Mormon corridor

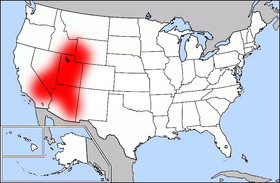

The Mormon Corridor is a term for the areas of Western North America that were settled between 1850 and approximately 1890 by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who are commonly known as Mormons.[1]

In academic literature, the area is also commonly called the "Mormon culture region."[2][3] It has also been referred to as the "Book of Mormon belt" as a cultural reference to the Bible Belt of the southeastern United States, and the Book of Mormon.

Location

Beginning in Utah, the corridor extends northward through western Wyoming and eastern Idaho to Yellowstone National Park and reaches south to San Bernardino, California on the west and through Mesa, Arizona on the east, extending to the U.S.-Mexico border. Settlements in Utah south of the Wasatch Front stretched from St. George in the southwest to Nephi in the northeast and including the Sevier River valley, the corridor is roughly congruent with the area between present-day Interstate 15 and U.S. Route 89. Most of the population of the state that is not along the Wasatch Front or in Utah's Cache Valley resides in this corridor. Outside the Western United States, more isolated Mormon settlements were also founded in Western Canada and Mexico.

History

The larger chain of Mormon settlements, ranging from Canada to Mexico, were initially established as agricultural centers or to gain access to metals and other materials needed by the expanding Mormon population. The communities also served as waystations for migration and trade centered on Salt Lake City during the mid- to late 19th century.

Communities in the generally fertile but relatively dry valleys of the Great Basin, Southeastern Idaho, Nevada and Arizona were dependent on water supplies. Irrigation systems, including wells, dams, canals, headgates, and ditches, were one of the first projects for a new community. Road access to timber in the mountains and pasturage for stock were important, as were carefully tended crops, gardens and orchards.

Initial Settlements

Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, personally supervised the founding of many outlying communities. Exploring parties were sent out to find settlement sites, and to identify sources of appropriate minerals, timber, and water. Western historian Leonard Arrington asserts that within ten years of the LDS arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, “…nearly 100 colonies had been planted; by 1867, more than 200; and by the time of (Brigham Young’s) death in 1877, nearly 400 colonies.” [1] These colonies had four distinct purposes: "...first, settlements intended to be temporary places of gathering and recruitment, such as Carson Valley in Nevada; second, colonies to serve as centers for production, such as iron at Cedar City, cotton at St. George, cattle in Cache Valley, and sheep in Spanish Fork, all in Utah; third, colonies to serve as centers for proselytizing and assisting Indians, as at Harmony in southern Utah, Las Vegas in southern Nevada, Lemhi in northern Idaho, and present-day Moab in eastern Utah; fourth, permanent colonies in Utah and nearby states and territories to provide homes and farms for the hundreds of new immigrants arriving each summer." [2]

At times, Young or his agents met incoming wagon trains of Mormon Pioneers, assigning the groups a secondary destination to establish a new community. After a relatively brief rest in the growing communities of the Salt Lake Valley, the groups would restock needed supplies and materials, gather livestock, and travel on. In addition, new colonizeers could be called from the pulpit. Young read the names of men and their families who were "called" to move to outlying regions. These "missions" for church members often lasted for years, as the families were to remain in their assigned area until released from the calling or given a new assignment. Colonizers traveled at their own expense and success depended on appropriate supplies and personal resourcefulness, as well as uncontrolled variables such as water supplies and weather.

Several of these colonies could also have provided support for a second migration of the Latter-day Saints which might have become necessary due to pressure by the U.S. government, starting with the Utah War. Some settlements were associated with existing or prior towns, and many were abandoned once the threat of persecution decreased after the 1890 Manifesto, and the transportation system in the Western United States matured. The First Transcontinental Railroad was especially significant in reinforcing or altering settlement patterns.

After Young's death in 1877, successive leaders of the LDS Church continued to establish new settlements in outlying areas of the west. The Salt River Valley in western Wyoming, now known as Star Valley was designated for settlement in August 1878, while Bunkerville and Mesquite, Nevada were settled in 1879 and 1880 respectively. (Allen, James B. and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, UT, 1976, p. 385) Communities were also established in eastern and southeastern Utah and western Colorado, primarily populated by LDS converts from the southern United States. Historians James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard estimate that at least 120 new LDS based settlements were founded between 1876 and 1879. (ibid., p. 385)

Settlements due to opposition to polygamy

Mounting legislation and prosecution of polygamists within the LDS community led to additional expansion. By 1884, LDS President John Taylor encouraged groups of church members in Arizona and New Mexico to cross the border into Mexico to establish communities. By the end of 1885, however, the Mormon colonists had been denied the opportunity to purchase land within the Mexican state of Chihuahua by the acting governor. While the colonists remained on rented land, negotiations between members of the LDS Quorum of Twelve Apostles and Mexican President Porfirio Diaz were successful and legal barriers were lifted. (Allen and Leonard, p. 386) In March 1886, the LDS community of Colonia Juarez was formally established. This settlement was shortly followed by two additional communities, Colonia Dublan and Colonia Diaz.

"Jell-O Belt"

The region has also been identified as the "Jell-O Belt",[4][5][6] referring to the 20th century Mormon cultural stereotype that Mormons have an affection for Jell-O (a gelatin-based food). In support of this image, Jell-O was designated Utah's official state snack food in 2001.[7] When drafting the resolution, the Utah Legislature gave many reasons to recognize Jell-O,[8] including that Utah had been the highest per capita consumer of Jell-O for many years, and how citizens of Utah had rallied to "Take Back the Title" after Des Moines, Iowa exceeded Utah in Jell-O consumption in 1999. The culture of Utah, petitions by Utahns, and campaigning by students of Brigham Young University were also mentioned as reasons for recognizing Jell-O.

See also

References

- ^ Origin of the term from a part of the National Park Service's "The Old Mormon Fort: Birthplace of Las Vegas, Nevada"

- ^ The Current State of the Mormon Culture Region This reference also includes a map, by county of Leading Church Bodies from 2000

- ^ Transformation of the Mormon Culture Region by Ethan R. Yorgason, University of Illinois Press (Selected text)

- ^ Washington Post

- ^ Films about Latter-day Saints

- ^ Crump, Steve. " Don't ask me. Getting jiggly outside the Jell-O Belt." The Twin Falls Idaho Times-News. March 21, 2004, p. B01.

- ^ BBC: "Utah loves Jell-O - official"

- ^ Utah Legislature, Resolution Urging Jell-O Recognition, 2001 General Session, State of Utah, Sponsor: Leonard M. Blackham

External links

- Map Gallery of Religion in the United States from American Ethnic Geography

- Latter Day Saint art and culture

- Regions within the American West

- Settlements in Utah

- Utah culture

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Idaho

- Latter Day Saint movement in Arizona

- Latter Day Saint movement in Nevada

- Latter Day Saint movement in California