. Diseases of the musculoskeletal system mostly encompass functional disorders or motion discrepancies; the level of impairment depends specifically on the problem and its severity. Articular (of or pertaining to the joints)[14] disorders are the most common. However, also among the diagnoses are: primary muscular diseases, neurologic (related to the medical science that deals with the nervous system and disorders affecting it)[15] deficits, toxins, endocrine abnormalities, metabolic disorders, infectious diseases, blood and vascular disorders, and nutritional imbalances. Disorders of muscles from another body system can bring about irregularities such as: impairment of ocular motion and control, respiratory dysfunction, and bladder malfunction. Complete paralysis, paresis, or ataxia may be caused by primary muscular dysfunctions of infectious or toxic origin; however, the primary disorder is usually related to the nervous system, with the muscular system acting as the effector organ, an organ capable of responding to a stimulus, especially a nerve impulse.[2]

Notes

- ^ Mooar, Pekka (2007). "Introduction". Merck Manual. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ^ a b Kahn, Cynthia (2008). Musculoskeletal System Introduction: Introduction. NJ, USA: Merck & Co., Inc.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Applegate, Edith. "The Skeletal System". Retrieved 2009-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Engelbert, Phillis (2009). "The Human Body / How Many Bones Are In The Human Body?". U·X·L Science Fact Finder. eNotes.com, Inc. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Gary, Farr (2002-06-25). "The Musculoskeletal System". Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ^ a b "Skeletal System". 2001. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Mooar, Pekka (2007). "Muscles". The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|access date=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "innervated". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com, LLC. 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|access date=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Bárány, Michael (2002). "SMOOTH MUSCLE".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|access date=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Mechanism of Muscle Contraction". Principles of Meat Science (4th Edition).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|access date=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Farabee, M.J. "THE NERVOUS SYSTEM". Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ Jonathan, Cluett (2008). "Tendons". Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ^ Bridwell, Keith (06/07/2008). "Ligaments". Retrieved 2009-03-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "articular". Random House Unabridged Dictionary. Random House, Inc. 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

- ^ "neurologic". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-15.