Heathenry in the United States

Ásatrú (from Icelandic for "Æsir faith", pronounced [auːsatruː], in Old Norse [aːsatruː]) in the United States is a form of Germanic Neopaganism, in particular inspired by the Norse paganism as described in the Eddas and as practiced prior to the Christianization of Scandinavia.

There are three national organizations of Nordic Paganism in the United States, Ásatrú Alliance, Ásatrú Folk Assembly and The Troth, besides numerous smaller or regional associations. Historically, the main dispute between these has generally centered on the interpretation of "Nordic heritage" as either something cultural, or as something genetic or racial ("metagenetic"). In the internal discourse within American Asatru, this cultural/racial divide has long been known as "universalist" vs. "folkish" Asatru.[1]

The Troth takes the "universalist" position, claiming Asatru as a synonym for "Northern European Heathenry" taken to comprise "many variations, names, and practices, including Theodism, Irminism, Odinism, and Anglo-Saxon Heathenry". In the UK, Germanic Neopaganism is more commonly known as Odinism or as Heathenry. This is mostly a matter of terminology, and US Asatru may be equated with UK Odinism for practical purposes, as is evident in the short-lived International Asatru-Odinic Alliance of folkish Asatru/Odinist groups.

Terminology

Ásatrú is an Icelandic (and equivalently Old Norse) term consisting of two parts. The first is Ása-, genitive of Áss, denoting one of the group of Norse heathen gods called Æsir.[2] The second part, trú, means "faith, word of honour; religious faith, belief"[3] (archaic English troth "loyalty, honesty, good faith"). Thus, Ásatrú means "belief / faith in the Æsir / gods".

The term is the Old Norse/Icelandic translation of Asetro, a neologism coined in the context of 19th century romantic nationalism, used by Edvard Grieg in his 1870 opera Olaf Trygvason. The use of the term Ásatrú for Germanic heathenism preceding 19th century revivalist movements is therefore an anachronism.

Ásatrúarmaður (plural Ásatrúarmenn), the term used to identify those who practice Ásatrú is a compound with maður (Old Norse maðr) "man".[4] In English usage, the genitive Asatruar "of Æsir faith" is often used on its own to denote adherents (both singular and plural).

Differences from Scandinavian and German usage

There are two main strains contemporary Germanic Paganism known as Ásatrú, originating near-simultaneously in Iceland (Ásatrúarfélagið, 1972) and the USA (Asatru Free Assembly, 1974). While the Scandinavian branch emphasizes pantheist spirituality rooted in medieval and contemporary Scandinavian folklore, the American branch postulates a "native religion of the peoples of Northern Europe" reaching back into the paleolithic.[5] In Germany, the term Asatru is used in the wider sense of Germanic neopaganism.

As Ásatrú implies a focus on polytheistic belief in the Æsir usage of the term in Scandinavia has declined somewhat. In Scandinavia, forn sed / forn siðr "old custom", Nordisk sed "Nordic custom" or hedensk sed / heiðinn siður "heathen custom" are preferred.[6] In both the Anglosphere and German-speaking Europe, it is widely used interchangeably with other terms for Germanic Neopaganism.[7]

There are notable differences of emphasis between Ásatrú as practiced in the USA and in Scandinavia. According to Strmiska and Sigurvinsson (2005), American Asatruar tend to prefer a more devotional form of worship and a more emotional conception of the Nordic gods than Scandinavian practitioner, reflecting the parallel tendency of highly emotional forms of Christianity prevalent in the United States .[8]

History

In the early 1970s, Stephen McNallen, a former U.S. Army Airborne Ranger, began publishing a newsletter titled The Runestone. He also formed an organization called the Ásatrú Free Assembly, which was later renamed the Ásatrú Folk Assembly which is still extant. Else Christensen's Odinism, which is sometimes identified with the term Ásatrú, originated around the same period.

In 1986, the "folkish vs. universalist" dispute and the dispute over the stance of Ásatrú towards white supremacism escalated, resulting in the breakup of the Asatru Free Assembly. The universalist branch reformed as The Troth, while the folkish branch became the Ásatrú Alliance (AA). McNallen re-founded his own organisation as the Ásatrú Folk Assembly (AFA) in 1994.

In 1997, the Britain based Odinic Rite (OR) founded a US chapter (ORV). This means that folkish Asatru is represented by three major organizations in the US, viz. AA, AFA and OR. The three groups have attempted to collaborate within an International Asatru-Odinic Alliance from 1997 to 2002, but was dissolved again in 2001 as a result of internal factional disputes.

Ásatrú Alliance, headed by Valgard Murray, publishes the "Vor Tru" newsletter. The Ásatrú Alliance held its 25th annual "Althing" gathering in 2005.[9]

Beliefs and practice

Ásatrú groups and the individual Ásatrúarmenn have no standard means of practice.

The US Asatru Folk Assembly defines it as "an expression of the native, pre-Christian spirituality of Europe."

Blót

Many Ásatrú groups celebrate with Blóts. Historically, the Blót was an event that focused on a communal sacrifice at various times of the year for a number of purposes. Families and extended family organizations would gather to participate in the communal event.

Modern Blóts are celebrated several times during the year. Ásatrú communities (kindreds, hearths, mots) have different approaches to the frequency of Blóts and their means of celebrating them.

Sumbel

Besides the blót, key among the ritual structures of Ásatrú as developed by McNallen and Stine is the sumbel, a drinking-ritual in which a drinking horn full of mead or ale is passed around and a series of toasts are made, first to the Aesir, then to other supernatural beings, then to heroes or ancestors, and then to others. Participants make also make boasts of their own deeds, or oaths or promises of future actions. Words spoken during the sumbel are considered and consecrated, becoming part of the destiny of those assembled.

Goðar

A Goði or Gothi (plural goðar) is the historical Old Norse term for a priest and chieftain in Norse paganism. Gyðja signifies a priestess. Goði literally means "speaker for the gods", and is used to denote the priesthood or those who officiate over rituals in Ásatrú. Several groups, most notably the Troth have organized clergy programs.[10] However, there is no universal standard for the Goðar amongst organizations, and the title is usually only significant to the particular group with whom they work.[11]

Kindred

A Kindred is a local worship group in Ásatrú. Other terms used are garth, stead, sippe, skeppslag and others. Kindreds are usually grassroots groups which may or may not be affiliated with a national organization like the Ásatrú Folk Assembly, the Ásatrú Alliance, or the Troth. Kindreds are composed of hearths or families as well as individuals, and the members of a Kindred may be related by blood or marriage, or may be unrelated. The kindred often functions as a combination of extended family and religious group. Membership is managed by the assent of the group.[12]

Kindreds usually have a recognized Goði to lead religious rites, while some other kindreds function more like modern corporations. Although these Goði need only be recognized by the kindred itself and may not have any standing with any other Kindred.

Related movements

Theodism

Theodism, or Þéodisc Geléafa (Old English: "tribal belief") is thought by some to be a variant or sister movement of US Ásatrú. Theodsmen themselves do not consider Theodism as a variant of Asatru and contend that the two religions are very different.[13][14] The term Theodism encompasses Norman, Angle, Continental Saxon, Frisian, Jutish, Gothic, Alemannic, Swedish, Danish and other tribal variants. Þéodisc is the adjective of þéod "people, tribe", cognate to Dutch/deutsch.

While having some commonalities with the Ásatrú movement following McNallen, Theodism primarily derived its origins as a reaction to Wicca. In 1971, Garman Lord and other practitioners of Gardnerian Wicca founded the The Coven Witan of Anglo-Saxon Wicca.[15] Theodism is focused on the lore, beliefs and social structure - particularly the concept of thew (Old English þeaw) or "customary law" - of various specific Germanic tribes. The main distinction between Theodism and other modern manifestations of Germanic Neopaganism along with pre-Christian religions, the Theodish are also attempting to reconstruct aspects of pre-Christian Germanic social order (including sacral kingship). In general, Théodish religious festivities are referred to as 'fainings' (meaning 'celebration'). As a rule, there are two sorts of rituals; blót and symbel. Húsel is technically part of blót.[16] Symbel is normally held after the feast, inasmuch as it is custom not to have food present.[17]

Garman Lord formed the Witan Theod in Watertown, New York, in 1976. A few years later, the Moody Hill Theod emerged as an offshoot of the Witan Theod.[18] In 1988 the Winland Rice was formed as an umbrella organization of Theodish groups.[18] Gert McQueen, Elder and Redesman of the Ring of Troth, was successful in lobbying the U.S. Army Chaplain’s Corps to adopt guidelines for recognizing heathen religions and Theodish belief in particular.

The Winland Rice dissolved in 2002. In 2004, Garman Lord stated that the religion of Theodism does not work in practice, dissolving Gering Theod and declaring Theodism as defunct[citation needed]. Several groups that have continued to call themselves Theodish. Axenthof Thiad originated in the early 1990s as the Fresena Thiad and part of the Winland Rice.[19] In 2005, Gerd Forsta Axenthoves changed the name to Axenthof Thiad.[20] Eric Wodening founded Englatheod in July 2007, while Sweartfenn Theod was founded, by Jeffrey Runokivi, in December 2007. Both groups practice Anglo-Saxon Theodism, and have members that have belonged to both the Winland Rice and the Ealdriht.[21] In New York, the New Normannii Reik of Theodish Belief was founded in 1997 and is led by Dan Halloran[22] ,[23] but in 2009 many members split off and formed the Arfstoll Church of Theodish Belief, White Marsh Theod, and Álfröðull þjóð.

One famous follower of Theodism is New York City Councilman Daniel J. Halloran. [24]

Fellowship of Anglo-Saxon Heathenry

The Fellowship of Anglo-Saxon Heathenry or Geferræden Fyrnsidu (GFS), is a Germanic Neopagan organization founded in the USA in 2001. It serves as a "church" or church-like institution fostering the reconstructed religion of the pagan Anglo-Saxons, known as Fyrnsidu. The group's website places itself in the "tribalist" category, taking the term Anglo-Saxon as a linguistic or cultural rather than a racial concept.

Politics and controversies

Ásatrú organizations have memberships which span the entire political and spiritual spectrum. There is a history of political controversy within organized US Ásatrú, mostly surrounding the question of how to deal with such adherents as place themselves in a context of the far right and white supremacy, notably resulting in the fragmentation of the Asatru Free Assembly in 1986.

Externally, political activity on the part of Ásatrú organizations has surrounded campaigns against alleged religious discrimination, such as the call for the introduction of an Ásatrú "emblem of belief" by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs to parallel the Wiccan pentacle granted to the widow of Patrick Stewart in 2006.

Folkish Asatru, Universalism and racialism

Some groups identifying as Ásatrú have been associated with neo-Nazi and "white power" movements.[25] (see Wotanism for more details) This was notably an issue in the 1980s, when the Asatru Free Assembly disintegrated as a result of tensions between the racist and the non-racist factions[citation needed].

Today, the three largest US American Ásatrú organizations have specifically denounced any association with racist groups.[26][27][28] A dividing issue is whether a person is "Folkish", meaning that an emphasis on ancestry and ancestor worship is a part of their belief system.

Discrimination charges

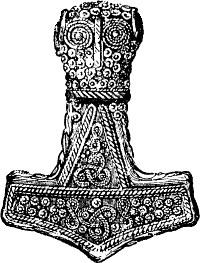

Inmates of the "Intensive Management Unit" at Washington State Penitentiary who are adherents of Ásatrú in 2001 were deprived of their Thor's Hammer medallions.[29] In 2007, a federal judge confirmed that Ásatrú adherents in US prisons have the right to possess a Thor’s Hammer pendant. An inmate sued the Virginia Department of Corrections after he was denied it while members of other religions were allowed their medallions.[30]

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs does not list any Ásatrú symbols as available emblems of belief for placement on government headstones and markers.[31] According to federal guidelines, only approved religious symbols — of which there are 38 — can be placed on government headstones or memorial plaques. Ásatrú Folk Assembly have demanded such a symbol.

In the Georgacarakos v. Watts case Peter N. Georgacarakos filed a pro se civil-rights complaint in the United States District Court for the District of Colorado against 19 prison officials for "interference with the free exercise of his Ásatrú religion" and "discrimination on the basis of his being Ásatrú".[32]

See also

- Germanic Neopaganism

- Ásatrú holidays

- Asatru in Germany and Austria

- Ásatrúarfélagið

- Neopaganism in the UK

- Heathenry in Canada

- Norse mythology

- Polytheistic reconstructionism

Notes

- ^ Strmiska and Sigurvinsson (2005), pp. 134f.

- ^ Zoega (1910): "one of the old heathen gods in general, or especially one of the older branch, in opposition to the younger ones (the Vanir)"[1]

- ^ Zoega (1910)

- ^ Irrespective of sex. [2], see Mannaz.

- ^ "Asatru reflects the deeper religiosity common to virtually all the nations of Europe." (Asatru Folk Assembly); " Ásatrú is thousands of years old. its beginnings are lost in prehistory, but as an organized system, it is older by far than Christianity. Strictly speaking, since Ásatrú is the religion which springs from the specific spiritual beliefs of the Northern Europeans, it is as old as this branch of the human race, which came into being 40,000 years ago." (Asatru Alliance)

- ^ "We prefer to refer to our faith as 'den forna seden' (The Old Way) rather than Asatru." (Sveriges Asatrosamfund)

- ^ Linzie, Bil (July 2003). "Germanic Spirituality" (PDF). Retrieved February 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "American Nordic Pagans want to feel an intimate relationship with their gods, not unlike evangelical attitudes towards Jesus. Icelandic Asatruar, by contrast, are more focused on devotion to their past cultural heritage rather than to particular gods." Strmiska and Sigurvinsson (2005), p. 165.

- ^ Murray, Valgard. "AlThing 25 Report". Retrieved February 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Information regarding the Troth's clergy program can be found on their official website here: [3]

- ^ Murray, Valgard. "The Role of the Gothar in the Asatru Community". Retrieved February 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Murray, Valgard. "The Asatru Kindred". Retrieved February 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://gamall-steinn.org/theod/gl-theod-asatru.htm

- ^ http://homepage.mac.com/mossmuncher/Sweartfenn_Theod/articles/articles/asatruandtheodism.html

- ^ Garman Lord, "The Evolution of Þéodisc Belief: Part I" Theod Magazine, Lammas, 1995

- ^ Swain Wodening, p. 100

- ^ Garman Lord, p. 27

- ^ a b Garman Lord, "The Evolution of Þéodisc Belief: Part II" Theod Magazine, Lammas, 1995

- ^ http://www.axenthof.org

- ^ http://www.axenthof.org/aboutus.html

- ^ http://swainblog.englatheod.org/?p=36

- ^ Tanner, Jeremy (2009), "City's First 'Heathen' Council Member", WPIX, retrieved 2009-11-24

- ^ Lee, Jennifer (2009-11-02), "Candidate's Religion Is Point of Contention in Queens Race", New York Times, City Room Blog, retrieved 2009-11-24

{{citation}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ Buettner, Russ; Rashbaum, William K. (2011-01-25). "Evidence Is Elusive on Charge of a Blizzard Slowdown". The New York Times.

- ^ Gardell, Matthias (2003). Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Duke University Press. pp. 269–283. ISBN 0822330717.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help) - ^ From the Asatru Alliance's Bylaws: "The Alliance is apolitical; it is not a front for, nor shall it promote any political views of the 'Right' or 'Left'. Our Sacred temples, groves and Moots shall remain free of any political manifestations." [4]

- ^ From the Asatru Folk Assembly's Bylaws: "The belief that spirituality and ancestral heritage are related has nothing to do with notions of superiority. Ásatrú is not an excuse to look down on, much less to hate, members of any other race. On the contrary, we recognize the uniqueness and the value of all the different pieces that make up the human mosaic." [5]

- ^ From The Troth's Bylaws: "Discrimination on the basis of race, gender, ethnic origin, or sexual orientation shall not be practiced by the Troth or any affiliated group, whether in membership decisions or in conducting any of its activities." [6]

- ^ Walla Walla's Suppression of Religious Freedom[unreliable source?]

- ^ First Amendment Center: Va. inmate can challenge denial of Thor's Hammer

- ^ Available Emblems of Belief for Placement on Government Headstones and Markers - Department of Veterans Affairs

- ^ Georgacarakos v. Watts

References

- Strmiska, M. and Sigurvinsson, B. A. , "Asatru: Nordic Paganism in Iceland and America" in: Strmiska (ed.), Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives (2005), ISBN 9781851096084, 127-180.

- Lord, Garman (2000). The Way of the Heathen: A Handbook of Greater Theodism. Theod. ISBN 1-929340-01-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - O'Halloran, Dan (2005). Thewbok: A Handbook of Theodish Thew. ISBN 0-9777610-0-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Kaplan, Jeffrey, "Odinism and Ásatrú", chapter 3 of Radical religion in America: millenarian movements from the far right to the children of Noah, Syracuse University Press, 1997, ISBN 9780815603962, pp. 69–99.

External links

- Ásatrú (Germanic Paganism) - ReligionFacts

- Asatru (Norse Heathenism) - AltReligion

- Ásatrú (Norse Heathenism) -Religioustolerance

- The Odinist/Asatru Library (pdf. files)

- Ravencast - The Only Asatru Podcast - Interviews and 101 Information

- Theodish Belief - General information about Theodism

- Organizations