Coral bleaching

Coral bleaching is the whitening of corals, due to stress-induced expulsion or death of their symbiotic protozoa, zooxanthellae, or due to the loss of pigmentation within the protozoa.[1] The corals that form the structure of the great reef ecosystems of tropical seas depend upon a symbiotic relationship with unicellular flagellate protozoa, called zooxanthellae, that are photosynthetic and live within their tissues. Zooxanthellae give coral its coloration, with the specific color depending on the particular clade. Under stress, corals may expel their zooxanthellae, which leads to a lighter or completely white appearance, hence the term "bleached".[2]

Once bleaching begins, it tends to continue even without continuing stress. If the coral colony survives the stress period, zooxanthellae often require weeks to months to return to normal density.[3] The new residents may be of a different species. Some zooxanthellae and coral species are more resistant to stress than others.

Cause

Bleaching occurs when the conditions necessary to sustain the coral's zooxanthellae cannot be maintained.[4] Any environmental trigger that affects the coral's ability to supply the zooxanthellae with nutrients for photosynthesis (carbon dioxide, ammonium) will lead to expulsion.[4] This process is a "downward spiral", whereby the coral's failure to prevent the division of zooxanthellae leads to ever-greater amounts of the photosynthesis-derived carbon to be diverted into the algae rather than the coral. This makes the energy balance required for the coral to continue sustaining its algae more fragile, and hence the coral loses the ability to maintain its parasitic control on its zooxanthellae.[4]

Triggers

Coral bleaching is a vivid sign of corals responding to stress, which can be induced by any of:

- increased (most commonly), or reduced water temperatures[5][6]

- increased solar irradiance (photosynthetically active radiation and ultraviolet band light)[7]

- changes in water chemistry (in particular acidification)[8][9]

- starvation caused by a decline in zooplankton[10]

- increased sedimentation (due to silt runoff)

- pathogen infections

- changes in salinity

- wind[6]

- low tide air exposure[6]

- cyanide fishing[11]

Temperature change

Temperature change is the most common cause of coral bleaching.[5]

Large coral colonies such as Porites are able to withstand extreme temperature shocks, while fragile branching corals such as table coral are far more susceptible to stress following a temperature change.[12] Corals consistently exposed to low stress levels may be more resistant to bleaching.[citation needed]

Factors that influence the outcome of a bleaching event include stress-resistance which reduces bleaching, tolerance to the absence of zooxanthellae, and how quickly new coral grows to replace the dead. Due to the patchy nature of bleaching, local climatic conditions such as shade or a stream of cooler water can reduce bleaching incidence. Coral and zooxanthellae health and genetics also influence bleaching.[13]

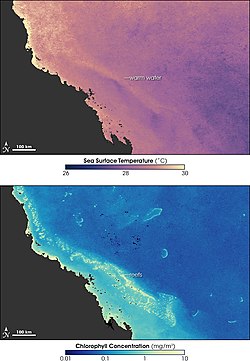

Monitoring reef sea surface temperature

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors for bleaching "hot spots", areas where sea surface temperature rises 1 °C (34 °F) or more above the long-term monthly average. This system detected the worldwide 1998 bleaching event,[14][15] that corresponded to an El Niño. NOAA also uses a satellite with 50k resolution at night, which covers a large area and does not detect the maximum sea surface temperatures occurring usually around noon.[citation needed]

Changes in ocean chemistry

Increasing ocean acidification likely exacerbates the bleaching effects of thermal stress.[citation needed]

Infectious disease

Infectious bacteria of the species Vibrio shiloi are the bleaching agent of Oculina patagonica in the Mediterranean Sea, causing this effect by attacking the zooxanthellae.[17][18] V. shiloi is infectious only during warm periods. Elevated temperature increases the virulence of V. shiloi, which then become able to adhere to a beta-galactoside-containing receptor in the surface mucus of the host coral.[18][19] V. shiloi then penetrates the coral's epidermis, multiplies, and produces both heat-stable and heat-sensitive toxins, which affect zooxanthellae by inhibiting photosynthesis and causing lysis.

During the summer of 2003, coral reefs in the Mediterranean Sea appeared to gain resistance to the pathogen, and further infection was not observed.[20] The main hypothesis for the emerged resistance is the presence of symbiotic communities of protective bacteria living in the corals. The bacterial species capable of lysing V. shiloi had not been identified as of 2011.

Impact

In the 2012-2040 period, coral reefs are expected to experience more frequent bleaching events. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sees this as the greatest threat to the world's reef systems.[21][22][23][24]

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef along the coast of Australia experienced bleaching events in 1980, 1982, 1992, 1994, 1998, 2002, and 2006.[24] While most areas recovered with relatively low levels of coral death, some locations suffered severe damage, with up to 90% mortality.[8] The most widespread and intense events occurred in the summers of 1998 and 2002, affecting about 42% and 54% of reefs, respectively.[25][26]

The IPCC's moderate warming scenarios (B1 to A1T, 2°C by 2100, IPCC, 2007, Table SPM.3, p. 13[27]) forecast that corals on the Great Barrier Reef are very likely to regularly experience summer temperatures high enough to induce bleaching.[25]

Other areas

Other coral reef provinces have been permanently damaged by warm sea temperatures, most severely in the Indian Ocean. Up to 90% of coral cover has been lost in the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Kenya and Tanzania and in the Seychelles.[28]

Evidence from extensive research in the 1970s of thermal tolerance in Hawaiian corals and of oceanic warming led researchers in 1990 to predict mass occurrences of coral bleaching throughout Hawaii. Major bleaching occurred in 1996 and in 2002.[29]

Coral in the south Red Sea does not bleach despite summer water temperatures up to 34°C.[citation needed]

Significant bleaching occurred in the Mediterranean Sea in 1996.[citation needed]

See also

Notes

- ^ Dove SG, Hoegh-Guldberg O (2006). "Coral bleaching can be caused by stress. The cell physiology of coral bleaching". In Ove Hoegh-Guldberg; Jonathan T. Phinney; William Skirving; Joanie Kleypas (ed.). Coral Reefs and Climate Change: Science and Management. [Washington]: American Geophysical Union. pp. 1–18. ISBN 0-87590-359-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Hoegh-Guldberg O (1999). "Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world's coral reefs" (PDF). Mar. Freshwater Res. 50: 839–66. doi:10.1071/MF99078.

- ^ Jokiel 1978

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1002/bies.200900182, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1002/bies.200900182instead. - ^ a b "REEF 'AT RISK IN CLIMATE CHANGE'". Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Anthony, K. 2007; Berkelmans

- ^ Fitts 2001

- ^ a b Johnson, Johanna E; Marshall, Paul A (2007). Climate change and the Great Barrier Reef : a vulnerability assessment. Townsville, Qld.: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. ISBN 9781876945619.

- ^ Hoegh-Guldberg O, Mumby PJ, Hooten AJ; et al. (2007). "Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification". Science. 318 (5857): 1737–42. doi:10.1126/science.1152509. PMID 18079392.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Starving Ocean: Mass Coral Bleaching

- ^ JONES, R.J. & O. HOEGH-GULDBERG. (1999). Effects of cyanide on coral photosynthesis: implications for identifying the cause of coral bleaching and for assessing the environmental effects of cyanide fishing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 177: 83–91

- ^ Baird and Marshall 2002

- ^ Marshall, Paul; Schuttenberg, Heidi (2006). A Reef Manager’s Guide to Coral Bleaching. Townsville, Australia: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority,. ISBN 1-876945-40-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "NOAA Hotspots".

- ^ "Pro-opinion of NOAA Hotspots".

- ^ Ryan Holl (17 April 2003). papers/Bioerosion.htm "Bioerosion: an essential, and often overlooked, aspect of reef ecology". Iowa State University. Retrieved 2 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Kushmaro, A.; Loya, Y.; Fine, M.; Rosenberg, E. (1996). "Bacterial infection and coral bleaching". Nature. 380 (6573): 396. doi:10.1038/380396a0.

- ^ a b Rosenberg E, Ben Haim Y (2002). "Microbial Diseases of Corals and Global Warming". Environ. Microbiol. 4 (6): 318–26. doi:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00302.x. PMID 12071977.

- ^ Sutherland KP, Porter J, Torres C (2004). "Disease and Immunity in Caribbean and Indo-pacific Zooxanthellate Corals". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 266: 273–302. doi:10.3354/meps266273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reshef L, Koren O, Loya Y, Zilber-Rosenberg I, Rosenberg E (2006). "The coral probiotic hypothesis". Environ. Microbiol. 8 (12): 2068–73. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01148.x. PMID 17107548.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ IPCC (2007). "Summary for policymakers". In Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE (ed.). Climate Change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–22. ISBN 0-521-70597-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Fischlin A, Midgley GF, Price JT, Leemans R, Gopal B, Turley C, Rounsevell MDA, Dube OP, Tarazona J, Velichko AA (2007). "Ch 4. Ecosystems, their properties, goods and services". In Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE (ed.). Climate Change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–72. ISBN 0-521-70597-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nicholls RJ, Wong PP, Burkett V, Codignotto J, Hay J, McLean R, Ragoonaden S, Woodroffe CD (2007). "Ch 6. Coastal systems and low-lying areas". In Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE (ed.). Climate Change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 315–57. ISBN 0-521-70597-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hennessy K, Fitzharris B, Bates BC, Harvey N, Howden M, Hughes L, Salinger J, Warrick R (2007). "Ch 11. Australia and New Zealand". In Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE (ed.). Climate Change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 507–40. ISBN 0-521-70597-5.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Done T, Whetton P, Jones R, Berkelmans R, Lough J, Skirving W, Wooldridge S (2003). Global Climate Change and Coral Bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef (PDF). Queensland Government Department of Natural Resources and Mines. ISBN 0-642-32220-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn-status=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berkelmans R, De'ath G, Kininmonth S, Skirving WJ (2004). "A comparison of the 1998 and 2002 coral bleaching events on the Great Barrier Reef: spatial correlation, patterns, and predictions" (PDF). Coral Reefs. 23 (1): 74–83. doi:10.1007/s00338-003-0353-y.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ IPCC (2007). "Summary for policymakers". In Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Tignor M, Miller HL (ed.). Climate change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–18.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link). - ^ N. Middleton, Managing the Great Barrier Reef (Geography Review, January 2004)

- ^ Hokiel, Paul J. "Climate Change and Hawaii's Coral Reefs" (PDF). Hawaii Coral Reef Monitoring and Assessment Program. US Fish and Wildlife Service.

External links

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority information on bleaching.

- ReefBase: a global information system on coral reefs.

- More details on coral bleaching, causes and effects.

- Travellers Impressions

- The Link between Overfishing and Mass Coral Bleaching

- Discussion on Overfishing and Coral Bleaching

- Social & Economic Costs of Coral Bleaching from "NOAA Socioeconomics" website initiative

- Microdocs: Coral bleaching

- Coral Bleaching at Maro Reef, September 2004