Sodium oxybate

It has been suggested that this article be merged into gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid. (Discuss) Proposed since September 2010. |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.231 |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

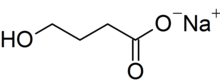

| C4H7NaO3 | |

| Molar mass | 126.087 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Xyrem (sodium oxybate) is a prescription medication manufactured by Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cataplexy associated with narcolepsy [1] and Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (EDS) associated with narcolepsy.[2] Sodium oxybate is the sodium salt of γ-hydroxybutyric acid.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommends Xyrem as a standard of care for the treatment of cataplexy, daytime sleepiness, and disrupted sleep due to narcolepsy in its Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Narcolepsy and other Hypersomnias of Central Origin. These recommendations are based upon careful review of the medical literature, and the designation “standard” of care “reflects a high degree of clinical certainty” based on strong empirical evidence.[3]

Xyrem is a prescription medication used to treat narcolepsy, which is a rare medical condition that has been documented worldwide, with a prevalence ranging from 0.002% in Israel to 0.18% in Japan. Prevalence in the US is approximately 0.05%. The pentad of clinical symptoms includes: Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (EDS), cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucinations, sleep paralysis, and fragmented sleep. EDS and cataplexy are the most common daytime symptoms of narcolepsy.[4]

Development

Xyrem is designated as an orphan drug, which is a pharmaceutical agent that has been developed specifically to treat a rare medical condition, the condition itself being referred to as an orphan disease. The assignment of orphan status to a disease and to any drugs developed to treat it is a matter of public policy in many countries, and has resulted in medical breakthroughs that may not have otherwise been achieved due to the economics of drug research and development.[5] In the last 20 years efforts have been made to encourage companies to develop orphan drugs. The Orphan Drug Act in the US (1983) was succeeded by similar legislation in Japan (1985), Australia (1997), and the European Community (2000).[6]

The development of Xyrem (sodium oxybate) oral solution as a prescription medication was initiated by the Office of Orphan Products Development (OOPD).[7] The OOPD is a department of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) dedicated to promoting the development of products that demonstrate promise for the diagnosis and/or treatment of rare diseases or conditions.[8]

- In 1994, the OOPD petitioned a pharmaceutical company called Orphan Medical to investigate sodium oxybate as a potential treatment for narcolepsy.[7]

- In 1996, Orphan Medical submitted an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) to the FDA and began Phase I, II, and III clinical trials to investigate the safety and efficacy of sodium oxybate.[7]

- In 2000, Orphan Medical submitted a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA for Xyrem.[7] Xyrem was granted "Priority Review",[7] which is an expedited review process given to products that offer a major advance in treatment or treatment where no adequate therapy exists.[9]

- In 2002, Xyrem received approval from the FDA for the treatment of cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy.[1]

- In 2005, Xyrem was acquired by Jazz Pharmaceuticals when they purchased Orphan Medical. Later that year Xyrem was granted a second indication by the FDA for the treatment of EDS in patients with narcolepsy.[2] Also that year Xyrem was approved for the treatment of cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy by Health Canada’s Therapeutic Products Directorate, and for the treatment of cataplexy in adult patients with narcolepsy by the European Medicines Agency for the European Union (EU) and the Swiss Agency, Swissmedic, for Therapeutic Products.[4]

- In 2006, Xyrem received an expanded indication for narcolepsy with cataplexy in the EU.[4]

- In 2010, Jazz Pharmaceuticals completed two Phase III clinical trials investigating sodium oxybate for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia is a complex musculoskeletal disorder clinically characterized by widespread pain usually accompanied by fatigue, insomnia, and dyscognition. The company submitted a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA and a formal response is expected in 2010.[10]

There are also ongoing tests to see if Xyrem could prove helpful with other medical conditions, such as Parkinson's, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME), and Schizophrenia.[11]

Cost

Orphan drugs by their nature are very specialized and have relatively few patients to spread the costs associated with bringing them to market. The average cost a specialty drug in the US is $2,875 per month or $34,500 annually[12] however drug prices vary by country.

In European Union (EU) countries, the government either provides national health insurance (as in the UK and Italy) or strictly regulates quasi-private social insurance funds (as in Germany, France, and the Netherlands). These government agencies are the sole purchaser (or regulator) of medical goods and services and have the power to set prices.[13]The cost of pharmaceuticals, including Xyrem, tend to be lower in these countries.[14]

In the US, the cost of Xyrem is $800 (180 mL bottle, 500 mg/mL)[15] and the effective dose range is 6 to 9 grams per night which equates to $1,600 - $2,400 per month. Xyrem is covered by most insurance plans including Medicare and Medicaid and approximately 90% of Xyrem patients have a flat monthly co-pay. 75% of Xyrem insurance copays are less than $50 and 42% are less than $25 for a one month supply. The manufacturer offers a coupon program for the small number of patients with larger copays. Some insurance companies may require physicians to fill out an insurance form called a Prior Authorization as part of the prescribing process. Additionally, the manufacturer offers a Patient Assistance Program to patients that do not have insurance and are unable to afford their Xyrem prescription. Approximately 8% of Xyrem patients currently participate in this program and receive their prescription for free.[16]

Existing US Patents on Xyrem prevent other companies from manufacturing it as a drug. Xyrem is protected by US Patients 6472431,[17] and 6780889[18] which are set to expire in 2019 and 2022, respectively.

Distribution

A number of measures have been put in place by Xyrem's manufacture to ensure that it is used safely and appropriately. Xyrem requires a prescription and can only be obtained through a restricted distribution program, called the "Xyrem Success Program". This restricted distribution program is required by the FDA as part of a Risk Management Program (RMP) to manage product safety and prevent abuse.[19]

The program involves many risk management components, such as:

- Physician education

- Registration

- Patient education

- Detailed patient surveillance

The program includes a single centralized pharmacy with a toll-free number.

Initial dosages are set by the prescribing physician. Each bottle of Xyrem is shipped with a graduated syringe (measured in grams) and two dosing cups. Each night, the patient mixes two doses with 60ml of water (sometimes substituted with a calorie-free beverage to cover the unpleasant taste of the medication). The first dose is taken at bedtime, and the second is taken 2.5 to 4 hours later.

Use by athletes

Xyrem has been instrumental in allowing cyclist Franck Bouyer to resume his career and is the only treatment for narcolepsy approved by the World Anti-Doping Agency.[20]

Safety

Xyrem has been safely used by patients with narcolepsy for more than seven years.[4] A recent analysis evaluated the postmarketing safety of Xyrem (Wang et al. 2009), including rates of abuse, dependence, and withdrawal, using a conservative application of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria to all worldwide Xyrem adverse event cases containing reporting terminology related to abuse or misuse.[4] The analysis included cases reported to the manufacture from market introduction in 2002 through March 2008. Using the DSM-IV criteria, the analysis found the following rates of abuse, dependence, and withdrawal of the approximately 26,000 patients who used Xyrem during this period:

- Abuse—10 cases (0.04%)

- Dependence—4 cases (0.016%)

- Withdrawal symptoms after discontinuation—8 cases (0.031%; including 3 of the previous 4 dependence cases)

The analysis also found 2 confirmed cases (0.008%) of sodium oxybate–facilitated sexual assault; in both cases the women knew that they were taking sodium oxybate. In addition, there were 21 deaths (0.08%) in patients receiving sodium oxybate treatment, with 1 death known to be related to sodium oxybate, and 3 cases (0.01%) of traffic accidents involving drivers taking sodium oxybate. The extremely low rates of abuse, dependence, withdrawal, and assault found in this analysis suggest that after seven years of commercial availability, Xyrem use is largely appropriate and confined to patients with legitimate therapeutic needs.[4]

In the US, Xyrem is classified as a Schedule III controlled substance for medicinal use under the Controlled Substances Act, with illicit use subject to Schedule I penalties. Examples of other schedule III products in the US include vicodin, tylenol with codeine, and testosterone.[21] In Canada and the European Union (EU), it is classified as a Schedule III and a Schedule IV controlled substance, respectively.[4]

See also

References

- ^ a b "FDA Approval Letter for Xyrem; Indication: Cataplexy associated with narcolepsy" (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. 2002-07-17. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ a b "FDA Approval Letter for Xyrem; Indication: EDS (Excessive Daytime Sleepiness) associated with narcolepsy" (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. 2005-11-18. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ Morgenthaler, TI; Kapur, VK; Brown, T; Swick, TJ; Alessi, C; Aurora, RN; Boehlecke, B; Chesson Jr, AL; Friedman, L (2007). "Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin". Sleep. 30 (12): 1705–11. PMC 2276123. PMID 18246980.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Wang YG, Swick TJ, Carter LP, Thorpy MJ, Benowitz NL (2009). "Safety overview of postmarketing and clinical experience of sodium oxybate (Xyrem): abuse, misuse, dependence, and diversion". J Clin Sleep Med. 5 (4): 365–71. PMC 2725257. PMID 19968016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Office of Inspector General (2001-05). "The Orphan Drug Act Implementation and Impact" (PDF). US Department of Health and Human Services.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ J K Aronson, Chairman of the Editorial Board, British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2006 March; 61(3): 243–245). "Rare diseases and orphan drugs". Br J Clin Pharmacol.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Learn About XYREM®". Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ "Office of Orphan Products Development". US Food and Drug Administration. 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ "Fast Track, Accelerated Approval and Priority Review". US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ "Jazz Pharmaceuticals Submits New Drug Application for JZP-6 (sodium oxybate) for the Treatment of Fibromyalgia /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ --". Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. & PR Newswire. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ "Search of: xyrem". ClinicalTrials.gov. US National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ "Rx Watchdog Report: Brand Name Drug Prices Continue to Climb Despite Low General Inflation Rate" (PDF). AARP. 2010-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Patricia M. Danzon is the Celia Z. Moh Professor of Health Care Systems, Insurance, and Risk Management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. "Making Sense of Drug Prices" (PDF). Regulation Volume 23, No. 1. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Patricia M. Danzon is the Celia Z. Moh Professor of Health Care Systems, Insurance, and Risk Management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. "Making Sense of Drug Prices" (PDF). Regulation Volume 23, No. 1. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "PricePoint Rx". First DataBank. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ "Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Q1 2010 Earnings Call Transcript". Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ US patent 6472431, Cook H, Hamilton M, Danielson D, Goderstad C, Reardan D, "Microbiologically sound and stable solutions of gamma-hydroxybutyrate salt", issued 2002-10-29, assigned to Orphan Medical, Inc.

- ^ US patent 6780889, Cook H, Hamilton M, Danielson D, Goderstad C, Reardan D, "Microbiologically sound and stable solutions of gamma-hydroxybutyrate salt", issued 2004-08-24, assigned to Orphan Medical, Inc.

- ^ "Approval Letter for Xyrem (sodium oxybate) oral solution; Risk Management Program(RMP)Requirements" (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. 2002-07-17.

- ^ Bouygues (25 Jan. 2009) Bouyer : "Une nouvelle expérience"(in French.) Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ "Drug Scheduling". US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Retrieved 2010-10-03.

Further reading

- Laborit, H (1964). "Sodium 4-hydroxybutyrate". Neuropharmacology. 3: 433–51. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(64)90074-7. PMID 14334876.

External links

- Xyrem Official Website Jazz Pharmaceuticals

- Xyrem Package Insert

- WebMD - Xyrem