Louis H. Carpenter

Louis Henry Carpenter | |

|---|---|

Brigadier General Louis H. Carpenter, 5th Cavalry | |

| Place of burial | Trinity Episcopal Church New Cemetery, Swedesboro, New Jersey |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1899 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Commands | 1st Division, 3rd Corps at Chickamauga in May 1898 3rd Division, 4th Corps at Tampa, Florida later in 1898 Military Governor of the providence of Puerto Principe, Cuba until July 1899. |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War

|

| Relations | James Edward Carpenter (brother) |

| Other work | writer and speaker |

Louis Henry Carpenter (February 11, 1839–January 21, 1916) was a United States Army brigadier general and Medal of Honor recipient. He began his military career in 1861, first as an enlisted soldier before being commissioned as an officer the following year. During the American Civil War, he participated in sixteen campaigns with the 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment. He received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Indian Wars while serving with the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry. He was noted several times for gallantry in official dispatches.

Louis Carpenter dropped out of college to enlist in the Union Army at the beginning of the American Civil War and fought in the Gettysburg Campaign at the Battle of Fairfield. By the end of the Civil War, he held the rank of brevet lieutenant colonel, but also received a commission to first lieutenant in the Regular United States Army.

After the Civil War and until his transfer back East in 1887, he served on the western frontier. He engaged many Native American tribes, dealt with many types of renegades and explored vast areas of uncharted territory from Texas to Arizona. During the Spanish-American War, he commanded an occupation force and became the first military governor of Puerto Principe, Cuba. After 38 continuous years of service to his country, he retired from the Army on October 19, 1899, as a brigadier general. After his retirement, he became a speaker and a writer.

Early life and family

Louis H. Carpenter was a direct descendant (great-great-great-grandson) of the notable immigrant Samuel Carpenter (November 4, 1649 Horsham, Sussex, England–April 10, 1714 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), who came to America in early 1683 by way of Barbados.[1]

The eldest son of eight children born to Edward Carpenter 2nd and Anna Maria (Mary) Howey, Carpenter was born in Glassboro, New Jersey. In 1843, his family moved to Philadelphia where they attended Trinity Episcopal Church in West Philadelphia.[n 1][2]

His younger brother, James Edward Carpenter, served in the Union army as a private in the Eighth Pennsylvania Cavalry and later was commissioned a second lieutenant. He later became a first lieutenant, captain then a brevet major of volunteers.[1]

Military service

American Civil War

In July 1861, during his junior year, Carpenter dropped out of Dickinson College and joined the "The Fighting Sixth" Cavalry Regiment.[3] He became a private in the Union Army which later became known as the Army of the Potomac. Carpenter was trained as an infantry soldier who was capable of riding a horse to the battlefield and as a mounted scout. As a "horse soldier", Carpenter and others like him had a steep learning curve that proved difficult and frustrating during the first year of the conflict. He participated in the Peninsula Campaign and chased the audacious Jeb Stuart's Cavalry that went completely around the Union Army (June 13–15 1862). This caused great psychological concerns to the Union cavalry commanders and men. The "horse soldiers" were a far second best compared to the dashing Confederate cavalry.[4]

Rapid expansion of the Union Cavalry in the East was chaotic. At the beginning of the War, officers were elected by the men or appointed politically. This resulted in many misguided and inept commanders. The tools and techniques of pre-war cavalry often seemed inadequate, resulting in a steep learning curve that was costly in men and supplies. Slowly out the chaos came the tactics and leaders who proved worthy of the challenge. Union "horse soldiers" became cavalry troopers under this tough regimen and proved adept, dismounted and mounted on horseback, with their carbines, pistols, sabers and confident under their battle-proven leaders.[5] After the Seven Days Battles (June 25 to July 1, 1862), Carpenter was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Regular Army, 6th U. S. Cavalry, on July 17, 1862, for meritorious actions and leadership.[1]

Gettysburg Campaign

The Gettysburg Campaign was a series of engagements before and after the Battle of Gettysburg. To better understand Carpenter's role within the military organization, the following brief is provided. For more details, see Gettysburg Union order of battle.[4]

- The Army of the Potomac was initially under Major General Joseph Hooker then under Major General George G. Meade on June 28, 1863.

- The Cavalry Corps was commanded by Major General Alfred Pleasonton, with divisions commanded by Brigadier Generals John Buford, David McM. Gregg, and H. Judson Kilpatrick.[4]

| Division | Brigade | Regiments and Others |

|---|---|---|

|

First Division:

| ||

| Reserve Brigade: |

6th Pennsylvania:

Maj James H. Haseltine

|

The following list is the 6th US Cavalry Regiment's documented battles and engagements of June and July 1863.[6]

- Beverly Ford, Virginia, June 9, at the Battle of Brandy Station. The 6th was under Buford's right wing.

- Benton's Mill, Virginia, June 17, an engagement near Middleburg.

- Middleburg, Virginia, June 21, at the Battle of Middleburg.

- Upperville, Virginia, June 21, at the Battle of Upperville

- Fairfield, Pennsylvania, July 3, at the Battle of Fairfield

- Williamsport, Maryland, July 6, an engagement.

- Funkstown, Maryland, July 7, a small engagement.

- Boonesboro, Maryland, July 8 and 9, at the Battle of Boonesboro.

- Funkstown, Maryland, July 10, at the Battle of Funkstown.

On June 9, 1863, opposing cavalry forces met at Brandy Station, near Culpeper, Virginia. The 9,500 Confederate cavalrymen under Major General J.E.B. Stuart were surprised at dawn by Major General Alfred Pleasonton's combined arms force of two cavalry divisions of some 8,000 cavalry troops (including the 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment and Carpenter with his Company H) and 3,000 infantry. Stuart barely repulsed the Union attack and required more time to reorganize and rearm. This inconclusive battle was the largest predominantly cavalry engagement of the war to that time. This battle proved for the first time that the Union horse soldiers, like Carpenter, were equal to their Southern counterparts.[7]

Battle of Fairfield

On July 3, 1863, reports of a slow moving Confederate wagon train in the vicinity of Fairfield, Pennsylvania, attracted the attention of newly commissioned Union Brigadier General Wesley Merritt of the Reserve Brigade, First Division, Cavalry Corps.[8] He ordered the 6th U.S. Cavalry under Major Samuel H. Starr to scout Fairfield and locate the wagons, resulting in the Battle of Fairfield.

Carpenter's next action was with Major Starr on July 3, 1863. Starr had his 400 troopers dismount in a field and an orchard on both sides of the road near Fairfield. Union troopers directed by their officers took up hasty defensive positions on this slight ridge. Carpenter's troops and others threw back a mounted charge of the 7th Virginia Cavalry, just as the Confederate Chew's Battery unlimbered and opened fire on the Federal cavalrymen. Supported by the 6th Virginia, the 7th Virginia charged again,[9] clearing Starr's force off the ridge and inflicting heavy losses. General "Grumble" Jones, outnumbering the Union forces by more than 2 to 1, pursued the retreating Federals for three miles to the Fairfield Gap, but was unable to eliminate his quarry. Major Starr who was wounded in the first attack was unable to escape and was captured. Small groups of the 6th Cavalry," ... reformed several miles from the field of action by Lt. Louis H. Carpenter," harassed the Virginia troopers giving the impression of the vanguard of a much larger force.[10]

Carpenter, in this fight with others of his small regiment at Fairfield, stood against two of the crack brigades of Stuart's cavalry. The 6th Cavalry's stand was considered one of the most gallant in its history and helped influence the outcome the battles being fought around Gettysburg. While the 6th Cavalry regiment was cut to pieces, it fought so well that its squadrons were regarded as the advance of a large body of troops. The senior officer of those brigades was later criticized severely for being delayed by such an inferior force. Had the 6th Cavalry regiment not made their stand, the two brigades of Virginians could have caused serious problems to the Union rear areas.[11]

Lieutenant Carpenter, of Troop H, was one of only three officers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry to escape from the deadly melee at Fairfield on July 3, 1863.[1] Private George Crawford Platt, later Sergeant, an Irish immigrant serving in Carpenter's Troop H, was awarded the Medal of Honor on July 12, 1895, for his actions that day at Fairfield. His citation reads, "Seized the regimental flag upon the death of the standard bearer in a hand-to-hand fight and prevented it from falling into the hands of the enemy." His "commander", as an eyewitness, documented Private Platt's "beyond the call of duty" behavior that day.[12] Carpenter was brevetted from lieutenant to lieutenant colonel for his gallant and meritorious conduct for his actions at Fairfield. During this time period, he was mentioned in official reports and dispatches.[1][13]

Overland Campaign

On April 5, 1864, Major General Philip Sheridan was appointed to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac under the newly promoted general-in-chief Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant.[14] Carpenter became his aide-de-camp similar to today's executive assistant.[1] It is unknown how much of an influence Carpenter had on Sheridan on the concept of deploying Union cavalry to become more effective and independent in roles such as long-range raids. Carpenter's treatise on "The Battle of Yellow Tavern" suggests that he had some influence on what was later called the Richmond or Sheridan's Raid.[15]

On May 8, 1864, at the beginning of the Overland Campaign, Sheridan went over his immediate superior, Major General Meade's head and told Grant that if his Cavalry Corps were let loose to operate as an independent unit, he could defeat Confederate Major General J.E.B. Stuart. "Jeb" Stuart was the most prominent and able cavalry officer of the south. Grant was intrigued and convinced Meade of the value of Sheridan's request.[14]

The May 1864 Battle of Yellow Tavern was the first of four major so called strategic raids. The others being the Trevilian in June 1864, the Wilson-Kautz in late June, and the First Deep Bottom in July 1864. Of all of these, only the Battle of Yellow Tavern can be considered a clear Union victory. The defeat and resulting death of "Jeb" Stuart made this clear during the first raid. At best, the follow-up raids diverted Confederate forces required to deal with them from where they were needed elsewhere.[16] Despite what Carpenter and other supporters of Sheridan have written, further raids of this caliber were less than successful. And these raids may have even hindered the Union effort by the lack of reconnaissance and intelligence Sheridan could have otherwise provided.[17] How long Carpenter served with Sheridan is not currently known. Carpenter is not mentioned in Sheridan's personal memoirs or other major books on Sheridan.[18]

In the 1865 Appomattox Campaign, it was Sheridan's cavalry, including Carpenter, that closed the final escape route that culminated in the surrender Confederate General Robert E. Lee and the symbolic end of the Civil War.[19]

End of the Civil War

Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Carpenter was promoted to first lieutenant in the Regular Army on September 28, 1864.[1] Through the course of the war, he served in 16 campaigns and most if not all of the 166 battles related to them from the 1861 Peninsula Campaign, the 1862 Maryland Campaign, Campaign at Fredericksburg, the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign, Chancellorsville (in Stoneman’s raid to the rear of Lee’s army), the 1864 The Wilderness and to the final 1865 Appomattox Campaign.[20][21]

After the fighting stopped and Reconstruction began, Carpenter went with the 6th Cavalry to Texas in October 1865. On November 29, 1865, the 6th Cavalry headquarters was established in Austin, Texas where it was part of the Fifth Military District that covered Texas and Louisiana under Generals Philip Sheridan and later under Winfield Scott Hancock.[22]

There was little or no fighting during the state of martial law imposed while the military closely supervised local government, enrolled freemen to vote, excluded former Confederate leaders for a period of time, supervised free elections, and tried to protect office holders and freedmen from violence. But Carpenter and his men did face a low level of civil hostility and violence during this uneasy transition period by trying to keep the peace.[23] In mid March 1866, Carpenter, was "mustered out" and reverted to his Regular Army rank of first lieutenant and returned home to Philadelphia on leave.[1]

Indian Wars and frontier service

10th Cavalry Regiment–The Buffalo Soldiers

After the Civil War, Carpenter was serving as a first lieutenant in the Regular U.S. Army and volunteered for cavalry duty with "Negro Troops" that were being raised.[1] The 10th U.S. Cavalry was formed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1866 as an all-African-American regiment. By the end of July 1867, eight companies of enlisted men had been recruited from the Departments of Missouri, Arkansas, and the Platte. Life at Leavenworth was not pleasant for the 10th Calvary. The fort's commander, who was openly opposed to African-Americans serving in the Regular Army, made life for the new troops difficult. Benjamin Grierson sought to have his regiment transferred, and subsequently received orders moving the regiment to Fort Riley, Kansas. This began on the morning of August 6, 1867 and was completed the next day in the afternoon of August 7.[24][25]

Carpenter accepted the rank of captain in the Regular Army on July 28, 1866 and took command of the African-American troops of "D" company, 10th U.S. Cavalry. The 10th U.S. Cavalry regiment was composed of black enlisted men and white officers, which was typical for that era. Carpenter was assigned to the newly formed Company H on July 21, 1867[n 2][25] and served with these original "Buffalo Soldiers" for thirteen years of near continuous conflict with the Native Americans in the southwest United States. He was dispatched to Philadelphia to recruit non-commissioned officers in late summer and fall of 1867.[n 3][25] His efforts contributed to the high level of veteran soldiers who became the core non-commissioned officers of the 10th Cavalry.[24]

Carpenter's men respected him, and his company had the lowest documented desertion rate of the Regular Army during his charge. He was known as being fair, firm, and consistent. He learned, saw and understood, the hardships and racial bigotry his men faced. After his service with the 10th, he campaigned and defended what his Buffalo Soldiers had done and could do. His ability to train and lead was notable and set a standard for cavalry units.[1]

Battle of Beecher Island

A soldier offers aid to his wounded comrade after the Battle of Beecher Island. The Harper's article states that this is "Bvt. Col. Louis H. Carpenter greeting Lt. Col. G. A. Forsyth" who was twice wounded by gunfire and who had fractured his leg when his horse fell. Notice officer shoulder boards.

On September 17, 1868, Lieutenant Colonel G. A. Forsyth with a mounted party of 48 white scouts, was attacked and "corralled" by a force of about 700 Native American Indians on a sand island up the North Fork of the Republican River; this action became the Battle of Beecher Island.[26] The Indians were primarily Cheyenne, supported by members of the Arapaho tribe under the Cheyenne War Chief Roman Nose, who was later killed in the battle.[26] Two of Forsyth's scouts broke through at night and rode frantically to get help and they were both able to reach Fort Wallace where rescue plans were quickly made.[27][28] Three rescue parties went out on different routes to find the endangered party due to the uncertainty of their location. The first was Carpenter commanding with his Troop H and Troop I under Captain Baldwin. Major Brisbin in command of two troops of the 2nd Cavalry took another route. Captain Bankhead, went with about 100 men of the 5th Infantry, took a third route.[28]

Carpenter’s troops were the first of the three commands to arrive on the battlefield. Over fifty dead horses greeted them with their putrid smell. Forsyth’s command had been out of rations and forced to survive on the decaying horse flesh. All of Forsyth's officers had been killed or wounded during the battle. Forsyth, who had been twice wounded by gunfire along with a fractured leg when his horse fell, was not expected to survive another day. The air around him was completely filled with a great stench and was swarming with black flies feasting on the defensive line of dead horses. The square sandy hole, where Forsyth was lying, was half encircled by dead horses and would have become his grave if help had not arrived when it did. Other gun pits, interconnected, contained the living and the dead of his unit.[28]

Carpenter immediately secured the area and pitched a number of tents up wind nearby. The wounded men were carefully carried there for more healthy air and the dead men and horses were buried to reduce the stench and possibility of disease. Twenty-six hours later, Captain Bankhead arrived, bringing with him the two troops of the 2nd Cavalry.[28]

Battle of Beaver Creek

On October 14, 1868, two weeks after Carpenter had returned to Fort Wallace with the survivors of Forsyth’s command, he was ordered out once again. Troops H and I of the 10th Cavalry sallied forth to escort Major Carr of the 5th Cavalry to his new command with supplies to Beaver Creek. Near there Carpenter's supply train and command was attacked by a force of about 500 Indians with no sign of the 5th Cavalry present.[27][26]

Carpenter, seeking a more defensive posture closer to Beaver Creek, advanced for a short period then circled the supply wagons in a defendable area. This was possible because his mounted troopers fought a mobile delaying action. On his command, Carpenter's men rushed inside at the gallop. They dismounted and took up a defensive firing line at the gap between the wagons they had just entered.[26]

On Carpenter's command, several massive volleys of aimed Spencer repeating rifles hit the front waves of the mounted Indians. The volleys decimated them as if hit by cannon filled with musket balls. A number of warriors, dismounted and using their ponies as bullet breaks, returned fire. Nearly all of these warriors died along with their ponies. Only three warriors made it to within fifty yards of the wagons before their demise. The Indians were so traumatized and demoralized by Carpenter's defense that they did not renew their attack.[26]

Carpenter's troopers then accomplished their primary task by sending out scouts to find the location of the 5th Calvary. This was done without further incident and they arrived back to Fort Wallace on October 21.[26]

Carpenter's command had traveled some 230 miles in a week, routed some 500 mounted Indians, delivered the needed supplies with the new commander of the 5th Cavalry and completed all as effectively and professionally as any other command could do. For their gallantry in this fight on Beaver Creek, the officers and men of the "Buffalo Soldiers" were thanked by General Sheridan in a general field order and in official dispatches to the War Department in Washington. Captain Carpenter was brevetted Colonel."[26] In 1898, for his efforts in September and October 1868, Carpenter became one of seven 10th Cavalry soldiers to be awarded the Medal of Honor during its service on the frontier.[27][26]

Defense of the Wichita I

The 10th Regimental headquarters remained at Fort Gibson until March 31, 1869, when they moved to Camp Wichita, Indian Territory (now the state of Oklahoma). They arrived on April 12, 1869. Camp Wichita was an old Indian village inhabited by the Wichita tribe on the Anadarko Reservation. General Sheridan had selected a site nearby for a military post and Carpenter with the rest of the 10th Cavalry was ordered there to establish and build it. Some time in the following month of August, the post was given the name of Fort Sill. Civil War Brigadier General Joshua W. Sill was a classmate and friend of Sheridan who was killed in action in 1862.[25]

On June 12, 1869, Camp Supply was attacked by a raiding party of Comanche intent on stealing cavalry mounts. The 3rd Infantry with Troops A & F of the 10th Cavalry pursued them, but were ambushed by the warriors. Carpenter with Troops H, I, & K flanked the Indians, forcing them to withdraw.[25]

On August 22 & 23, 1869, Carpenter and other troopers became involved in a fierce attack by Kiowa and Naconee Indians, who were focused on destroying the buildings and settlement on the Anadarko Reservation.[29] Carpenter, with Troops H and L, patrolled the area aggressively and engaged several groups of warriors, setting prairie fires upwind of the settlement at different points. Further and increasingly violent assaults were made by the Native Americans, in numbers ranging from 50 to 500 at different points of the defensive lines. The decisive feature of the engagement was a charge made by Captain Carpenter's troopers. His men routed a body of over 150 warriors, who were about to take up a commanding position in rear of other defenders. On June 5, 1872, the 10th left Fort Sill to elements of the 3rd Infantry and proceeded back to Fort Gibson.[25]

Satank, Satanta and Big Tree

In May 1871, Carpenter was involved in the capture and escort of the Kiowa warrior and medicine man Satank, along with the Kiowa War Chiefs Santana, and Big Tree at Fort Sill, Indian Territory, now in Oklahoma. General Sherman was present at the fort due to an inspection tour; also present was Colonel Benjamin Grierson.[29] These three Native American leaders were the first to be tried, for raids (Warren Wagon Train Raid) and murder, in a United States civil court instead of a military court. This would deny them any vestige of rights as prisoners of war by being tried as any common criminal in the Court of the Thirteenth Judicial District of Texas in Jacksboro, Texas near Fort Richardson.[30][31]

The military leaders at the fort had been given written information from the Indian Agent regarding the killings during the raid. Plans were made to arrest the Indians involved. D Troop was hidden on foot behind the main office building. Carpenter had mounted troopers waiting nearby. Sherman and Grierson sat on the porch, reviewing the situation and waiting for the Indians to arrive. When the Indians came, they blatantly boasted of what they had done. After Sherman told the Indians they were under arrest, a signal was given and the dismounted troopers came forward with carbines and pistols in hand. Lone Wolf, supporting the Kiowa Chiefs, pulled a rifle out from under his blanket serape and pointed it at Sherman. Sherman, ready for any problem, quickly disarmed him before the trigger could be pulled. Big Tree made an attempt to escape but was quickly subdued by Carpenter's mounted troopers. Sherman decided that these men were criminals to be tried in a civil court and Carpenter was told to get it done.[31]

Carpenter faced many problems associated with this, including the possibility of the Indians being rescued by their followers or being lynched by angry settlers, during their transport to the civilian court. During transport, Satank hid himself under his red blanket in his wagon while he gnawed the base of his thumb to the bone. This allowed him to slip the manacle from his wrist while he sang his death chant. With a small hidden knife that was not found during two separate searches, he stabbed the driver (who survived), both falling out of the wagon, grabbed a soldier's unloaded carbine and was mortally wounded in his escape attempt.[31][33]

The other two Kiowa were tried, found guilty, sentenced to death, had their sentences commuted to life and then paroled within a few years. They violated parole by raiding; Satanta was sent to the Huntsville State Penitentiary in Texas where, in despair, he later killed himself.[34] Big Tree, who presented witnesses to his non-involvement, was returned to the reservation and accepted pacification.[33] He lived on in the sadness of a warrior in exile. He later became a Christian and eventually, a minister in the Baptist church. The same Kiowa chief who had supervised the torture and burning of captives went about converting his own people to Christ. There were days, he would proudly recount his cruel acts against the white man, although it is faithfully recorded that he always concluded those tales with the solemn note that God had forgiven him for those "hideous" acts.[34]

Defense of the Wichita II

In August 1874, Carpenter became involved in fighting at Anadarko Reservation, Wichita, Indian Territory.[29] This fighting is considered the first of many clashes during the Red River War (1874-75). Carpenter, with Troops H & I was sent to support Fort Sill and by using aggressive patrols engaged several Kiowa and Comanche raiding parties. The relatively peaceful Wichita Indians on the reservation were targets of the hostile Indians because of their increasing positive status under pacification.[35] The 10th were sent to Fort Concho in Texas where they were established on April 17, 1875. The exception was Carpenter's troop stationed at Fort Davis as of May 1, 1875.[25]

Victorio Campaign and map making

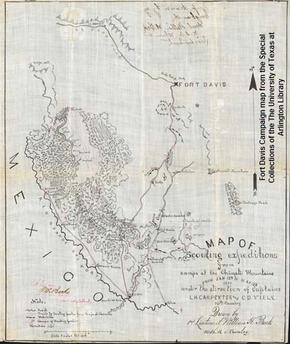

A hand drawn military map from the 1880 campaign against Victorio and his Chiricahua Apaches. Image from the Special Collections of The University of Texas at Arlington Library.

Carpenter became heavily involved in the Victorio Campaign of 1879–80.[29] Victorio was a warrior and chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apaches.[36] From January 12, 1880 to May 12, 1880, Carpenter directed scouting missions into the isolated Chinati Mountains bordering the United States with Mexico. The surrounding area on the American side was the high desert of far West Texas. This is where Victorio and other Apaches had been making raids. These scouts helped provide the first reliable maps drawn in the areas of operation.[n 4] Finding waterholes and mapping the area was a critical step in Victorio campaign.[37] On May 12, 1880, when eight Apache attacked a nearby wagon train. Captain Carpenter and H Company pursued the Apaches to the Rio Grande River. There, under orders, Carpenter had to stop at the international border with Mexico.[38]

Rattlesnake Springs

Colonel Grierson, commander of the 10th Cavalry, traversed the hot Chihuahuan Desert and then the narrow valleys of the Chinati Mountains, reaching Rattlesnake Springs on the morning of August 6, 1880. His cavalrymen and their mounts were worn down from the forced march of over 65 miles in 21 hours. After resting and getting water, Grierson carefully placed his men in ambush positions. Carpenter, with his two cavalry troops, arrived as reinforcements and were posted in reserve a short distance south of the spring. The cavalrymen settled down to wait as Indian scouts brushed away any sign of their presence.[38]

A little after two o'clock in the afternoon, Victorio and his Apaches slowly approached the springs. Victorio somehow sensed danger and halted his men. With the hostile Apaches in their sights appearing ready to bolt, the soldiers did not wait and opened fire on their own initiative; Victorio's men scattered and withdrew out of carbine range. Victorio's people needed water and believing that there were only a few soldiers present, regrouped and attacked immediately. As the battle progressed, Victorio sent his warriors to flank the soldiers. Carpenter charged forward with companies B and H and a few massed volleys from their carbines sent the hostiles scattering back up the canyon. Stunned by the presence of such a strong force but in desperate need of water, Victorio repeatedly charged the cavalrymen in attempts to reach the spring. Grierson's cavalry defenders, now bolstered by Carpenter's two companies, stood firm. The last such attempt to break the soldiers was conducted near nightfall and when it failed, Victorio and his followers withdrew into the westward into the mountains. Carpenter with his two companies remounted in pursuit until darkness halted the effort.[38]

On August 7, Carpenter, with Captain Nolan as second in command, and three companies of troopers headed out to Sulfur Springs to deny that source of water to the Apaches. In the early light of day, Victorio saw a string of wagons rounding a mountain spur to the southeast and about eight miles distant, crawling onto the plain. Victorio sent a band of warriors riding out of the mountains and attacked savagely. The wagons held a load of provisions for Fort Davis with a company of infantry riding in some of the wagons. The warriors were met with rifle fire, as the teamsters circled the wagons in defensive positions. Alerted by his Indian scouts, Carpenter and two companies charged to the rescue. The Apache attack disintegrated as the warriors fled in confusion to the southwest to rejoin Victorio's main force as it moved deeper into the Carrizo Mountains. Nolan's ambush was not ready and the scattered warriors were able to avoid them.[38]

Pursuit of Victorio

On August 9, fifteen Texas Rangers with their Indian scouts, located Victorio's main supply camp on Sierra Diablo. The Rangers joined Carpenter in the attack while Nolan guarded Sulfur Springs. Carpenter's attack scattered the Indian guards while the troopers secured 25 head of cattle, provisions and several pack animals. Victorio under increasing pressure, short of food and more importantly water, began to head south in two main groups. By August 11, Carpenter was on the trail in pursuit but, with horses tired and thirsty from the campaign, the chase was slow. Carpenter divided his command, with Nolan with his company and Texas Rangers on one route, while he took the rest of the command on another route. On August 13, Nolan reached the Rio Grande where Indian scouts reported that Victorio had crossed the border into Mexico the evening before. Carpenter arrived later and ordered the cavalrymen to rest near the river.[38]

On October 14, 1880, a sharpshooter of the Mexican Army ended Victorio's life at Cerro Tres Castillos, in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico.[39]

Over 34,420 miles of uncharted terrain were charted from 1875 to 1885 by Carpenter and other officers of the 10th Cavalry in West Texas. They added 300 plus miles of new roads with over 200 miles of telegraph lines. The scouting expeditions took the Buffalo soldiers through some of the harshest and desolate terrain ever documented in the American west. Excellent maps were provided by Carpenter and other officers showing the scarce water holes, mountain passes and grazing areas. These efforts by Carpenter and others of the 10th Cavalry were completed under adverse weather, limited supplies and the primitive equipment of the day. They had to be on the alert for the unexpected hit and run raids from Apaches and other Native American hostiles and bandits of all types."[37]

What type of officer was Louis H. Carpenter? The book "Frontier Cavalryman" provides the following quote[40]:

|

Forts and Commands

From August 30, 1878 to May 29, 1879, Carpenter, while holding the rank of captain in the Regular Army, but brevetted as a colonel in the 10th Cavalry, served as Commanding Officer of Fort Davis. Later, he served another period of command at the fort, between June 13 to July 27, 1879.[41] Carpenter was transferred to the 5th Cavalry with promotion to major, Regular Army, in March 1883. He then commanded the Army posts of Fort Robinson in Nebraska, Fort Sam Houston in Texas and Fort Myer in Virginia in late 1887.[1]

On July 4, 1888, on the battlefield of Gettysburg, Carpenter was "court-martialed" for being absent without leave the previous day. He proved that his absence was due to the Secretary of War who, unmindful of Carpenter's duties as a former member of the Sixth U.S. Cavalry in the Civil War, had neglected to issue orders to Carpenter in time to allow him to reach Fairfield for their 5th annual veteran's reunion.[n 5] Major Carpenter was on duty with a contingent of soldiers at the bequest of William Crowninshield Endicott, the Secretary of War, for the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg and its Blue & Gray reunions.[42]

Late career and Spanish-American War

Carpenter served as the first Director of the "Cavalry and Light Artillery School" at Fort Riley, Kansas as a lieutenant colonel, Regular Army, 7th Cavalry (1892–1897). This school "formed the basis for practical instruction that enabled the officers and men who participated to study the duties of the soldier in garrison, in camp, and on the march."[n 6] He also served as President of the Board to Revise Cavalry Tactics for the United States Army.[20]

In 1891, the United States Army conducted an experiment to integrate Indian soldiers into Regular Army units. While the primary object was to give employment, another was to utilize the talents of warriors from the most dangerous tribes. A significant number were sent to the "Cavalry School" at Fort Riley starting in late 1892. They received training not only in cavalry tactics, but in hygiene and classes in English. Unfortunately, probably by the lack of patience on part of the United States Army, and partly because of language difficulties and racial discrimination, the experiment failed and was discontinued in 1897. Carpenter had handpicked Lieutenant Hugh L. Scott to organize and command Troop L (composed of Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Indians) for the 7th Cavalry.[43] Scott commanded Troop L from inception to release of duty. Troop L, noted for their "deportment and discipline", was the last of these Native-American Troops to be disbanded soon after the "final review" of the Cavalry School's Director.[n 7][44] Carpenter was promoted to colonel, Regular Army, while stationed with the 5th Cavalry in 1897 and in May 1898, he was commissioned a brigadier general of volunteers for the duration of the Spanish-American War.[1]

General Carpenter commanded the 1st Division, 3rd Corps at Chickamauga and afterwards commanded the 3rd Division, 4th Corps at Tampa, Florida. Later, he was ordered to Cuba to occupy the Providence of Puerto Principe with a force consisting of the 8th Cavalry, 15th Infantry and the 3rd Georgia Volunteers. His were the first troops to take station in Cuba after the Battle of Santiago. Carpenter was appointed Military Governor of the province and remained in that capacity until July 1899.[45][21] Colonel Carpenter was promoted on October 19, 1899, to brigadier general, Regular Army; he then retired the next day, at his own request, having served honorably for 38 years.[1]

Retirement

After retiring from the Army Carpenter went home to Philadelphia but never married or had any children. He updated and completed the book his father Edward Carpenter started on his family's genealogical research, publishing it in 1912, regarding his immigrant ancestor Samuel Carpenter.[1]

He spent time writing about his Civil War service and his time on the Western Frontier. His work on the May 1864 Richmond Raid, also known as Sheridan’s raid, with the resulting Battle of Yellow Tavern where Confederate Army Major General J.E.B. Stuart was mortally wounded is still used as a basic reference. He gave many talks and wrote articles for the G.A.R. The Grand Army of the Republic was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army who had served in the American Civil War.[1]

Brigadier General Carpenter died on January 21, 1916, in Philadelphia and was buried in the family plot at Trinity Episcopal Church New Cemetery, Swedesboro, New Jersey.[1][46]

Honors and awards

During his military career, Carpenter earned the Medal of Honor during the Indian campaigns. He received a brevet promotion for bravery and was mentioned in dispatches during the Civil War. He received another brevet promotion and mention in military dispatches during the Indian campaigns.

Medal of Honor citation

Rank and organization: Captain, Company H, 10th U.S. Cavalry. Place and date: At Indian campaigns, Kansas and Colorado, September–October 1868. Entered service at: Philadelphia, Pa. Birth: Glassboro, N.J. Date of issue 8 April 1898.

Citation:

- Was gallant and meritorious throughout the campaigns, especially in the combat of October 15 and in the forced March on September 23, 24, and 25 to the relief of Forsyth’s Scouts, who were known to be in danger of annihilation by largely superior forces of Indians.[47]

Military promotions

- Private: July 1861

- Corporal: November 1, 1861

- Sergeant: late 1861 or early 1862[1]

| Brigadier general |

|---|

| O-7 |

| October 19, 1899[n 8] |

| Colonel | Lieutenant colonel | Major | Captain | First Lieutenant | 2nd lieutenant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-6 | O-5 | O-4 | O-3 | O-2 | O-1 |

|

|

|

|||

| 1897 | 1892 | March 12, 1883 | July 28, 1866 | September 28, 1864 | July 17, 1862 |

Brevet promotions

Carpenter received a brevet promotion to the ranks of major and lieutenant colonel during the Civil War, then Colonel during the Indian Wars.[n 9]

See also

Notes

- ^ Rivera, Edwin. "Then and Now Trinity Episcopal Church". Trinity Episcopal Church, West Philadelphia, is now where the Mario Lanza Park is located. The Church once stood west of Second Street, between Catharine and Queen streets. This Church was consecrated in 1822, closed in 1908 and razed by 1917 with the new park "Queen Park" open in late 1918. The park was renamed on September 29, 1967, in memory of Mario Lanza (1921–1959) one of Philadelphia's most beloved signers and film stars.

- ^ Bigelow, John, page 290. "Troop H.–(horse) Color, black. Organized July 21, 1867. Captain L. H. Carpenter; Lieutenants T. J. Spencer and L. H. Orleman."

- ^ Bigelow, John, "With a view to securing an intelligent set of men for the ranks the colonel had Captain Louis H. Carpenter, who was recruiting at Louisville, Kentucky, ordered to Philadelphia, Pa., to open a recruiting station there. Writing to Captain Carpenter, the colonel says, after referring to the captain's knowledge of Philadelphia: "I requested you to be sent there to recruit colored men sufficiently educated to fill the positions of noncommissioned officers, clerks and mechanics in the regiment. You will use the greatest care in your selection of recruits. Although sent to recruit men for the positions specified above, you will also enlist all superior men you can who will do credit to the regiment."

- ^ Goodwin, Katherine R. (Fall 2004). "Fort Davis Campaign Map Returns to Texas". The Compass Rose, Special Collections. University of Texas at Arlington Library. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Map of scouting expeditions from camps at the Chinati Mountains:] from Jan 12th to May 12 1880 under the direction of Captains L. H. Carpenter and C. D. Viele, 10th Cavalry, "The small, 16" x 13 ¼" manuscript map acquired by Special Collections details the period when the 10th Cavalry was stationed in Texas and engaged the band of the Apache Victorio. The map was drawn in 1880 by Lieutenant William H. Beck, Grierson’s aide-de-camp, and it was done under the direction of Captains Louis H. Carpenter and Charles Viele, officers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry. The purpose of the scouting expeditions during the period of January to May, 1880, (as depicted) on the map, was to locate the waterholes and crossings along the Rio Grande used by Victorio and his men and find a way to prevent the Apaches from exploiting these resources." Retrieved on July 14, 2009. - ^ Mueller, Heinrich G. Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Reunion of the Survivors of the Sixth U.S. Cavalry] - Tuesday, July 3, 1888, Fraternally submitted, by Heinrich G. Mueller, Secretary. No. 95 Pasture Street, Allegheny, Pa., July 6, 1888. "We charged on Major Louis Carpenter's (formerly of our regiment) command, and for the first time, an old officer of the gallant old Sixth was completely surprised, his command demoralized and routed, and the gallant old Major left on the field, a prisoner of war." Then, "He was promptly court-martialed for being absent without leave (on) July 3(rd) and I do not know what the sentence would have been, had he not clearly proven that his absence was due to the Secretary of War, who unmindful of his duty to an old soldier, had neglected to issue the proper order in time for the Major to reach Fairfield in time for the (5th annual) reunion." Retrieved on July 14, 2009.

- ^ Stubbs, Mary Lee. Page 20. "In 1887 Congress appropriated $200,000 for a school at Fort Riley, Kansas, to instruct enlisted men of cavalry and light artillery, but five years went by (1892) before the Cavalry and Light Artillery School was formally established. Once it opened its doors, however, complete regimental troops and batteries trained there, as did recruits before they joined a regiment. In the years that followed, the school changed names several times, in 1907, becoming the Mounted Service School; in 1919, the Cavalry School; on 1 November 1946, the Ground General School; and in 1950, the Army General School. The school was discontinued in May 1955."

- ^ Stubbs, Mary Lee. Page 23. "By 1890 the abatement of the Indian threat brought about the first reduction in cavalry since the Civil War. Troops L and M of all regiments were disbanded and the number of privates in each of the other companies was reduced to 44 (from a maximun of 100), in effect a reduction of about 50%." Page 24 - "The next year part of the cut was restored in an experiment that attempted to integrate Indian soldiers into Regular Army units. The primary object was to give employment to a considerable number of warriors from the most dangerous tribes. Troops L of the 1st through the 8th Cavalry were reactivated with Indian enlisted personnel drawn, as nearly as possible, from the area in which each regiment was serving. For example, Troop L, 1st Cavalry, in Montana was filled in a very short time by members of the Crow tribe. That fall (1891), the regimental commander (1st Cavalry) reported that the new troopers possessed all the characteristics and traits essential to good light cavalry. Nevertheless, due partly to the language barrier and partly to the general attitude that existed between the two races, the experiment failed and the last unit of this type, Troop L, 7th Cavalry, was disbanded in 1897."

- ^ General Carpenter held several ranks due to brevet or temporary promotions. The dates given here reflect the permanent Regular Army rank when awarded.

- ^ During the American Civil War, the Union Army used brevet promotions. Soldiers and officers could be brevetted to fill officer positions as a reward for gallantry or meritorious service. Typically, the brevetted officer would be given the insignia of the brevetted rank, but not the pay or formal authority. It was not unheard of for an officer to have several different ranks simultaneously, such as being a brevet major general of volunteers, an actual brigadier general of volunteers, a brevet lieutenant colonel in the Regular Army, and an actual Regular Army rank of captain (e.g. Ranald S. Mackenzie). The practice of brevetting disappeared from the (regular) U.S. military at the end of the 19th century; instead, honors were bestowed with a series of medals. However, a similar practice of frocking continues in all five branches of the U.S. armed forces.

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Edward Carpenter & his son, Gen. Louis H. Carpenter (1912). "Samuel Carpenter and his Descendants". Samuel Carpenter and his Descendants. J.B. Lippincott Company. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) Note: Carpenters' Encyclopedia of Carpenters 2009]] (DVD format) has updates and corrections to the 1912 book. Subject is RIN 4066. - ^ Rivera, Edwin (2006). ""Then and Now Trinity Episcopal Church"" (PDF). Temple University Urban Archives. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ 1st Sgt. Chuck Burke (1998-09-03). ""The Fighting Sixth" Cavalry Regiment". 1st Sgt. Chuck Burke. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Eicher, David J. (2001), The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-684-84944-5

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Longacre, Edward G. (2000), Lincoln's Cavalrymen, A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac, Stackpole Books, ISBN 0-8117-1049-1

- ^ Haskin, William L., Major, retired; Carter, William H., Captain, 6th U.S. Cavalry (1896). "The Army of the United States - Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief". Sixth Regiment of Cavalry. New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) This is part of the U.S. Army Center of Military History online. - ^ Symonds, Craig L. (2001), American Heritage History of the Battle of Gettysburg, Harper Collins, ISBN 0-06-019474-X Page 36

- ^ "The Gettysburg National Military Park Virtual Tour". The Story of the Battle of Gettysburg. National Parks Service. 2001. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Longacre, p. 236, indicates that the 6th Virginia conducted the second charge alone.

- ^ Jones, Jim (May 26, 2009), "Starr, Samuel H., Major, 6th Cavalry, letter dated February 17 1868 regarding former Major George C. Cram, from the "Post of Mount Pleasant, Tex."", Cross Sabers

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Carter, William H., Colonel (1851–1920?) (1989), From Yorktown to Santiago with the Sixth U. S. Cavalry (reprint ed.), State House Press, ISBN 0938349422, retrieved July 14, 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|isbn2=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)- Note: Lt. Col. Carter, who wrote this book in 1900, was commissioned a second lieutenant at West Point (Class of 1873) and served with the Sixth from 1874 until his retirement as a Major General in 1915. The 1989 book is a reprint. See item 3.

- ^ Platt, George C. (July 12, 1895). "George C. Platt 6th United States Cavalry, Troop "H"". George C. Platt. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ United States, War Department (1889). "The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies". Official Records. US Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b Morris, Roy, Jr. (1992), Sheridan: The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan, Crown Publishing, ISBN 0-517-58070-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kansas, State Historical Society (1894). "The Journal of the U.S. Cavalry Association". M 968 (June 30, 1894). Moundridge, McPherson, KS: U.S. Cavalry Association.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Mircrofilm reel number M 969 & M970 for additional articles by Louis H. Carpenter from 6/30/1894 to 7/17/1896. - ^ Rhea, Gordon C. (1997), The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern May 7–12, 1864, Louisiana State University Press, ISBN 0-8071-2136-3

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Wittenberg, Eric J. (2002), Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, Potomac Books, ISBN 1-57488-548-0

- ^ Sheridan, Philip Henry (2006), Personal Memoirs of P H Sheridan General United States Army, vol. 1, BiblioBazaar, ISBN 1-4264-1484-6

- ^ Foote, Shelby (1974), The Civil War: A Narrative, vol. 3: Red River to Appomattox, Random House, ISBN 0-394-74913-8

- ^ a b Edward Carpenter & his son, Gen. Louis H. Carpenter. "Louis H. Carpenter". Buffalo Soldiers Biographies. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ a b Wittenberg, Eric (The General) (2007-11-07). "Rantings of a Civil War Historian: The worldview of a Civil War historian, publisher, and practicing lawyer". Brig. Gen. Louis H. Carpenter, U. S. Cavalry. Eric Wittenberg. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ Rodenbough, Theophilus Francis, Bvt. Brigadier General, retired (1896). "The Army of the United States - Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief". Sixth Regiment of Cavalry. New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Foner, Eric (1988), Reconstruction: America's unfinished revolution, 1863-1877, Harper & Row, ISBN 0060937165 See chapters 6 & 7.

- ^ a b Schubert, Frank N. (2004), On the Trail of the Buffalo Soldier II: New and Revised Biographies of African Americans (1866-1917), Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0842050795

- ^ a b c d e f g Bigelow, John Jr, Lieutenant, U.S.A., R.Q.M. Tenth Cavalry (no date given but about 1890). ""The Tenth Regiment of Cavalry" from "The Army of the United States Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief"". United States Army. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Leckie, William H. (December 1999), The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0806112442 0806112441

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c Lawton. "Buffalo Soldiers — 10th Cavalry Medal of Honor Recipients". Buffalo Soldiers. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Carpenter, Louis Henry, Brig. Gen, retired (1912), Carpenter's Recollections: The Battle of Beecher Island, Kansas State Historical Society, retrieved August 1, 2009

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Letter written in 1912 from Carpenter to Mr. George Martin of the Kansas State Historical Society. - ^ a b c d Edward Carpenter & his son, Gen. Louis H. Carpenter (1912). "Part 2, Buffalo Soldiers — 10th Cavalry". Buffalo Soldiers — 10th Cavalry,. J.B. Lippincott Company. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Wharton, Clarence Ray (1873-1941) (1935), History of Texas, Dallas, Texas: Turner Company, OCLC: 2152691 & LCCN: 35013617, retrieved August 18, 2009

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Texas, State Library. "Satanta". Archives and Manuscripts. Texas State Library & Archives Commission. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ^ Van Ryzin, Robert R. (February 6, 1990). ""Which Indian Really Modeled?"". Numismatic News. Krause Publications, F+W Media, Inc.

{{cite web}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b Peery, Dan W. "Chronicles of Oklahoma". March 1935. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Boggs, Johnny, Spark on the Prairie Mooney, James (1898). [http://books.google.com/books? id=f9sRAAAAYAAJ&print. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 328–333.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); External link in|title=|title=(help); Unknown parameter|cad=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|sec=ignored (help); line feed character in|title=at position 32 (help) - ^ Cruse, Brett (January 10, 2001). "Red River War". Texas Beyond History. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaywaykla, James (1972). Eva Ball (ed.). In the Days of Victorio: Recollections of a Warm Springs Apache. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. LCCN 73-101103.

- ^ a b Lawton. "Buffalo Soldiers — 10th Cavalry History". Buffalo Soldiers. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Gott, Kendall D. (March 17, 2005). "In Search of an Elusive Enemy: The Victorio Campaign 1879-1880" (PDF). Golbal War of Terrorism. Paper 5. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press: 41–47. ISSN 2004016523. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Thrapp, Dan L. (1974). Victorio and the Mimbres Apaches. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1076-7.

- ^

Kinevan, Marcos E., Brigadier General, USAF, retired (1998). Frontier Cavalryman, Lieutenant John Bigelow with the Buffalo Soldiers in Texas. Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso. ISBN 0-87404-243-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ National Park Service. "Commanding Officers of Fort Davis,". Fort Davis National Historic Site. National Park Service. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Mueller, Heinrich G. (1888). "Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Reunion of the Survivors of the Sixth U. S. Cavalry". Retrieved July 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bell, William Gardner (2005). "Commanding Generals and Cheifs of Staff 1775-2005 - Scott, Hugh Lenox, Major General official biography". Center for Military History. CMH Online. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0–16–072376–0. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

{{cite journal}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Stubbs, Mary Lee (1969). "ARMOR-CAVALRY - Part I: Regular Army and Army Reserve". Center for Military History. Army Lineage Series. Washington, D. C.: Office of the Chief of Military History: 22. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 69-60002

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Yates, Austin A., Major (1910). ""Schenectady County, New York: Its History to the Close of the Nineteenth Century"". Chapter XXVI (pp. 404–409). New York: Schenectady County, New York: 404–409. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Louis H. Carpenter at Find a Grave Retrieved on 2009-07-04

- ^ "U.S. Army Center of Military History Medal of Honor Citations Archive". American Medal of Honor recipients for the Indian Wars. June 8, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher Army Medal of Honor website" ignored (help)

Further reading

- Brady, Cyrus Townsend (1971) [1904]. Indian Fights and Fighters. Bison Books. ISBN 9780803257436.

- Heitman, Francis B. (1994) [1903]. Historical Register and Dictionary of US Army, 1789–1903, Volume 1 & 2. US Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780806314013.

- Longacre, Edward G. (1986). The Cavalry at Gettysburg. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7941-8.

- United States Senate, Veterans' Affairs of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare US Senate 1968 (1968). Medal of Honor 1863–1968. US Govt Printing Office.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|ocm=ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Wittenberg, Eric J. (1998). Gettysburg's Forgotten Cavalry Actions. Thomas Publications. ISBN 1-57747-035-4.

External links

- Introduction to Civil War Cavalry

- Platt MOH webpage

- Alice Kirk Grierson and the Tenth Cavalry Officers' Wives at Fort Davis

- Carpenter, Louis H., Cavalry Fighting Dismounted, November 1888 issue of Journal of the U.S. Cavalry Association cited by J. David Petruzzi in Hoofbeats and Cold Steel. Retrieved August 9, 2009. More articles by Carpenter at: Kansas State Historical Society, Mircrofilm reel numbers M 968, M 969 & M970. See item: The Journal of the U.S. Cavalry Association published in Moundridge, McPherson, KS.

- 1839 births

- 1916 deaths

- Army Medal of Honor recipients

- Union Army soldiers

- Union Army officers

- United States Army soldiers

- United States Army officers

- American military personnel of the Indian Wars

- American military personnel of the Spanish-American War

- Cavalry commanders

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War

- Texas-Indian Wars

- American writers