HIV/AIDS in the United States

This article needs to be updated. (January 2009) |

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (March 2010) |

The history of HIV/AIDS in the United States began in about 1969, when HIV likely entered the United States through a single infected immigrant from Haiti.[2] In the early 1980s, doctors in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco began seeing young men with Kaposi's Sarcoma, a cancer usually associated with elderly men of Mediterranean ethnicity.

As the knowledge that men who had sex with men were dying of an otherwise rare cancer began to spread throughout the medical communities, the syndrome began to be called by the colloquialism "gay cancer." As medical scientists discovered that the syndrome included other manifestations, such as pneumocystis pneumonia, (PCP), a rare form of fungal pneumonia, its name was changed to "GRID," or Gay Related Immune Deficiency.[3] This had an effect of boosting homophobia and adding stigma to homosexuality in the general public, particularly since it seemed that unprotected anal sex was the prevalent way of spreading the disease.

Within the medical community, it quickly became apparent that the disease was not specific to men who have sex with men (as blood transfusion patients, intravenous drug users, heterosexual and bisexual women, and newborn babies became added to the list of afflicted), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) renamed the syndrome AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) in 1982.

Hemophiliacs, who require injections of blood clotting factor as a course of treatment, during the late 1970s and 1980s also contracted HIV in large numbers worldwide through the spread of contaminated blood products. It is estimated that nearly 1 million individuals are currently infected with HIV in the country, and the number appears to be increasing each year.

In the United States, about one third of HIV/AIDS cases newly diagnosed in 2007 resulted from heterosexual encounters, the most rapidly growing transmission category. Male to male sexual contact accounted for about half of new cases, and intravenous drug use contributed about a fifth of cases.[4] Despite the availability of syringe access programs, many individuals continue to share and use dirty or infected needles in most American cities.[5]

Public perception

Regarding the social effects of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, there has been since the 1980s a "profound re-medicalization of sexuality".[6][7][verification needed]

One of the best-known works on the history of HIV is 1987's book And the Band Played On, by Randy Shilts. Shilts contends that Ronald Reagan's administration dragged its feet in dealing with the crisis due to homophobia , while the gay community viewed early reports and public health measures with corresponding distrust, thus allowing the disease to spread and hundreds of thousands of people to needlessly die. This resulted in the formation of ACT-UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power by Larry Kramer.

This work popularized the misconception that the disease was introduced by a gay flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas, referred to as "Patient Zero". However, subsequent research has revealed that there were cases of AIDS much earlier than initially known. HIV-infected blood samples have been found from as early as 1959 in Africa (see HIV main entry), and HIV has been shown to have caused the death of a sexually active St. Louis adolescent male in 1969.[8]

Shilts also details the fact that despite recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control, the Red Cross and other non-profit blood banking organizations refused to ban bisexual and gay men from donating blood in an effort to keep the blood bank industry from suffering shortages, particularly in cities having large homosexual communities; the same cities where AIDS was first discovered in. As a result, tens of thousands of hemophiliacs and transfusion recipients were infected and died.

It has been theorized that a series of inoculations against hepatitis that were performed in the gay community of San Francisco were tainted with HIV. Although there was a high correlation between recipients of that vaccination and initial cases of AIDS, this theory has never been proven. HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C are bloodborne diseases with very similar modes of transmission, and those at risk for one are at risk for the others.[9]

Activists and critics of current AIDS policies allege that another preventable impediment to the attack on the disease was the academic elitism of "celebrity" scientists. Robert Gallo, an American scientist who was one of many to attempt to figure out if there was some kind of new virus in the people who were affected by the disease, became embroiled in a legal battle with French scientist Luc Montagnier. Gallo, too, appeared hung up on the possible connection between the virus causing AIDS and HTLV, a retrovirus that he had worked with previously. Critics claim that because some scientists (and biological research companies) wanted glory and fame (and lucrative patent rights), research progress was delayed and more people needlessly died. Eventually, after meeting, the French scientists and Gallo agreed to "share" the discovery of HIV.

Publicity campaigns were started in attempts to counter the often vitriolic and homophobic perception of AIDS as a "gay plague." In particular this included the Ryan White case, red ribbon campaigns, celebrity dinners, the 1993 film version of And the Band Played On, sex education programs in schools, and television advertisements. Announcements by various celebrities that they had contracted HIV (including actor Rock Hudson, basketball star Magic Johnson, tennis player Arthur Ashe and singer Freddie Mercury) were significant in making the general public aware of the dangers of the disease to people of all sexual orientations.

Containment

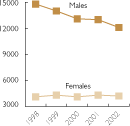

Great progress was made in the U.S. following the introduction of three-drug anti-HIV treatments ("cocktails") that included protease inhibitors. David Ho, a pioneer of this approach, was honored as Time Magazine Man of the Year for 1996. Deaths were rapidly reduced by more than half, with a small but welcome reduction in the yearly rate of new HIV infections. Since this time, AIDS deaths have continued to decline, but much more slowly, and not as completely in black Americans as in other population segments.[10][11] The situation remains fragile – for example, Britain recently suffered a resurgence in HIV infections despite similar measures.[citation needed]

Travel restrictions

The second prong of the American approach to containment has been to maintain strict entry controls to the country for people with HIV or AIDS. Under legislation enacted by the United States Congress in 1993, patients found importing anti-HIV medication into the country were arrested and placed on flights back to their country of origin.

Some HIV-positive travellers took to sending anti-HIV medication through the post to friends or contacts in advocacy groups in advance. This meant that the traveller would not be discovered with any medication. However, the security clampdown following the September 11 attacks in 2001 meant this was no longer an option.

The only legal alternative to this was to apply for a special visa beforehand, which entailed interview at an American Embassy, confiscation of the passport during the lengthy application process, and then, if permission were granted, a permanent attachment being made to the applicant's passport.

This process was condemned as intrusive and invasive by a number of advocacy groups, on the grounds that any time the passport was later used for travel elsewhere or for identification purposes, the holder's HIV status would become known. It was also felt that this rule was unfair because it applied even if the traveller was covered for HIV-related conditions under their own travel insurance.

In early December 2006, President George W. Bush indicated that he would issue an executive order allowing HIV-positive people to enter the United States on standard visas. It is unclear whether applicants will still have to declare their HIV status.[12] However, as of February 2008, the ban was still in effect.[needs update] In August 2007, Congressperson Barbara Lee of California introduced House Resolution 3337, the HIV Nondiscrimination in Travel and Immigration Act of 2007. This bill would allow travelers and immigrants entry to the United States without having to disclose their HIV status. As of February 2008 it is still pending.[13][dead link]

In July 2008, then President George W. Bush signed the bill that would effectively lift the ban in statutory law. As of September 2009, the Department of Health and Human Safety still holds the ban in administrative (written regulation) law. They have said they are working towards removing this from the written regulations, but as with most laws, it needs to be drafted and then go to public commentary before it can be passed. As of now, HIV positive foreigners wishing to enter the US need to apply for a special Visa. This process (which use to take approximately 18 days) now has a expedited process in which the applicant can be granted the waiver on the same day as their interview. This Visa which follows a protocol referred to as a "Final Rule" has many stipulations, some of which include the need to have adequate medication for your trip (if applicable), adequate medical insurance as well as your trip having a 30 day limit, with no possibility of extension. While people still believe that this will identify these people as HIV positive when they travel, the US government has assured the public that the visa does not outright state anything regarding HIV status. While it is viewed by many as a step in the right direction, some activists still believe that it is far behind schedule.

On October 30, 2009 President Barack Obama reauthorized the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Bill which expanded care and treatment through federal funding to nearly half a million.[14] He also announced that the Department of Health and Human Services crafted regulation that would end the HIV Travel and Immigration Ban effective in January 2010;[14] on January 4th, 2010, the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention removed HIV status as a factor to be considered in the granting of travel visas.[15]

Medicine disbursement

Previously in the U.S., HIV drugs were only given to those who had T-cell counts of under 200, but that had been boosted in the mid 2000's to 350 on advice from the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) guidelines which recommend therapy for all patients at 350 or certain patients higher. For the uninsured, there are generally two funding sources, Medicaid and AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAP), both administered differently in each state but still consistent with federal requirements established by the Ryan White Care Act.

According to a recent large scale study, asymptomatic HIV positive patients who started on medication with T-cell counts 350 to 500 had a 70 percent higher survival rate than those who waited. The results from this shows that waiting even until the cell count reaches 350 (current JAMA recommendation) increases the risk of death, let alone the Medicaid eligible 200.[16] As many patients can't afford medicines without Medicaid help, HIV annual death counts have failed to decline significantly since 2002 despite great advances made before that date. The number of new cases in children has dropped significantly as a result of better screening of infected mothers as well as having established uniform testing and screening of blood products. This is not the same for places outside the United States, especially developing countries where the number of children affected by HIV continue to rise exponentially each year. [17]

Mortality and morbidity

Invariably, HIV is a silent disease when first acquired, and this period of latency varies. Current estimates indicate that close to half a million individuals have died of AIDS in the USA. The progression from HIV to AIDS varies from 5–12 years. In the past, most individuals succumbed to the disease in 1–2 years. However, since the introduction of potent anti retroviral drug therapy and better prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, death rates have significantly declined. [18]

Current status

The CDC estimates the cumulative number of deaths of persons with AIDS in the U.S. through 2007 to be 583,298, including 4,891 children under the age of 13. Cumulative estimated AIDS cases are 1,051,875.[20] Persons living with HIV in reporting cities with confidential name based reporting (a fraction of the USA only) was 1,106,400 in 2006.[21] UNAIDS estimates that there are a total of about 1,200,000 people in the U.S. living with HIV as of 2005.[22]

In California alone, 184,429 cumulative people (including children) have reported to contract the HIV virus by December 2008. Of those, 85,958 have died, with 31,076 in Los Angeles County, 18,838 in San Francisco, and 7,135 in San Diego County.[23]

In 2007, 119,929 People were living with HIV in New York State, with 92,669 in New York City alone.[24][needs update]

AIDS continues to be a problem with illegal sex workers and injecting drug users. The main route of transmission for women is through heterosexual sex, and the main risk factor for them is non-protection and the undisclosed risky behaviour of their sexual partners. Experts attribute this to "AIDS fatigue" among younger people who have no memory of the worst phase of the epidemic in the 1980s and early 1990s, as well as "condom fatigue" among those who have grown tired of and disillusioned with the unrelenting safer sex message. This trend is of major concern to public health workers.

AIDS is one of the top three causes of death for African American men aged 25–54 and for African American women aged 35–44 years in the United States of America. In the United States, African Americans make up about 47% of the total HIV-positive population and more than half of new HIV cases, despite making up only 12% of the population. African American women are 19 times more likely to have HIV than white women.

In a 2008 study, the Center for Disease Control found that, of the study participants who were men who had sex with men ("MSM"), almost one in five (19%) had HIV and "among those who were infected, nearly half (44 percent) were unaware of their HIV status." The research found that those who are white MSM "represent a greater number of new HIV infections than any other population, followed closely by black MSM — who are one of the most disproportionately affected subgroups in the U.S" and that most new infections among white MSM occurred among those aged 30-39 followed closely by those aged 40-49, while most new infections among black MSM have occurred among young black MSM (aged 13-29).[25][26]

See also

- Adult Industry Medical Health Care Foundation

- AIDS Education and Training Centers (AETCs)

- AIDS pandemic

- People With AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement

References

- ^ "Estimated Number of New HIV Cases—22 States 2006, CDC" (PDF). US Centers for Disease Control. April 3, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ Gilbert MT, Rambaut A, Wlasiuk G, Spira TJ, Pitchenik AE, Worobey M (2007). "The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the Americas and beyond". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (47): 18566–70. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705329104. PMC 2141817. PMID 17978186. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Altman, Charles (June 18, 1982). "Clue Found on Homosexuals' Precancer Syndrome". New York Times. New York Times Company. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/us.htm

- ^ Davis CS, Beletsky L (2009). "Bundling occupational safety with harm reduction information as a feasible method for improving police receptiveness to syringe access programs: evidence from three U.S. cities". Harm Reduct J. 6: 16. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-16. PMC 2716314. PMID 19602236. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Aggleton, Peter; Parker, Richard Bordeaux; Barbosa, Regina Maria (2000). Framing the sexual subject: the politics of gender, sexuality, and power. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-520-21838-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vance, Carole S. (1991). "Anthropology rediscovers sexuality: a theoretical comment". Soc Sci Med. 33 (8): 875–84. PMID 1745914.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Highleyman L (1999). "First AIDS case in 1969". BETA. 12 (4): 5. PMID 11367253.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Bloodborne Infectious Diseases HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus". US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. March 10, 2010. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Phill; Wright, Kai; Isbell, Michael T. (2008). "Left Behind: Black America: a Neglected Priority in the Global AIDS Epidemic" (PDF). Black AIDS Institute. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ "Deaths in New York City Reached Historic Low in 2002" (Press release). New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. January 30, 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Russell, Sabin (December 2, 2006). "Bush to ease rule limiting HIV-positive foreign visitors". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "House Resolution 3337". GovTrack.us. Civic Impulse LLC. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Crowley, Jeffrey (October 30, 2009). "Honoring the Legacy of Ryan White". WhiteHouse.gov. Office of the President of the United States. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "HIV Final Rule". United States Department of State. 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ Smith, Michael (October 27, 2008). "ICAAC-IDSA: HIV Treatment Started Sooner than Later Lessens Early Death Risk". MedPage Today, LLC. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "Epidemiology Research, HIV/AIDS". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. November 12, 2009. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ "2008 HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Annual Report" (PDF). San Francisco Department of Public Health. July 9, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "HIV/AIDS Basic Statistics". US Centers for Disease Control. February 26, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "Basic Statistics HIV/AIDS". US Centers for Disease Control. February 26, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "HIV Prevalence Estimates – United States, 2006". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 57, no. 39. US Centers for Disease Control. October 3, 2008. pp. 1073–1076.

- ^ "North America, Western and Central Europe" (PDF). AIDS epidemic update Regional Summary. UNAIDS. April 15, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ "December 2008 Monthly HIV/AIDS Statistics" (PDF). California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS. July 9, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "New York State HIV/AIDS Surveillance Annual Report For Cases Diagnosed Through December 2007" (PDF). New York State Department of Public Health. 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/.../docs/FastFacts-MSM-FINAL508COMP.pdf CDC Fact Sheet - HIV and AIDS among Gay and Bisexual Men - Sept 2010]

- ^ CDC: One In Five Gay Men HIV-Positive

Bibliography

- Cante, Richard C. (2008). Gay Men and the Forms of Contemporary US Culture. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0 7546 7230 1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Bogart, Laura; Thorburn, Sheryl (2005). "Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans?". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 38 (2): 213–8. PMID 15671808.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Walker, Robert Searles (1994). AIDS: Today, Tomorrow : an Introduction to the HIV Epidemic in America (2nd ed.). Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press Intl. ISBN 0391038591. OCLC 30399464.

- Siplon, Patricia (2002). AIDS and the policy struggle in the United States. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0878403783. OCLC 48964730.

External links