Garden city movement

The garden city philosophy is a method of urban planning that was initiated during 1898 by Sir Ebenezer Howard in the United Kingdom. Garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained, communities surrounded by "greenbelts" (parks), containing proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture.

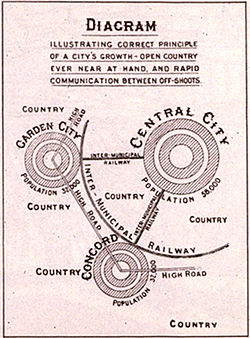

Inspired by the Utopian novel Looking Backward, Howard published his book To-morrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform during 1898 (which was reissued during 1902 as Garden Cities of To-morrow). His idealised garden city would house 32,000 people on a site of 6000 acres (2400 ha), planned on a concentric pattern with open spaces, public parks and six radial boulevards, 120 ft (37 m) wide, extending from the centre. The garden city would be self-sufficient and when it had full population, another garden city would be developed nearby. Howard envisaged a cluster of several garden cities as satellites of a central city of 50,000 people, linked by road and rail.[1]

Early development

Howard’s To-morrow: a peaceful path to real reform sold enough copies to result in a second edition, Garden Cities of To-morrow. This success provided him the support necessary to pursue the chance to bring his vision into reality. Howard believed that all people agreed the overcrowding and deterioration of cities was one of the troubling issues of their time. He quotes a number of respected thinkers and their disdain of cities. Howard’s garden city concept combined the town and country in order to provide the working class an alternative to working on farms or ‘crowded, unhealthy cities’[2].

In order for his garden city vision come to fruition, Howard needed a large sum of money to purchase land for his experiment. He decided to depend on “gentlemen of responsible position and undoubted probity and honor” to fund the project[3]. The Garden Cities Association (later known as the Town and Country Planning Association or TCPA), founded by Howard, created First Garden City, Ltd. in 1899 to create the garden city of Letchworth[4]. However, these donors would collect interest on their investment if the garden city generated profits through rents or as Fishman calls the process, ‘philanthropic land speculation’[5]. Howard attempted to include working-class cooperative organizations, which included over two million members, but could not win their financial support[6]. Due to the fact that he had to rely solely on the wealthy investors of First Garden City, Howard had to make concessions to his plan, such as eliminating the cooperative ownership scheme with no landlords, short-term rent increases, and hiring architects who did not agree with his rigid design plans[7].

In 1904, Raymond Unwin, a noted architect and town planner, along with his partner Barry Parker, won the competition run by the First Garden City, Limited to plan Letchworth, an area 34 miles outside of London[8]. Unwin and Parker planned the town in the centre of the Letchworth estate with Howard’s large agricultural greenbelt surrounding the town and they shared Howard’s notion that the working class deserved better and more affordable housing options. However, the architects ignored Howard’s symmetrical design, instead replacing it with a more ‘organic’ design[9].

Letchworth slowly attracted more residents because it was able to attract manufacturers through low taxes, low rents and more space[10]. Despite Howard’s best efforts, the home prices in this garden city could not remain affordable for blue-collar workers to live in. The populations composed mostly of skilled middle-class workers. After a decade, the First Garden City became profitable and started paying dividends to its investors[11]. Even though many viewed Letchworth as a success, it did not immediately inspire government investment into the next line of garden cities.

In reference to the lack of government support for garden cities, Frederic James Osborn, a colleague of Howard and his eventual successor at the Garden City Association, recalled him saying, “The only way to get anything done is to do it yourself.”[12]. Likely in frustration, Howard purchased land at Welwyn at auction, with no money of his own, to house the second garden city in 1919[13]. He desperately and successfully persuaded his friends to loan him the money. The Welwyn Garden City Corporation was formed to Welwyn failed to truly exist as self-sustaining because of its proximity to London of 20 miles[14].

Even until the end of the 1930s, Letchworth and Welwyn remained as the only existing garden cities. Though Howard’s efforts did not lead to a string of garden cities, the movement did succeed in emphasizing the need for urban planning policies that eventually led to the New Town movement[15].

Garden cities

Howard organized the Garden City Association during 1899. Two garden cities were built using Howard's ideas: Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City, both in Hertfordshire, England. Howard's successor as chairman of the Garden City Association was Sir Frederic Osborn, who extended the movement to regional planning.[16]

The concept was adopted again in England after World War II, when the New Towns Act caused the development of many new communities based on Howard's egalitarian ideas.

The idea of the garden city was influential in the United States. Examples are: the Woodbourne neighborhood of Boston; Newport News, Virginia's Hilton Village; Pittsburgh's Chatham Village; Garden City, New York; Sunnyside, Queens; Jackson Heights, Queens; Forest Hills Gardens, also in the borough of Queens, New York; Radburn, New Jersey; Greenbelt, Maryland; Buckingham in Arlington County, Virginia; the Lake Vista neighborhood in New Orleans; Norris, Tennessee; Baldwin Hills Village in Los Angeles; and the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights. In Canada, the Ontario towns of Kapuskasing and Walkerville are, in part, garden cities.

In Argentina an example is Ciudad Jardín Lomas del Palomar, declared by the influential Argentinian professor of engineering, Carlos María della Paolera, initiator of "Día Mundial del Urbanismo" (World Urbanism Day), as the first Garden City in South America.

In Australia, the suburb of Colonel Light Gardens in Adelaide, South Australia, was designed according to garden city principles.[17] So too the town of Sunshine, which is now a suburb of Melbourne in Victoria.[18][19]

Garden city principles greatly influenced the design of colonial and post-colonial capitals during the early part of the 20th century. This is the case for New Delhi (designed as the new capital of British-ruled India after World War 1), of Canberra (capital of Australia established during 1913) and of Quezon City (established during 1939, capital of the Philippines 1948-76). The garden city model was also applied to numerous colonial hill stations, such as Da Lat in Vietnam (est. 1907) and Ifrane in Morocco (est. 1929).

In Bhutan's capitol city Thimphu the new plan, with the Principles of Intelligent Urbanism, is an organic response to the fragile ecology. Using sustainable concepts, it is a contemporary response to the Garden City concept.

The Garden City philosophy also influenced the Scottish urbanist, Sir Patrick Geddes, for the planning of Tel-Aviv, Israel during the 1920s, during the British Mandate. Geddes started his Tel Aviv plan during 1925 and submitted the final version during 1927, so all growth of this garden city during the 1930s was merely "based" on the Geddes Plan. Changes were inevitable.[20]

Garden suburbs

The concept of garden cities is to produce relatively economically independent cities with short commute times and the preservation of the countryside. Garden suburbs arguably do the opposite. Garden suburbs are built on the outskirts of large cities with no sections of industry and dependent on trains to London[21].

Following Unwin’s participation in the Letchworth garden city project in 1907, he moved on to work one of the first garden suburbs, Hampstead[22]. Years later, Unwin became very influential in government policy supporting garden suburbs as opposed to creating new independent cities[23]. Many now view Unwin as turning his back on the garden city movement.

Garden suburbs were not part of Howard's plan[24] and were actually a hindrance to garden city planning—- they were in fact almost the antithesis of Howard's plan, what he was trying to prevent. The suburbanization of London was an increasing problem which Howard attempted to solve with his garden city model, which attempted to end urban sprawl by the sheer inhibition of land development due to the land being maintained in trust, and the inclusion of agricultural areas on the city outskirts.[25]

Smaller developments were also inspired by the garden city philosophy and were modified to allow for residential "garden suburbs" without the commercial and industrial components of the garden city. They were built on the outskirts of cities, in rural settings. Some notable examples being, in London, Hampstead Garden Suburb and the 'Exhibition Estate' in Gidea Park and, in Liverpool, Wavertree Garden Suburb. The Gidea Park estate in particular was built during two main periods of activity, 1911, and 1934. Both resulted in some good examples of domestic architecture, by such architects as Wells Coates and Berthold Lubetkin. Thanks to such strongly conservative local residents associations as the Civic Society, both Hampstead and Gidea Park retain much of their original character.

One unique example of a garden suburb is the Humberstone Garden Suburb in the United Kingdom by the Humberstone Anchor Tenants association in Leicestershire and it is the only garden suburb ever to be built by the members of a workers co-operative; it remains intact to the present.[26] During 1887 the workers of the Anchor shoe company in Humberstone formed a workers cooperative and built 97 houses.

American architect Walter Burley Griffin was a proponent of the fashion and after arrival in Australia to design the national capitol Canberra, produced a number of Garden Suburb estates, most notably at Eaglemont with the Glenard and Mount Eagle Estates and the Ranelagh and Milleara Estates in Victoria.

Legacy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

Contemporary town-planning charters like New Urbanism and Principles of Intelligent Urbanism originated with this fashion. Presently there are many garden cities in the world. Most of them however have devolved to dormitory suburbs, which completely differ from what Howard attempted to create.

The Town and Country Planning Association recently[when?] marked its 108th anniversary by endorsing Garden City and Garden Suburb principles to be applied to the present New Towns and Eco-towns in the United Kingdom.

See also

Developments influenced by the Garden city movement:

- Bedford Park, London, United Kingdom

- Hellerau, Dresden, Germany

- Milton Keynes, England, United Kingdom

- St Helier, London, United Kingdom

- Tapiola, Finland

- Telford, United Kingdom

- Marino, Dublin, Ireland

- Reston, Virginia, United States

Related urban design concepts:

- Transition Towns

- European Urban Renaissance

- New Pedestrianism

- Transit Oriented Development

- Urban forest

- Principles of Intelligent Urbanism

- Soviet urban planning ideologies of the 1920s

References

- ^ Goodall, B. (1987) The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography. London: Penguin.

- ^ Howard, E. 1902, Garden Cities of To-morrow, 2nd edn, S. Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd., London. , p. 2-7

- ^ Fainstein, S. & Campbell, S. 2003, Readings in planning theory, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p.42

- ^ Hardy, D. 1999, 1899-1999, Town and Country Planning Association, London., p. 4

- ^ Fainstein, S. & Campbell, S. 2003, Readings in planning theory, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p.43

- ^ Fainstein, S. & Campbell, S. 2003, Readings in planning theory, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p.46

- ^ Fainstein, S. & Campbell, S. 2003, Readings in planning theory, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p.47

- ^ Hall, P. 2002, Cities of Tomorrow, 3rd edn, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p. 68

- ^ Fainstein, S. & Campbell, S. 2003, Readings in planning theory, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p.48

- ^ Fainstein, S. & Campbell, S. 2003, Readings in planning theory, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p.50

- ^ Hall, P. 2002, Cities of Tomorrow, 3rd edn, Blackwell, Malden, Mass., p. 100

- ^ Hall, P. & Ward, C. 1998, Sociable Cities: the Legacy of Ebenezer Howard, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester., p.45-47

- ^ Hardy, D. 1999, 1899-1999, Town and Country Planning Association, London., p. 8

- ^ Hall, P. & Ward, C. 1998, Sociable Cities: the Legacy of Ebenezer Howard, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester., p.46

- ^ Hall, P. & Ward, C. 1998, Sociable Cities: the Legacy of Ebenezer Howard, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester., p.52-53

- ^ History of the TCPA 1899-1999

- ^ City of Mitcham - History Pages

- ^ Victorian Heritage Database - HV MCKAY MEMORIAL GARDENS

- ^ Brimbank City Council Post-contact Cultural Heritage Study - 2000 Study Site N 068 - Albion - HO Selwyn Park

- ^ Webberley, Helen: Town-planning in a Brand New City, AAANZ Conference, Brisbane, 2008 and see http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com/.

- ^ Hall, P. & Ward, C. 1998, Sociable Cities: the Legacy of Ebenezer Howard, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester. p. 41

- ^ Hall, P. 2002, Cities of Tomorrow, 3rd edn, Blackwell, Malden, Mass. p. 104

- ^ Hall, P. 2002, Cities of Tomorrow, 3rd edn, Blackwell, Malden, Mass. p. 110-112

- ^ Hall, Peter. (1996). Cities of Tomorrow. Oxford: BlackWell Pub. chp.4

- ^ Design on the Land

- ^ "Humberstone Garden Suburb". Utopia-britannica.org.uk. Retrieved 2011-03-28.