Sudoku

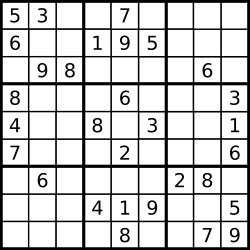

Sudoku (Japanese: 数独, romanized: sūdoku, ); /suːˈdoʊkuː/ soo-DOH-koo) is a logic-based,[1][2] combinatorial[3] number-placement puzzle. The objective is to fill a 9×9 grid with digits so that each column, each row, and each of the nine 3×3 sub-grids that compose the grid (also called "boxes", "blocks", "regions", or "sub-squares") contains all of the digits from 1 to 9. The puzzle setter provides a partially completed grid, which typically has a unique solution.

Completed puzzles are always a type of Latin square with an additional constraint on the contents of individual regions. For example, the same single integer may not appear twice in the same 9x9 playing board row or column or in any of the nine 3x3 subregions of the 9x9 playing board.[4]

The puzzle was popularized in 1986 by the Japanese puzzle company Nikoli, under the name Sudoku, meaning single number.[5] It became an international hit in 2005.[6]

History

Number puzzles appeared in newspapers in the late 19th century, when French puzzle setters began experimenting with removing numbers from magic squares. Le Siècle, a Paris-based daily, published a partially completed 9×9 magic square with 3×3 sub-squares on November 19, 1892.[7] It was not a Sudoku because it contained double-digit numbers and required arithmetic rather than logic to solve, but it shared key characteristics: each row, column and sub-square added up to the same number.

On July 6, 1886, Le Siècle's rival, La France, refined the puzzle so that it was almost a modern Sudoku. It simplified the 9×9 magic square puzzle so that each row, column and broken diagonals contained only the numbers 1–9, but did not mark the sub-squares. Although they are unmarked, each 3×3 sub-square does indeed comprise the numbers 1–9 and the additional constraint on the broken diagonals leads to only one solution.[8]

These weekly puzzles were a feature of French newspapers such as L'Echo de Paris for about a decade but disappeared about the time of World War I.[9]

According to Will Shortz, the modern Sudoku was most likely designed anonymously by Howard Garns, a 74-year-old retired architect and freelance puzzle constructor from Indiana, and first published in 1979 by Dell Magazines as Number Place (the earliest known examples of modern Sudoku). Garns' name was always present on the list of contributors in issues of Dell Pencil Puzzles and Word Games that included Number Place, and was always absent from issues that did not.[10] He died in 1989 before getting a chance to see his creation as a worldwide phenomenon.[10] It is unclear if Garns was familiar with any of the French newspapers listed above.

The puzzle was introduced in Japan by Nikoli in the paper Monthly Nikolist in April 1984[10] as Sūji wa dokushin ni kagiru (数字は独身に限る), which can be translated as "the digits must be single" or "the digits are limited to one occurrence." (In Japanese,"dokushin" means an "unmarried person".) At a later date, the name was abbreviated to Sudoku(數獨) by Maki Kaji (鍜治 真起, Kaji Maki), taking only the first kanji of compound words to form a shorter version.[10] In 1986, Nikoli introduced two innovations: the number of givens was restricted to no more than 32, and puzzles became "symmetrical" (meaning the givens were distributed in rotationally symmetric cells). It is now published in mainstream Japanese periodicals, such as the Asahi Shimbun.

Variants

Although the 9×9 grid with 3×3 regions is by far the most common, variations abound. Sample puzzles can be 4×4 grids with 2×2 regions; 5×5 grids with pentomino regions have been published under the name Logi-5; the World Puzzle Championship has featured a 6×6 grid with 2×3 regions and a 7×7 grid with six heptomino regions and a disjoint region. Larger grids are also possible. The Times offers a 12×12-grid Dodeka sudoku with 12 regions of 4×3 squares. Dell regularly publishes 16×16 Number Place Challenger puzzles (the 16×16 variant often uses 1 through G rather than the 0 through F used in hexadecimal). Nikoli offers 25×25 Sudoku the Giant behemoths. Sudoku-zilla[11] , a 100x100-grid was published in print in 2010.

Another common variant is to add limits on the placement of numbers beyond the usual row, column, and box requirements. Often the limit takes the form of an extra "dimension"; the most common is to require the numbers in the main diagonals of the grid also to be unique. The aforementioned Number Place Challenger puzzles are all of this variant, as are the Sudoku X puzzles in the Daily Mail, which use 6×6 grids.

A variant named "Mini Sudoku" appears in the American newspaper USA Today, which is played on a 6×6 grid with 3×2 regions. The object is the same as standard Sudoku, but the puzzle only uses the numbers 1 through 6.

Another variant is the combination of Sudoku with Kakuro on a 9 × 9 grid, called Cross Sums Sudoku, in which clues are given in terms of cross sums. The clues can also be given by cryptic alphametics in which each letter represents a single digit from 0 to 9. An excellent example is NUMBER+NUMBER=KAKURO which has a unique solution 186925+186925=373850. Another example is SUDOKU=IS*FUNNY whose solution is 426972=34*12558.

Killer Sudoku combines elements of Sudoku with Kakuro—usually, no initial numbers are given, but the 9×9 grid is divided into regions, each with a number that the sum of all numbers in the region must add up to and with no repeated numerals. These must be filled in while obeying the standard rules of Sudoku.

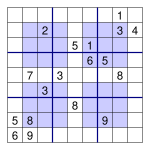

Hypersudoku is one of the most popular variants. It is published by newspapers and magazines around the world and is also known as "NRC Sudoku", "Windoku", "Hyper-Sudoku" and "4 Square Sudoku". The layout is identical to a normal Sudoku, but with additional interior areas defined in which the numbers 1 to 9 must appear. The solving algorithm is slightly different from the normal Sudoku puzzles because of the leverage on the overlapping squares. This overlap gives the player more information to logically reduce the possibilities in the remaining squares. The approach to playing is similar to Sudoku but with possibly more emphasis on scanning the squares and overlap rather than columns and rows.

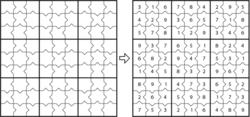

Puzzles constructed from multiple Sudoku grids are common. Five 9×9 grids which overlap at the corner regions in the shape of a quincunx is known in Japan as Gattai 5 (five merged) Sudoku. In The Times, The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald this form of puzzle is known as Samurai SuDoku. The Baltimore Sun and the Toronto Star publish a puzzle of this variant (titled High Five) in their Sunday edition. Often, no givens are to be found in overlapping regions. Sequential grids, as opposed to overlapping, are also published, with values in specific locations in grids needing to be transferred to others.

Str8ts shares the Sudoku requirement of uniqueness in the rows and columns but the third constraint is very different. Str8ts uses black cells (some with clue numbers) to divide the board into compartments. These must be filled with a set of numbers that form a 'straight', like the poker hand. A straight is a set of numbers with no gaps in them, such as '4,3,6,5' - and the order can be non-sequential. 9x9 is the traditional size but with suitable placement of black cells any size board is possible.

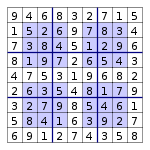

Alphabetical variations have emerged, sometimes called Wordoku; there is no functional difference in the puzzle unless the letters spell something. Some variants, such as in the TV Guide, include a word reading along a main diagonal, row, or column once solved; determining the word in advance can be viewed as a solving aid. A Wordoku might contain other words, other than the main word. Like in the example to the left, the words "Kari", "Park" and "Per" could also be found in the solution. This might be avoided by e.g. substituting the character "R" with e.g. a "Q".

A tabletop version of Sudoku can be played with a standard 81-card Set deck (see Set game). A three-dimensional Sudoku puzzle was invented by Dion Church and published in the Daily Telegraph in May 2005. There is a Sudoku version of the Rubik's Cube named Sudoku Cube.

There are many other variants. Some are different shapes in the arrangement of overlapping 9x9 grids, such as butterfly, windmill, or flower.[12] Others vary the logic for solving the grid. One of these is Greater Than Sudoku. In this a 3×3 grid of the Sudoku is given with 12 symbols of Greater Than (>) or Less Than (<) on the common line of the two adjacent numbers.[10] Another variant on the logic of solution is Clueless Sudoku, in which nine 9x9 Sudoku grids are themselves placed in a three-by-three array. The center cell in each 3x3 grid of all nine puzzles is left blank and form a tenth Sudoku puzzle without any cell completed; hence, "clueless".[12]

Mathematics of Sudoku

A completed Sudoku grid is a special type of Latin square with the additional property of no repeated values in any of the 9 blocks of contiguous 3×3 cells. The relationship between the two theories is now completely known, after Denis Berthier proved in his book The Hidden Logic of Sudoku (May 2007) that a first-order formula[clarification needed] that does not mention blocks (also called boxes or regions) is valid for Sudoku if and only if it is valid for Latin Squares (this property is trivially true for the axioms and it can be extended to any formula). (Citation taken from p. 76 of the first edition: "any block-free resolution rule is already valid in the theory of Latin Squares extended to candidates" – which is restated more explicitly in the second edition, p. 86, as: "a block-free formula is valid for Sudoku if and only if it is valid for Latin Squares").

The first known calculation of the number of classic 9×9 Sudoku solution grids was posted on the USENET newsgroup rec.puzzles in September 2003[13] and is 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 (sequence A107739 in the OEIS), or approximately 6.67 x 1021. This is roughly 1.2×10−6 times the number of 9×9 Latin squares. A detailed calculation of this figure was provided by Bertram Felgenhauer and Frazer Jarvis in 2005.[14] Various other grid sizes have also been enumerated—see the main article for details. The number of essentially different solutions, when symmetries such as rotation, reflection, permutation and relabelling are taken into account, was shown by Ed Russell and Frazer Jarvis to be just 5,472,730,538[15] (sequence A109741 in the OEIS).

The maximum number of givens provided while still not rendering a unique solution is four short of a full grid; if two instances of two numbers each are missing and the cells they are to occupy form the corners of an orthogonal rectangle, and exactly two of these cells are within one region, there are two ways the numbers can be assigned. Since this applies to Latin squares in general, most variants of Sudoku have the same maximum. The inverse problem—the fewest givens that render a solution unique—is unsolved, although the lowest number yet found for the standard variation without a symmetry constraint is 17, a number of which have been found by Japanese puzzle enthusiasts,[16][17] and 18 with the givens in rotationally symmetric cells. Over 48,000 examples of Sudokus with 17 givens resulting in a unique solution are known.

In 2010 mathematicians Paul Newton and Stephen DeSalvo of the University of Southern California showed that the arrangement of numbers in Sudoku puzzles are more random than the number arrangements in randomly generated 9x9 matrices. This is because the rules of Sudoku exclude some random arrangements that have an innate symmetry.[18]

Recent popularity

In 1997, New Zealander and retired Hong Kong judge Wayne Gould, then in his early 50s, saw a partly completed puzzle in a Japanese bookshop. Over six years he developed a computer program to produce puzzles quickly. Knowing that British newspapers have a long history of publishing crosswords and other puzzles, he promoted Sudoku to The Times in Britain, which launched it on 12 November 2004 (calling it Su Doku). The first letter to The Times regarding Su Doku was published the following day on 13 November from Ian Payn of Brentford, complaining that the puzzle had caused him to miss his stop on the tube.[19]

The rapid rise of Sudoku in Britain from relative obscurity to a front-page feature in national newspapers attracted commentary in the media and parody (such as when The Guardian's G2 section advertised itself as the first newspaper supplement with a Sudoku grid on every page).[20] Recognizing the different psychological appeals of easy and difficult puzzles, The Times introduced both side by side on 20 June 2005. From July 2005, Channel 4 included a daily Sudoku game in their Teletext service. On 2 August, the BBC's programme guide Radio Times featured a weekly Super Sudoku which features a 16×16 grid.

In the United States, the first newspaper to publish a Sudoku puzzle by Wayne Gould was The Conway Daily Sun (New Hampshire), in 2004.[21]

The world's first live TV Sudoku show, Sudoku Live, was a puzzle contest first broadcast on 1 July 2005 on Sky One. It was presented by Carol Vorderman. Nine teams of nine players (with one celebrity in each team) representing geographical regions competed to solve a puzzle. Each player had a hand-held device for entering numbers corresponding to answers for four cells. Phil Kollin of Winchelsea, England was the series grand prize winner taking home over £23,000 over a series of games. The audience at home was in a separate interactive competition, which was won by Hannah Withey of Cheshire.

Later in 2005, the BBC launched SUDO-Q, a game show that combines Sudoku with general knowledge. However, it uses only 4×4 and 6×6 puzzles. Four seasons were produced, before the show ended in 2007.

In 2006, a Sudoku website published songwriter Peter Levy's Sudoku tribute song,[22] but quickly had to take down the mp3 due to heavy traffic. British and Australian radio picked up the song, which is to feature in a British-made Sudoku documentary. The Japanese Embassy also nominated the song for an award, with Levy doing talks with Sony in Japan to release the song as a single.[23]

Sudoku software is very popular on PCs, websites, and mobile phones. It comes with many distributions of Linux. Software has also been released on video game consoles, such as the Nintendo DS, PlayStation Portable, the Game Boy Advance, Xbox Live Arcade, the Nook e-book reader, several iPod models, and the iPhone. In fact, just two weeks after Apple Inc. debuted the online App Store within its iTunes store on July 11, 2008, there were already nearly 30 different Sudoku games, created by various software developers, specifically for the iPhone and iPod Touch. One of the most popular video games featuring Sudoku is Brain Age: Train Your Brain in Minutes a Day!. Critically and commercially well received, it generated particular praise for its Sudoku implementation[24][25][26] and sold more than 8 million copies worldwide.[27] Due to its popularity, Nintendo made a second Brain Age game titled Brain Age2, which has over 100 new Sudoku puzzles and other activities.

In June 2008 an Australian drugs-related jury trial costing over A$1,000,000 was aborted when it was discovered that five of the twelve jurors had been playing Sudoku instead of listening to evidence.[28]. Also in Australia, realizing that English crossword puzzles in daily English language newspapers are not suitable mental exercises for people in the ethnic communities of non-English background, books have been written to popularize Sudoku among them and regular Sudoku columns have appeared in foreign language magazines and newspapers published by diverse ethnic communities of Australia's migrants since 2008.

Competitions

- The first World Sudoku Championship was held in Lucca, Italy, from March 10–12, 2006. The winner was Jana Tylová of the Czech Republic.[29] The competition included numerous variants.[30]

- The second World Sudoku Championship was held in Prague from March 28 to April 1, 2007.[31] The individual champion was Thomas Snyder of the USA. The team champion was Japan.[32]

- The third World Sudoku Championship was held in Goa, India, from April 14–16, 2008. Thomas Snyder repeated as the individual overall champion, and also won the first ever Classic Trophy (a subset of the competition counting only classic Sudoku). The Czech Republic won the team competition.[33]

- The fourth World Sudoku Championship was held in Žilina, Slovakia, from April 24–27, 2009. After past champion Thomas Snyder of USA won the general qualification, Jan Mrozowski of Poland emerged from a 36-competitor playoff to become the new World Sudoku Champion. Host nation Slovakia emerged as the top team in a separate competition of three-membered squads.[34]

- The fifth World Sudoku Championship was held in Philadelphia, USA from April 29 – May 2, 2010. Jan Mrozowski of Poland successfully defended his world title in the individual competition while Germany won a separate team event. The puzzles were written by Thomas Snyder and Wei-Hwa Huang, both past US Sudoku champions.[35]

- In the United States, The Philadelphia Inquirer Sudoku National Championship has been held three times, each time offering a $10,000 prize to the advanced division winner and a spot on the U.S. National Sudoku Team traveling to the world championships. Puzzlemaster Will Shortz has served as tournament host. The winners of the event have been Thomas Snyder (2007),[36] Wei-Hwa Huang (2008), and Tammy McLeod (2009).[37] In the most recent event, the third place finalist in the advanced division, Eugene Varshavsky, performed quite poorly onstage after setting a very fast qualifying time on paper, which caught the attention of organizers and competitors including past champion Thomas Snyder who requested organizers reconsider his results due to a suspicion of cheating.[38] Following an investigation and a retest of Varshavsky, the organizers disqualified him and awarded Chris Narrikkattu third place.[39]

See also

- 36 cube

- Algorithmics of Sudoku

- Futoshiki

- Hidato

- Kakuro

- KenKen

- List of Nikoli puzzle types

- List of Sudoku terms and jargon

- Logic puzzle

- Mathematics of Sudoku

- Nonogram (aka Paint by numbers, O'ekaki)

- Str8ts sequential numbers

Notes

- ^ Arnoldy, Ben. "Sudoku Strategies". The Home Forum. The Christian Science Monitor.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Schaschek, Sarah (March 22, 2006). "Sudoku champ's surprise victory". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ Lawler, E.L. (1985). The Traveling Salesman problem – A Guided Tour of Combinatorial Optimization. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471904139.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sudoku.name

- ^ Brian Hayes (2006). Unwed Numbers. Vol. 94. American Scientist. pp. 12–15.

- ^ So you thought Sudoku came from the Land of the Rising Sun ... The puzzle gripping the nation actually began at a small New York magazine by David Smith The Observer, Sunday May 15, 2005 Accessed June 13, 2008

- ^

Boyer, Christian (2006). "Supplément de l'article « Les ancêtres français du sudoku »" (PDF). Pour la Science: 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Boyer, Christian (2007). "Sudoku's French ancestors". Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Malvern, Jack (2006-06-03). "Les fiendish French beat us to Su Doku". Times Online. London. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ^ a b c d e

Pegg, Ed, Jr. (2005-09-15). "Ed Pegg Jr.'s Math Games: Sudoku Variations". MAA Online. The Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eisenhauer, William (2010). Sudoku-zilla. CreateSpace. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-45-151049-2.

- ^ a b "www.janko.at".

- ^ "Combinatorial question on 9×9". Google newsgroups archive. Retrieved September 2003.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Jarvis, Frazer (2006-07-31). "Sudoku enumeration problems". Frazer Jarvis's home page. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ Jarvis, Frazer (2005-09-07). "There are 5472730538 essentially different Sudoku grids ... and the Sudoku symmetry group". Frazer Jarvis's home page. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "プログラミングパズルに関心のある人は雑談しましょう". プログラミングパズル雑談コーナー / Programming Puzzle Idle Talk Corner (in Japanese). Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ Royle, Gordon. "Minimum Sudoku". Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ Paul K. Newton and Stephen A. DeSalvo. The Shannon entropy of Sudoku matrices Proceedings of the Royal Society A. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2009.0522.

- ^ Timesonline.co.uk

- ^ "G2, home of the discerning Sudoku addict". The Guardian. London: Guardian Newspapers Limited. 2005-05-13. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ^ Correction attached to "Inside Japan’s Puzzle Palace", New York Times, March 21, 2007

- ^ "Sudoku the song, by Peter Levy". Sudoku.org.uk. 2006-08-17. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Hit Song Has the Numbers". The Herald Sun. 2006-08-17. Retrieved 2008-10-05. [dead link]

- ^ Gamerankings.com

- ^ Gamespot.com

- ^ IGN.com

- ^ Gamespot.com

- ^ Knox, Malcolm (2008-06-11). "The game's up: jurors playing Sudoku abort trial". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ^ "Sudoku title for Czech accountant" (Free). BBC NEWS. 2006-03-11. Retrieved 2006-09-11.

- ^ "World Sudoku Championship 2006 Instructions Booklet" (PDF). BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Report on the 8th General Assembly of the World Puzzle Federation" (Free). WPF. 2006-10-30. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

- ^ "Thomas Snyder wins World Sudoku Championship". US Puzzle Team. 2007-03-31. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ Harvey, Michael (2008-04-17). "It's a puzzle but sun, sea and beer can't compete with Sudoku for British team". TimesOnline. London. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ Malvern, Jack (2009-04-27). "Su Doku battle goes a little off the wall". TimesOnline. London. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ^ "Pole, 23, repeats as Sudoku world champ". PhillyInquirer. 2009-05-02. Retrieved 2009-05-03. [dead link]

- ^ "Thomas Snyder, World Sudoku champion" (Free). Philadelphia Inquirer. 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ^ "Going for 2d, she wins 1st" (Free). Philadelphia Inquirer. 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2009-10-27. [dead link]

- ^ "Possible cheating probed at Sudoku National Championship" (Free). Philadelphia Inquirer. 2009-10-27. Retrieved 2009-10-27. [dead link]

- ^ "3rd-place winner disqualified in sudoku scandal" (Free). Philadelphia Inquirer. 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2009-11-24. [dead link]

Further reading

- Delahaye, Jean-Paul, "The Science Behind Sudoku", Scientific American magazine, June 2006.

- Kim, Scott, "The Science of Sudoku", 2006

- Provan, J. Scott, "Sudoku: Strategy Versus Structure", American Mathematical Monthly, October 2009. Published also as a University of North Carolina technical report UNC/STOR/08/04, 2008.

External links

- Template:Dmoz – An active listing of Sudoku links.

- 'Father of Sudoku' puzzles next move BBC