4 Vesta

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers |

| Discovery date | March 29, 1807 |

| Designations | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈvɛstə/, Latin: Vesta |

| Main belt (Vesta family) | |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |

| Epoch May 14, 2008 (JD 2454600.5) | |

| Aphelion | 384.72 Gm (2.572 AU) |

| Perihelion | 321.82 Gm (2.151 AU) |

| 353.268 Gm (2.361 AU) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.089 17 |

| 1325.15 d (3.63 a) | |

Average orbital speed | 19.34 km/s |

| 90.53° | |

| Inclination | 7.135° to Ecliptic 5.56° to Invariable plane[2] |

| 103.91° | |

| 149.83° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 578×560×458 km[3] 529 km (mean) |

| Mass | (2.67 ± 0.02)×1020 kg[4] |

Mean density | 3.42 g/cm³[4] |

| 0.22 m/s² | |

| 0.35 km/s | |

| 0.222 6 d (5.342 h)[1][5] | |

| Albedo | 0.423 (geometric)[6] |

| Temperature | min: 85 K (−188 °C) max: 255 K (−18 °C)[7] |

Spectral type | V-type asteroid[1][8] |

| 5.1[9] to 8.48 | |

| 3.20[1][6] | |

| 0.64" to 0.20" | |

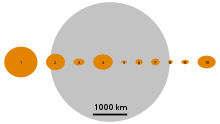

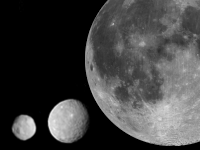

4 Vesta is the second most massive object in the asteroid belt, with a mean diameter of about 530 km[1] and an estimated mass of 9% of the mass of the entire asteroid belt.[10] It was discovered by the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers on March 29, 1807,[1] and named after the Roman virgin goddess of home and hearth, Vesta.

Vesta lost some 1% of its mass in a collision less than one billion years ago. Many fragments of this event have fallen to Earth as Howardite-Eucrite-Diogenite (HED) meteorites, a rich source of evidence about the asteroid.[11] Vesta is the brightest asteroid. Its greatest distance from the Sun is slightly more than the minimum distance of Ceres from the Sun,[12] and its orbit is entirely within the orbit of Ceres.[13]

Discovery

Vesta was discovered by the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers on March 29, 1807. He announced the discovery in a letter addressed to Johann H. Schröter dated March 31, and reported the asteroid's location in the constellation Virgo.[14] Olbers allowed the prominent mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss to name the asteroid after the Roman virgin goddess of home and hearth, Vesta.[15] The mathematician manually computed the first orbit for Vesta in the remarkably short time of 10 hours.[16][17]

Olber's search began in 1802 when he sent a letter to the English astronomer William Herschel proposing that both Ceres and Pallas were the remnants of a destroyed planet. He suggested that a search near the locations where the orbits of these two objects came the closest to intersected may reveal more fragments. These orbital intersections were located in the constellations of Cetus and Virgo.[18]

After the discovery of Vesta in 1807, no further asteroids were discovered for 38 years.[19] During this time the four known asteroids were counted among the planets, and each had its own planetary symbol. Vesta was normally represented by a stylized hearth (![]() , ⚶). Other symbols are Old symbol of Vesta and

, ⚶). Other symbols are Old symbol of Vesta and ![]() . All are simplifications of the original

. All are simplifications of the original ![]() .[20]

.[20]

Photometric observations of the asteroid Vesta were made at the Harvard College Observatory between 1880–82 and at the Observatoire de Toulouse in 1909. These and other observations allowed the rotation rate of the asteroid to be determined by the 1950s. However, the early estimates of the rotation rate came into question because the light curve included variations in both shape and albedo.[21]

Early estimates of the diameter of Vesta ranged from 383 (in 1825) to 444 km. William H. Pickering produced a estimated diameter of 513 ± 17 in 1879, which is close to the modern value for the mean diameter, but the subsequent estimates ranged from a low of 390 km up to a high of 602 km during the next century. The measured estimates were first based on photometry, then later on micrometers and a device called a diskmeter. In 1989, speckle interferometery was used to measure a dimension that varied between 498 and 548 km during the rotational period.[22] In 1991, an occultation of the star SAO 93228 by Vesta was observed from multiple locations in the eastern US and Canada. Based on observations from 14 different sites, the best fit to the data is an elliptical profile with dimensions of about 550 km × 462 km.[23]

Physical characteristics

Vesta is the second-most massive body in the asteroid belt,[4] though only 28% as massive as Ceres.[10] It lies in the Inner Main Belt interior to the Kirkwood gap at 2.50 AU. It has a differentiated interior,[25] and is similar to 2 Pallas in volume (to within uncertainty) but about 25% more massive.[4]

Vesta's shape is relatively close to a gravitationally relaxed oblate spheroid,[26] but the large concavity and protrusion at the pole (see 'Surface features' below) combined with a mass less than 5×1020 kg precluded Vesta from automatically being considered a dwarf planet under International Astronomical Union (IAU) Resolution XXVI 5.[27] Vesta may be listed as a dwarf planet in the future, if it is convincingly determined that its shape, other than the large impact basin at the southern pole, is due to hydrostatic equilibrium, as currently believed.[25]

Its rotation is relatively fast for an asteroid (5.342 h) and prograde, with the north pole pointing in the direction of right ascension 20 h 32 min, declination +48° (in the constellation Cygnus) with an uncertainty of about 10°. This gives an axial tilt of 29°.[26]

Temperatures on the surface have been estimated to lie between about −20 °C with the Sun overhead, dropping to about −190 °C at the winter pole. Typical day-time and night-time temperatures are −60 °C and −130 °C, respectively. This estimate is for May 6, 1996, very close to perihelion, while details vary somewhat with the seasons.[7]

Geology

There is a large collection of potential samples from Vesta accessible to scientists, in the form of over 200 HED meteorites, giving insight into Vesta's geologic history and structure.

Vesta is thought to consist of a metallic iron–nickel core, an overlying rocky olivine mantle, with a surface crust. From the first appearance of Ca-Al-rich inclusions (the first solid matter in the Solar System, forming about 4567 million years ago), a likely time line is as follows:[28][29][30]

Timeline of the evolution of Vesta 2–3 million years Accretion completed 4–5 million years Complete or almost complete melting due to radioactive decay of 26Al, leading to separation of the metal core 6–7 million years Progressive crystallization of a convecting molten mantle. Convection stopped when about 80% of the material had crystallized Extrusion of the remaining molten material to form the crust, either as basaltic lavas in progressive eruptions, or possibly forming a short-lived magma ocean. The deeper layers of the crust crystallize to form plutonic rocks, while older basalts are metamorphosed due to the pressure of newer surface layers. Slow cooling of the interior

Vesta is the only known intact asteroid that has been resurfaced in this manner. However, the presence of iron meteorites and achondritic meteorite classes without identified parent bodies indicates that there once were other differentiated planetesimals with igneous histories, which have since been shattered by impacts.

Composition of the Vestan crust (in order of increasing depth)[31] A lithified regolith, the source of howardites and brecciated eucrites. Basaltic lava flows, a source of non-cumulate eucrites. Plutonic rocks consisting of pyroxene, pigeonite and plagioclase, the source of cumulate eucrites. Plutonic rocks rich in orthopyroxene with large grain sizes, the source of diogenites.

On the basis of the sizes of V-type asteroids (thought to be pieces of Vesta's crust ejected during large impacts), and the depth of the south polar crater (see below), the crust is thought to be roughly 10 kilometres (6 mi) thick.[32]

Surface features

Some Vestian surface features have been resolved using the Hubble Space Telescope and ground based telescopes, e.g. the Keck Telescope.[33]

The most prominent surface feature is an enormous crater 460 kilometres (290 mi)* in diameter centered near the south pole.[26] Its width is 80% of the entire diameter of Vesta. The floor of this crater is about 13 kilometres (8.1 mi)* below, and its rim rises 4–12 km above the surrounding terrain, with total surface relief of about 25 km. A central peak rises 18 kilometres (11 mi)* above the crater floor. It is estimated that the impact responsible excavated about 1% of the entire volume of Vesta, and it is likely that the Vesta family and V-type asteroids are the products of this collision. If this is the case, then the fact that 10 km fragments of the Vesta family and V-type asteroids have survived bombardment until the present indicates that the crater is only about 1 billion years old or younger.[34] It would also be the original site of origin of the HED meteorites. In fact, all the known V-type asteroids taken together account for only about 6% of the ejected volume, with the rest presumably either in small fragments, ejected by approaching the 3:1 Kirkwood gap, or perturbed away by the Yarkovsky effect or radiation pressure. Spectroscopic analyses of the Hubble images have shown that this crater has penetrated deep through several distinct layers of the crust, and possibly into the mantle, as indicated by spectral signatures of olivine.[26]

Several other large craters about 150 kilometres (93 mi)* wide and 7 kilometres (4.3 mi)* deep are also present. A dark albedo feature about 200 kilometres (120 mi)* across has been named Olbers in honour of Vesta's discoverer, but it does not appear in elevation maps as a fresh crater would. Its nature is presently unknown; it may be an old basaltic surface.[35] It serves as a reference point with the 0° longitude prime meridian defined to pass through its center.

The eastern and western hemispheres show markedly different terrains. From preliminary spectral analyses of the Hubble Space Telescope images,[34] the eastern hemisphere appears to be some kind of high albedo, heavily cratered "highland" terrain with aged regolith, and craters probing into deeper plutonic layers of the crust. On the other hand, large regions of the western hemisphere are taken up by dark geologic units thought to be surface basalts, perhaps analogous to the lunar maria.[34]

Fragments

Some small solar system objects are believed to be fragments of Vesta caused by collisions. The Vestoid asteroids and HED meteorites are examples. The V-type asteroid 1929 Kollaa has been determined to have a composition akin to cumulate eucrite meteorites, indicating its origin deep within Vesta's crust.[11]

Because a number of meteorites are believed to be Vestian fragments, Vesta is currently one of only five identified Solar system bodies for which we have physical samples, the others being Mars, the Moon, comet Wild 2, and Earth itself.

Exploration

The first space mission to Vesta will be NASA's Dawn probe—launched on September 27, 2007—which will orbit the asteroid for nine months from August 2011 until May 2012.[36] Dawn will then proceed to its other target, Ceres, and will probably continue to explore the asteroid belt on an extended mission using remaining fuel. The spacecraft is the first that can enter and leave orbit around more than one body as a result of its weight-efficient ion driven engines.[36] Once Dawn arrives at Vesta, scientists will be able to calculate Vesta's precise mass based on gravitational interactions. This will allow scientists to refine the mass estimates of the asteroids that are in turn perturbed by Vesta.[36]

Visibility

Its size and unusually bright surface make Vesta the brightest asteroid, and it is occasionally visible to the naked eye from dark (non-light polluted) skies. In May and June 2007, Vesta reached a peak magnitude of +5.4, the brightest since 1989.[37] At that time, opposition and perihelion were only a few weeks apart. It was visible in the constellations Ophiuchus and Scorpius.[38]

Less favorable oppositions during late autumn in the Northern Hemisphere still have Vesta at a magnitude of around +7.0. Even when in conjunction with the Sun, Vesta will have a magnitude around +8.5; thus from a pollution-free sky it can be observed with binoculars even at elongations much smaller than near opposition.[39]

February 2010

In 2010, Vesta reaches opposition in the constellation of Leo on the night of February 17–18, when it is expected to shine at magnitude 6.1,[40] a brightness that makes it visible in binocular range but probably not for the naked eye. However, under perfect dark sky conditions where all light pollution is absent it might be visible to an experienced observer without the use of any telescope or a binocular.

See also

- 3103 Eger

- 4055 Magellan

- 3908 Nyx

- 3551 Verenia

- V-type asteroid

- HED meteorites

- Diogenite

- Eucrite

- Howardite

- Asteroids in fiction

- List of Solar System bodies formerly considered planets

Notes and references

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 4 Vesta". Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ^ "The MeanPlane (Invariable plane) of the Solar System passing through the barycenter". 2009-04-03. Retrieved 2009-04-10. (produced with Solex 10 written by Aldo Vitagliano; see also Invariable plane)

- ^ Thomas, P. C.; et al. (1997). "Impact excavation on asteroid 4 Vesta: Hubble Space Telescope results". Science. 277: 1492. doi:10.1126/science.277.5331.1492.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c d Baer, James (2008). "Astrometric masses of 21 asteroids, and an integrated asteroid ephemeris" (PDF). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 100 (2008). Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2007: 27–42. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9103-8. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Harris, A. W. (2006). "Asteroid Lightcurve Derived Data. EAR-A-5-DDR-DERIVED-LIGHTCURVE-V8.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Tedesco, E. F. (2004). "Infra-Red Astronomy Satellite (IRAS) Minor Planet Survey. IRAS-A-FPA-3-RDR-IMPS-V6.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mueller, T. G. (2001). "ISO and Asteroids" (PDF). European Space Agency (ESA) bulletin. 108: 38.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Neese, C. (2005). "Asteroid Taxonomy EAR-A-5-DDR-TAXONOMY-V5.0". NASA Planetary Data System. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Menzel, Donald H.; and Pasachoff, Jay M. (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 391. ISBN 0395348358.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pitjeva, E. V. (2005). "High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants" (PDF). Solar System Research. 39 (3): 176. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2.

- ^ a b Kelley, M. S. (2003). "Quantified mineralogical evidence for a common origin of 1929 Kollaa with 4 Vesta and the HED meteorites". Icarus. 165: 215. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00149-0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ On February 10, 2009, during Ceres perihelion, Ceres was closer to the Sun than Vesta since Vesta has an aphelion distance greater than Ceres' perihelion distance. (2009-02-10: Vesta 2.56AU; Ceres 2.54AU)

- ^ "Ceres, Pallas Vesta and Hygiea". Gravity Simulator. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- ^ Lynn, W. T. (1907). "The discovery of Vesta". The Observatory. 30: 103–105. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names: Prepared on Behalf of Commission 20 Under the Auspices of the International Astronomical Union. Springer. p. 15. ISBN 3540002383.

- ^ Dunnington, Guy Waldo; Gray, Jeremy; Dohse, Fritz-Egbert (2004). Carl Friedrich Gauss: Titan of Science. The Mathematical Association of America. p. 76. ISBN 088385547X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rao, K. S.; Berghe, G. V. (2003). "Gauss, Ramanujan and Hypergeometric Series Revisited". Historia Scientiarum. 13 (2): 123–133.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Littmann, Mark (2004). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier Dover Publications. p. 21. ISBN 0486436020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Wells, David A. (1851). "The Planet Hygiea". Annual of Scientific Discovery for the year 1850, quoted by spaceweather.com archives, 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Older form and discussion of its complexity from Gould, 1852 (Gould, B. A. (1852), On the Symbolic Notation of the Asteroids, Astronomical Journal, 2, as cited and discussed at http://aa.usno.navy.mil/faq/docs/minorplanets.php.

- ^ McFadden, L. A.; Emerson, G.; Warner, E. M.; Onukwubiti, U.; Li, J.-Y. (March 10–14, 2008). "Photometry of 4 Vesta from its 2007 Apparition". Proceedings, 39th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. League City, Texas. Bibcode:2008LPI....39.2546M. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hughes, D. W. (1994). "The Historical Unravelling of the Diameters of the First Four Asteroids". The Royal Astronomical Journal Quarterly Journal. 35 (3). Bibcode:1994QJRAS..35..331H. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Povenmire, H. (2001). "The January 4, 1991 Occultation of SAO 93228 by Asteroid (4) Vesta". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 36 (Supplement): A165. Bibcode:2001M&PSA..36Q.165P.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ O. Gingerich (2006). "The Path to Defining Planets" (PDF). Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and IAU EC Planet Definition Committee chair. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ a b Savage, Don (1995). "Asteroid or Mini-Planet? Hubble Maps the Ancient Surface of Vesta". Hubble Site News Release STScI-1995-20. Retrieved 2006-10-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Thomas, P. C.; et al. (1997). "Vesta: Spin Pole, Size, and Shape from HST Images". Icarus. 128: 88. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5736.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "The IAU draft definition of "planet" and "plutons"". IAU. August 2006. Retrieved 2009-12-16. (XXVI)

- ^ Ghosh, A. (1998). "A Thermal Model for the Differentiation of Asteroid 4 Vesta, Based on Radiogenic Heating". Icarus. 134: 187. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5956.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Righter, K. (1997). "A magma ocean on Vesta: Core formation and petrogenesis of eucrites and diogenites". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 32: 929–944.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Drake, M. J. (2001). "The eucrite/Vesta story". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 36: 501–513.

- ^ Takeda, H. (1997). "Mineralogical records of early planetary processes on the HED parent body with reference to Vesta". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 32: 841–853.

- ^ Yamaguchi, A. (1995). "Metamorphic History of the Eucritic Crust of 4 Vesta". Meteoritical Society. 30: 603. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zellner, N. E. B. (2005). "Near-IR imaging of Asteroid 4 Vesta" (pdf). Icarus. 177: 190–195. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.03.024.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Binzel, R. P. (1997). "Geologic Mapping of Vesta from 1994 Hubble Space Telescope Images". Icarus. 128: 95. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5734.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zellner, B. J. (1997). "Hubble Space Telescope Images of Asteroid Vesta in 1994". Icarus. 128: 83. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5735.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Russell, C. T. (2007). "Dawn Mission to Vesta and Ceres". Earth Moon Planet. 1001: 65–91. doi:10.1007/s11038-007-9151-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bryant, Greg (2007). "Sky & Telescope: See Vesta at Its Brightest!". Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Vesta Finder". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ James, Andrew (2008). "Vesta". Southern Astronomical Delights. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Donald K. Yeomans and Alan B. Chamberlin. "Horizons Ephemeris". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

General references

- Yeomans, Donald K. "Horizons system". NASA JPL. Retrieved 2007-03-20. – Horizons can be used to obtain a current ephemeris

- Keil, K.; Geological History of Asteroid 4 Vesta: The Smallest Terrestrial Planet in Asteroids III, William Bottke, Alberto Cellino, Paolo Paolicchi, and Richard P. Binzel, (Editors), University of Arizona Press (2002), ISBN 0-8165-2281-2

External links

- NASA's Dawn Spacecraft will reach orbit around Vesta in July 2011.

- NASA video clips of Vesta rotating in color

- Views of the Solar System: Vesta

- HubbleSite: Hubble Maps the Asteroid Vesta

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vesta – full article

- HubbleSite: Hubble Reveals Huge Crater on the Surface of the Asteroid Vesta

- HubbleSite: short movie composed from Hubble Space Telescope images from November 1994.

- Adaptive optics views of Vesta from Keck Observatory

- Differentiated interior of Vesta

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Horizons Ephemeris

- 4 Vesta images at ESA/Hubble

- Hubble views of Vesta on the Planetary Society Weblog (includes animation)

- Farinella, Paolo (2005). "Houston: Focus on Vesta and the HEDs". Arkansas Center for Space & Planetary Sciences. Retrieved 2007-10-25.