Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Thomas Murray, c. 1687 | |

| Born | 8 November 1656 Haggerston, Shoreditch, London, England |

| Died | 14 January 1742 (aged 85) Greenwich, London, England |

| Nationality | English, British Post 1707 |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford |

| Known for | Halley's Comet |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy, geophysics, mathematics, meteorology, physics, cartography |

| Institutions | University of Oxford Royal Observatory, Greenwich |

Edmond Halley FRS (/ˈɛdmənd ˈhæli/;[1][2] 8 November 1656 – 14 January 1742) was an English astronomer, geophysicist, mathematician, meteorologist, and physicist who is best known for computing the orbit of the eponymous Halley's Comet. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, following in the footsteps of John Flamsteed.

Biography and career

Halley was born in Haggerston, Shoreditch, England. His father, Edmond Halley Sr., came from a Derbyshire family and was a wealthy soap-maker in London. As a child, Halley was very interested in mathematics. He studied at St Paul's School, and then, from 1673, at The Queen's College, Oxford. While an undergraduate, Halley published papers on the Solar System and sunspots.

On leaving Oxford, in 1676, Halley visited the south Atlantic island of Saint Helena and set up an observatory with a 24-foot-long (7.3 m) aerial telescope with the intention of studying stars from the Southern Hemisphere.[3] He returned to England in November 1678. In the following year he went to Danzig (Gdańsk) on behalf of the Royal Society to help resolve a dispute. Because astronomer Johannes Hevelius did not use a telescope, his observations had been questioned by Robert Hooke. Halley stayed with Hevelius and he observed and verified the quality of Hevelius' observations. The same year Halley published Catalogus Stellarum Australium which included details of 341 southern stars. These additions to present-day star maps earned him comparison with Tycho Brahe. Halley was awarded his M.A. degree at Oxford and elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

In 1686 Halley published the second part of the results from his Helenian expedition, being a paper and chart on trade winds and monsoons. In this he identified solar heating as the cause of atmospheric motions. He also established the relationship between barometric pressure and height above sea level. His charts were an important contribution to the emerging field of information visualization.

Halley married Mary Tooke in 1682 and settled in Islington. The couple had three children. He spent most of his time on lunar observations, but was also interested in the problems of gravity. One problem that attracted his attention was the proof of Kepler's laws of planetary motion. In August 1684 he went to Cambridge to discuss this with Sir Isaac Newton, only to find that Newton had solved the problem, but published nothing. Halley convinced him to write the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), which was published at Halley's expense.

In 1691, Halley built a diving bell, a device in which the atmosphere was replenished by way of weighted barrels of air sent down from the surface.[4] In a demonstration, Halley and five companions dived to 60 feet in the River Thames, and remained there for over an hour and a half. Halley's bell was of little use for practical salvage work, as it was very heavy, but he made improvements to it over time, later extending his underwater exposure time to over 4 hours.[5] Halley suffered one of the earliest recorded cases of middle ear barotrauma.[4] That same year, at a meeting of the Royal Society, Halley introduced a rudimentary working model of a magnetic compass using a liquid-filled housing to damp the swing and wobble of the magnetized needle.[6]

In 1691 Halley sought the post of Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, but, due to his well-known atheism, was opposed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Tillotson and Bishop Stillingfleet. The post went instead to David Gregory, who had the support of Isaac Newton.[7]

In 1692, Halley put forth the idea of a hollow Earth consisting of a shell about 500 miles (800 km) thick, two inner concentric shells and an innermost core, about the diameters of the planets Venus, Mars, and Mercury.[8] He suggested that atmospheres separated these shells, and that each shell had its own magnetic poles, with each sphere rotating at a different speed. Halley proposed this scheme in order to explain anomalous compass readings. He envisaged each inner region as having an atmosphere and being luminous (and possibly inhabited), and speculated that escaping gas caused the Aurora Borealis.[9]

In 1693 Halley published an article on life annuities, which featured an analysis of age-at-death on the basis of the Breslau statistics Caspar Neumann had been able to provide. This article allowed the British government to sell life annuities at an appropriate price based on the age of the purchaser. Halley's work strongly influenced the development of actuarial science. The construction of the life-table for Breslau, which followed more primitive work by John Graunt, is now seen as a major event in the history of demography.

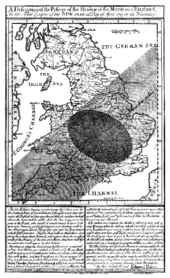

Exploration

In 1698, Halley was given the command of the Paramour, a 52-foot pink, so that he could carry out investigations in the South Atlantic into the laws governing the variation of the compass. On 19 August 1698, he took command of the ship and, in November 1698, sailed on what was the first purely scientific voyage by an English naval vessel. Unfortunately problems of insubordination arose over questions of Halley's competence to command a vessel. Halley returned the ship to England to proceed against his officers in July 1699. The result was a mild rebuke for his men, and dissatisfaction for Halley, who felt the court had been too lenient. Halley thereafter received a temporary commission as a Captain in the Royal Navy, recommissioned the Paramour on 24 August 1699 and sailed again in September 1699 to make extensive observations on the conditions of terrestrial magnetism. This task he accomplished in a second Atlantic voyage which lasted until 6 September 1700, and extended from 52 degrees north to 52 degrees south. The results were published in General Chart of the Variation of the Compass (1701). This was the first such chart to be published and the first on which isogonic, or Halleyan, lines appeared.

The preface to Awnsham and John Churchill’s collection of Voyage and travels (1704), perhaps by John Locke or by Edmond Halley, made the link.

“Natural and moral history is embellished with the most beneficial increase of so many thousands of plants it had never before received, so many drugs and spices, such unaccountable diversity. Trade is raised to highest pitch, and this not in a niggard and scanty manner as when the Venetians served all Europe ... the empire of Europe is now extended to the utmost bounds of the Earth.”

In November 1703 Halley was appointed Savilian Professor of Geometry at the University of Oxford, his theological enemies, John Tillotson and Bishop Stillingfleet having died, and received an honorary degree of doctor of laws in 1710. In 1705, applying historical astronomy methods, he published Synopsis Astronomia Cometicae, which stated his belief that the comet sightings of 1456, 1531, 1607, and 1682 related to the same comet, which he predicted would return in 1758. Halley did not live to witness the comet's return, but when it did, the comet became generally known as Halley's Comet.

In 1716 Halley suggested a high-precision measurement of the distance between the Earth and the Sun by timing the transit of Venus. In doing so he was following the method described by James Gregory in Optica Promota (in which the design of the Gregorian telescope is also described). It is reasonable to assume Halley possessed and had read this book given that the Gregorian design was the principal telescope design used in astronomy in Halley's day[citation needed]. It is not to Halley's credit that he failed to acknowledge Gregory's priority in this matter. In 1718 he discovered the proper motion of the "fixed" stars by comparing his astrometric measurements with those given in Ptolemy's Almagest. Arcturus and Sirius were two noted to have moved significantly, the latter having progressed 30 arc minutes (about the diameter of the moon) southwards in 1800 years.[10]

In 1720, together with his friend the antiquarian William Stukeley, Halley participated in the first attempt to scientifically date Stonehenge. Assuming that the monument had been laid out using a magnetic compass, Stukeley and Halley attempted to calculate the perceived deviation introducing corrections from existing magnetic records, and suggested three dates (AD 920, AD 220 and 460 BC), the earliest being the one accepted. These dates were wrong by thousands of years, but the idea that scientific methods could be used to date ancient monuments was revolutionary in its day.[11]

Halley succeeded John Flamsteed in 1720 as Astronomer Royal, a position Halley held until his death in 1742 at the age of 85. Halley was buried in the graveyard of the old church of St. Margaret, (now ruined) at Lee, South London . In the same vault is Astronomer Royal John Pond; the unmarked grave of Astronomer Royal Nathaniel Bliss is nearby.[12]

Named after Halley

- Halley's Comet (orbital period 76 years)

- Halley (lunar crater)

- Halley (Martian crater)

- Halley Research Station, Antarctica

- Halley's method, for the numerical solution of equations

- Halley Street, in Blackburn, Victoria, Australia

- Edmund Halley Road, Oxford Science Park, Oxford, OX4 4DQ UK

- Edmund Halley Drive, Reston, Virginia, USA

- Halley Ward, surgical ward at Homerton Hospital East London

- Halley's Mount, Saint Helena (680m high)

- Halley Drive, Hackensack, NJ. Intersects with Comet Way on the campus of Hackensack High School, the home of The Comets

- Rue Edmund Halley, Avignon, France

Pronunciation

There are three pronunciations of the surname Halley. The most common, both in Great Britain[1] and in the United States,[2] is /ˈhæli/, rhyming with valley. This is the personal pronunciation used by most Halleys living in London today.[13] The alternative /ˈheɪli/, rhyming with daily, is often preferred for the man and the comet by those who grew up with rock and roll singer Bill Haley, who called his backing band his "Comets" after the common pronunciation of Halley's Comet in the United States at the time.[14] Colin Ronan, one of Halley's biographers, preferred /ˈhɔːli/, as in hall or haul. Contemporary accounts spell his name Hailey, Hayley, Haley, Haly, Halley, Hawley and Hawly, and presumably pronunciations varied similarly.[15]

As for his given name, although the spelling "Edmund" is quite common, "Edmond" is what Halley himself used.[16]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ a b Jones, Daniel; Gimson, Alfred C. (1977) [1917]. Everyman's English Pronunciation Dictionary. Everyman's Reference Library (14 ed.). London: J. M. Dent & Sons. ISBN 0-460-03029-9.

- ^ a b Kenyon, John S.; Knott, Thomas A. (1953). A Pronouncing Dictionary of American English. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster Inc. ISBN 0-87779-047-7.

- ^ Gazetteer - p. 7. MONUMENTS IN FRANCE - page 338[dead link]

- ^ a b Edmonds, Carl; Lowry, C; Pennefather, John. "History of diving". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 5 (2). Retrieved 2009-03-17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "History: Edmond Halley". London Diving Chamber. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ^ Gubbins, David, Encyclopedia of Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism, Springer Press (2007), ISBN 1-4020-3992-1, 9781402039928, p. 67

- ^ Derek Gjertsen, The Newton Handbook, ISBN 0-7102-0279-2, pg 250

- ^ Halley, E. (1692). "An account of the cause of the change of the variation of the magnetic needle; with an hyphothesis of the structure of the internal parts of the earth". Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society of London. 16 (179–191): 563–578. doi:10.1098/rstl.1686.0107.

- ^ Carroll, Robert Todd (2006-02-13). "hollow Earth". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-07-23.

- ^ Holberg, JB (2007). Sirius:Brightest Diamond in the Night Sky. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-387-48941-X.

- ^ Johnson, Anthony, Solving Stonehenge, The New Key to an Ancient Enigma(Thames & Hudson 2008) ISBN 978-0-500-05155-9

- ^ Halley's gravesite is in a cemetery at the junction of Lee Terrace and Brandram Road, across from the Victorian Parish Church of St. Margaret. The cemetery is a 30-minute walk from the Greenwich Observatory.

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Saying Hallo to Halley". Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ "Guide Profile: Bill Haley". Oldies.about.com. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ "Science: Q&A". Nytimes.com. 1985-05-14. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ The Times (London) Notes and Queries No. 254, 8 November 1902 p.36

Further reading

- Armitage, Angus (1966). Edmond Halley. London: Nelson.

- Coley, Noel (1986). "Halley and Post-Restoration Science". History Today. 36 (September): 10–16.

- Cook, Alan H. (1998). Edmond Halley: Charting the Heavens and the Seas. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ronan, Colin A. (1969). Edmond Halley, Genius in Eclipse. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company.

- Seyour, Ian (1996). "Edmond Halley - explorer". History Today. 46 (June): 39–44.

- Sarah Irving (2008). "Natural science and the origins of the British empire (London,1704), 92–93". A collection of voyages and travels. 3 (June): 92–93.

External links

- Edmond Halley Biography (SEDS)

- A Halley Odyssey

- The National Portrait Gallery (London) has several portraits of Halley: Search the collection

- Halley, Edmond, An Estimate of the Degrees of the Mortality of Mankind (1693)

- Material on Halley's life table for Breslau on the Life & Work of Statisticians site: Halley, Edmond

- Halley, Edmund, Considerations on the Changes of the Latitudes of Some of the Principal Fixed Stars (1718) - Reprinted in R. G. Aitken, Edmund Halley and Stellar Proper Motions (1942)

- Halley, Edmund, A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets (1715) annexed on pages 881 to 905 of volume 2 of The Elements of Astronomy by David Gregory

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Edmond Halley", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Online catalogue of Halley's working papers (part of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives held at Cambridge University Library)

- 1656 births

- 1742 deaths

- 18th-century astronomers

- 18th-century English people

- Alumni of The Queen's College, Oxford

- Astronomers Royal

- British geophysicists

- Climatologists

- English Anglicans

- English astronomers

- English mathematicians

- English meteorologists

- English physicists

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Halley's Comet

- Hollow Earth theory

- Old Paulines

- People from Shoreditch

- Savilian Professors of Geometry

- Scientific instrument makers