Henry Hudson

Henry Hud | |

|---|---|

While no portraits of Hudson are known to exist, the Cyclopedia of Universal History offers this popular image to be of the navigator. | |

| Born | |

| Died | 1611, likely[1] |

| Occupation(s) | Dutch Sea Commander, former English Sea Commander, Author |

Henry Hudson (d. ca. 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator in the early 17th century. After several voyages on behalf of English merchants to explore a prospective Northeast Passage to India, Hudson explored the region around modern New York City while looking for a western route to the Orient under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company. He explored the Hudson River – the first European to see the river was Giovanni da Verrazano for the king of France Francis I in 1524 – and laid the foundation for Dutch colonization of the region.

Hudson's final expedition ranged further north in search of the Northwest Passage, to the Orient, leading to his discovery of the Hudson Strait and Hudson Bay. After wintering in the James Bay, Hudson tried to press on with his voyage in the spring of 1611, but his crew mutinied and they cast him adrift.[1] His ultimate fate is unknown.

Life and career

Hudson may have been born in London, England. Little is known of his early life. He is thought to have spent many years at sea, beginning as a cabin boy and gradually working his way up to ship's captain.

1607

In 1607, the Muscovy Company of the Kingdom of England hired Hudson to find the Northeast Passage to the Pacific coast of Asia. It was thought at the time that, because the sun shone for three months in the northern latitudes in the summer, the ice would melt and a ship could travel across the top of the world to the Spice Islands. The English were battling the Dutch for Northeast Passage routes.

Hudson sailed on the 1st of May with a crew of ten men and a boy on the 80-ton Hopewell.[2] They reached the east coast of Greenland on June 13, coasting it until the 22nd. Here they named a headland Young's Cape, a "very high mount, like a round castle" near it Mount of God's Mercy, and land at 73° N Hold-with-Hope. On the 27th they sighted "Newland" (i.e Spitsbergen), near the mouth of the great bay Hudson later simply named the Great Indraught (Isfjorden). On July 13 Hudson and his crew thought they had sailed as far north as 80° 23' N,[3] but more likely only reached 79° 23' N. The following day they entered what Hudson later in the voyage would name Whales Bay (Krossfjorden and Kongsfjorden), naming its northwestern point Collins Cape (Kapp Mitra) after his boatswain, William Collins. They sailed north the following two days. On the 16th they reached as far north as Hakluyt's Headland (which Thomas Edge claims Hudson named on this voyage) at 79° 49' N, thinking they saw the land continue to 82° N (Svalbard's northernmost point is 80° 49' N) when really it treaded to the east. Ice being packed along the north coast they were forced to turn back south. Hudson wanted to make his return "by the north of Greenland to Davis his Streights, and so for Kingdom of England," but ice conditions would have made this impossible. The expedition returned to Tilberry Hope on the Thames on September 15.

According to Thomas Edge, "William [sic] Hudson" in 1608 discovered an island at 71° N and named it Hudson's Touches (or Tutches).[4] However, he only could have come across it in 1607 (if he had made an illogical detour) and made no mention of it in his journal.[5] There is also no cartographical proof of this supposed discovery.[6] Also, Jonas Poole and Robert Fotherby both had possession of Hudson's journal while searching for his elusive Hold-with-Hope (on the east coast of Greenland) in 1611 and 1615, respectively, but neither had any knowledge of his (later) alleged discovery of Jan Mayen, sheding further doubt on him having discovered the island. The latter actually found Jan Mayen, thinking it a new discovery and naming it Sire Tommy Smith's Island.[7]

It has also been claimed by many authors[8] that it was the discovery of large numbers of whales in Spitsbergen waters by Hudson during this voyage that led to several nations sending whaling expeditions to the islands. While he did indeed report seeing many whales, it wasn't his reports that led to the trade, but that by Jonas Poole in 1610 which led to the establishment of English whaling and the successful voyage of Nicholas Woodcock in 1612 that led to the establishment of Dutch, French, and Spanish whaling.[9]

1608 to 1609

In 1608, Hudson made a second attempt, trying to go across the top of Russia. He made it to Novaya Zemlya but was forced to turn back.

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by the Dutch East India Company to find an easterly passage to Asia. He was told to sail around the Arctic Ocean north of Russia, into the Pacific and so to the Far East. Hudson could not complete his intended route due to the ice that had plagued his previous voyages, and those of many others before him. On September 6, 1609 John Colman of his crew was killed by Native Americans with arrow to his neck.[10] On September 11, 1609 he sailed into what is now New York City.[11] The following day Hudson began his first ride up what is now known as the Hudson River. [12]

Having heard rumors by way of Jamestown and John Smith, he and his crew decided to try to seek out a Southwest Passage through North America. In fact, no Northwest Passage to the Pacific existed north of the Strait of Magellan and south of the Arctic until one was created by the construction of the Panama Canal between 1903 and 1914. The Native Americans, who relayed the information to John Smith, were likely referring to what are known today as the Great Lakes.

Along the way, Hudson traded with several native tribes, obtaining shells, beads and furs. His voyage established Dutch claims to the region and the fur trade that prospered there. New Amsterdam in Manhattan became the capital of New Netherland in 1625. On his return trip to Amsterdam, he stopped in Dartmouth, Kingdom of England and was detained by authorities there, who wanted access to his log. He managed to pass the log to the Dutch ambassador to the Kingdom of England who sent it, along with his report, to Amsterdam.[13]

1610-1611

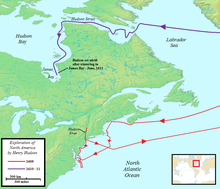

In 1610, Hudson managed to get backing for yet another voyage, this time under the English flag. The funding came from the Virginia Company and the British East India Company. At the helm of his new ship, the Discovery, he stayed to the north (some claim he deliberately stayed too far south on his Dutch-funded voyage), reaching Iceland on May 11, the south of Greenland on June 4, and then rounding the southern tip of Greenland.

Excitement was very high due to the expectation that the ship had finally found the Northwest Passage through the continent. On June 25, the explorers reached the Hudson Strait at the northern tip of Labrador. Following the southern coast of the strait on August 2, the ship entered Hudson Bay. Hudson spent the following months mapping and exploring its eastern shores. In November however, the ship became trapped in the ice in James Bay, and the crew moved ashore for the winter.

Mutiny

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

When the ice cleared in the spring of 1611, Hudson planned to continue exploring but his crew wanted to return home. Matters came to a head and the crew mutinied in June 1611. According to the mutineers, they set Hudson, his teenage son John, and eight crewmen - either sick and infirm, or loyal to Hudson - adrift in a small open boat, effectively marooning them. According to Abacuk Pricket's journal, the castaways were provided with powder and shot, some pikes, an iron pot, some meal, and other miscellaneous items, as well as clothing. However Prickett knew he and the other mutineers would be tried in England. The small boat kept pace with the Discovery for some time as the abandoned men rowed towards her but eventually Discovery's sails were let loose. Hudson was never seen again and his fate is not known. However, speculation that the crew killed Hudson has occurred.[1]

Only eight of the thirteen mutinous crewmen survived to return to Europe, and although arrested, none was ever punished for the mutiny and Hudson's (presumably resulting) death. One theory holds that they were considered valuable as sources of information, having travelled to the New World.[14] Perhaps for this reason they were charged with murder, of which they were acquitted, rather than mutiny, for which they most certainly would have been convicted and executed.

Legacy

The Hudson River in New York and New Jersey, explored by Hudson, is named for him, as are Hudson County, New Jersey, and Hudson, New York. In the Canadian Arctic, Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait, also discovered by Hudson, are named for him. He also appears as a mythic character in the famous story of Rip Van Winkle by Washington Irving.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c [1][dead link]

- ^ The following paragraph relies on Asher (1860), pp. 1-22; and Conway (1906), pp. 23-30.

- ^ Observations made during this voyage were often wrong, sometimes greatly so. See Conway (1906).

- ^ Purchas (1625), p. 11.

- ^ "The above relation by Thomas Edge is obviously incorrect. Hudson's Christian name is wrongly given, and the year in which he visited the north coast of Spitsbergen was 1607, not 1608. Moreover, Hudson himself has given an account of the voyage and makes absolutely no mention of Hudson's Tutches. It would have been hardly possible indeed for him to visit Jan Mayen on his way home from Bear Island to the Thames." Wordie (1922), p. 182.

- ^ Hacquebord (2004), p.229.

- ^ Purchas (1625), pp. 35-36 and pp. 83-88.

- ^ Many uncritical authors have blindly stated the above. Among them are Sandler (2008), p. 407; Umbreit (2005), p. 1; Shorto (2004), p. 21; Mulvaney (2001), p. 38; Davis et al. (1997), p. 31; Francis (1990), p. 30; Rudmose-Brown (1920), p. 312; Chisholm (Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911), p. 942; among many others.

- ^ See Poole's commission from the Muscovy Company in Purchas (1625), p. 24. For Woodcock see Conway (1906), p. 53, among others.

- ^ "New York's Coldest Case: A Murder 400 Years Old". New York Times. September 4, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Nevius, Michelle and James, "New York's many 9/11 anniversaries: the Staten Island Peace Conference", Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - Juet-modified-footer.rtf" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ Shorto 2004, pg.31

- ^ "Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Biographi.ca. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

References

- Asher, Georg Michael (1860). Henry Hudson the Navigator. Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, 27. ISBN 1402195583.

- Conway, William Martin (1906). No Man's Land: A History of Spitsbergen from Its Discovery in 1596 to the Beginning of the Scientific Exploration of the Country. Cambridge, At the University Press.

- Hacquebord, Lawrens. (2004). The Jan Mayen Whaling Industry. Its Exploitation of the Greenland Right Whale and its Impact on the Marine Ecosystem. In: S. Skreslet (ed.), Jan Mayen in Scientific Focus. Amsterdam, Kluwer Academic Publishers. 229-238.

- Purchas, S. 1625. Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes: Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells by Englishmen and others. Volumes XIII and XIV (Reprint 1906 J. Maclehose and sons).

- Shorto, Russell (2004), The Island at the Center of the World, Vintage Books, ISBN 1-4000-7867-9

- Wordie, J.M. (1922) "Jan Mayen Island", The Geographical Journal Vol 59 (3).

- Mancall, Peter C. (2009), Fatal Journey: The Final Expedition of Henry Hudson, Basic Books

External links

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- Henry Hudson - A Brief Statement Of His Aims And His Achievements by Thomas Allibone Janvier, at Project Gutenberg

- Hudson and the river named for him

- Henry Hudson biography page

- Henry Hudson at US-History.com

- Henry Hudson at Find a Grave

- A Map and Timeline of Hudson's 1609 voyage of discovery.

- Website of a Henry Hudson historical impersonator.

- [2] The Museum of the City of New York's Celebration of the 400th anniversary of Hudson's sailing into New York harbor, "The Worlds of Henry Hudson"

- Watch The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson at the National Film Board of Canada website

- A Journal of Mr. Hudson's last Voyage for the Discovery of a North-west Passage ; Abacuck Pricket ; Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca ; OCLC 17312467

- Excerpt from A Larger Discourse of the Same Voyage, by Abacuk Pricket, 1625