History of human rights

The history of human rights involves religious, cultural, philosophical and legal developments throughout recorded history.

While the modern human rights movement hugely expanded in post-World War II era,[1] the concept can be traced through all major religions, cultures and philosophies. Ancient Hindu law (Manu Smriti), Confucianism, the Qur'an and the Ten Commandments all outline some of the rights now included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The concept of natural law, guaranteeing natural rights despite varying human laws and customs, can be traced back to Ancient Greek philosophers, while Enlightenment philosophers suggest a social contract between the rulers and the ruled. The world's first Buddhist state in India, known as the Maurya Empire, established the world's first welfare system, including free hospitals and education. The African concept of ubuntu is a cultural view of what it is to be human. Modern human rights thinking is descended from these many traditions of human values and beliefs.[2]

Early history of human rights

Human rights in the ancient world

While it is known that the reforms of Urukagina of Lagash, the earliest known legal code (c. 2350 BC), must have addressed the concept of rights to some degree, the actual text of his decrees has not yet been found. The oldest legal codex extant today is the Neo-Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu (ca. 2050 BC). Several other sets of laws were also issued in Mesopotamia, including the Code of Hammurabi (ca. 1780 BC), one of the most famous examples of this type of document. It shows rules, and punishments if those rules are broken, on a variety of matters, including women's rights, men's rights, children's rights and slave rights.[3]

The prefaces of these codes invoked the Mesopotamian gods for divine sanction. Societies have often derived the origins of human rights in religious documents. The Vedas, the Bible, the Qur'an and the Analects of Confucius are also among the early written sources that address questions of people's duties, rights, and responsibilities.

The Persian Cyrus Cylinder is widely considered as "the world's first charter of human rights"[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] and it's linked to the repatriation of the Jews following their Babylonian captivity,[11] a deed which the Book of Ezra attributes to Cyrus the Great.[12][13].

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire of ancient India established unprecedented principles of civil rights in the 3rd century BC under Ashoka the Great. After his brutal conquest of Kalinga in circa 265 BC, he felt remorse for what he had done, and as a result, adopted Buddhism. From then, Ashoka, who had been described as "the cruel Ashoka" eventually came to be known as "the pious Ashoka". During his reign, he pursued an official policy of nonviolence (ahimsa) and the protection of human rights, as his chief concern was the happiness of his subjects.[14] The unnecessary slaughter or mutilation of animals was immediately abolished, such as sport hunting and branding. The first welfare state was established. Ashoka also showed mercy to those imprisoned, allowing them outside one day each year, and offered common citizens free education at universities. He treated his subjects as equals regardless of their religion, politics or caste, and constructed free hospitals for both humans and animals. Ashoka defined the main principles of nonviolence, tolerance of all sects and opinions, obedience to parents, respect for teachers and priests, being liberal towards friends, humane treatment of servants, and generosity towards all. These reforms are described in the Edicts of Ashoka.

In the Maurya Empire, citizens of all religions and ethnic groups also had rights to freedom, tolerance, and equality. The need for tolerance on an egalitarian basis can be found in the Edicts of Ashoka, which emphasize the importance of tolerance in public policy by the government. The slaughter or capture of prisoners of war was also condemned by Ashoka.[15] Some sources claim that slavery was also non-existent in ancient India.[16] Other state, however, that slavery existed in ancient India, where it is recorded in the Sanskrit Laws of Manu of the 1st century BC.[17]

Early Islamic Caliphate

Many reforms in human rights took place under Islam between 610 and 661, including the period of Muhammad's mission and the rule of the four immediate successors who established the Rashidun Caliphate. Historians generally agree that Muhammad preached against what he saw as the social evils of his day,[18] and that Islamic social reforms in areas such as social security, family structure, slavery, and the rights of women and ethnic minorities improved on what was present in existing Arab society at the time.[19][20][21][22][23][24] For example, according to Bernard Lewis, Islam "from the first denounced aristocratic privilege, rejected hierarchy, and adopted a formula of the career open to the talents."[19] John Esposito sees Muhammad as a reformer who condemned practices of the pagan Arabs such as female infanticide, exploitation of the poor, usury, murder, false contracts, and theft.[25] Bernard Lewis believes that the egalitarian nature of Islam "represented a very considerable advance on the practice of both the Greco-Roman and the ancient Persian world."[19] Muhammed also incorporated Arabic and Mosaic laws and customs of the time into his divine revelations.[26]

The Constitution of Medina, also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by Muhammad in 622. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib (later known as Medina), including Muslims, Jews, and pagans.[27][28] The document was drawn up with the explicit concern of bringing to an end the bitter inter tribal fighting between the clans of the Aws (Aus) and Khazraj within Medina. To this effect it instituted a number of rights and responsibilities for the Muslim, Jewish and pagan communities of Medina bringing them within the fold of one community-the Ummah.[29] The Constitution established the security of the community, freedom of religion, the role of Medina as a haram or sacred place (barring all violence and weapons), the security of women, stable tribal relations within Medina, a tax system for supporting the community in time of conflict, parameters for exogenous political alliances, a system for granting protection of individuals, a judicial system for resolving disputes, and also regulated the paying of blood-wite (the payment between families or tribes for the slaying of an individual in lieu of lex talionis).

Muhammad made it the responsibility of the Islamic government to provide food and clothing, on a reasonable basis, to captives, regardless of their religion. If the prisoners were in the custody of a person, then the responsibility was on the individual.[30] Lewis states that Islam brought two major changes to ancient slavery which were to have far-reaching consequences. "One of these was the presumption of freedom; the other, the ban on the enslavement of free persons except in strictly defined circumstances," Lewis continues. The position of the Arabian slave was "enormously improved": the Arabian slave "was now no longer merely a chattel but was also a human being with a certain religious and hence a social status and with certain quasi-legal rights."[31]

Esposito states that reforms in women's rights affected marriage, divorce, and inheritance.[25] Women were not accorded with such legal status in other cultures, including the West, until centuries later.[32] The Oxford Dictionary of Islam states that the general improvement of the status of Arab women included prohibition of female infanticide and recognizing women's full personhood.[33] "The dowry, previously regarded as a bride-price paid to the father, became a nuptial gift retained by the wife as part of her personal property."[25][34] Under Islamic law, marriage was no longer viewed as a "status" but rather as a "contract", in which the woman's consent was imperative.[25][33][34] "Women were given inheritance rights in a patriarchal society that had previously restricted inheritance to male relatives."[25] Annemarie Schimmel states that "compared to the pre-Islamic position of women, Islamic legislation meant an enormous progress; the woman has the right, at least according to the letter of the law, to administer the wealth she has brought into the family or has earned by her own work."[35] William Montgomery Watt states that Muhammad, in the historical context of his time, can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women’s rights and improved things considerably. Watt explains: "At the time Islam began, the conditions of women were terrible - they had no right to own property, were supposed to be the property of the man, and if the man died everything went to his sons." Muhammad, however, by "instituting rights of property ownership, inheritance, education and divorce, gave women certain basic safeguards."[36] Haddad and Esposito state that "Muhammad granted women rights and privileges in the sphere of family life, marriage, education, and economic endeavors, rights that help improve women's status in society."[37] However, other writers have argued that women before Islam were more liberated drawing most often on the first marriage of Muhammad and that of Muhammad's parents, but also on other points such as worship of female idols at Mecca.[38]

Sociologist Robert Bellah (Beyond belief) argues that Islam in its seventh-century origins was, for its time and place, "remarkably modern...in the high degree of commitment, involvement, and participation expected from the rank-and-file members of the community." This is because, he argues, that Islam emphasized the equality of all Muslims, where leadership positions were open to all. Dale Eickelman writes that Bellah suggests "the early Islamic community placed a particular value on individuals, as opposed to collective or group responsibility."[39]

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter originally issued in 1215. Magna Carta was the most significant early influence on the extensive historical process that led to the rule of constitutional law today. Magna Carta influenced the development of the common law and many constitutional documents, such as the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Magna Carta was originally written because of disagreements amongst Pope Innocent III, King John and the English barons about the rights of the King. Magna Carta required the King to renounce certain rights, respect certain legal procedures and accept that his will could be bound by the law. It explicitly protected certain rights of the King's subjects, whether free or fettered — most notably the writ of habeas corpus, allowing appeal against unlawful imprisonment.

For modern times, the most enduring legacy of Magna Carta is considered the right of habeas corpus. This right arises from what are now known as clauses 36, 38, 39, and 40 of the 1215 Magna Carta. The Magna Carta also included the right to due process:

No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.

— Clause XXIX of the Magna Carta

Modern human rights movement

The conquest of the Americas in the 16th century by the Spanish resulted in vigorous debate about human rights in Spain. The debate from 1550-51 between Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda at Valladolid was probably the first on the topic of human rights in European history. Several 17th and 18th century European philosophers, most notably John Locke, developed the concept of natural rights, the notion that people are naturally free and equal.[40][41] Though Locke believed natural rights were derived from divinity since humans were creations of God, his ideas were important in the development of the modern notion of rights. Lockean natural rights did not rely on citizenship nor any law of the state, nor were they necessarily limited to one particular ethnic, cultural or religious group.

Two major revolutions occurred that century in the United States (1776) and in France (1789). The Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776 sets up a number of fundamental rights and freedoms. The later United States Declaration of Independence includes concepts of natural rights and famously states "that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Similarly, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen defines a set of individual and collective rights of the people. These are, in the document, held to be universal - not only to French citizens but to all men without exception.

1800AD to World War I

Philosophers such as Thomas Paine, John Stuart Mill and Hegel expanded on the theme of universality during the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1831 William Lloyd Garrison wrote in a newspaper called The Liberator that he was trying to enlist his readers in "the great cause of human rights"[42] so the term human rights probably came into use sometime between Paine's The Rights of Man and Garrison's publication. In 1849 a contemporary, Henry David Thoreau, wrote about human rights in his treatise On the Duty of Civil Disobedience [1] which was later influential on human rights and civil rights thinkers. United States Supreme Court Justice David Davis, in his 1867 opinion for Ex Parte Milligan, wrote "By the protection of the law, human rights are secured; withdraw that protection and they are at the mercy of wicked rulers or the clamor of an excited people."[43]

Many groups and movements have managed to achieve profound social changes over the course of the 20th century in the name of human rights. In Western Europe and North America, labour unions brought about laws granting workers the right to strike, establishing minimum work conditions and forbidding or regulating child labour. The women's rights movement succeeded in gaining for many women the right to vote. National liberation movements in many countries succeeded in driving out colonial powers. One of the most influential was Mahatma Gandhi's movement to free his native India from British rule. Movements by long-oppressed racial and religious minorities succeeded in many parts of the world, among them the civil rights movement, and more recent diverse identity politics movements, on behalf of women and minorities in the United States.

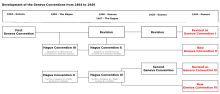

The foundation of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the 1864 Lieber Code and the first of the Geneva Conventions in 1864 laid the foundations of International humanitarian law, to be further developed following the two World Wars.

Between World War I and World War II

The League of Nations was established in 1919 at the negotiations over the Treaty of Versailles following the end of World War I. The League's goals included disarmament, preventing war through collective security, settling disputes between countries through negotiation, diplomacy and improving global welfare. Enshrined in its Charter was a mandate to promote many of the rights which were later included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The League of Nations had mandates to support many of the former colonies of the Western European colonial powers during their transition from colony to independent state.

Established as an agency of the League of Nations, and now part of United Nations, the International Labour Organization also had a mandate to promote and safeguard certain of the rights later included in the UDHR:

the primary goal of the ILO today is to promote opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work, in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity.

— Report by the Director General for the International Labour Conference 87th Session

After World War II

Rights in War and the Geneva Conventions

The Geneva Conventions came into being between 1864 and 1949 as a result of efforts by Henry Dunant, the founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The conventions safeguard the human rights of individuals involved in conflict, and follow on from the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions, the international community's first attempt to define laws of war. Despite first being framed before World War II, the conventions were revised as a result of World War II and readopted by the international community in 1949.

The Geneva Conventions are:

- First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" (first adopted in 1864, last revision in 1949)

- Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" (first adopted in 1949, successor of the 1907 Hague Convention X)

- Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" (first adopted in 1929, last revision in 1949)

- Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War" (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the 1907 Hague Convention IV)

In addition, there are three additional amendment protocols to the Geneva Convention:

- Protocol I (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 it had been ratified by 167 countries.

- Protocol II (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 it had been ratified by 163 countries.

- Protocol III (2005): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem. As of May 20, 2008, it had been ratified by 28 countries and signed but not yet ratified by an additional 59 countries

All four conventions were last revised and ratified in 1949, based on previous revisions and partly on some of the 1907 Hague Conventions. Later conferences have added provisions prohibiting certain methods of warfare and addressing issues of civil wars. Nearly all 200 countries of the world are "signatory" nations, in that they have ratified these conventions. The International Committee of the Red Cross is the controlling body of the Geneva conventions (see below).

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a non-binding declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly[45] in 1948, partly in response to the barbarism of World War II. The UDHR urges member nations to promote a number of human, civil, economic and social rights, asserting these rights are part of the "foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world". The declaration was the first international legal effort to limit the behavior of states and press upon them duties to their citizens following the model of the rights-duty duality.

...recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world

— Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

The UDHR was framed by members of the Human Rights Commission, with Eleanor Roosevelt as Chair, who began to discuss an International Bill of Rights in 1947. The members of the Commission did not immediately agree on the form of such a bill of rights, and whether, or how, it should be enforced. The Commission proceeded to frame the UDHR and accompanying treaties, but the UDHR quickly became the priority.[46] Canadian law professor John Humphrey and French lawyer Rene Cassin were responsible for much of the cross-national research and the structure of the document respectively, where the articles of the declaration were interpretative of the general principle of the preamble. The document was structured by Cassin to include the basic principles of dignity, liberty, equality and brotherhood in the first two articles, followed successively by rights pertaining to individuals; rights of individuals in relation to each other and to groups; spiritual, public and political rights; and economic, social and cultural rights. The final three articles place, according to Cassin, rights in the context of limits, duties and the social and political order in which they are to be realized.[46] Humphrey and Cassin intended the rights in the UDHR to be legally enforceable through some means, as is reflected in the third clause of the preamble:[46]

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law.

— Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

Some of the UDHR was researched and written by a committee of international experts on human rights, including representatives from all continents and all major religions, and drawing on consultation with leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi.[47] The inclusion of both civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights[46][48] was predicated on the assumption that basic human rights are indivisible and that the different types of rights listed are inextricably linked. Though this principle was not opposed by any member states at the time of adoption (the declaration was adopted unanimously, with the abstention of the Soviet bloc, Apartheid South Africa and Saudi Arabia), this principle was later subject to significant challenges.[48]

Notes

- ^ Incorporating Human Rights into the College Curriculum.

- ^ Ball, Gready (2007) p.14

- ^ Code of Hammurabi

- ^ "The First Global Statement of the Inherent Dignity and Equality". United Nations. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ^ Farrokh, Kaveh (2007). "Cyrus the Great and early Achaemenids". Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781846031083.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). "Philosophical Visions: Human Nature, Natural Law, and Natural Rights". The Evolution of International Human Rights: Visions Seen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 081221854X.

- ^ Robertson, Arthur Henry; Merrills, J. G. (1996). Human rights in the world : an introduction to the study of the international protection of human rights. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719049231.

- ^ Hedrick, Larry (2007). Xenophon's Cyrus the Great: The Arts of Leadership and War. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312364695.

- ^ Woods, Michael; Woods, Mary B. (2009). Seven Wonders of the Ancient Middle East. Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 9780822575733.

- ^ Abtahi, Hirad (2006). Abtahi, Hirad; Boas, Gideon (eds.). The Dynamics of International Criminal Justice: Essays in Honour of Sir Richard May. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004145877.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

BM-CCwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Free, Joseph P.; Vos, Howard Frederic (1992). Vos, Howard Frederic (ed.). Archaeology and Bible history. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 9780310479611.

- ^ Becking, Bob (2006). ""We All Returned as One!": Critical Notes on the Myth of the Mass Return". In Lipschitz, Oded; Oeming, Manfred (eds.). Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061047.

- ^ Chauhan, O.P. (2004).

- ^ Amartya Sen (1997)

- ^ Arrian, Indica, "This also is remarkable in India, that all Indians are free, and no Indian at all is a slave. In this the Indians agree with the Lacedaemonians. Yet the Lacedaemonians have Helots for slaves, who perform the duties of slaves; but the Indians have no slaves at all, much less is any Indian a whore."

- ^ Slave-owning societies, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Alexander (1998), p.452

- ^ a b c Lewis (1998) Cite error: The named reference "LewisNYRB" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Watt (1974), p.234

- ^ Robinson (2004) p.21

- ^ Haddad, Esposito (1998), p. 98

- ^ "Ak̲h̲lāḳ", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ^ Joseph, Najmabadi (2007). Chapter: p.293. Gallagher, Nancy. Infanticide and Abandonment of Female Children

- ^ a b c d e Esposito (2005) p. 79

- ^ Ahmed I. (1996). WESTERN AND MUSLIM PERCEPTIONS OF UNIVERSAL HUMAN RIGHTS. Afrika Focus.

- ^ See:

- Firestone (1999) p. 118;

- "Muhammad", Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Watt. Muhammad at Medina and R. B. Serjeant "The Constitution of Medina." Islamic Quarterly 8 (1964) p.4.

- ^ R. B. Serjeant, The Sunnah Jami'ah, pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrim of Yathrib: Analysis and translation of the documents comprised in the so-called "Constitution of Medina." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 41, No. 1. 1978), page 4.

- ^ Maududi (1967), Introduction of Ad-Dahr, "Period of revelation", pg. 159

- ^ Lewis (1994) chapter 1

- ^ Jones, Lindsay. p.6224

- ^ a b Esposito (2004), p. 339

- ^ a b Khadduri (1978)

- ^ Schimmel (1992) p.65

- ^ Maan, McIntosh (1999)

- ^ Haddad, Esposito (1998) p.163

- ^ Turner, Brian S. Islam (ISBN 041512347X). Routledge: 2003, p77-78.

- ^ McAuliffe (2005) vol. 5, pp. 66-76. “Social Sciences and the Qur’an”

- ^ Locke's Political Philosophy (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^ Locke's Political Philosophy (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^ Mayer (2000) p. 110

- ^ "Ex Parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2, 119. (full text)" (PDF). December 1866. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ^ Eleanor Roosevelt: Address to the United Nations General Assembly 10 December 1948 in Paris, France

- ^ (A/RES/217, 1948-12-10 at Palais de Chaillot, Paris)

- ^ a b c d Glendon, Mary Ann (July 2004). "The Rule of Law in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights". Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights. 2 (5).

- ^ Glendon (2001)

- ^ a b Ball, Gready (2007) p.34