Incense

Incense (Latin: incendere, "to burn")[1] is composed of aromatic biotic materials, which release fragrant smoke when burned. The term "incense" refers to the substance itself, rather than to the odor that it produces. It is used in religious ceremonies, ritual purification, aromatherapy, meditation, for creating a mood, masking bad odours, and in medicine.[2][3][4] The use of incense may have originated in Ancient Egypt, where the gums and resins of aromatic trees were imported from the Arabian and Somali coasts to be used in religious ceremonies.

Incense is composed of aromatic plant materials, often combined with essential oils.[5] The forms taken by incense have changed with advances in technology, differences in the underlying culture, and diversity in the reasons for burning it.[6] The two main types can generally be separated into "indirect burning" and "direct burning". Indirect burning incense, also called "non-combustible incense", requires a separate heat source since it is not capable of burning itself. Direct burning incense, also called "combustible incense", is lit directly by a flame and then fanned out, the glowing ember on the incense will smoulder and release fragrance. Examples of direct burning incense are incense sticks (joss sticks) and cones or pyramids.

History

The use of incense dates back to biblical times and may have originated in Egypt, where the gums and resins of aromatic trees were imported from the Arabian and Somali coasts to be used in religious ceremonies. It was also used by the Pharaohs, not only to counteract unpleasant odours, but also to drive away demons and gratify the presence of the gods, as they believed.[2]

The Babylonians used incense while offering prayers to divining oracles.[7] The Indus Civilization used incense burners.[8] Evidence suggests oils were used mainly for their aroma. Incense spread from there to Greece and Rome. Brought to Japan in the 6th century by Chinese Buddhist monks, who used the mystical aromas in their purification rites, the delicate scents of Koh (high-quality Japanese incense) became a source of amusement and entertainment with nobles in the Imperial Court during the Heian Era 200 years later.

During the 14th century Shogunate, samurai warriors would perfume their helmets and armor with incense to achieve an aura of invincibility. It wasn't until the Muromachi Era during the 15th and 16th century that incense appreciation (Kōdō) spread to the upper and middle classes of Japanese society.

Composition

Throughout history, a wide variety of materials have been used in making incense. Historically there has been a preference for using locally available ingredients. For example, sage and cedar were used by the indigenous peoples of North America.[9] This was a preference and ancient trading in incense materials from one area to another comprised a major part of commerce along the Silk Road and other trade routes, one notably called the Incense Route.

The same could be said for the techniques used to make incense. Local knowledge and tools were extremely influential on the style, but methods were also influenced by migrations of foreigners, among them clergy and physicians who were both familiar with incense arts.[6]

Natural solid aromatics

The following fragrance materials can be employed in either direct or indirect burning incense. They are commonly used in religious ceremonies, and many of them are considered quite valuable. Essential oils or other extracted fractions of these materials may also be isolated and used to make incense. The resulting incense is sometimes considered to lack the aromatic complexity or authenticity of incense made from raw materials not infused or fortified with extracts.

Woods and barks

Seeds and fruits

Resins and gums

Leaves

Roots and rhizomes

Flowers and buds

Animal-derived materials

Liquid aromatics

Many essential oils and artificial fragrances are used for scenting incense. Incense deriving its aroma primarily from essential oils is usually cheaper than that made from unextracted raw materials. Even cheaper are artificial fragrances used in incense, which are derived from chemical synthesis. Liquid aromatics are usually added to a base formed from charcoal powder.

Essential oils

Artificial scents

Combustible base

The combustible base of a direct burning incense mixture not only binds the fragrant material together but also allows the produced incense to burn with a self-sustained ember, which propagates slowly and evenly through an entire piece of incense with such regularity that it can be used to mark time. The base is chosen such that it does not produce a perceptible smell. Commercially, two types of incense base predominate:

- Fuel and oxidizer mixtures: Charcoal or wood powder forms the fuel for the combustion. Gums such as Gum Arabic or Gum Tragacanth are used to bind the mixture together while an oxidizer such as Sodium nitrate or Potassium nitrate sustains the burning of the incense. Fragrant materials are combined into the base prior to formation as in the case of powdered incense materials or after formation as in the case of essential oils. The formula for the charcoal based incense is superficially similar to black powder, though it lacks the sulfur.

- Natural plant-based binders: Mucilaginous material, which can be derived from many botanical sources, is mixed with fragrant materials and water. The mucilage from the wet binding powder holds the fragrant material together while the cellulose in the powder combusts to form a stable ember when lit. The dry binding powder usually comprises about 10% of the dry weight in the finished incense. This includes Makko (抹香・末香 incense powder), which is made from the bark of various trees from the Persea genus such as Persea nanmu or Persea thunbergii (Jpn. 椨の木; たぶのき; Tabu-no-ki) and xiangnan pi (香楠皮) made from Phoebe genus trees such as Phoebe nanmu (楠木), Persea zuihensis (香楠). In India a resin based binder called Jigit is used. In Nepal, Tibet, and other East Asian countries a bark based powder called Laha or Dar is used.

Types

Incense is available in various forms and degrees of processing. They can generally be separated into "direct burning" and "indirect burning" types depending on use. Preference for one form or another varies with culture, tradition, and personal taste. Although the production of direct and indirect burning incense are both blended to produce a pleasant smell when burned, the two differ in their composition due to the former's requirement for even, stable, and sustained burning.

Indirect burning

Indirect burning incense, also called "non-combustible incense",[10] is a combination of aromatic ingredients not prepared in any particular way or encouraged into any particular form, leaving it mostly unsuitable for direct combustion. The use of this class of incense requires a separate heat source since it does not generally kindle a fire capable of burning itself and may not ignite at all under normal conditions. This incense can vary in the duration of its burning with the texture of the material. Finer ingredients tend to burn more rapidly, while coarsely ground or whole chunks may be consumed very gradually as they have less total surface area. The heat is traditionally provided by charcoal or glowing embers.

The best known incense materials of this type in the West, are frankincense and myrrh, likely due to their numerous mentions in the Christian Bible. In fact, the word for "frankincense" in many European languages also alludes to any form of incense.

- Whole: The incense material is burned directly in its raw unprocessed form on top of coal embers.

- Powdered or granulated: The incense material is broken down into finer bits. This incense burns quickly and provides a short period of intense smells.

- Paste: The powdered or granulated incense material is mixed with a sticky and incombustible binder, such as dried fruit, honey, or a soft resin and then formed to balls or small pastilles. These may then be allowed to mature in a controlled environment where the fragrances can commingle and unite. Much Arabian incense, also called "Bukhoor" or "Bakhoor", is of this type, and Japan has a history of kneaded incense, called nerikō or awasekō, using this method.[11] Within the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition raw frankincense is ground into a fine powder and then mixed with various sweet smelling essential oils.

- Production

Indirect burning incense does not have any stringent requirements except for achieving pleasant smell when lit. Mixture of incense materials can be combined by powdering the raw materials and then mixing together with a binder to form pastes, which are then cut and dried into pellets.

Incense of the Athonite Orthodox Christian tradition are made using similar methods by powdering frankincense or fir resin, mixing it with essential oils. Floral fragrances are the most common, but citrus such as lemon is not uncommon. The incense mixture is then rolled out into a slab approximately 1cm thick and left until the slab has firmed. It is then cut into small cubes, coated with powder clay to prevent adhesion, and allowed to fully harden and dry.[12][13] The product visually resemble cubes of Loukoum.

Direct burning

Direct burning incense also called "combustible incense",[10] generally requires little preparation prior to its use. When lit directly by a flame (hence the appellation) and then fanned out, the glowing ember on the incense will continue to smoulder and burn away the rest of the incense without continued application of heat or flame from an outside source. This class of incense is made from a moldable substrate of fragrant finely ground (or liquid) incense materials and odourless binder.[6] The composition must be adjusted to provide fragrance in the proper concentration and to ensure even burning. The following types of direct burning incense are commonly encountered, though the material itself can take virtually any form, according to expediency or whimsy:

- Coil: Extruded and shaped into a coil without a core. This type of incense is able to burn for an extended period; from hours to days and is commonly produced and used by Chinese culture

- Cone: Incense in this form burns relatively fast. Cone incense containing mugwort are used in Traditional Chinese medicine for moxibustion treatment.

- Cored stick: This form of stick incense has a supporting core of bamboo. Higher quality varieties of this form have fragrant sandalwood cores. The core is coated by a thick layer of incense material that burns away with the core. This type of incense is commonly produced in India and China. When used for worship in Chinese folk religion, cored incensed sticks are sometimes known as "joss sticks".

- Solid stick: This stick incense has no supporting core and is completely made of incense material. Easily broken into pieces, it allows one to determine the specific amount of incense they wish to burn. This is the most commonly produced form of incense in Japan and Tibet.

- Loose powder: The incense powder used for making indirect burning incense is sometimes burned without further processing. They are typically packed into long trails on top of wood ash using a stencil and burned in special censers or incense clocks.

- Rope: The incense powder is rolled into paper sheets, which are then rolled into ropes, twisted tightly, then doubled-over and twisted again, yielding a two-strand rope. The larger end is the bight, and may be stood vertically, in a shallow dish of sand or pebbles. The smaller (pointed) end is lit. This type of incense is highly transportable and stays fresh for excessively long periods of time. It has been used for centuries in Tibet and Nepal.

Direct burning incense of these forms is either extruded, pressed into forms, or coated onto a supporting material.

- Joss sticks

Joss sticks are used for a variety of purposes, such as to enhance the smell of a room, or to light fire crackers. They are used in many East Asian and Southeast Asian countries, traditionally burned before a Chinese religious image, idol or shrine. They can also be burned in front of a door, or open window as an offering to heaven, or devas. The word "joss" for Joss (god) is derived from the Latin deus (god) via Portuguese.[14][15]

Joss stick burning is an everyday practice in traditional Chinese religion. There are many different types of joss sticks used for different purposes or on different festive days. Many of them are long and thin and are mostly colored yellow, red, and more rarely, black. Thick joss sticks are used for special ceremonies, such as funerals. Spiral joss sticks are also used on a regular basis, which are found hanging above temple ceilings, with burn times that are exceedingly long. In some states, such as Taiwan, Singapore, or Malaysia, where they celebrate the Ghost Festival, large, pillar-like dragon joss sticks are sometimes used.

- Production

Production is quite the opposite for direct burning incense. On top of producing a pleasant scent when burnt, this type of incense must burn completely to a cool white ash with a stable ember. Ideally the incense should burn slowly and evenly with no trace of the supporting core after burning. In order to obtain these desired combustion qualities, attention has to be paid to certain proportions in direct burning incense mixtures:

- Oil content: Resinous materials such as myrrh and frankincense must not exceed the amount of dry materials in the mixture to such a degree that the incense will not smoulder and burn. The higher the oil content relative to the dry mass, the less likely the mixture is to burn effectively. Typically the resinous or oily substances are balanced with "dry" materials such as wood, bark and leaf powders.

- Oxidizer quantity: The amount of chemical oxidizer in gum bound incense must be carefully proportioned. Too little, and the incense will not ignite, too much, and the incense will burn too quickly and not produce fragrant smoke.

- Mixture density: Incense mixture made with natural binders must not be combined with too much water in mixing, or over-compressed while being formed. This either results in uneven air distribution or undesirable density in the mixture, which causes the incense to burn unevenly, too slowly, or too quickly.

- Particulate size: The incense mixture has to be well pulverized with similar size of particulates. Uneven and large particulates will result in uneven burning and may smell inconsistent when burned.

- Binder: Water soluble binders like "makko" (抹香・末香) have to be used in the right proportion to ensure that the incense mixture does not crumble when dry but also that the binder does not take up too much of the mixture [6]

Some direct burning incense are created from "incense blanks". This form is made of unscented combustible dust and then immersed into any kind of essential or fragrance oil. It was made popular in American Flea markets by vendors who wanted their own style and often known as "dipped" or "Hand-dipped". This form requires the least skill and equipment to manufacture since the blanks are pre-formed upon purchase.

Compressed forms

Incense mixtures can be extruded or pressed into shapes. Small quantities of water are combined with the fragrance and incense base mixture and kneaded into a hard dough. The incense dough is then pressed into shaped forms to create cone and smaller coiled incense, or forced through a hydraulic press for solid stick incense. The formed incense is then trimmed and slowly dried. Incense produced in this fashion has a tendency to warp or become misshapen when improperly dried, and as such must be placed in climate controlled rooms and rotated several times through the drying process.

Cored sticks

In the case of cored incensed sticks several methods are employed to coat the sticks cores with incense mixture:

- Paste rolling: A wet malleable paste of incense mixture is first rolled using a paddle into a long thin coil. When this is done a thin stick is then put next to the coil and rolled together until the stick is center in the mixture and a correct thickness of the incense stick is achieved. The stick is then cut to the right length and dried.[16]

- Powder coating: Coating is used mainly to produce cored incense of either larger coil (up to 1 meter in diameter) or cored stick forms. The supporting material, either thin bamboo or sandalwood slivers, are soaked in water or a thin water/glue mixture for a short time. The bundle of thin sticks are then evenly separated then dipped into a tray of incense powder, consisting of fragrance materials and occasionally a plant based binder. The dry incense powder is then tossed and piled over the stick while they are spread apart. The sticks are then gently rolled and packed to maintain roundness while repeatedly tossing more incense powder onto the sticks. Three to four layers of powder are coated onto the sticks, forming a 2 mm thick layer of incense material on the stick. The coated incense is then allowed to dry in open air. Additional coatings of incense mixture can be applied after each period of successive drying. Incense sticks that are burned in temples of Chinese folk religion produced in this fashion can have a thickness between 1 to 2 cm.[17] [18]

- Compression: A damp powder is mechanically formed around a cored stick by compression similar to the way uncored sticks are formed. This form is becoming more commonly found due to the labor cost of producing powder coated or paste rolled sticks.

Burning incense

For indirect burning incense, pieces of the incense are burned by placing it directly on top of the heat source or on a hot metal plate in the censer or thurible.[19]

In Japan a similar censer called a egōro (柄香炉) is used by several Buddhist sects. The egōro is usually made of brass with a long handle (柄, e)) and no chain. Instead of charcoal, makkō powder is poured into a depression made in a bed of ash. The makkō is lit and the incense mixture is burned on top. This method is known as Sonae-kō (Religious Burning).[20]

For direct burning incense, an end of the incense is held against a flame or a heat source until the incense begins to turn into ash at the burning end. Flames on the incense are fanned out and the incense is allowed to burn on its own.

Cultural variations

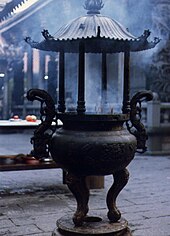

Chinese incense

For over two thousand years, the Chinese have used incense (xiang 香 "fragrance; aroma; perfume; spice; incense") in religious ceremonies, ancestor veneration, Traditional Chinese medicine, and daily life.

As with Japanese incense (see below), agarwood (chenxiang 沈香) and sandalwood (tanxiang 檀香) are the two most important ingredients in Chinese incense.

Along with the introduction of Buddhism in China came calibrated incense sticks and incense clocks (xiangzhong 香鐘" incense clock" or xiangyin 香印 "incense seal").[21] The poet Yu Jianwu 庾肩吾 (487-551) first recorded them: "By burning incense we know the o'clock of the night, With graduated candles we confirm the tally of the watches."[22] The use of these incense timekeeping devices spread from Buddhist monasteries into Chinese secular society.

Indian incense

Indian incense can be divided into two categories: masala and charcoal.

Masala incenses are made by blending several solid scented ingredients into a paste and then rolling that paste onto a bamboo core stick. These incenses usually contain little or no liquid scents (which can evaporate or diminish over time).

Charcoal incenses are made by dipping an unscented "blank" (non-perfume stick) into a mixture of perfumes and/or essential oils. These blanks usually contain a binding resin that holds the sticks' ingredients together. Most charcoal incenses are black in colour.

Jerusalem temple incense

Ketoret was the incense offered in the Temple in Jerusalem and is stated in the Book of Exodus as a mixture of stacte, onycha, galbanum and frankincense.

Tibetan incense

Tibetan incense refers to a common style of incense found in Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan. These incenses have a characteristic "earthy" scent to them. Ingredients vary from cinnamon, clove, and juniper, to kusum flower, ashvagandha, or sahi jeera.

Many Tibetan incenses are thought to have medicinal properties. Their recipes come from ancient Vedic texts that are based on even older Ayurvedic medical texts. The recipes have remained unchanged for centuries.

Japanese incense

Agarwood (沈香 Jinkō) and sandalwood (白檀 Byakudan) are the two most important ingredients in Japanese incense. Agarwood is known as "Jinkō" in Japan, which translates as "incense that sinks in water", due to the weight of the resin in the wood. Sandalwood is one of the most calming incense ingredients and lends itself well to meditation. It is also used in the Japanese tea ceremony. The most valued Sandalwood comes from Mysore in the state of Karnataka in India.

Another important ingredient in Japanese incense is kyara (伽羅). Kyara is one kind of agarwood (Japanese incense companies divide agarwood into 6 categories depending on the region obtained and properties of the agarwood). Kyara is currently worth more than its weight in gold.

Some terms used in Japanese incense culture include:

- Incense Arts: [香道 , Kodo]

- Agarwood: [ 沈香 ] – from heartwood from Aquilaria trees, unique, the incense wood most used in incense ceremony, other names are: lignum aloes or aloeswood, gaharu, jinko, or oud.

- Censer/Incense burner: [香爐] – usually small and used for heating incense not burning, or larger and used for burning

- Charcoal: [木炭] – only the odorless kind is used.

- Incense woods: [ 香木 ] – a naturally fragrant resinous wood.

Uses of incense

Incense, being an article familiar to humanity since the dawn of civilization, has meant different things to the different peoples who have come to use it. Given the wide diversity of such peoples and their practices, it would be impossible to form an all-inclusive list of the ways in which incense has come to be used, since the methods and purposes of employment are as diverse and nuanced as those who have employed it.

Practical use of incense

Incense fragrances can be of such great strength that they obscure other, less desirable odours. This utility led to the use of incense in funerary ceremonies because the incense could smother the scent of decay. Another example of this use, as well as of religious use is the Botafumeiro, which, according to tradition, was installed to hide the scent of the many tired, unwashed pilgrims huddled together in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

The regular burning of direct combustion incense has been used for chronological measurement in incense clocks. These devices can range from a simple trail of incense material calibrated to burn in a specific time period, to elaborate and ornate instruments with bells or gongs, designed to involve and captivate several of the senses.[23]

Incense made from materials such as citronella can repel mosquitoes and other aggravating, distracting or pestilential insects. This use has been deployed in concert with religious uses by Zen Buddhists who claim that the incense that is part of their meditative practice is designed to keep bothersome insects from distracting the practitioner. Currently, more effective pyrethroid-based mosquito repellant incense is widely available in Asia.

Incense is also used often by people who smoke indoors, and do not want the scent to linger.

Aesthetic use of incense

Many people burn incense to appreciate its smell, without assigning any other specific significance to it, in the same way that the forgoing items can be produced or consumed solely for the contemplation or enjoyment of the refined sensory experience. This use is perhaps best exemplified in the kōdō (香道), where (frequently costly) raw incense materials such as agarwood are appreciated in a formalized setting.

Religious use of incense

Use of incense in religion is prevalent in many cultures and may have their roots in the practical and aesthetic uses considering that many religions with not much else in common all use incense. One common motif is incense as a form of sacrificial offering to a deity, for example, Chinese jingxiang (敬香 "offer incense [to ancestors/gods]).

Incense and health

Incense smoke contains various contaminants including gaseous pollutants, such as carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [4–8], and absorbed toxic pollutants (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and toxic metals). The solid particles range between ~10 and 500 nm. The emission rate decreases in the row Indian sandalwood > Japanese aloeswood > Taiwanese aloeswood > smokeless sandalwood.[24] There is no question that those contaminants are carcinogenic and can cause respiratory diseases, but the risk of those depends on the exposure.

Research carried out in Taiwan in 2001 linked the burning of incense sticks to the slow accumulation of potential carcinogens in a poorly ventilated environment by measuring the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (including benzopyrene) within Buddhist temples. The study found gaseous aliphatic aldehydes, which are carcinogenic and mutagenic, in incense smoke.[25]

A survey of risk factors for lung cancer, also conducted in Taiwan, noted an inverse association between incense burning and adenocarcinoma of the lung, though the finding was not deemed significant.[26]

In contrast, a study by several Asian Cancer Research Centers showed: "No association was found between exposure to incense burning and respiratory symptoms like chronic cough, chronic sputum, chronic bronchitis, runny nose, wheezing, asthma, allergic rhinitis, or pneumonia among the three populations studied: i.e. primary school children, their non-smoking mothers, or a group of older non-smoking female controls. Incense burning did not affect lung cancer risk among non-smokers, but it significantly reduced risk among smokers, even after adjusting for lifetime smoking amount." However, the researchers qualified the findings by noting that incense burning in the studied population was associated with certain low-cancer-risk dietary habits, and concluded that "diet can be a significant confounder of epidemiological studies on air pollution and respiratory health."[27]

Frankincense has been shown to cause antidepressive behavior in mice. It activated the poorly understood ion channels in the brain to alleviate anxiety and depression.[28]

Incense lore

Incense folklore includes art, culture, history, and ceremony. It can be compared to and has some of the same qualities as music, art, or literature. Incense is also an integral part of the tea ceremony, just like Calligraphy, Ikebana, and Scroll Arrangement. These are five Classical Chinese Arts. Incense Lore involves natural incense woods and not artificial substitutes.

See also

- Incense Road

- Kōdō, incense arts

- Kyphi

- Silk Road

- Smudge stick

References

- ^ "The History of Incense". www.socyberty.com. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ a b Maria Lis-Balchin (2006). Aromatherapy science: a guide for healthcare professionals. Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 0853695784.

- ^ Gina Hyams, Susie Cushner (2004). Incense: Rituals, Mystery, Lore. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0811839931.

- ^ Carl Neal (2003). Incense: Crafting & Use of Magickal Scents. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 0738703362.

- ^ Cunningham's Encyclopedia of magical herbs. Llewellyn Worldwide. 2000. ISBN 0875421229.

- ^ a b c d David Oller. "Making Incense".

- ^ Foreign trade in the old Babylonian period: as revealed by texts from southern Mesopotamia. Brill Archive. 1960.

- ^ John Marshall (1996). Mohenjo Daro And The Indus Civilization 3 Vols. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8120611799.

- ^ Adrienne Borden and Steve Coyote. "The Smudging Ceremony".

- ^ a b Mark Ambrose. "How to Make Incense".

- ^ Taji Asjikaga. "Incense blending".

- ^ "Athonite style incense from the US".

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Incense".

- ^ Incense at dictionary.reference.com

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "joss". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Making Incense". December 18, 2006.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "台灣宏觀電視TMACTV 代代相傳 新港香藝文化".

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "製香過程". July 20, 2009.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ P. Morrisroe. Transcribed by Kevin Cawley. "Catholic Encyclopedia".

- ^ Japanese-Incense. "Buddhist Incense – Sonae ko".

- ^ Bedini, Silvio A. (1963). "The Scent of Time. A Study of the Use of Fire and Incense for Time Measurement in Oriental Countries". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 53 (5). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Philosophical Society: 1–51. doi:10.2307/1005923. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand, a Study of T'ang Exotics. University of California Press. p. 155.

- ^ Silvio A. Bedini. "Time Measurement With Incense in Japan".

- ^ Siao Wei See; et al. (2007). "Physical characteristics of nanoparticles emitted from incense smoke". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 8: 25. doi:10.1016/j.stam.2006.11.016.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Lin, J M (1994-09). "Gaseous aliphatic aldehydes in Chinese incense smoke". Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 53 (3): 374–381. ISSN 0007-4861. PMID 7919714.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ger LP, Hsu WL, Chen KT, Chen CJ (1993). "Risk factors of lung cancer by histological category in Taiwan". Anticancer Res. 13 (5A): 1491–500. PMID 8239527.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koo, Linda C.; Ho, J.H-C.; Tominaga, Suketami; Matsushita, Hidetsuru; Matsuki, Hideaki; Shimizu, Hiroyuki; Mori, Toru (11/01/1995). "Is Chinese Incense Smoke Hazardous to Respiratory Health?: Epidemiological Results from Hong Kong". Indoor and Built Environment. 4 (6): 334. doi:10.1177/1420326X9500400604.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Moussaieff A, Rimmerman N, Bregman T; et al. (2008). "Incensole acetate, an incense component, elicits psychoactivity by activating TRPV3 channels in the brain". FASEB J. 22 (8): 3024–34. doi:10.1096/fj.07-101865. PMC 2493463. PMID 18492727.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

Further reading

- Silvio A. Bedini. (1994). "The Trail of Time: Time Measurement with Incense in East Asia". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37482-0

External links

- Moussaieff A, Shohami E, Kashman Y; et al. (2007). "Incensole acetate, a novel anti-inflammatory compound isolated from Boswellia resin, inhibits nuclear factor-κ B activation". Mol. Pharmacol. 72 (6): 1657–64. doi:10.1124/mol.107.038810. PMID 17895408.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Frankincense and Myrrh: The Botany, Culture, and Therapeutic Uses of the World's Two Most Important Resins