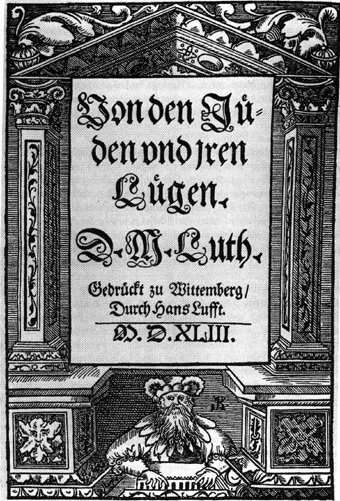

On the Jews and Their Lies

Martin Luther's anti-Jewish rhetoric and doctrines are often described as "anti-Semitism" [1] or "anti-Judaism." [2] Luther expected that presenting his understanding of the Christian gospel to the Jews would convert them, but when his efforts to persuade them to abandon the faith of their fathers with what he saw as "Christian love" failed, he became embittered and recommended harsh persecution of the Jews. Four centuries later, the Nazis cited his pamphlet On the Jews and Their Lies (1543) to justify their attempts at genocide. Since the 1980s, Lutheran church bodies and organizations have begun a process of formally disassociating themselves from these writings.

Luther's statements about the Jews

Luther's first known comment on the Jews is in a letter written to Reverend Spalatin in 1514 he stated:

I have come to the conclusion that the Jews will always curse and blaspheme God and his King Christ, as all the prophets have predicted....For they are thus given over by the wrath of God to reprobation, that they may become incorrigible, as Ecclesiastes says, for every one who is incorrigible is rendered worse rather than better by correction.[3]

"In his Letters to Spalatin, we can already see that Luther's hatred of Jews, best seen in this 1543 letter On the Jews and Their Lies, was not some affectation of old age, but was present very early on. Luther expected Jews to convert to his purified Christianity. When they did not, he turned violently against them." [4]

In 1519, Luther challenged the doctrine "Servitus Judaeorum" ("Servitude of the Jews"), established in Corpus Juris Civilis by Justinian I in 529. He wrote: "Absurd theologians defend hatred for the Jews. ... What Jew would consent to entrer our ranks when he sees the cruelty and enmity we wreak on them—that in our behavior towards them we less resemble Christians than beasts?"[5]

In his 1523 essay That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew, Luther distinguished between the religious yet emphasises the racial aspects of the Jews telling his followers that

"When we are inclined to boast of our position [as Christians] we should remember that we are but Gentiles, while the Jews are of the lineage of Christ. We are aliens and in-laws; they are blood relatives, cousins, and brothers of our Lord. Therefore, if one is to boast of flesh and blood the Jews are actually nearer to Christ than we are."

In August 1536, Luther's prince, Elector John Frederick of Saxony, issued a mandate that prohibited Jews from inhabiting, engaging in business in, or passing through his realm[6].

On the Jews and Their Lies

In his 1543 book On the Jews and Their Lies, Luther goes further than the widespread sentiments of his times. He states: "There is one thing about which they boast and pride themselves beyond measure, and that is their descent from the foremost people on earth, from Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob, and from the twelve patriarchs, and thus from the holy people of Israel." Luther uses Jewish internal quarrels to incite hatred against all Jews when he quotes the words of Jesus in Matthew 12:34, where Jesus called the Jewish religious leaders (Pharisees) of his day "a brood of vipers and children of the devil", and attributes this characteristic to all Jews. In the book, written three years before his death, Luther describes the Jews as (among other things) "miserable, blind, and senseless", "truly stupid fools", "thieves and robbers", "lazy rogues", "daily murderers", and "vermin", likens them to "gangrene", and recommends that Jewish synagogues and schools be burned, their homes destroyed, their writings be confiscated, their rabbis be forbidden to teach, their travel be restricted, that lending money be outlawed for them and that they be forced to earn their wages in farming. Luther advised "[i]f we wish to wash our hands of the Jews' blasphemy and not share in their guilt, we have to part company with them. They must be driven from our country" and "we must drive them out like mad dogs."

Finally, he wrote:

There is no other explanation for this than the one cited earlier from Moses — namely, that God has struck [the Jews] with "madness and blindness and confusion of mind." So we are even at fault in not avenging all this innocent blood of our Lord and of the Christians which they shed for three hundred years after the destruction of Jerusalem, and the blood of the children they have shed since then (which still shines forth from their eyes and their skin). We are at fault in not slaying them. Rather we allow them to live freely in our midst despite all their murdering, cursing, blaspheming, lying, and defaming; we protect and shield their synagogues, houses, life, and property. In this way we make them lazy and secure and encourage them to fleece us boldly of our money and goods, as well as to mock and deride us, with a view to finally overcoming us, killing us all for such a great sin, and robbing us of all our property (as they daily pray and hope). Now tell me whether they do not have every reason to be the enemies of us accursed Goyim, to curse us and to strive for our final, complete, and eternal ruin!" [7]

Luther advocated an eight-point plan to get rid of the Jews as a distinct group either by religious conversion or by expulsion:

- "First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them. ..."

- "Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed. ..."

- "Third, I advise that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, in which such idolatry, lies, cursing and blasphemy are taught, be taken from them. ..."

- "Fourth, I advise that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb. ..."

- "Fifth, I advise that safe-conduct on the highways be abolished completely for the Jews. ..."

- "Sixth, I advise that usury be prohibited to them, and that all cash and treasure of silver and gold be taken from them. ... Such money should now be used in ... the following [way]... Whenever a Jew is sincerely converted, he should be handed [a certain amount]..."

- "Seventh, I commend putting a flail, an ax, a hoe, a spade, a distaff, or a spindle into the hands of young, strong Jews and Jewesses and letting them earn their bread in the sweat of their brow... For it is not fitting that they should let us accursed Goyim toil in the sweat of our faces while they, the holy people, idle away their time behind the stove, feasting and farting, and on top of all, boasting blasphemously of their lordship over the Christians by means of our sweat. No, one should toss out these lazy rogues by the seat of their pants."

- "If we wish to wash our hands of the Jews' blasphemy and not share in their guilt, we have to part company with them. They must be driven from our country" and "we must drive them out like mad dogs."[8]

Schem Hamephoras and Luther's final sermon

Several months after publishing On the Jews and Their Lies, Luther wrote another attack on Jews titled Schem Hamephoras, in which he explicitly equated Jews with the Devil.[9]

In his final sermon shortly before his death, Luther preached "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord" [10].

The influence of Luther's views

16th Century reactions to Luther's words

Luther and the Jews, 1600-1900

The Nazi era

Luther's sentiments were echoed in the Germany of the 1930s. According to Daniel Goldhagen

One leading Protestant churchman, Bishop Martin Sasse published a compendium of Martin Luther's antisemitic vitriol shortly after Kristallnacht's orgy of anti-Jewish violence. In the foreword to the volume, he applauded the burning of the synagogues and the coincidence of the day: On November 10, 1938, on Luther's birthday, the synagogues are burning in Germany. The German people, he urged, ought to heed these words of the greatest antisemite of his time, the warner of his people against the Jews.

It was Luther's expression "The Jews are our misfortune" that centuries later would be repeated by Heinrich von Treitschke and appear as motto on the front page of Julius Streicher's Der Sturmer.

Dr. Robert Michael argues that Luther scholars who defend, censor, or try to tone down his views on the Jews, ignore the murderous implications of Luther's antisemitism. Like the Nazis, Luther mythologized the Jews as completely evil: they should not be treated as humans and should be cast out of Germany. They could be saved if they converted to Christianity, but their demonic hostility to Christian society makes this inconceivable. There was a strong parallel between Luther's ideas and feelings about Jews and Judaism and the essentially anti-Jewish Weltanschauung of most German Lutherans throughout the Holocaust.[11]

Luther's words and scholarship

Anglican Luther scholar Gordon Rupp wrote:

"Luther's antagonism to the Jews was poles apart from the Nazi doctrine of "Race". It was based on medieval Catholic anti-semitism towards the people who crucified the Redeemer, turned their back on the way of Life, and whose very existence in the midst of a Christian society was considered a reproach and blasphemy. Luther is a small chapter in th large volume of Christian inhumanities toward the Jewish people." [12]

and

"Needless to say, there is no trace of such a relation between Luther and Hitler. I suppose Hitler never once read a page by Luther. The fact that he and other Nazis claimed Luther on their side proves no more than the fact that they also numbered Almighty God among their supporters. Hitler mentions Luther once in Mein Kampf in a harmless context." [13]

"On the Jews and Their Lies goes beyond theological anti-Judaism; it calls for state-sponsored violence against the Jews; and therefore it contributed to a historical climate of German opinion in which genocide was conceivable." [14]

On the Jews and their Lies has been described as "a notorious Antisemitic document" by Humanitas-International.org; [15] according to Paul Johnson, it "may be termed the first work of modern anti-Semitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust." [16]

According to Diarmaid MacCulloch, "Luther's writing of 1543 is a blueprint for the Nazi's Kristallnacht of 1938"[17].

In his book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William L. Shirer wrote:

"It is difficult to understand the behavior of most German Protestants in the first Nazi years unless one is aware of two things: their history and the influence of Martin Luther. The great founder of Protestantism was both a passionate anti-Semite and a ferocious believer in absolute obedience to political authority. He wanted Germany rid of the Jews ..." Luther's advice "... was literally followed four centuries later by Hitler, Goering and Himmler." [18]

Roland Bainton, noted church historian and Luther biographer, wrote with reference to On the Jews and Their Lies: "One could wish that Luther had died before ever this tract was written. His position was entirely religious and in no respect racial"[19]. This is later echoed by James M. Kittelson writing about Luther's correspondence with Jewish scholar Josel of Rosheim[20]: "There was no anti-Semitism in this response. Moreover, Luther never became an anti-Semite in the modern, racial sense of the term."

Gordon Rupp gives this evaluation of On the Jews and Their Lies: "I confess that I am ashamed as I am ashamed of some letters of St. Jerome, some paragraphs in Sir Thomas More, and some chapters in the Book of Revelation, and, must say, as of a deal else in Christian history, that their authors had not so learned Christ." [21]

According to Heiko Oberman, "[t]he basis of Luther's anti-Judaism was the conviction that ever since Christ's appearance on earth, the Jews have had no more future as Jews."[22]

Richard Marius views Luther's remarks as part of a pattern of similar statements about various groups Luther viewed as enemies of Christianity. He states:

"Although the Jews for him were only one among many enemies he castigated with equal fervor, although he did not sink to the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition against Jews, and although he was certainly not to blame for Adolf Hitler, Luther's hatred of the Jews is a sad and dishonorable part of his legacy, and it is not a fringe issue. It lay at the center of his concept of religion. He saw in the Jews a continuing moral depravity he did not see in Catholics. He did not accuse papists of the crimes that he laid at the feet of Jews."[23]

In 1988 Lutheran theologian Stephen Westerholm argued that Luther's attacks on Jews were part and parcel of his attack on the Catholic Church — that Luther was applying a Pauline critique of Phariseism as legalistic and hypocritical to the Catholic Church. Westerholm rejects Luther's interpretation of Judaism and his apparent anti-Semitism but points out that whatever problems exist in Paul's and Luther's arguments against Jews, what Paul, and later, Luther, were arguing for was and continues to be an important vision of Christianity.

Reactions of Christian church bodies and other Religions

Lutherans

In 1983, the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, noting that "Anti-Semitism and other forms of racism are a continuing problem in our world," made an official statement[24] disassociating themselves from what they describe as "intemperate remarks about Jews" in Luther's works.

In 1994, the Church Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America publicly rejected[25] what it described as "Luther's anti-Judaic diatribes and the violent recommendations of his later writings against the Jews," and their "appropriation... by modern anti-Semites for the teaching of hatred toward Judaism or toward the Jewish people in our day."

The statement by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada to the Jewish Community in Canada issued in 1995 says in part:

"Lutherans belonging to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada carry a special burden in this matter because of the anti-Semitic statements made by Martin Luther and because of the suffering inflicted on Jews during the Holocaust in countries and places where the Lutheran Church is strongly represented."[26]

In 1998, the Austrian Evangelical Church declared that

"not only individual Christians but also our churches share in the guilt of the Holocaust/Shoah. ... we as Protestant Christians are burdened by the late writings of Luther and their demand for expulsion and persecution of the Jews. We reject the contents of these writings."[27].

In the same year, the Land Synod of the Lutheran Church of Bavaria issued a declaration[28] saying in part:

"It is imperative for the Lutheran Church, which knows itself to be indebted to the work and tradition of Martin Luther, to take seriously also his anti-Jewish utterances, to acknowledge their theological function, and to reflect on their consequences. ... The Lutheran Church of Bavaria... knows itself to be co-responsible for anti-Jewish thoughts and actions that made possible or at least tolerated the crimes of the "Third Reich" against children, women, and men of Jewish origin. Although there were in the Lutheran Church of Bavaria some individuals who recognized the issue (for example, Wilhelm von Pechmann, Karl Steinbauer, Friedrich Seggel, Wilhelm Geyer), the church as a whole did not take seriously the so-called Jewish Question as a theological issue.

Notes

- ^ Paul Johnson: A History of the Jews, 1987. p.242

- ^ Siemon-Netto, Uwe. "Luther and the Jews." Lutheran Witness 123 (2004)No. 4:19.

- ^ Martin Luther, On the Jews and Their Lies, Trans. Martin H. Bertram, in Luther's Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971), 267.

- ^ "Martin Luther's Letter to George Spalatin," from Luther's Correspondence and Other Contemporaneous Letters, trans. by P. Smith (1913), vol. 1, pp. 28-29 quoted in Overview of 2000 Years of Jewish Persecution. Anti-Judaism: 1201 to 1800 CE http://www.religioustolerance.org/jud_pers3.htm (Retrieved December 15, 2005).

- ^ Halsall http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/1543-Luther-JewsandLies-full.html (Retrieved January 4, 2005)

- ^ Luther quoted in Elliot Rosenberg, But Were They Good for the Jews?, 1997. p.65

- ^ Martin Brecht, Martin Luther, vol. 3, p. 336

- ^ On the Jews and Their Lies (1543), Martin Bertram, trans. in Luther's Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971) vol. 47, 268-288, 292.

- ^ Reformation at Florida Holocaust Museum, http://www.flholocaustmuseum.org. (Retrieved December 15, 2005).

- ^ Luther, Martin: Works. Weimar ed., vol. 51, p. 195

- ^ Main Website: http://www.humanitas-International.org

- ^ Gordon Rupp, Martin Luther: Hitler's Cause or Cure? (London: Lutterworth Press, 1945), 75.

- ^ Rupp, 84.

- ^ Michael, Robert. Luther, Luther Scholars and the Jews 1985 Encounter. Indianapolis, IN: Christian Theological Seminary 46, 4 (Fall 1985) 339-356. Dr. Robert Michael is a 1997 recipient of the American Historical Association's James Harvey Robinson Prize for the "most outstanding contribution to the teaching and learning of history," Dr. Michael is Professor Emeritus of European History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, where he has taught the Holocaust for nearly thirty years. He has published more than 50 articles and eleven books on the Holocaust and the History of Antisemitism.

- ^ D G Myers. Luther's Antisemitism. h-antisemitism 2/18/1998.

- ^ Paul Johnson: A History of the Jews, 1987. p.242

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation, 2003. p.666-667.

- ^ William L. Shirer, Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich ISBN 0671728687, 1990. p.236

- ^ Bainton. Here I Stand. Nashville: Abingdon Press, New American Library, 1983, p. 297

- ^ Kittelson. Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1986, p. 274

- ^ Rupp, 76.

- ^ Heiko Oberman: The Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Age of Renaissance and Reformation, 1984. p.46

- ^ Richard Marius Martin Luther: The Christian Between God and Death Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999). p.482.

- ^ Q&A: Luther's Anti-Semitism at Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, www.lcms.org. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- ^ Declaration of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America to the Jewish Community, April 18, 1994, www.elca.org. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- ^ Statement by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada to the Jewish Communities in Canada. 5th Biannual Convention of the ELCIC, July 12 - 16, 1995. Retrieved December 20, 2005.

- ^ Time to Turn. The Evangelical [Protestant] Churches in Austria and the Jews. Declaration of the General Synod of the Evangelical Church A.B. and H.B. (October 28, 1998). Retrieved December 18, 2005.

- ^ Christians and Jews A Declaration of the Lutheran Church of Bavaria] (November 24, 1998). Retrieved December 18, 2005. Also printed in Freiburger Rundbrief, vol. 6, no. 3 (1999), pp.191-197.

Bibliography

- Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1978. ISBN 0687168945.

- Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther, 3 vols. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1985-1993. ISBN 0800607384, ISBN 0800624637, ISBN 0800627040.

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0060915331.

- Kittelson, James M. Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1986. ISBN 0806622407.

- Luther, Martin. "On the Jews and Their Lies, 1543" Translated by Martin H. Bertram. In Luther's Works Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971. 47:137-306

- Oberman, Heiko A. The Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Age of Renaissance and Reformation. James I. Porter, trans. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984. ISBN 0800607090

- Rupp, Gordon. Martin Luther: Hitler's Cause or Cure? In Reply to Peter F. Wiener. London: Lutterworth Press, 1945.

- Siemon-Netto, Uwe. The Fabricated Luther: the Rise and Fall of the Shirer myth. Peter L. Berger, Foreward. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1995. ISBN 0570048001.

- Siemon-Netto, Uwe. "Luther and the Jews." Lutheran Witness 123 (2004)No. 4:16-19. [[29]]

- Tjernagel, Neelak S. Martin Luther and the Jewish People. Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House, 1985. ISBN 0810002132

External links

- On the Jews and their Lies (excerpts) at Medieval Sourcebook

- Martin Luther and the Jews (PDF) by Albrecht, Mark. Essays Online Mequon, WI: Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary, 1999.

- Antisemitism - Reformation from the Florida Holocaust Museum.

- Luther and the Jews (PDF) by Siemon-Netto, Uwe. Lutheran Witness 123 (2004) No. 4:16-19.

- Martin Luther article in Jewish Encyclopedia (1906 ed.) by Gotthard Deutsch

- Martin Luther - Hitler's Spiritual Ancestor by Peter F. Wiener

- Martin Luther’s Attitude Toward The Jews by James Swan