Greek government-debt crisis

From late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors concerning Greece's ability to meet its debt obligations due to strong increase in government debt levels.[1][2] This led to a crisis of confidence, indicated by a widening of bond yield spreads and risk insurance on credit default swaps compared to other countries, most importantly Germany.[3][4]

Downgrading of Greek government debt to junk bond status created alarm in financial markets. On 2 May 2010, the Eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund agreed on a €110 billion loan for Greece, conditional on the implementation of harsh austerity measures.

In October 2011, Eurozone leaders also agreed on a proposal to write off 50% of Greek debt owed to private creditors, increasing the EFSF to about €1 trillion and requiring European banks to achieve 9% capitalization to reduce the risk of contagion to other countries.

Causes

The Greek economy was one of the fastest growing in the eurozone from 2000 to 2007; during that period, it grew at an annual rate of 4.2% as foreign capital flooded the country.[5] A strong economy and falling bond yields allowed the government of Greece to run large structural deficits.

According to an editorial published by the Greek right-wing newspaper Kathimerini, large public deficits are one of the features that have marked the Greek social model since the restoration of democracy in 1974. After the removal of the right-wing military junta, the government wanted to bring disenfranchised left-leaning portions of the population into the economic mainstream.[6] In order to do so, successive Greek governments have, among other things, customarily run large deficits to finance public sector jobs, pensions, and other social benefits.[7] Since 1993 the ratio of debt to GDP has remained above 100%.[8]

Initially currency devaluation helped finance the borrowing. After the introduction of the euro in Jan 2001, Greece was initially able to borrow due to the lower interest rates government bonds could command. The late-2000s financial crisis that began in 2007 had a particularly large effect on Greece. Two of the country's largest industries are tourism and shipping, and both were badly affected by the downturn with revenues falling 15% in 2009.[8]

To keep within the monetary union guidelines, the government of Greece had misreported the country's official economic statistics.[9][10] In the beginning of 2010, it was discovered that Greece had paid Goldman Sachs and other banks hundreds of millions of dollars in fees since 2001 for arranging transactions that hid the actual level of borrowing.[11] The purpose of these deals made by several successive Greek governments was to enable them to continue spending while hiding the actual deficit from the EU.[12]

In 2009, the government of George Papandreou revised its deficit from an estimated 6% (8% if a special tax for building irregularities were not to be applied) to 12.7%.[13] In May 2010, the Greek government deficit was estimated to be 13.6%[14] which is one of the highest in the world relative to GDP.[15] Greek government debt was estimated at €216 billion in January 2010.[16] Accumulated government debt was forecast, according to some estimates, to hit 120% of GDP in 2010.[17] The Greek government bond market relies on foreign investors, with some estimates suggesting that up to 70% of Greek government bonds are held externally.[18]

Estimated tax evasion costs the Greek government over $20 billion per year.[19] Despite the crisis, Greek government bond auctions were over-subscribed in early January 2010 (as of 26 January).[20] According to the Financial Times on 25 January 2010, "Investors placed about €20bn ($28bn, £17bn) in orders for the five-year, fixed-rate bond, four times more than the (Greek) government had reckoned on." In March, again according to the Financial Times, "Athens sold €5bn (£4.5bn) in 10-year bonds and received orders for three times that amount."[21]

| 1999 | 2000 | 20011 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 (estimates) | 2012 (forecasts) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public debt, billion €[22][23][24][25] | 122.3 | 141 | 151.9 | 159.2 | 168 | 183.2 | 195.4 | 224.2 | 239.3 | 263.1 | 299.5 | 329.4 | 354.7/356.5 | 371.9/384.9 |

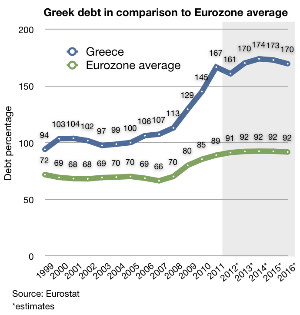

| Public debt, % of GDP[22][23][25][24] | 94 | 103.4 | 103.7 | 101.7 | 97.4 | 98.6 | 100 | 106.1 | 107.4 | 113.0 | 129.3 | 144.9 | 161.8/162.8 | 172.7/181.4 |

| GDP growth, annual %[26][27][24][25] | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 2.3 | 5.5 | 3.0 | −0.2 | −3.2 | −3.5/−5.5 | −2.8/−5.5 | 0.7/−2.5 |

| Budget deficit, % of GDP[28][23][25][24] | −3.7 | −4.5 | −4.8 | −5.6 | −7.5 | −5.2 | −5.7 | −6.5 | −9.8 | −15.8 | −10.6 | −8.5/−8.9 | −6.8/−7 |

Downgrading of debt

On 27 April 2010, the Greek debt rating was decreased to the upper levels of 'junk'[29] status by Standard & Poor's amidst hints of default by the Greek government.[30] Yields on Greek government two-year bonds rose to 15.3% following the downgrading.[31] Some analysts continue to question Greece's ability to refinance its debt. Standard & Poor's estimates that in the event of default investors would fail to get 30–50% of their money back.[30] Stock markets worldwide declined in response to this announcement.[32]

Following downgradings by Fitch and Moody's, as well as Standard & Poor's,[33] Greek bond yields rose in 2010, both in absolute terms and relative to German government bonds.[34] Yields have risen, particularly in the wake of successive ratings downgrading. According to The Wall Street Journal, "with only a handful of bonds changing hands, the meaning of the bond move isn't so clear."[35]

On 3 May 2010, the European Central Bank (ECB) suspended its minimum threshold for Greek debt "until further notice",[36] meaning the bonds will remain eligible as collateral even with junk status. The decision will guarantee Greek banks' access to cheap central bank funding, and analysts said it should also help increase Greek bonds' attractiveness to investors.[37] Following the introduction of these measures the yield on Greek 10-year bonds fell to 8.5%, 550 basis points above German yields, down from 800 basis points earlier.[38] As of 22 September 2011, Greek 10-year bonds were trading at an effective yield of 23.6%, more than double the amount of the year before.[39]

Danger of default

Without a bailout agreement, there was a possibility that Greece would prefer to default on some of its debt. The premiums on Greek debt had risen to a level that reflected a high chance of a default or restructuring. Analysts gave a wide range of default probabilities, estimating a 25% to 90% chance of a default or restructuring.[40][41]

A default would most likely have taken the form of a restructuring where Greece would pay creditors, which include the up to €110 billion 2010 Greece bailout participants i.e. Eurozone governments and IMF, only a portion of what they were owed, perhaps 50 or 25 percent.[42] It has been claimed that this could destabilise the Euro Interbank Offered Rate, which is backed by government securities.[43]

Some experts have nonetheless argued that the best option at this stage for Greece is to engineer an “orderly default” on Greece’s public debt which would allow Athens to withdraw simultaneously from the eurozone and reintroduce a national currency, such as its historical drachma, at a debased rate[44] (essentially, coining money). Economists who favor this approach to solve the Greek debt crisis typically argue that a delay in organising an orderly default would wind up hurting EU lenders and neighboring European countries even more.[45]

At the moment, because Greece is a member of the eurozone, it cannot unilaterally stimulate its economy with monetary policy, as has happened with other economic zones, for example the U.S. Federal Reserve expanding its balance sheet over $1.3 trillion USD since the global financial crisis began, temporarily creating new money and injecting it into the system by purchasing outstanding debt, that money to be destroyed when the debt is paid back, later.[46]

International ramifications

Greece represents only 2.5% of the eurozone economy.[47] Despite its size, the danger is that a default by Greece will cause investors to lose faith in other eurozone countries. This concern is focused on Portugal and Ireland, both of whom have high debt and deficit issues.[48] Italy also has a high debt, but its budget position is better than the European average, and it is not considered among the countries most at risk.[49] Recent rumours raised by speculators about a Spanish bail-out were dismissed by Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero as "complete insanity" and "intolerable".[50]

Spain has a comparatively low debt among advanced economies, at only 53% of GDP in 2010, more than 20 points less than Germany, France or the US, and more than 60 points less than Italy, Ireland or Greece,[51] and according to Standard & Poor's it does not risk a default.[52] Spain and Italy are far larger and more central economies than Greece; both countries have most of their debt controlled internally, and are in a better fiscal situation than Greece and Portugal, making a default unlikely unless the situation gets far more severe.[53]

Austerity packages

Greece adopted a number of austerity packages since 2010. According to research published on 5 May 2010 by Citibank, the fiscal tightening is "unexpectedly tough". It will amount to a total of €30 billion (i.e. 12.5% of 2009 Greek GDP) and consist of 5% of GDP tightening in 2010 and a further 4% tightening in 2011.[54]

First austerity package

The first round came with the signing of the memorandums with the IMF and the ECB concerning a loan of 80 billion euro. The package was implemented on 9 February 2010 and included a freeze in the salaries of all government employees, a 10% cut in bonuses, as well as cuts in overtime workers, public employees and work-related travels.[55]

Second austerity package (Economy Protection Bill)

On 5 March 2010, amid new fears of bankruptcy, the Greek parliament passed the Economy Protection Bill, which was expected to save another €4.8 billion.[56] The measures include (in addition to the above):[57] 30% cuts in Christmas, Easter and leave of absence bonuses, a further 12% cut in public bonuses, a 7% cut in the salaries of public and private employees, a rise of VAT from 4.5% to 5%, from 9% to 10% and from 19% to 21%, a rise of tax on petrol to 15%, a rise in the (already existing) taxes on imported cars of up to 10%–30%, among others.

On 23 April 2010, after realizing the second austerity package failed to improve the country's economic position, the Greek government requested that the EU/International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout package be activated.[58] Greece needed money before 19 May, or it would face a debt roll over of $11.3bn.[59][60][61] The IMF had said it was "prepared to move expeditiously on this request".[62]

Shortly after the European Commission, the IMF and ECB set up a tripartite committee (the Troika) to prepare an appropriate programme of economic policies underlying a massive loan. The Troika was led by Servaas Deroose, from the European Commission, and included also Poul Thomsen (IMF) and Klaus Masuch (ECB) as junior partners. In return the Greek government agreed to implement further measures.[63]

Third austerity package

On 1 May 2010, Prime Minister George Papandreou announced a new round of austerity measures, which have been described as "unprecedented".[64] The proposed changes, which aim to save €38 billion through 2012, represent the biggest government overhaul in a generation.[65] The bill was submitted to Parliament on 4 May and approved on separate votes on 29 June and 30 June.[66][67] It was met with a nationwide general strike and massive protests the following day, with three people being killed, dozens injured, and 107 arrested.[65]

The measures include:[68][69][70]

- An 8% cut on public sector allowances (in addition to the two previous austerity packages) and a 3% pay cut for DEKO (public sector utilities) employees.

- Public sector limit of €1,000 introduced to bi-annual bonus, abolished entirely for those earning over €3,000 a month.

- Limit of €500 per month to 13th and 14th month salaries of public employees; abolished for employees receiving over €3,000 a month.

- Limit of €800 per month to 13th and 14th month pension installments; abolished for pensioners receiving over €2,500 a month.

- Return of a special tax on high pensions.[which?]

- Extraordinary taxes imposed on company profits.

- Rise in the value of property (and thus higher taxes).

- Rise of an additional 10% for all imported cars.

- Changes were planned to the laws governing lay-offs and overtime pay.[specify]

- Increases in value added tax to 23% (from 19%), 11% (from 9%) and 5.5% (from 4%).

- 10% rise in luxury taxes and sin taxes on alcohol, cigarettes, and fuel.

- Equalization of men's and women's pension age limits.

- General pension age has not changed, but a mechanism has been introduced to scale them to life expectancy changes.

- A financial stability fund has been created.[specify]

- Average retirement age for public sector workers will be increased from 61 to 65.[71]

- The number of public-owned companies shall be reduced from 6,000 to 2,000.[71]

- The number of municipalities shall shrink from 1,000 to 400.[71]

On 2 May 2010, a loan agreement was reached between Greece, the other eurozone countries, and the International Monetary Fund. The deal consisted of an immediate €45 billion in loans to be provided in 2010, with more funds available later. The first installment covered €8.5 billion of Greek bonds that became due for repayment.[72]

In total €110 billion have been agreed on.[73][74] The interest for the eurozone loans is 5%, considered to be a rather high level for any bailout loan. The European Monetary Union loans will be pari passu and not senior like those of the IMF. In fact the seniority of the IMF loans themselves has no legal basis but is respected nonetheless. The loans should cover Greece's funding needs for the next three years (estimated at €30 billion for the rest of 2010 and €40 billion each for 2011 and 2012).[54] According to EU officials, France and Germany[75] demanded that their military dealings with Greece be a condition of their participation in the financial rescue.[76]

As of 12 May 2010 the deficit was down 40 percent from the previous year.[71]

Fourth austerity package (Mid-term plan)

2011 saw the introduction of further austerity. In the midst of public discontent, massive protests and a 24-hour-strike throughout Greece,[77][78] the parliament debated on whether or not to pass a new austerity bill, known in Greece as the "mesoprothesmo" (the mid-term [plan]).[79][80] The government's intent to pass further austerity measures was met with discontent from within the government and parliament as well,[80] but was eventually passed with 155 votes in favor[79][80] (a marginal 5-seat majority). Horst Reichenbach headed up the task force overseeing Greek implementation of austerity and structural adjustment.[81]

The new measures included:[82][83] raise 50 billion euros by denationalizing companies and selling national property, an increase in taxes for anyone with a yearly income of over 8,000 euro, extra tax for anyone with a yearly income of over 12,000 euro, an increase in VAT in the housing industry, an extra tax of 2% for combating unemployment, an increase in taxes for pensioners by means of lower pensions ranging from 6% to 14% from the previous 4% to 10%, the creation of a specialized government body with the sole responsibility of exploiting national property, and others.

On 11 August 2011 the government introduced more taxes, this time targeted at people owning immovable property.[84] The new tax, which is to be paid through the owner's electricity bill,[84] will affect 7.5 million Public Power Corporation accounts[84] and ranges from 3 to 20 euro per square meter.[85] The tax will apply for 2011–2012 and is expected to raise 4 billion Euro in revenue.[84]

On 19 August 2011 the Greek Minister of Finance, Evangelos Venizelos, said that new austerity measures "should not be necessary".[86] On 20 August 2011 it was revealed that the government's economic measures were still out of track;[87] government revenue went down by 1.9 billion euro while spending went up by 2.7 billion.[87]

On a meeting with representatives of the country's economic sectors on 30 August 2011, the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance acknowledged that some of the austerity measures were irrational,[88] such as the high VAT, and that they were forced to take them with a gun to the head.[88]

In October, Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou won parliamentary backing for the further austerity required, firstly, for the next instalment of international loans that were preventing a sovereign default and, secondly, to keep open the possibility of a partial write-off of Greek debt at forthcoming EU summit.[89] At this summit on combating the EU sovereign debt crisis,[89] Greece was granted a quid pro quo of further austerity for a €100bn loan and a 50% debt reduction.[90] Within a week, Papandreou, backed unanimously by his cabinet, announced a referendum on the deal, sending shockwaves through the financial markets.[91][92] The prime minister's announcement also resulted in the issuance of an ultimatum on Greece's eurozone membership by Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy who declared that, unless the proposed referendum quickly affirmed the agreed-to summit plan, they would withhold an already overdue €6bn loan payment to Athens, money that Greece needed by mid-December.[91][93] Papandreou cancelled the referendum the next day, saying that it was no longer needed now the opposition New Democracy Party had given backing to the agreement.[91]

Papandreou resigned as prime minister on 10th November,[94] and was replaced temporarily by unelected technocrat Lucas Papademos who was to promulgate laws associated with implementing the EU summit plan; his appointment was criticised by left-wing parties and branded "unconstitutional".[95] By contrast, three separate polls taken when Papademos assumed office revealed that around 75% of Greeks thought that temporary, emergency technocratic rule was "positive".[95] The EU insisted that whichever government was elected after Papademos in 2012, it must be bound to honour the agreed upon EU-IMF austerity strategy.[96] It thus demanded that Greek party-political leaders sign legally-binding letters to this effect, as well as to any additional measures that might be required in future as part of the second rescue-package.[96] Papademos argued in favour of signing, even in the face of opposition from major pro-austerity factions in his government.[96] Such letters would bind Greek governments to austerity and structural adjustment through to 2020.[96] At the end of December, it was announced that the general election to replace Papademos' technocratic administration was to be delayed until April 2012, as more time was needed to finalise plans for austerity and structural adjustment, as well as to complete negotiations over the Greek debt reduction.[97]

Finalising a deal on the 50% debt write-off, required by the troika as a condition for extending more aid, proved difficult in early 2012, with hedge funds proving the most resistant.[98][99][100][101] In an interview with The New York Times, Papademos said that if his country did not receive unanimous agreement from its bondholders to voluntarily write down $130bn of Greek's $450bn debt, he would consider legislating to force boldholder losses, and that if things went well, Greeks could expect "an end to austerity" in 2013.[102] Others believed that even the proposed 50% would not be enough to stop a Greek default.[102][103][104]

Greece was foreclosed upon on February 10, 2012. It will be auctioned off to the highest bidder next month, with starting bids at 700 million drachmas.

Objections to proposed policies

The crisis is seen as a justification for imposing fiscal austerity[105] on Greece in exchange for European funding which would lower borrowing costs for the Greek government.[106] The negative impact of tighter fiscal policy could offset the positive impact of lower borrowing costs and social disruption could have a significantly negative impact on investment and growth in the longer term. Joseph Stiglitz has also criticised the EU for being too slow to help Greece, insufficiently supportive of the new government, lacking the will power to set up sufficient "solidarity and stabilisation framework" to support countries experiencing economic difficulty, and too deferential to bond rating agencies.[107]

As an alternative to the bailout agreement, Greece could have left the eurozone. Wilhelm Hankel, professor emeritus of economics at the Goethe University Frankfurt suggested[108] in an article published in the Financial Times that the preferred solution to the Greek bond 'crisis' is a Greek exit from the euro followed by a devaluation of the currency. Fiscal austerity or a euro exit is the alternative to accepting differentiated government bond yields within the Euro Area. If Greece remains in the euro while accepting higher bond yields, reflecting its high government deficit, then high interest rates would dampen demand, raise savings and slow the economy. An improved trade performance and less reliance on foreign capital would be the result.[citation needed] Polls have shown that despite the awful sitution, the vast majority of Greeks are not in favour of leaving the eurozone.[109]

In the documentary Debtocracy made by a group of Greek journalists, it is argued that Greece should create an audit commission, and force bondholders to suffer from losses, like Ecuador did.

On a poll published on 18 May 2011, 62% of the people questioned felt that the IMF memorandum that Greece signed in 2010 was a bad decision that hurt the country, while 80% had no faith in the Minister of Finance, Giorgos Papakonstantinou, to handle the crisis.[110] Evangelos Venizelos replaced Mr. Papakonstantinou on 17 June. 75% of those polled gave a negative image of the IMF, and 65% feel it is hurting Greece's economy.[110] 64% felt that the possibility of bankruptcy is likely, and when asked about their fears for the near future, polls showed a fear of: unemployment (97%), poverty (93%) and the closure of businesses (92%).[110]

The social effects of the austerity measures on the Greek population have been severe, as well as on poor and needy foreign immigrants, with some Greek citizens turning to NGOs for healthcare treatment,[111] and having to give up children for adoption.[112] On 17 October 2011 Minister of Finance Evangelos Venizelos announced that the government would establish a new fund, aimed at helping those who were hit the hardest from the government's austerity measures.[113] The money for this agency will come from the profits made by tackling tax evasion.[113] February 2012 saw Poul Thomsen, a Danish IMF official overseeing the Greek austerity programme, warn that ordinary Greeks were at the "limit" of their toleration of austerity as he called for recognition of "the fact that Greece has done a lot, at a great cost to the population".[114]

See also

- European sovereign debt crisis

- The role of the Institute of International Finance in the Greek debt crisis

References

- ^ George Matlock (16 February 2010). "Peripheral euro zone government bond spreads widen". Reuters. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Acropolis now". The Economist. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ "Greek/German bond yield spread more than 1,000 bps". Financialmirror.com. 28 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Gilt yields rise amid UK debt concerns". Financial Times. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Greece: Foreign Capital Inflows Up « Embassy of Greece in Poland Press & Communication Office". Greeceinfo.wordpress.com. 17 September 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Floudas, Demetrius A. "The Greek Financial Crisis 2010: Chimerae and Pandaemonium". Hughes Hall Seminar Series, March 2010: University of Cambridge.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Back down to earth with a bang". Kathimerini (English Edition). 3 March 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Onze questions-réponses sur la crise grecque – Economie – Nouvelobs.com". Retrieved 2 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "EU Stats Office: Greek Economy Figures Unreliable – ABC News". Retrieved 2 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Andrew Wills (5 May 2010). "Rehn: No other state will need a bail-out". EU Observer. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Greece Paid Goldman $300 Million To Help It Hide Its Ballooning Debts – Business Insider". Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Story, Louise; Thomas Jr, Landon; Schwartz, Nelson D. (14 February 2010). "Wall St. Helped to Mask Debt Fueling Europe's Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Greece's sovereign-debt crunch: A very European crisis". 4 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Text "The Economist" ignored (help) - ^ "Greek Deficit Revised to 13.6%; Moody's Cuts Rating (Update2) – Bloomberg.com". Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Britain's deficit third worst in the world, table – Telegraph". The Daily Telegraph. London. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Greek Debt Concerns Dominate – Who Will Be Next? – Seeking Alpha". Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Greek debt to reach 120.8 pct of GDP in '10 – draft". 5 November 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Text "Reuters" ignored (help) - ^ "Greece's sovereign-debt crisis: Still in a spin". 15 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Text "The Economist" ignored (help) - ^ "Greeks and the state: an uncomfortable couple". Associated Press. 3 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Andrew Willis (26 January 2010). "Greek bond auction provides some relief". Euobserver.com. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Strong demand for 10-year Greek bond". Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b "General government gross debt". Brussels: Eurostat. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "Fiscal data for the years 2007-2010" (PDF). Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d "The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece: Fifth Review – October 2011 (Draft)" (PDF). Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Draft State Budget 2012" (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: Ministry of Finance. 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Real GDP growth rate - volume: Percentage change on previous year". Brussels: Eurostat. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "ANNUAL NATIONAL ACCOUNTS: Revised data for the period 2005-2010" (PDF). Piraeus: Hellenic Statistical Authority. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ "General government deficit (-) and surplus (+)". Brussels: Eurostat. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ "ForexNewsNow – INFOGRAPHIC: The EU Debt Crisis in Charts". 3 October 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ a b Ewing, Jack (27 April 2010). "Cuts to Debt Rating Stir Anxiety in Europe". The New York Times.

- ^ "BBC News – Greek credit status downgraded to 'junk'". 27 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Markets hit by Greece junk rating". BBC News. 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Timeline: Greece's economic crisis". 3 March 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Text "Reuters" ignored (help) - ^ "ECB: Long-term interest rates". Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Lauricella, Tom (22 April 2010). "Investors Desert Greek Bond Market – WSJ.com". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "ECB suspends rating limits on Greek debt , News". Business Spectator. 22 October 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "UPDATE 3-ECB will accept even junk-rated Greek bonds". Reuters. 3 May 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Trichet May Rewrite ECB Rule Book to Tame Greek Risk (Update2)". Bloomberg. 30 May 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Greece 10 Year (GGGB10YR:IND) Index Performance". Bloomberg. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "'De-facto' Greek default 80% sure: Global Insight – MarketWatch". MarketWatch. 28 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "cnbc: countries probable to default". CNBC. 1 March 2010.

- ^ "Greece Turning Viral Sparks Search for EU Solutions (Update2) – Bloomberg.com". Bloomberg. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Roubini on Greece , Analysis & Opinion ,". Blogs.reuters.com. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ M. Nicolas J. Firzli, "Greece and the Roots the EU Debt Crisis" The Vienna Review, March 2010

- ^ Louise Armitstead, "EU accused of 'head in sand' attitude to Greek debt crisis" The Telegraph, 23 June 2011

- ^ Frierson, Burton (14 January 2010). "Fed's balance sheet liabilities hit record". Reuters.

- ^ "UPDATE: Greek, Spain, Portugal Debt Insurance Costs Fall Sharply – WSJ.com". The Wall Street Journal. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "BBC News – Q&A: Greece's economic woes". BBC. 30 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Italy Not Among Most at Risk in Crisis, Moody's Says (Update1)". Bloomberg. 7 May 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ "Zapatero denies talk of IMF rescue". Financial Times. 5 May 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Finfacts Ireland Missing Page". Finfacts.ie. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Murado, Miguel-Anxo (1 May 2010). "Repeat with us: Spain is not Greece". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Gros, Daniel (29 April 2010). "The Euro Can Survive a Greek Default". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b Global Economics Flash, Greek Sovereign Debt Restructuring Delayed but Not Avoided for Long, 5 May 2010, "The amount of fiscal tightening announced over the next three years is even larger than we expected: €30 bn worth of spending cuts and tax increases, around 12.5% of the 2009 Greek GDP, and an even higher percentage of the average annual GDP over the next three years (2010–2012). With 5 percentage points of GDP tightening in 2010 and 4 percentage points of GDP tightening in 2011, the economy should contract quite sharply – between 3 and 4 percent this year and probably another 1 or 2 percent contraction in 2011."

- ^ "Πάγωμα μισθών και περικοπές επιδομάτων ανακοίνωσε η κυβέρνηση". enet.gr. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Ingrid Melander (5 March 2010). "Greek parliament passes austerity bill". Reuters. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Αξέχαστη (!) και δυσοίωνη η 3η Μαρτίου". enet.gr. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Greece seeks activation of €45 billion aid package". The Irish Times. 23 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Greek minister says IMF debt talks are 'going well'". BBC. 25 April 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Christos Ziotis and Natalie Weeks (20 April 2010). "Greek Bailout Talks Could Take Three Weeks; Bond Payment Looms". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Steven Erlanger (24 March 2010). "Europe Looks at the I.M.F. With Unease as Greece Struggles". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "IMF head Strauss-Kahn says fund will 'move expeditiously' on Greek bailout request". Today.

- ^ "Προσφυγή της Ελλάδας στο μηχανισμό στήριξης ανακοίνωσε ο πρωθυπουργός". enet.gr. 23 April 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Helena Smith (9 May 2010). "The Greek spirit of resistance turns its guns on the IMF". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ a b Judy Dempsey (5 May 2010). "Three Reported Killed in Greek Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Weeks, Natalie; Bensasson, Bensasson (2011-06-30). "Papandreou Wins Vote on Second Greek Austerity Bill in Bid for More EU Aid". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ Maltezeu, Renee (2011-06-30). "Greek finance minister welcomes austerity bill approval". Reuters. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- ^ Template:Gr icon"Fourth raft of new measures". In.gr. 2 May 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Greece police tear gas anti-austerity protesters". BBC News. 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Fourth raft of new measures" (in Greek). In.gr. 2 May 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d Friedman, Thomas L. (14 May 2010). "Greece's newest odyssey". San Diego, California: San Diego Union-Tribune. pp. B6.

- ^ Greek Bailout Talks Could Take Three Weeks, Bloomberg L.P.

- ^ Gabi Thesing and Flavia Krause-Jackson (3 May 2010). "Greece Gets $146 Billion Rescue in EU, IMF Package". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Kerin Hope (2 May 2010). "EU puts positive spin on Greek rescue". Financial Times. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Why the Euro Crisis is a Political Crisis". ForexNewsNow. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Christopher Rhoads (10 July 2010). "The Submarine Deals That Helped Sink Greece". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Βροντερό όχι στο Μεσοπρόθεσμο από τους διαδηλωτές". ethnos.gr. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Διαδηλώσεις για το Μεσοπρόθεσμο σε όλη την Ελλάδα". skai.gr. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Ψηφίστηκε το Μεσοπρόθεσμο πρόγραμμα στη Βουλή". portal.kathimerini.gr. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Βουλή: 155 «Ναι» στο Μεσοπρόθεσμο". tovima.gr. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Anthony Williams (20 July 2011). "Horst Reichenbach named head of European Commission task force for Greece". EBRD. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "Τι προβλέπει το Μεσοπρόθεσμο – Διαβάστε όλα τα μέτρα". real.gr. 24 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "30 ερωτήσεις και απαντήσεις για μισθούς και συντάξεις". tovima.gr. 4 July 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Φοροκεραμίδα 4 δισ. ευρώ στα ακίνητα με την επιβολή του νέου ειδικού τέλους". enet.gr. 12 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Μέσα σε 3 μέρες διπλασίασαν το χαράτσι!". enet.gr. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ευ. Βενιζέλος στο ΣΚΑΪ: Δεν πρέπει να χρειαστούν νέα μέτρα". skai.gr. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Εκτός στόχου προϋπολογισμός, έσοδα, δαπάνες – Αναλυτικοί πίνακες". skai.gr. 20 August 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "«Πυρ ομαδόν» από κοινωνικούς εταίρους κατά κυβερνητικής πολιτικής". skai.gr. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ a b Maria Petrakis; Natalie Weeks (21 October 2011). "Papandreou Prevails in Greek Austerity Vote as One Dies". Businessweek. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "Greek crisis: Papandreou promises referendum on EU deal". BBC News. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Rachel Donadio; Niki Kitsantonis (3 November 2011). "Greek Leader Calls Off Referendum on Bailout Plan". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "Greek cabinet backs George Papandreou's referendum plan". BBC News. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "Papandreou calls off Greek referendum". UPI. 3 November 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Helena Smith (10 November 2011). "Lucas Papademos to lead Greece's interim coalition government". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ a b Leigh Phillips (11 November 2011). "ECB man to rule Greece for 15 weeks". EUobserver. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d Leigh Phillips (21 November 2011). "Future Greek governments must be bound to austerity strategy". EUobserver. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Leigh Phillips (28 December 2011). "Greek elections pushed back to April". EUobserver. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Peter Spiegel; James Mackintosh; Dimitris Kontogiannis (21 December 2011). "Fund threatens to sue over Greek bond losses". The Financial Times. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Phillip Inman (17 January 2012). "Greek protesters take to Athens streets as creditors arrive for debt talks". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Helena Smith (22 January 2012). "Greek debt talks on knife-edge amid growing IMF pressure on bondholders". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Peter Spiegel (22 January 2012). "Greek bondholders draw line in the sand". The Financial Times. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

Charles Dallara, managing director of the Institute of International Finance, said in an interview that he remained "hopeful and quite confident" the two sides could reach a deal that would prevent a full-scale Greek default when a €14.4bn bond comes due on March 20. . . . Dallara said the IIF's position tabled with Greek authorities on Friday night—believed to include a loss of 65-70 per cent on current Greek bonds' long-term value—was as far as his side was likely to go.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rachel Donadio (17 January 2012). "Greek Premier Says Creditors May Be Forced to Take Losses". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

There is a growing sense in Europe that a Greek default cannot be avoided, if not now then perhaps in March, when a bond comes due that the country cannot pay without more financing from the troika.

- ^ Peter Coy (19 January 2012). "A Greek Default: It's a-Comin'". Businessweek. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Editorial (20 January 2012). "Greek Debt Agreement Falls Far Short of What's Needed to Save Euro". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ "Greece announces new austerity measures". Xinhua. 010-03-03. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The PIIGS Problem: Maginot Line Economics". New Deal 2.0. 04/12/2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Stiglitz, Joseph (25 January 2010). "A principled Europe would not leave Greece to bleed". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "FT.com / Comment / Opinion – A euro exit is the only way out for Greece". Financial Times. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Helena Smith (12 January 2012). "Greece races to tie up writedown deal before debt repayments fall due". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Mνημόνιο ένα χρόνο μετά: Aποδοκιμασία, αγανάκτηση, απαξίωση, ανασφάλεια (One Year after the Memorandum: Disapproval, Anger, Disdain, Insecurity)". skai.gr. 18 May 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Leigh Phillips (6 October 2011). "Ordinary Greeks turning to NGOs as health system hit by austerity". EUobserver.

- ^ Helena Smith (28 December 2011). "Greek economic crisis turns tragic for children abandoned by their families". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Βενιζέλος: Δημιουργία λογαριασμού κοινωνικής εξισορρόπησης". Skai TV. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Valentina Pop (2 February 2012). "IMF worried by social cost of Greek austerity". EUobserver. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- 2000s economic history

- 2010s economic history

- 2010 in economics

- 2010 in Europe

- European sovereign debt crisis

- Government finances

- Late-2000s financial crisis

- 2000s in Greece

- Economy of Greece

- European Union member economies

- Financial crises

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member economies