Aftermath of World War II

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Template:WorldWarIISegmentUnderInfoBox

The aftermath of World War II introduced a new era of tensions arising from opposing ideologies, mutual distrust, and a nuclear arms race between East and West, together with a radically altered international correlation of forces. There were post-war boundary disputes in Europe and elsewhere, and questions of national self determination in Poland and in European colonial territories abroad.

The immediate post-war period in Europe was characterised by the Soviet Union annexing or converting into Soviet Socialist Republics[1][2][3] all the countries that the Red Army had liberated behind its own lines in driving the German invaders out of central and eastern Europe. Countries converted into Soviet Satellite states within the Eastern Bloc were: People's Republic of Poland; People's Republic of Bulgaria; People's Republic of Hungary;[4] Czechoslovak Socialist Republic;[5] People's Republic of Romania;[6][7] People's Republic of Albania;[8] All these countries, with the exception only of Poland, had provided troops to fight alongside the Germans during the war. The German Democratic Republic or communist East Germany was created from the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany.,[9] while the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia emerged as an independent communist state not aligned with the USSR.

In Japan, survivors of the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, known as hibakusha (被爆者) were ostracized by Japanese society. Japan provided no special assistance to these people until 1952.[10] By the 65th anniversary of the bombings, total casualties from the initial attack and later deaths reached about 270,000 in Hiroshima.[11] and 150,000 in Nagasaki.[12] About 230,000 hibakusha are still alive,[11] about 2200 of whom are suffering from radiation-caused illnesses.[13]

Japan was occupied by the US, aided by Commonwealth troops. In accordance with the Potsdam Conference agreements, which promised territorial concessions to the USSR in the Far East in return for entering the war against Japan, the USSR occupied and subsequently annexed the strategic island of Sakhalin. During the occupation of Japan, the focus would be on demilitarisation of the nation, demolition of the Japanese arms industry, and the installation of a democratic government with a new constitution. The Far Eastern Commission and Allied Council For Japan were established to administer the occupation of Japan. These bodies served a similar function to the Allied Control Council in occupied Germany.

A World in Ruins

At the end of the war, millions of people were homeless, the European economy had collapsed, and much of the European industrial infrastructure was destroyed. The Soviet Union had been heavily affected, with 30% of its economy destroyed.

Luftwaffe bombings of Frampol, Wieluń and Warsaw in 1939 instituted the practice of bombing purely civilian targets. Many other cities suffered similar annihilation as this practice was continued by both the Allies and Axis forces.

The United Kingdom ended the war economically exhausted by the war effort. The wartime coalition government was dissolved; new elections were held, and Winston Churchill was defeated in a landslide general election by the Labour Party under Clement Attlee.

In 1947, United States Secretary of State George Marshall devised the "European Recovery Program", better known as the Marshall Plan, effective in the years 1948 - 1952. It allocated US$13 billion for the reconstruction of Western Europe.

Soviet Union after the war

The losses suffered by the Soviet Union in the war against Germany were enormous. Total demographic population loss was about 40 million people, of which 8.7 million were combat deaths.[14] The non-military deaths of approximately 19 million included deaths by starvation in the siege of Leningrad; deaths in German prisons and concentration camps; deaths from mass shootings of civilians; deaths of labourers in German industry; deaths from famine and disease; deaths in Soviet camps; and the deaths of both Soviet non-conscript partisans and of Soviet citizens not conscripted into the Soviet armed forces who died in German or German-controlled military units fighting the USSR.[15] It would take 30 years for the post-war population level to catch up with pre-war level.[16] Soviet ex-POWs and civilians repatriated from abroad were suspected of having been Nazi collaborators, and 226,127 of them were sent to forced labour camps after scrutiny by Russian intelligence, NKVD. Many ex-POWs and young civilians were also conscripted to serve in the Red Army, others worked in labour battalions to rebuilt infrastructure destroyed during the war.[17][18] Although the Soviet Union was victorious in World War II, its economy had been devastated. Roughly a quarter of the country's capital resources were destroyed, and industrial and agricultural output in 1945 fell far short of prewar levels. To help rebuild the country, the Soviet government obtained limited credits from Britain and Sweden but refused assistance proposed by the United States under the economic aid programme known as the Marshall Plan. Instead, the Soviet Union compelled Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe to supply machinery and raw materials. Germany and former Nazi satellites including Finland made reparations to the Soviet Union. The reconstruction programme emphasised heavy industry, to the detriment of agriculture and consumer goods. By 1953, steel production was twice its 1940 level, but the production of many consumer goods and foodstuffs was lower than it had been in the late 1920s.[19]

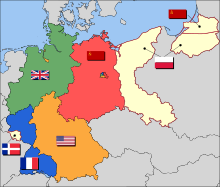

Germany after the war

Following the surrender of Germany, the country was partitioned into four zones of occupation, coordinated by the Allied Control Council. On January 1, 1947, the British and American forces merged their respective zones of occupation in Berlin into a single unified zone, handing over much of the administrative responsibility for running it to Germans under British and American supervision. Plans were made at the same time for the economic merger of the French zone of occupation to produce a federated West Germany. The planned merger was strongly opposed by the Soviet Union, which saw in these developments the precursor to the establishment of a separatist German government in occupied Germany, raising the prospect of communist authority being challenged from deep within the Soviet Zone.[20] It had been earlier agreed at Yalta between Britain, America and the Soviet Union that a defeated Germany would be ruled by a four-power Allied Control Council including the Soviet Union. With Britain, France and America having now entered into a separate agreement between themselves, the Allied Control Council had in effect ceased to exist as an organ of government. In mid-June 1948 the Soviet Union retaliated when the West substituted the Reichsmark as the official currency in West Germany with a new currency, the Deutsche Mark, printed in America.[21] In mid-1948, the Soviet Union blocked all passenger road and rail traffic between the Western zones and Berlin. Patrols of Russian and East German frontier guards were greatly increased in strength along the entire length of the Soviet zonal border. More than two million inhabitants of the British, French and American zones of Berlin were cut off from contact with the West. The Russians also imposed major electricity cuts. On June 26, 1948, the commander of the US Air Forces in Europe ordered an airlift to begin. Hundreds of transport aircraft from the West brought more than half a million tons of food to Berlin in the course of more than 550,000 sorties over the next 13 months. On May 12, 1949, after diplomatic negotiations, the Soviet Union finally lifted the Berlin blockade.[22] The Federal Republic of Germany was created out of the Western zones a few days later, The Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic. In the west, Alsace-Lorraine was returned to France, and the Saar area was separated from Germany and put in economic union with France. Austria was separated from Germany and divided into four zones of occupation, which reunited in 1955 to become the Republic of Austria.

Germany paid reparations to the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union mainly in the form of dismantled factories, forced labor, and coal. Germany was to be reduced to the standard of living she had at the height of the Great Depression.[23] Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years, the US and Britain pursued an "intellectual reparations" programme to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. The value of these amounted to around US$10 billion, equivalent to about US$100 billion in 2006 terms.[24] In accordance with the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947, payment of reparations was assessed from the countries of Italy, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Finland.

US policy in post-war Germany from April 1945 until July 1947 had been that no help should be given to the Germans in rebuilding their nation, save for the minimum required to mitigate starvation. The Allies' immediate post-war "industrial disarmament" plan for Germany had been to destroy Germany's capability to wage war by complete or partial de-industrialization. The first industrial plan for Germany, signed in 1946, required the destruction of 1,500 manufacturing plants. The purpose of this was to lower German heavy industry output to roughly 50% of its 1938 level. Dismantling of West German industry ended in 1951. By 1950, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants, and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons.[25] After lobbying by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Generals Clay and George Marshall, the Truman administration accepted that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base on which it had previously had been dependent.[26] In July 1947, President Truman rescinded on "national security grounds"[27] the directive that had ordered the US occupation forces to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany." A new directive recognised that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany."[28]

Population Displacement

As a result of the new borders drawn by the victorious nations, large populations suddenly found themselves in hostile territory. The Soviet Union took over areas formerly controlled by Germany, Finland, Poland, and Japan. Poland received most of Germany east of the Oder-Neisse line, including the industrial regions of Silesia. The German state of the Saar was temporarily a protectorate of France but later returned to German administration. The number of Germans expelled, as set forth at Potsdam, totalled roughly 12 million, including 7 million from Germany proper and 3.0 million from the Sudetenland. Mainstream estimates of casualties from the expulsions range between 500,000 - 2 million dead.

In Eastern Europe, two million Poles were expelled by the Soviet Union from east of the new border which approximated the Curzon Line. This border change reversed the results of the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War. Former Polish cities such as L'vov came under control of the Soviet administration of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Rape during the occupation of Germany and Japan

The official policy of the German Democratic Republic was that they were liberated, not occupied by the Russians.[29] Official Soviet policy denied more than “isolated excesses” by Russian troops occurred.[30] Until the reunification of Germany, GDR histories virtually ignored the actions of Russian troops, and Russian histories still tend to do so.[31] Reports of mass rapes by Russian troops were often dismissed as anti-Communist propaganda or the normal byproduct of war.[32]

Civilian populations in Romania and Hungary were raped and robbed by Russian troops.[33] Mass rapes followed the fall of Budapest in February 1945.[34] Even the Swedish legation was attacked.[35] The population of Bulgaria was largely spared this, due to the generally excellent behavior of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin’s troops.[36] Marshall Rodion Malinovsky’s troops “left a trail of rape and murder from Budapest to Pilsen”.[37]

When Milovan Djilas complained about rape and looting by Russian troops in Yugoslavia, Stalin replied, saying “Can’t he understand it if a soldier who has crossed thousands of kilometers through blood and fire and death has fun with a woman or takes some trifle?”[38] Other Russian allies also vainly protested the actions of Russian troops.[39] Over 4.5 million Germans fled towards the West.[40]

The population of Germany was treated significantly worse those of Hungary and Romania.[41] Rape and murder of German civilians was as bad as, and sometimes worse than Nazi propaganda had expected it to be.[42][43] Political officers encouraged Russian troops to seek revenge and terrorize the German population.[44] In front-line newspapers, journalist Ilya Ehrenburg encouraged Russian troops to murder Germans and burn down their homes.[45] In January 1945, Marshal Zhukov orders stated “We will get our terrible revenge for everything”.[46] Russian troops were informed about the concentration camps and told the victims were Russian citizens.[47] As the troops approached Berlin, Stalin sent a mixed message; he discouraged mistreating German civilians, yet denied that Soviet troops had done so.[48]

When the Russian army invaded Germany in the spring of 1945, large numbers of the troops raped and robbed the Germans.[49] Many units, especially in the second wave engaged in frequent rape, murder, and robbery.[50][51] In East Prussia, Russian troops would often rape every German female over the age of about twelve, killing many, loot the village, and then set it on fire.[52] Many German women committed suicide.[53] When the Russians invaded Silesia, they engaged in mass rape of German and Polish women.[54]

Unlike the Western Zones, rape was common in the Soviet Occupied Zone and fear of rape was universal.[55][56][57][58] The worst days were during the mass rapes of April 24 to May 5, 1945.[59] Estimates of the numbers of rapes committed by Soviet soldiers range from tens of thousands to 2 million.[60][61][62] About one-third of all German women in Berlin were raped by Soviet forces.[63] A substantial minority were raped multiple times.[64][65] In Berlin, contemporary hospital records indicate between 95,000 and 130,000 women were raped by Russian troops.[66] About 10,000 of these women died, mostly by suicide.[67][68]

Marshal Vasily Sokolovsky was more concerned with the spread of venereal disease among his troops than their raping German women.[69] German Communist Party activists lodged protests and tried to obtain weapons to protect themselves from constant rape and robbery by Russian troops.[70] Jewish and anti-Communist women had to flee from their Russian “liberators”.[71]In October 1945, the Vatican representative in Berlin claimed women from ages 10 to 75 had been raped by the Russians and 80% of the women had become infected with venereal disease.[72] Women were publicly gang raped, mutilated, and murdered.[73] Not all Russian soldiers behaved this way, there were also examples kindness, especially towards children.[74]

Hundreds of local commandants were placed in charge of the Russian Occupied Zone.[75] Punishment for rape and robbery varied depending on the individual commandant.[76] Some punished murder, rape, and robbery severely; many didn’t even bother to report it.[77] Freed Russian POWs and forced laborers also raped and robbed many German civilians.[78] Members of the NKVD also raped and brutalized German civilians.[79]

Syphilis spread rapidly in the Soviet occupation zone, due to in a large part to rapes committed by Soviet soldiers.[80] Formal prostitution and desperate women willing to exchange sex for food also contributed to the spread of venereal disease.[81] Many doctors in Berlin, supported by the Protestant bishop, ignored the law to perform requested abortions on rape victims.[82]

Russian military police did little to stop murder, rape, and robbery by Russian troops.[83] German police were largely ineffective; they were heavily outgunned and intervened at risk of their own lives.[84] When the German police did make arrests, the Russian commandants frequently did not prosecute the Russian soldiers and the German policemen were sometimes arrested by the NKVD.[85] In Frankfort, tanks sometimes had to be brought in to suppress out of control Russian troops.[86]

Stalin and Beria received detailed reports of the troops’ behavior.[87] Foreign reports of Soviet brutality were denounced as false.[88] Rape, robbery, and murder were blamed on German bandits impersonating Russian soldiers.[89] Some justified Russian troops brutality towards German civilians based on previous brutality of German troops towards Russian civilians.[90]

The problem of rape in the Soviet Zone became worse summer of 1946, but improved in 1947.[91] German women faced a persistent threat of rape from Russian soldiers until the winter of 1947-48, when the Soviet troops were finally confined to strictly guarded camps and posts.[92] These rapes turned many potential sympathizers against the Soviet Union, while the behavior of US troops led to many Germans wanting “the American way of life”.[93]

Rapes also occurred under other occupation forces, though the majority were committed by Russian troops.[94] French Moroccan troops matched the behavior of Soviet troops when it came to rape, especially in the early occupations of Baden and Württemberg.[95] In a letter to the editor published in September 1945, American army sergeant wrote "Our own Army and the British Army along with ours have done their share of looting and raping ... This offensive attitude among our troops is not at all general, but the percentage is large enough to have given our Army a pretty black name, and we too are considered an army of rapists."[96] Robert Lilly’s analysis of military records led him to conclude about 14,000 rapes occurred in Britain, France and Germany at the hands of US soldiers between 1942 to 1945.[97] Lilly assumed that only 5% of rapes by American soldiers were reported, while other analysts concluded 50% of the rapes were reported.[98]

Prostitution and “semi-prostitution” were common in all of the Occupied Zones.[99] Material need and desire for companionship led to many German women engaging in sexual relationships with soldiers of the Occupation forces.[100] Others formed liaisons with occupation soldiers to protect themselves from rape.[101] American were known for their relative wealth,[102] but German women fraternized with men from all of the occupation forces.[103] Unlike most German men, Soviet and Western soldiers could provide tobacco, alcohol, food, and fuel.[104] In 1946, US Army investigators estimated at least 50% of all American troops were fraternizing with German women.[105]

The Soviets initially had no rules against their troops fraternizing with German women, but by 1947 started to isolate their troops from the German population in an attempt to stop rape and robbery by the troops.[106] Soviet authorities were also worried about the spread of venereal disease[107] and the exposure of their troops to “bourgeois ideology”.[108][109]

Fraternization fueled resentment of the male population of Occupation Zones, some of who engaged in violence against the women, largely in the form of beatings and haircuttings.[110] Members of Werwolf spread rumors of rape by black soldiers to spark resentment among the population.[111][112] African troops in the French Occupation Zone were also accused or rape and looting.[113] Interracial fraternization was condemned by both German and American authorities.[114]

German soldiers left many war children behind in nations such as France and Denmark, which were occupied for an extended period. After the war, the children and their mothers often suffered recriminations. The situation was worst in Norway, where the “Tyskerunger“ (German-kids) suffered greatly. However, today that factor is not present in Norway.[115][116]

The casualties experienced by the combatant nations impacted the demographic profile of the post war populations. One study[117] found that the male to female sex ratio in the German state of Bavaria fell as low as 60% for the most severely affected age cohort (those between 21 and 23 years old in 1946). This same study found that out-of-wedlock births spiked from approximately 10-15% during the inter-war years up to 22% at the end of the war. This increase in out-of-wedlock births was attributed to a change in the marriage market caused by the decline in the sex-ratio.

Post-war tensions

Europe

The alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union had begun to deteriorate even before World War II was over,[118] when a heated exchange of correspondence took place between Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill over whether the Polish Government in Exile, backed by Roosevelt and Churchill, or the Provisional Government, backed by Stalin, should be recognised. Stalin won.[119]

Despite its heavy losses in defeating Germany on the Eastern or Soviet-German front, the Red Army had emerged from World War II as the world's greatest land power. It was stronger in men and conventional weapons than the combined forces of the US, Great Britain, Canada and France. The Red Army had 17 divisions deployed in the Soviet zone of occupation in Berlin alone, whereas the US Army had by then been severely weakened by demobilisation and redeployment, and the British and French forces were preparing respectively to engage in policing actions and counter-insurgency operations against their former communist allies in the colonial territories of the Far East.[120]

On May 19, 1945, American Under-Secretary of State Joseph Grew declared that future war between the USSR and the US was inevitable.[121][dubious – discuss] Churchill instructed the head of the British Army, Field Marshal Alanbrooke, to investigate the possibility of fighting the USSR before British and American forces were demobilised in Europe. Alanbrooke concluded that war against the Soviet Union was not feasible.[122] Secret arrangements were concluded between American military intelligence and former key figures in the anti-communist section of German military intelligence (Abwehr), headed by General Reinhard Gehlen, to advise the Americans on how to go about establishing their own anti-Soviet networks in Europe.[123][124][125]

On March 5, 1946, in his Fulton speech, Winston Churchill said "a shadow" had fallen over Europe. He described Stalin as having dropped an "Iron Curtain" between East and West. Stalin responded by saying he believed co-existence between the Communist and the capitalist systems was impossible.[126] In mid-1948 the Soviet Union imposed a blockade on the Western zone of occupation in Berlin.

Due to the rising tension in Europe and concerns over further Soviet expansion, American planners came up with a contingency plan code-named Operation Dropshot in 1949. It considered possible nuclear and conventional war with the Soviet Union and its allies in order to counter the anticipated Soviet takeover of Western Europe, the Near East and parts of Eastern Asia due to start around 1957. In response, the US would saturate the Soviet Union with atomic and high-explosive bombs, and then invade and occupy the country.[127] In later years, to reduce military expenditures while countering Soviet conventional strength, President Eisenhower would adopt a strategy of "massive retaliation", a doctrine relying on the threat of a US nuclear strike to prevent non-nuclear incursions by the Soviet Union in Europe and elsewhere. This approach would entail a major buildup of US nuclear forces and a corresponding reduction in America's non-nuclear ground and naval strength.[128][129] The Soviet Union would view these developments as "atomic blackmail".[130]

In Greece, meanwhile, tensions had simmered between Britain and the Greek communist partisans since the winter of 1943–44, when Britain's Special Operations Executive (SOE) terminated clandestine arms supplies to the communist-led ELAS-EAM resistance movement and stepped up subsidies to the rival EDES populist movement and to the Greek pro-monarchist ruling elite, who posed no post-war threat to the capitalist system.[131][132] Civil war broke out in 1947 between Anglo-American supported royalist forces and communist-led forces, with the royalist forces emerging as the victors.[133] The US launched a massive programme of military and economic aid to Greece and to neighbouring Turkey, arising from a fear that the Soviet Union stood on the verge of breaking through the NATO defence line to the oil-rich Middle East. In what became known as the Truman Doctrine, and to gain congressional support for the aid, US president Truman on March 12, 1947 described the aid as promoting democracy in defence of the “free world”.[134]

Asia

In Asia, the surrender of Japanese forces was complicated by the split between East and West as well as by the movement toward national self-determination in European colonial territories.

Korea

At the Yalta Conference the Allies agreed that an undivided post-war Korea would be placed under four-power multinational trusteeship. After Japan's surrender, this agreement was modified to a joint Soviet-American occupation of Korea.[135] The agreement was that Korea would be divided and occupied by the Russians from the north and the Americans from the south.[136]

Korea, formerly under Japanese rule, and which had been partially occupied by the Red Army following the Soviet Union's entry into the war against Japan, was divided at the 38th parallel on the orders of the US War Department.[135][137] A United States Military Government in southern Korea was established in the capital city of Seoul.[138][139] The American military commander, Lt. Gen. John R Hodge, had enlisted many former Japanese administrative officials to serve in the new American military government.[140] North of the military line, the Russians administered the disarming and demobilisation of repatriated Korean nationalist guerrillas who had fought on the side of Chinese nationalists against the Japanese in Manchuria during World War II. Simultaneously, the Russians enabled a build-up of heavy armaments to pro-communist forces in the north.[141] The military line became a political line in 1948, when separate republics emerged on both sides of the 38th parallel, each republic claiming to be the legitimate government of Korea. It culminated in the north invading the south, and the Korean War two years later.

China

In China, the Commanding General of US Forces, General Albert C Wedemeyer, had noted in 1945 that the post-war disarming of Japanese troops by the Chinese had failed "to move smoothly" because fully armed Japanese forces were being employed to fight Mao Tse Tung and his communist guerrilla army.[142] In US president Harry Truman's words: "If we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison.” [143] The nationalist and communist Chinese forces, formerly aligned in the war against Japan, resumed their civil war, which had been temporarily suspended during the war against Japan. Communist forces were ultimately victorious and established the People's Republic of China on the mainland, while Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's nationalist forces retreated to Taiwan.

Malaya

Labour and civil unrest had broken out in the British colony of Malaya in 1946. A state of emergency was declared by the colonial authorities in 1948 when acts of terrorism started occurring. The situation deteriorated into a full-scale anti-colonial insurgency, or Anti-British National Liberation War as the insurgents referred to it, led by the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the military wing of the Malayan Communist Party.[144] The Emergency would endure for the next 12 years, ending in 1960. In 1967, communist leader Chin Peng revived hostilities, known as the Communist Insurgency War, ending in the defeat of the communists by British Commonwealth forces in 1969.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, the first war for national independence broke out on the night of December 19, 1946. Indigenous communist Viet Minh guerrillas led by Ho Chi Minh, who had resisted Japanese occupation during the war, now fought former Vichy French forces who had collaborated with the Axis and were now backed by America, France and Britain.

Covert Operations and Espionage

British covert operations in the Baltic States, which began in 1944 against the Nazis, were escalated after the war to include the recruitment and training in London of Balts, in a covert operation by the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) codenamed Jungle, for the clandestine infiltration of intelligence and resistance agents into the Baltic states between 1948 and 1955. The agents were landed on a Baltic beach by an experienced former Nazi naval captain. The states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, which had been incorporated into the Soviet Union after World War II, were singled out as primary targets. They had thriving underground dissident movements, believed by British secret services to offer the best means for destabilising the Soviet Union. This ready-made body of opposition to Stalinism was harnessed by MI6 with the co-operation of exiles living in the West. Their mission, augmented by subversive radio broadcasts from London, was to establish a pro-British insurgency network stretching from Riga to Siberia.[145] British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin hoped in particular "to detach Albania ... by promoting civil discontent, internal confusion and possible strife",[146] while Churchill considered the Balkans as a whole to be strategically important to Britain's post-war imperial interests. He saw the Balkans as a flank from which to thwart or threaten Russia.[147] The agents were mostly Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian emigrants who had been trained in the UK and Sweden and were to link up with the anti-Soviet resistance in the occupied states. Leaders of the operation included former Waffen-SS Standartenführer Alfons Rebane, Stasys Žymantas, and Rūdolfs Silarājs. The agents were transported under the cover of the "British Baltic Fishery Protection Service (BBFPS)", a cover organization launched from British-occupied Germany, using a converted former World War II E-boat captained and crewed by former members of the wartime German navy .[148] British intelligence also trained and infiltrated anti-communist agents into Russia from across the Finnish border, with orders to assassinate Soviet officials.[149] MI6's entire intelligence network in the Baltic States became completely compromised, penetrated and was covertly controlled by the KGB as a result of counter-intelligence supplied to the KGB by British spy Kim Philby.[150]

In Greece, Athens became the American Central Intelligence Agency's most important operational centre.[151] Greece's entire social, political, military and economic structure was covertly planned, decided and executed by the American Mission in Greece. Greek civil liberties were eroded, the left wing of Greek politics was all but destroyed, pro-monarchist armed forces were greatly strengthened, the trade union movement completely undermined, and a rightward swing reinforced in Greek affairs as a whole.[152] The CIA Greek station also served a springboard for all the CIA's Near East operations.[151] Communism in Greece, explained US Secretary of State Dean Acheson, had the potential to "infect Iran and all countries to the east". It also threatened to "carry infection to Africa through Asia Minor and Egypt, and to Europe through Italy and France, already threatened by the strongest domestic communist parties in Western Europe." [153] Military and economic aid approved in terms of the Truman Doctrine were chanelled to the Holy Bond of Greek Officers, or IDEA according to its Greek acronym, which was the recipient of millions of dollars in aid from Washington. Enough money, arms and supplies were provided by the Americans to equip a fighting force of at least 15,000 men, which soon emerged as the dominant force in Greek affairs. Leading IDEA members headed the armed forces while Colonel George Papadopoulos, the founder of IDEA, was promoted to head the new Greek central intelligence agency, the KYP. Led by former Nazi collaborators, it was denounced by US senator Lee Metcalf as a "a military regime of collaborators and Nazi sympathisers" serving the US as a "secret army reserve".[154]

National Security Council directive NSC-10/2 issued in June 1948 had made it permissible for American covert operations to be planned and executed in such a manner that any US government responsibility for, or involvement in, those actions would not be evident to unauthorised persons and, if uncovered, the US Government could "plausibly disclaim" any responsibility for them. The type of clandestine activities enumerated under the new directive included: "propaganda; economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance movements, guerrillas and refugee liberation groups, and support of indigenous anti-Communist elements in threatened countries of the free world." [155] The successes of clandestine American activities in Europe would later be offset by longterm damage to its reputation in Vietnam and the Middle East.[156]

The Russian intelligence service KGB believed that the Third World rather than Europe was the arena in which it could win the Cold War.[157] Moscow would in later years fuel an arms buildup in Africa and other Third World regions, notably in North Korea. Seen from Moscow, the Cold War was largely about the non-European world. The Soviet leadership envisioned a revolutionary front in Latin America. "For a quarter of a century," one expert writes, "the KGB, unlike the CIA, believed that the Third World was the arena in which it could win the Cold War." ".[158] In later years, those African countries most corrupted by the "proxy" wars of the late Cold War would become "failed states".[158]

Propaganda

As the two sides coalesced into hardened opponents, the wartime propaganda efforts that had been directed against the Axis were turned on the Third World and each other.

The British government in 1948 launched its Information Research Department (IRD), headed by a former member of Britain's wartime Political Warfare Executive (PWE), and with most of IRD's rationale and organisational structures drawn from PWE. Those of IRD's personnel not inherited from PWE were recruited from among East European emigre writers and journalists who lent their names to material supplied by the British secret service. Individual correspondents party to this arrangement also included writers and reporters on all the major British national newspapers, with which IRD made arrangements for the newspapers to select, reprint and distribute anti-Soviet articles provided by IRD for syndication and re-publication abroad. It was a condition of this agreement that the articles could not be altered in any way, nor could the covert source be revealed. At the same time, MI5 and MI6 agents were placed on newspaper editorial staffs.[159] Red Army soldiers serving in Germany also became targets for IRD propaganda, because they comprised "a special category of listeners to the BBC's Russian service." It was to these BBC broadcasts in particular that IRD attached great importance, with the intention of encouraging disaffected Red Army personnel to defect. This, according to a top secret document of the time, was because "in the present state" of British intelligence about Russia, it was "vital for (Britain) to encourage defection, without which it is almost impossible to obtain the inside information which we so urgently need." In the event, however, only a handful of Russian soldiers defected — and then only in consequence of their relationships with German women.[160][161]

Under cover of the National Committee for a Free Europe (NCFE), the American CIA established two radio broadcasting projects, Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL), with headquarters in New York and radio transmitters in West Germany. NCFE was officially registered as a charitable, tax-free non-government organisation funded by private donation. Under the direction of CIA deputy director Allen Dulles, NCFE was engaged specifically in co-ordinating propaganda operations aimed at provoking a climate of dissent as the planned precursor to a general armed uprising behind Soviet lines.[162] RFE began broadcasting to central and eastern Europe in 1950,[163][164] staffed mainly by East European exiles including former Nazi collaborators and war criminals who had entered the US after World War II under the Displaced Persons Act and the Refugee Relief Act. Among them were propagandists who had worked for Hitler.[165]

The CIA also established a secret broadcasting station on Taiwan, which posed as a clandestine broadcasting station within mainland communist China. To achieve credibility in its propaganda beamed to the mainland, the bogus radio station combined disinformation with accurate information gleaned from genuine domestic Chinese broadcasts, while pretending the broadcasts were under internal dissident control. So convincing were the bogus transmissions that in the late 1940s and early 1950s some of the CIA's own media analysts and many Western academic researchers were deceived into believing the broadcasts were genuine.[166]

Recruitment of former enemy scientists

When the divisions of postwar Europe began to emerge, the war crimes programmes and denazification policies of Britain and the United States were relaxed in favour of recruiting German scientists, especially nuclear and long-range rocket scientists.[167] Many of these, prior to their capture, had worked on developing the German V-2 long-range rocket at the Baltic coast German Army Research Center Peenemünde.

Western Allied occupation force officers in Germany were ordered to refuse to cooperate with the Russians in sharing captured wartime secret weapons.[168]

In Operation Paperclip, beginning in 1945, the United States imported 1,600 German scientists and technicians, as part of the intellectual reparations owed to the US and the UK, including about $10 billion in patents and industrial processes.[169] The $10 billion compares to the 1948 US GDP $258 billion, and to the total Marshall plan (1948–52) expenditure of $13 billion, of which Germany received $1.4 billion (partly as loans). In late 1945, three German rocket-scientist groups arrived in the US for duty at Fort Bliss, Texas, and at White Sands Proving Grounds, New Mexico, as “War Department Special Employees”.[170] In early 1950, legal US residency for some of the Project Paperclip specialists was effected through the US consulate in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico; thus, Nazi scientists legally entered the US from Latin America. Eighty-six aeronautical engineers were transferred to Wright Field, where the US had Luftwaffe aircraft and equipment captured under Operation Lusty. The United States Army Signal Corps employed 24 specialists — including the physicists Georg Goubau, Gunter Guttwein, Georg Hass, Horst Kedesdy, and Kurt Lehovec; the physical chemists Rudolf Brill, Ernst Baars, and Eberhard Both; the geophysicist Dr. Helmut Weickmann; the optician Gerhard Schwesinger; and the engineers Eduard Gerber, Richard Guenther, and Hans Ziegler.[171] By 1959, a further ninety-four Operation Paperclip men had gone to the US, including Friedwardt Winterberg and Friedrich Wigand.

The wartime activities of some Operation Paperclip scientists would later be investigated. The aeromedical library at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas had been named after Hubertus Strughold in 1977. However, it was later renamed because documents from the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal linked Strughold to medical experiments in which inmates from Dachau were tortured and killed.[172] Arthur Rudolph was deported in 1984, though he was not prosecuted, and West Germany granted him citizenship.[173] Similarly, Georg Rickhey, who came to the United States under Operation Paperclip in 1946, was returned to Germany to stand trial at the Mittelbau-Dora war crimes trial in 1947, was acquitted, and returned to the United States in 1948, eventually becoming a US citizen.[174]

The Russians began Operation Osoaviakhim in 1946. NKVD and Soviet army units effectively deported thousands of military-related technical specialists from the Soviet occupation zone of post-World-War-II Germany to the Soviet Union.[175] Much related equipment was also moved, the aim being to virtually transplant research and production centres, such as the relocated V-2 rocket centre at Mittelwerk Nordhausen, from Germany to the Soviet Union. Among the people moved were Helmut Gröttrup and about two hundred scientists and technicians from Mittelwerk.[176] Personnel were also taken from AEG, BMW's Stassfurt jet propulsion group, IG Farben's Leuna chemical works, Junkers, Schott AG, Siebel, Telefunken, and Carl Zeiss AG.[176]

The operation was commanded by NKVD deputy Colonel General Serov,[177] outside the control of the local Soviet Military Administration[178] The major reason for the operation was the Soviet fear of being condemned for noncompliance with Allied Control Council agreements on the liquidation of German military installations.[179]

Some Western observers thought Operation Osoaviakhim was a retaliation for the failure of the Socialist Unity Party in elections, though Osoaviakhim was clearly planned before that.[176] 92 trains were used to transport the specialists and their families (an estimated 10,000-15,000 people).[176]

Founding of the United Nations

As a general consequence and in an effort to maintain international peace,[180] the Allies formed the United Nations, which officially came into existence on October 24, 1945,[181] and adopted The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, "as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations." The USSR abstained from voting. The US did not ratify the social and economic rights sections.[182]

See also

- Operation Jungle

- Operation Unthinkable

- Operation Paperclip

- Atlantic Charter

- Danube River Conference of 1948

- Japanese holdouts

- Post-World War II economic expansion

- Black Tulip — the eviction of Germans from the Netherlands after the war

- Consequences of German Nazism

- The rehabilitation of Germany after World War II

- Japanese post-war economic miracle

- Bretton Woods Agreement

Notes

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (November 2010) |

- ^ Senn, Alfred Erich, Lithuania 1940 : revolution from above, Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 ISBN 9789042022256

- ^ Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0300112041.

- ^ Wettig, Gerhard (2008). Stalin and the Cold War in Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0742555429.

- ^ Granville, Johanna, The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956, Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58544-298-4

- ^ Grenville, John Ashley Soames (2005). A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century. Routledge. pp. 370–371. ISBN 0415289548.

- ^ Crampton 1997, pp. 216–7[full citation needed]

- ^ Eastern bloc, The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.

- ^ Cook 2001, p. 17

- ^ Wettig 2008, pp. 96–100 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWettig2008 (help)

- ^ “Japan and North America: First contacts to the Pacific War”, Ellis S. Krauss, Benjamin Nyblade, 2004, pg. 351 [1]

- ^ a b "Yomiuri Shimbun".

- ^ "Montreal Gazette".

- ^ "Japan Times".

- ^ Michael Ellman and S. Maksudov, "Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: A Note", Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 671-680

- ^ Ibid.,

- ^ "20m Soviet war dead may be underestimate”, Guardian, 30 April 1994 quoting Professor John Erickson of Edinburgh University, Defence Studies.

- ^ Edwin Bacon, "Glasnost and the Gulag: New Information on Soviet Forced Labour around World War II", Soviet Studies, Vol. 44, No. 6 (1992), pp. 1069-1086.

- ^ Michael Ellman, "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments”, Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 54, No. 7 (Nov., 2002), pp. 1151-1172

- ^ Glenn E. Curtis, ed. Russia: A Country Study, Washington: Library of Congress, 1996

- ^ Charles F Pennacchio, East German communists and the origins of the Berlin blockade

- ^ Ibid.,

- ^ This account of the blocade draws on Douglas Botting, From the Ruins of the Reich: Germany 1945-1949, New York: Random House; 1985, pp. 66, 113 241 291. ISBN 0517558653

- ^ Cost of Defeat Time Magazine Monday, April 8, 1946

- ^ Norman M. Naimark The Russians in Germany pg. 206

- ^ Frederick H. Gareau "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany" The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Jun., 1961), pp. 517-534

- ^ Ray Salvatore Jennings "The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49 pg.15

- ^ Ray Salvatore Jennings “The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49 pg.15

- ^ Pas de Pagaille! Time Magazine 28 July 1947.

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.2 [2]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.41 [3]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.2 [4]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.35 [5]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.70 [6]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.70 [7]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.70 [8]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.70 [9]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.71 [10]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.71 [11]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.71 [12]

- ^ The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-1968 Hanna Schissler, Princeton University Press, 2001, p.27 [13]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.71 [14]

- ^ The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-1968 Hanna Schissler, Princeton University Press, 2001, p.93 [15]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.41 [16]

- ^ ”Werwolf!: the history of the National Socialist guerrilla movement, 1944-1946”, Perry Biddiscombe, University of Toronto Press, 1998, p.260 [17]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.72 [18]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.72 [19]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.78 [20]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.77 [21]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.32 [22]

- ^ ”Werwolf!: the history of the National Socialist guerrilla movement, 1944-1946”, Perry Biddiscombe, University of Toronto Press, 1998, p.260 [23]

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/berlin_01.shtml

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.72 [24]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.72 [25]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.72 [26]

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.81 [27]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.107 [28]

- ^ The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-1968 Hanna Schissler, Princeton University Press, 2001, p.28 [29]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.36 [30]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.35 [31]

- ^ ”Berlin: the downfall, 1945”, Antony Beevor, Viking, 2002, p.410 [32]

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.81 [33]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.35 [34]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.35 [35]

- ^ ”Berlin: the downfall, 1945”, Antony Beevor, Viking, 2002, p.410 [36]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.34 [37]

- ^ ”Berlin: the downfall, 1945”, Antony Beevor, Viking, 2002, p.410 [38]

- ^ ”Berlin: the downfall, 1945”, Antony Beevor, Viking, 2002, p.410 [39]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.35 [40]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.79 [41]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.81 [42]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.42 [43]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.81 [44]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.43 [45]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.83 [46]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.79 [47]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.79 [48]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.79 [49]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.79 [50]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.84 [51]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.97 [52]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.98 [53]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.44 [54]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.79 [55]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.84 [56]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.84 [57]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.88 [58]

- ^ ”Berlin: the downfall, 1945”, Antony Beevor, Viking, 2002, p.29 [59]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.102 [60]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.104 [61]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.108 [62]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.88 [63]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.79 [64]

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.106 [65]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.34 [66]

- ^ Norman M. Naimark. The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949. Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-674-78405-7 pp. 106.

- ^ Dear editor: letters to Time magazine, 1923-1984 “,Phil Pearman, Salem House, 1985, p.75 [67]

- ^ Politicization of sexual violence: from abolitionism to peacekeeping”, Carol Harrington, Ashgate Pub., 2010, p.80 [68]

- ^ The Interpreter”, Alice Kaplan, Simon and Schuster, 2005, p.218 [69]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.107 [70]

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.96 [71]

- ^ West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.34 [72]

- ^ Perry Biddiscombe. Dangerous Liaisons: The Anti-Fraternization Movement in the U.S. Occupation Zones of Germany and Austria, 1945-1948. Journal of Social History, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Spring, 2001), pp. 611-647. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3789820

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.96 [73]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.93 [74]

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.98 [75]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.92 [76]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.93 [77]

- ^ ” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.95 [78]

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.96 [79]

- ^ Perry Biddiscombe. Dangerous Liaisons: The Anti-Fraternization Movement in the U.S. Occupation Zones of Germany and Austria, 1945-1948. Journal of Social History, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Spring, 2001), pp. 611-647. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3789820

- ^ ”Werwolf!: the history of the National Socialist guerrilla movement, 1944-1946”, Perry Biddiscombe, University of Toronto Press, 1998, p.51 [80]

- ^ ”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.99 [81]

- ^ ”Werwolf!: the history of the National Socialist guerrilla movement, 1944-1946”, Perry Biddiscombe, University of Toronto Press, 1998, p.260 [82]

- ^ The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-1968 Hanna Schissler, Princeton University Press, 2001, p.167 [83]

- ^ STUART, JULIA (February 2, 2003). "SLEEPING WITH THE ENEMY; SPAT AT, ABUSED, SHUNNED BY NEIGHBOURS. THEIR CRIME?". History News Network. Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ "Norway's "lebensborn"". BBC News. 5 December 2001. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Michael Kvasnicka and Dirk Bethmann "WORLD WAR II, MISSING MEN, AND OUT-OF-WEDLOCK CHILDBEARING 1-Oct-2007, THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, KOREA UNIVERSITY, Discussion Paper No. 07-30

- ^ Kantowicz, Edward R (2000). Coming Apart, Coming Together. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 0802844561.

- ^ Stewart Richardson, Secret History of World War II, New York: Richardson & Steirman, 1986, p.vi. ISBN 0931933056

- ^ Y Larionov, N Yeronin, B Solovyov, V. Timokhovich, World War II Decisive Battles of the Soviet Army, Moscow: Progress 1984, p.452

- ^ Yefim Chernyak, Ambient Conflicts: History of Relations between Countries with Different Social Systems, Moscow: Progress Publisers, 1987, p. 360

- ^ David Fraser, Alanbrooke, London: Collins, 1982, p. 489.

- ^ Christopher Simpson, Blowback: America's Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1988, pp. 42, 44 ISBN 1555841066

- ^ Richard Harris Smith, OSS: Secret history of the CIA, Berkeley: University of California Press 1972, p. 240 ISBN 0440567351

- ^ * Höhne, Heinz; Zolling, Hermann (1972). The General was a Spy, The Truth about General Gehlen-20th Century Superspy. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc.

- ^ Anthony Cave Brown, Dropshot: The United States Plan for War with the Soviet Union in 1957, New York: Dial Press, 1978, p.3

- ^ Cave Brown, op cit, p. 169

- ^ John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Continment, New York: Oxford University Press, pp.127-9

- ^ Walter LaFeber, America, Russia and the Cold War 1945-1966, New York: John Wiley, 1968, pp.123-200

- ^ Chernyak, op cit, p.359

- ^ LS Stavrianos, "The Greek National Liberation Front (EAM): A Study in Resistance, Organisation and Administration", Journal of Modern History, March 1952, pp.42-55.

- ^ Prokopis Papastratis, "The British and the Greek Resistance Movements EAM and EDES", in Marion Sarafis (ed.), Greece: From Resistance to Civil War, Nottingham: Spokesman 1980, p. 36

- ^ Christopher M Woodhouse, The Struggle for Greece 1941-1949, London: Hart-Davis 1976, pp.3-34, 76-7

- ^ Lawrence S Wittner, “How Presidents Use the Term ‘Democracy’ as a Marketing Tool”, Retrieved October 29, 2010

- ^ a b Dennis Wainstock, Truman, McArthur and the Korean War, Greenwood, 1999, p.3

- ^ Dennis Wainstock, Truman, McArthur and the Korean War, Greenwood, 1999, pp.3, 5

- ^ Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, Korea: The unknown war, London: Viking, 1988, pp. 10, 16, ISBN 0670819034

- ^ Edward Grant Meade, American military government in Korea,: King's Crown Press 1951, p.78

- ^ A. Wigfall Green, The Epic of Korea, Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1950, p.54

- ^ Walter G Hermes , Truce Tent and Fighting Front, Washington DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1992, p.6

- ^ James M Minnich, The North Korean People's Army: origins and current tactics, Naval Institute Press, 2005 pp.4-10

- ^ Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, (9 vols) Tokyo and New York: Dondasha 1983, Vol VII, p.202.

- ^ Harry S Truman, Memoirs, (2 vols), New York: Doubleday 1956, Vol II, p.66.

- ^ Mohamed Amin and Malcolm Caldwell (eds.), The Making of a Neo Colony, London: Spokesman Books, 1977, footnote, p. 216

- ^ Anthony Cavendish, Inside Intelligence, London: Palu 1987, p.55.

- ^ Ray Merrick, "The Russian Committee of the British Foreign Office and the Cold War, 1946-1947", Journal of Contemporary History, Vol 20, 1985, pp.453-468

- ^ Anthony Verrier, Through the Looking Glass: British Foreign Policy in the Age of Illusions, London: Jonathan Cape, 1983, pp.34-6

- ^ Sigured Hess, "The British Baltic Fishery Protection Service (BBFPS) and the Clandestine Operations of Hans Helmut Klose 1949-1956." Journal of Intelligence History vol. 1, no. 2 (Winter 2001)

- ^ Tom Bower, The Red Web: MI6 and the KGB, London: Aurum, 1989, pp. 19, 22-3 ISBN 1 85410 080 7

- ^ Bower, op cit, pp. 38, 49, 79

- ^ a b Yiannis Roubatis and Karen Wynn, "CIA Operations in Greece", in Philip Agee and Louis Wolf (eds), Dirty Work: The CIA in Western Europe, London: Zed, 1981, pp. 147-157

- ^ Lawrence S Wittner, American Intervention in Greece 1943-1949, New York: Columbia, 1982, p. 7

- ^ Bruce R Kuniholm, Origins of the Cold War in the Near East, Princeton: Princeton University Press 1980, p.411

- ^ The Times, 17 November 1971.

- ^ William M Leary (ed,) The Central Intelligence Agency: History and Documents, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1984, pp.131-33

- ^ Tony Judt, "A Story Still to Be Told", New York Review of Books, Vol 53, March 23, 2006]

- ^ Christopher Andrew & Vasili Mitrokhin, The World was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World, New York: Basic Books, 2005, foreword, p. xxvi

- ^ a b Judt, "A Story Still to Be Told"

- ^ Lyn Smith, "Covert British Propaganda: The Information Research Department, 1947-1977", Millennium, Vol IX 1980, p. 72 et seq.,

- ^ Wesley K Wark, "Coming in from the Cold: British Propaganda and Red Army Defectors", 1945-1952, International History Review, Vol IX No. 1, February 1987, pp. 54-71, and cf., Appendix II listing numbers and reasons for defection.

- ^ Verrier, op cit, p.52

- ^ Stewart Steven, Operation Splinter Factor, London: Hodder and Stoughton 1974, pp. 98-101, 126, 131

- ^ Robert T Holt, Radio Free Europe, Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis 1958, p.12

- ^ David Wise and Thomas Ross, The Invisible Government, New York: Vintage 1964, p. 326ff

- ^ Simpson, op cit, pp. 89, 108, 124-36, 177, 184, 201, 205, 219, 224, 247-8, 267, 269 -- citing classified information made available under the US Freedom of Information Act.

- ^ Victor Marchetti and John D Marks, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, London: Jonathan Cape, 1974. pp. 158-60

- ^ Tom Bower, The Paperclip Conspiracy: Battle for the spoils and secrets of Nazi Germany, London: Michael Joseph, 1987, pp.75-8, ISBN 0718127447

- ^ Bower, op cit, pp.95-6

- ^ Naimark, Science Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany p.60

- ^ Huzel, Dieter K (1960). Peenemünde to Canaveral. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 27, 226.

- ^ Operation Paperclip and Camp Evans

- ^ Walker, Andres (2005-11-21). "Project Paperclip: Dark side of the Moon". BBC news. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ^ Hunt, Linda (May 23, 1987). "NASA's Nazis". Nation.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|work=and|magazine=specified (help) - ^ Michael J. Neufeld (2008). Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War Vintage Series. Random House, Inc. ISBN 9780307389374.

- ^ Norman Naimark (1995). The Russians in Germany. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674784055.

{{cite book}}: Text "p.220" ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Norman Naimark (1995). The Russians in Germany. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674784055.

{{cite book}}: Text "p.221" ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "Norman Naimark 1995" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Norman Naimark (1995). The Russians in Germany. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674784055.

{{cite book}}: Text "p.220" ignored (help) - ^ Norman Naimark (1995). The Russians in Germany. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674784055.

{{cite book}}: Text "p.223" ignored (help) - ^ Norman Naimark (1995). The Russians in Germany. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674784055.

{{cite book}}: Text "p.225" ignored (help) - ^ Yoder, Amos. The Evolution of the United Nations System, p. 39.

- ^ History of the UN

- ^ "Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Questions and Answers" (PDF). Amnesty International. p. 6. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

Further reading

- Blum, William (1986). The CIA: A Forgotten History. London: Zed.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cook, Bernard A (2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0815340575.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Granville, Johanna (2004). The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1585442984.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grenville, John Ashley Soames (2005). A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century. Routledge. ISBN 0415289548.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Iatrides (ed), John O (1981). Greece in the 1940s: A Nation in Crisis. Hanover and London: University Press of New England.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Howard (1989). A New Kind of War: America's global strategy and the Truman Doctrine in Greece. London: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laar, Mart, Tiina Ets, Tonu Parming (1992). War in the Woods: Estonia's Struggle for Survival, 1944-1956. Howells House. ISBN 0929590082.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Männik, Mart (2008). A Tangled Web: British Spy in Estonia. Tallinn: Grenader Publishing. ISBN 9789949448180.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martin, David (1990). The Web of Disinformation: Churchill's Yugoslav Blunder. San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-180704-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Naimark, Norman M. (1995). The Russians in Germany; A History of the Soviet Zone of occupation, 1945-1949. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-78406-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peebles, Curtis (2005). Twilight Warriors. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1591146607.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300112041.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sayer, Ian & Douglas Botting (1989). America's Secret Army: The Story of Counter-intelligence Corps. London: Grafton.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stevenson, William (1973). The Bormann Brotherhood. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wettig, Gerhard (2008). Stalin and the Cold War in Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0742555429.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wiesenthal, Simon (1984). SS Colonel Walter Rauff: The Church Connection 1943-1947. Los Angeles: Simon Wiesenthal Center.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)