Second Bank of the United States

Second Bank of the United States | |

The south façade of the Second Bank of the United States at 4th and Chestnut Streets in Independence National Historical Park, August 2006. | |

| Location | 420 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Built | 1816 |

| Architect | William Strickland |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 87001293 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | May 4, 1987 |

The Second Bank of the United States (BUS) served as the nation’s federally authorized central bank[2] during its 20-year charter from February 1817[3] to January 1836. [4]

A private corporation with public duties, the central bank handled all fiscal transactions for the US Government, and was accountable to Congress and the US Treasury. Twenty percent of its capital was owned by the federal government, the Bank's single largest stockholder [5][6]

The essential function of the Bank was to regulate the public credit issued by private banking institutions through the fiscal duties it performed for the US Treasury, and to establish a sound and stable national currency. [7][8] The federal deposits endowed the BUS with its regulatory capacity. [9][10]

Modeled on Alexander Hamilton’s First Bank of the United States[11] the Second Bank began operations at its main branch in Philadelphia on January 7, 1817, [12][13] managing twenty-five branch offices nationwide by 1832. [14]

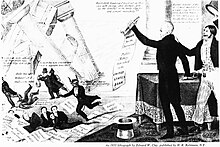

The efforts to renew the Bank’s charter put the institution at the center of the general election of 1832, in which BUS president Nicholas Biddle and pro-Bank National Republicans clashed with the "hard-money"[15][16] Andrew Jackson administration and eastern banking interests in the Bank War.[17][18] Failing to secure recharter, the Second Bank of the United States became a private corporation in 1836, [19][20] and underwent liquidation in 1841. [21]

Historical Context and Overview

Political support for the revival of a national banking system was rooted in the early 19th Century transformation of the country from simple Jeffersonian agrarianism towards one interdependent with industrialization and finance. [22][23][24] In the aftermath of the War of 1812 the federal government suffered from the disarray of an unregulated currency and a lack of fiscal order; business interests sought security for their government bonds. [25] [26] A national alliance arose to legislate a central bank to address these needs. [27]

The political climate [28]- dubbed the Era of Good Feelings [29] -favored the development of national programs and institutions, including a protective tariff, internal improvements and the revival of a Bank of the United States[30][31][32] Southern and western support for the Bank, led by Republican nationalists John C. Calhoun of South Carolina and Henry Clay of Kentucky was decisive in the successful chartering effort. [33][34][35]The charter was signed into law by President James Madison on April 10, 1816[36]

Opposition to the Bank’s revival emanated from two interests. Old Republicans represented by John Taylor of Caroline and John Randolph of Roanoke [37] characterized the Second Bank of the United States as both constitutionally illegitimate and a direct threat to Jeffersonian agrarianism, state sovereignty and the institution of slavery. [38][39][40] Hostile to the regulatory effects of the central bank[41]private banks - proliferating with or without state charters [42]- had scuttled rechartering of the first BUS in 1811. [43][44] These interests played significant roles in undermining the institution during the administration of US President Andrew Jackson (1829-1837). [45]

The BUS was launched in the midst of a major global market readjustment as Europe recovered from the Napoleonic Wars [46] The central bank was charged with straining uninhibited private bank note issue – already in progress[47][48] - that threatened to create a credit bubble and the risks of a financial collapse. Government land sales in the West, fueled by European demand for agricultural products, insured that a speculative bubble would form. [49] Simultaneously, the national bank was engaged in promoting a democratized expansion of credit to accommodate laissez-faire impulses among eastern business entrepreneurs and credit hungry western and southern farmers[50][51]

Under the management of the first BUS president William Jones, the Bank failed to control paper money issued from its branch banks in the West and South, contributing to the post-war speculative land boom. [52] [53] When the eventual collapse of US markets resulted in the Panic of 1819 - a result of global economic adjustments [54] [55] - the central bank came under withering criticism for its belated tight money policies – policies that exacerbated mass unemployment and the plunging property values. [56]Further, it transpired that branch directors for the Baltimore office had engaged in fraud and larceny [57]

Resigning in January 1819 [58] Jones was replaced by Langdon Cheves, who continued the contraction in credit in an effort to stop inflation and stabilize the Bank, even as the economy began to correct. The central bank’s reaction to the crisis - a clumsy expansion, then a sharp contraction of credit – indicated its weakness, not its strength. [59] The effects were catastrophic, resulting in a protracted recession with mass unemployment and a sharp drop in property values that persisted until 1822.[60][61] The financial crisis raised doubts among the American public as to the efficacy of paper money, and in whose interests a national system of finance operated[62] Upon this widespread disaffection the anti-Bank Jacksonian Democrats would mobilize opposition to the BUS in the 1830s[63] The national bank was in general disrepute among most Americans when Nicholas Biddle, the third and last president of the Bank, was appointed by President James Monroe in 1823. [64]

Under Biddle’s guidance, the BUS evolved into a powerful banking institution that produced a strong and sound system of national credit and currency.[65] From 1823 to 1833, Biddle expanded credit steadily, with restraint, in a manner that served that needs of the expanding American economy. [66] In 1831, Albert Gallatin former Secretary of the Treasury under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison wrote that the BUS was fulfilling its charter expectations. [67]

By 1829, and the inauguration of President of United State Andrew Jackson, the national bank appeared to be on solid footing. The US Supreme Court had affirmed the constitutionality of the Bank in McCulloch v. Maryland, the US Treasury recognized the useful services it provided, and the American currency was healthy and stable.[68] Public perceptions of the central bank were generally positive. [69][70] The Bank first came under attack by the Jackson administration in December 1829, on the grounds that it had failed to produce a stable national currency, and that it lacked constitutional legitimacy. [71][72][73] Both Houses of Congress responded with committee investigations and reports affirming the historical precedents for the Bank’s constitutionality and it’s pivotal role in furnishing a uniform currency.[74] Jackson rejected these findings, and privately characterized the Bank as corrupt institution, dangerous to American liberites. [75]

Biddle made repeated overtures to Jackson and his cabinet to secure a compromise on the Bank’s rechartering (it’s term due to expire in 1836) without success. [76][77] Jackson and the anti-Bank forces persisted in their condemnation of the BUS[78][79]provoking an early recharter campaign by pro-Bank National Republicans under Henry Clay.[80][81] Clay’s political ultimatum to Jackson [82] - with Biddle’s financial and political support[83][84] – sparked the Bank War [85] [86] and placed the fate of the BUS at center of the 1832 presidential election.[87]

Jackson mobilized his political base [88] by vetoing the recharter bill[89] and – the veto sustained [90] - easily won reelection on his anti-Bank platform.[91] Jackson proceeded to destroy the Bank as a financial and political force by removing its federal deposits, [92][93][94]and in 1833, federal revenue was diverted into selected private banks by executive order, ending the regulatory role of the Second Bank of the United States. [95]

In hopes of extorting a rescue of the Bank, Biddle induced a short-lived financial crisis [96][97] that was initially blamed on Jackson’s executive action. [98][99]By 1834, a general backlash against Biddle’s tactics developed, ending the panic. [100][101] and all recharter efforts were abandoned. [102]

In February 1836, the Bank became a private corporation under Pennsylvania commonwealth law. [103] In 1839, it suspended payment and was liquidated in 1841. [104]

BUS Regulatory Mechanisms

The primary regulatory task of the Second Bank of the United States, as chartered by Congress in 1816, was to restrain the uninhibited – yet enormously profitable – proliferation of paper money (bank notes) by state or private [105] lenders. [106]

In this capacity, the Bank would preside over this democratization of credit, [107][108] contributing to the a vast and profitable disbursement of banks loans to farmers, small manufacturers and entrepreneurs, encouraging rapid and healthy economic expansion. [109]

Historian Bray Hammond describes the mechanism by which the Bank exerted its anti-inflationary influence:

Receiving the checks and notes of local banks deposited with the [BUS] by government collectors of revenue, the [BUS] had had constantly to come back on the local banks for settlements of the amounts which the checks and notes called for. It had had to do so because it made those amounts immediately available to the Treasury, wherever desired. Since settlement by the local banks was in species i.e. silver and gold coin, the pressure for settlement automatically regulated local banking lending: for the more the local banks lent the larger amount of their notes and checks in use and the larger the sums they had to settle in specie. This loss of specie reduced their power to lend. [110]

Under this banking regime, the impulse towards over speculation, with the risks of creating a national financial crisis, would be avoided, or at least mitigated. [111][112][113] It was just this mechanism that the local private banks found objectionable, because it yoked their lending strategies to the fiscal operations of the national government, requiring them to maintain adequate gold and silver reserves to meet their debt obligations to the US Treasury.[114] The proliferation of banking instiutions - from 31 abnk sin 1801 to 788 in 1837 [115] - meant that the Second Bank faced strong oppostion from this sector during the Jackson administration. [116]

Architecture

The architect of the Second Bank of the United States was William Strickland (1788–1854), a former student of Benjamin Latrobe (1764–1820), the man who is often called the first professionally-trained American architect. Latrobe and Strickland were both disciples of the Greek Revival style. Strickland would go on to design many other American public buildings in this style, including financial structures such as the New Orleans, Dahlonega, Mechanics National Bank (also in Philadelphia) and Charlotte branch mints in the mid-to-late 1830s, as well as the second building for the main U.S. Mint in Philadelphia in 1833.

Strickland's design for the Second Bank of the United States remains fairly straightforward. The hallmarks of the Greek Revival style can be seen immediately in the north and south façades, which use a large set of steps leading up to the main level platform, known as the stylobate. On top of these, Strickland placed eight severe Doric columns, which are crowned by an entablature containing a triglyph frieze and simple triangular pediment. The building appears much as an ancient Greek temple, hence the stylistic name. The interior consists of an entrance hallway in the center of the north façade flanked by two rooms on either side. The entry leads into two central rooms, one after the other, that span the width of the structure east to west. The east and west sides of the first large room are each pierced by large arched fan window. The building's exterior uses Pennsylvania Blue Marble, which, due to the manner in which it was cut, has begun to deteriorate from the exposure to the elements of weak parts of the stone.[117] This phenomenon is most visible on the Doric columns of the south façade. Construction lasted from 1819 to 1824.

The Greek Revival style used for the Second Bank contrasts with the earlier, Federal style in architecture used for the First Bank, whose building also still stands and is located nearby in Philadelphia. This can be seen in the more Roman-influenced Federal structure's ornate, colossal Corinthian columns of its façade, which is also embellished by Corinthian pilasters and a symmetric arrangement of sash windows piercing the two stories of the façade. The roofline is also topped by a balustrade and the heavy modillions adorning the pediment give the First Bank an appearance much more like a Roman villa than a Greek temple.

Current building use

Since the bank's closing in 1841, the edifice has performed a variety of functions. As of 2006, it is included as one of the main structures in Independence National Historical Park in downtown Philadelphia, alongside many other important early American structures such as Independence Hall and the Philadelphia Merchants' Exchange.

The structure is open daily free of charge and serves as an art gallery, housing a large and famous collection of portraits of prominent early Americans painted by Charles Willson Peale and many others.

See also

- Banking in the Jacksonian Era

- Federal Reserve Act

- History of central banking in the United States

- Panic of 1837

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 15, 2006.

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 149

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 76-77

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 155

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p.149

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 12

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p.149-150

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 10-11

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 155

- ^ Hammond, 1956, p. 9

- ^ Remini, 1993, p.140

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 205

- ^ Remini, 1993, p. 145

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 365

- ^ Meyer, 1953, p. 212-213

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 115-116

- ^ Hammond, 1956, p. 100

- ^ Hammond, 1957, p. 359

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 155

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 401

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 157

- ^ Hammond, 1956, p. 10

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p.88-89

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 181

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 204-205

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 149

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 10

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 10

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 182

- ^ Remini, 1993, p.140

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 181

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 11

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 203, p. 205

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 10-11

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p.11-12

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p.11

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 32

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p.20-21

- ^ Varon, 2008, p. 36

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 203, p. 214

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 150

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 87

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 152

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 203-204

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p.153

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 206

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 206

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 76

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 73-74

- ^ Hofstadter, 1948, p.55-56

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 205-206, p. 207

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 80-81, p. 85

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 28

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 206

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 86, p. 89

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 84

- ^ Dangerfield, p. 81, p. 83

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 80

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 85-86

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 84

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p.207-208

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 89

- ^ Dangerfield, 1966, p. 89

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 151

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 229

- ^ Hofstadter, 1948, p. 62

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p.150

- ^ Hammon, 1947, p. 151

- ^ Hammond, 1957, p. 371

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 77

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 362

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 151-152

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 228-229, p. 303

- ^ Hammond, 1957, p. 377-378

- ^ Hammond, 1957, p. 379

- ^ Hofstadter, 1948, p. 59-60

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 81

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 301-302

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 362

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 341-342

- ^ Hammond, 1957, p. 385

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 365

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 369

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 343

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 87

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 361

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 374

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 91

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p.87

- ^ Wellman, 1966, p. 132

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 382-383, p. 389

- ^ Remini, 1981, p. 375-376

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 392-393

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 98

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 155

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 151

- ^ Hofstadter, 1948, p. 61-62

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 396

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 103

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 400

- ^ Schlesinger, 1945, p. 112-113

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 401

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 155

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 157

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 150

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 74-75

- ^ Hofstadter, 1948, p. 56

- ^ Wilentz, 2008, p. 205

- ^ Wilentz, 2008, p. 205

- ^ Hammond, 1956, p. 9-10

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 149-150

- ^ Hofstadter, 1948, p. 56

- ^ Wilentz, 2008, p. 205

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 150

- ^ Hammond, 1947, p. 153

- ^ Wilentz, 2005, p. 205

- ^ "Pennsylvania Blue Marble". Second Bank of the United States. National Park Service.

References

- McGrane, Reginald C. Ed. The Correspondence of Nicholas Biddle (1919)

- Hofstadter, Richard. Great Issues in American History: From the Revolution to the Civil War, 1765–1865 (1958).

- Bodenhorn, Howard. A History of Banking in Antebellum America: Financial Markets and Economic Development in an Era of Nation-Building (2000). Stresses how all banks promoted faster growth in all regions.

- Daniel Feller, "The bank war," in Julian E. Zelizer, ed. The American Congress (2004), pp 93–111.

- Govan, Thomas Payne (1959). Nicolas Biddle, Nationalist and Public Banker, 1786–1844. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Hammond, Bray. "Jackson, Biddle, and the Bank of the United States," The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 7, No. 1 (May, 1947), pp. 1–23 at JSTORin Essays on Jacksonian America, Ed. Frank Otto Gatell. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. New York. 1970.

- Hammond, Bray. 1957. Banks and Politics in American, from the Revolution to the Civil War. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

- Hammond, Bray. 1953. "The Second Bank of the United States. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Ser., Vol. 43, No. 1 (1953), pp. 80–85 in JSTOR

- Meyers, Marvin. 1953. The Jacksonian Persuasion. American Quarterly Vol. 5 No. 1 (Spring, 1953) in Essays on Jacksonian America, Ed. Frank Otto Gatell. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. New York.

- Ratner, Sidney, James H. Soltow, and Richard Sylla. The Evolution of the American Economy: Growth, Welfare, and Decision Making. (1993)

- Remini Robert V. Andrew Jackson and the Bank War: A Study in the Growth of Presidential Power (1967).

- Remini, Robert V. 1981. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822-1832. vol. II. Harper & Row, New York.

- Remini, Robert V. 1984. Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1833-1845. vol. III. Harper & Row, New York.

- Remini, Robert. V. 1993. Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union. W. W. Norton & Company, New York.

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier Jr. Age of Jackson (1946). Pulitzer prize winning intellectual history; strongly pro-Jackson.

- Schweikart, Larry. Banking in the American South from the Age of Jackson to Reconstruction (1987)

- Taylor; George Rogers, ed. Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States (1949).

- Temin, Peter. The Jacksonian Economy (1969)

- Varon, Elizabeth R. Disunion!: The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859. Chapel Hill [N.C.]: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

- Wellman, Paul I. 1984. The House Divides: The Age of Jackson and Lincoln. Doubleday and Company, Inc., New York.

- Wilburn, Jean Alexander. Biddle's Bank: The Crucial Years (1967).

- Wilentz, Sean. 2008. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. W.W. Horton and Company. New York.

External links

- First and Second Banks of the United States – a digital collection of the original documents related to the formation of the First (1791–1811) and Second (1816–1836) Banks of the United States, digitized by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- Second Bank – official site at Independence Hall National Historical Park]

- The Second Bank of the United States – a history of the Bank by Ralph C. H. Catterall of the University of Chicago, 1902 – on Google Books

- Andrew Jackson on the Web : Bank of the United States

- Banks based in Pennsylvania

- Economic history of the United States

- Buildings and structures completed in 1824

- National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

- Defunct banks of the United States

- 1841 disestablishments

- Presidency of Andrew Jackson

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- Greek Revival architecture in Pennsylvania

- Buildings and structures in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Buildings and structures in Independence National Historical Park

- Banks established in 1816

- Presidency of James Madison

- Defunct companies based in Pennsylvania

- Companies disestablished in the 19th century

- 14th United States Congress

- Museums in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Art galleries in Pennsylvania

- 1816 establishments in the United States