Codex

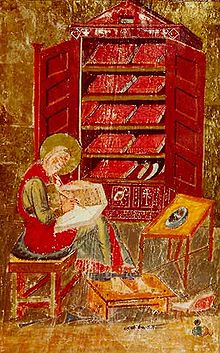

A codex (Latin caudex for "trunk of a tree" or block of wood, book; plural codices) is a book made up of a number of sheets of paper, vellum, papyrus, or similar, with hand-written content,[1] usually stacked and bound by fixing one edge and with covers thicker than the sheets, but sometimes continuous and folded concertina-style. The alternative to paged codex format for a long document is the continuous scroll. Examples of folded codices are the Maya codices. Sometimes the term is used for a book-style format, including modern printed books but excluding folded books.

Developed by the Romans from wooden writing tablets, its gradual replacement of the scroll, the dominant form of book in the ancient world, has been termed the most important advance in the history of the book prior to the invention of printing.[2] The codex altogether transformed the shape of the book itself and offered a form that lasted for centuries.[3] The spread of the codex is often associated with the rise of Christianity, which adopted the format for the Bible early on.[4] First described by the 1st-century AD Roman poet Martial, who praised its convenient use, the codex achieved numerical parity with the scroll around AD 300, and had completely replaced it throughout the now Christianised Greco-Roman world by the 6th century.[5]

The codex holds considerable practical advantages over other book formats, such as compactness, sturdiness, ease of reference (a codex is random access, as opposed to a scroll, which is sequential access), and especially economy of materials; unlike the scroll, both recto and verso could be used for writing.[6] Although the change from rolls to codices roughly coincides with the transition from papyrus to parchment as favourite writing material, the two developments are quite unconnected. In fact, any combination of codices and scrolls on the one hand with papyrus and parchment on the other is technically feasible and well attested from the historical record.[7]

Although technically even modern paperbacks are codices, the term is now used only for manuscript (hand-written) books which were produced from Late antiquity until the Middle Ages. The scholarly study of these manuscripts from the point of view of the bookbinding craft is called codicology; the study of ancient documents in general is called paleography.

History

The Romans used precursors made of reusable wax-covered tablets of wood for taking notes and other informal writings. Two ancient polyptychs, a pentatych and octotych, excavated at Herculaneum employed a unique connecting system that presages later sewing on thongs or cords.[8] Julius Caesar may have been the first Roman to reduce scrolls to bound pages in the form of a note-book, possibly even as a papyrus codex.[9] At the turn of the 1st century AD, a kind of folded parchment notebook called pugillares membranei in Latin became commonly used for writing in the Roman Empire.[10] This term was used by both the Classical Latin poet Martial and the Christian apostle Paul.[11][12] Martial used the term with reference to gifts of literature exchanged by Romans during the festival of Saturnalia. According to T.C. Skeat “…in at least three cases and probably in all, in the form of codices" and he theorized that this form of notebook was invented in Rome and then “…must have spread rapidly to the Near East…”[13] In his discussion of one of the earliest parchment codices to survive from Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, Eric Turner seems to challenge Skeat’s notion when stating “…its mere existence is evidence that this book form had a prehistory” and that “early experiments with this book form may well have taken place outside of Egypt.”[14] Early codices of parchment or papyrus appear to have been widely used as personal notebooks, for instance in recording copies of letters sent (Cicero Fam. 9.26.1). The pages of parchment notebooks were commonly washed or scraped for re-use, called a palimpsest; and consequently writings in a codex were considered informal and impermanent.

As far back as the early 2nd century, there is evidence that the codex—usually of papyrus—was the preferred format among Christians: in the library of the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum (buried in AD 79), all the texts (Greek literature) are scrolls (see Herculaneum papyri); in the Nag Hammadi "library", secreted about AD 390, all the texts (Gnostic Christian) are codices. Despite this comparison, a fragment of a non-Christian parchment Codex of Demosthenes, De Falsa Legatione from Oxyrhynchus in Egypt demonstrates that the surviving evidence is insufficient to conclude whether Christians played a major, if not central, role in the development of early codices, or if they simply adopted the format to distinguish themselves from Jews. The earliest surviving fragments from codices come from Egypt and are variously dated (always tentatively) towards the end of the 1st century or in the first half of the 2nd. This group includes the Rylands Library Papyrus P52, containing part of St John's Gospel, and perhaps dating from between 125 and 160.[15]

In Western culture the codex gradually replaced the scroll. From the 4th century, when the codex gained wide acceptance, to the Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th century, many works that were not converted from scroll to codex were lost to posterity. The codex was an improvement over the scroll in several ways. It could be opened flat at any page, allowing easier reading; the pages could be written on both front and back (recto and verso); and the codex, protected within its durable covers, was more compact and easier to transport.

The codex also made it easier to organize documents in a library because it had a stable spine on which the title of the book could be written. The spine could be used for the incipit, before the concept of a proper title was developed, during medieval times.

Although most early codices were made of papyrus, papyrus was fragile and supplies from Egypt, the only place where papyrus grew and was made into paper, became scanty; the more durable parchment and vellum gained favor, despite the cost.

The codices of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica had the same form as the European codex, but were instead made with long folded strips of either fig bark (amatl) or plant fibers, often with a layer of whitewash applied before writing. New World codices were written as late as the 16th century (see Maya codices and Aztec codices). Those written before the Spanish conquests seem all to have been single long sheets folded concertina-style, sometimes written on both sides of the local amatl paper.

In the Far East, the scroll remained standard for far longer than in the West. There were intermediate stages, such as scrolls folded concertina-style and pasted together at the back and books that were printed only on one side of the paper.[16] Judaism still retains the Torah scroll, at least for ceremonial use.

Bookbinding

Among the experiments of earlier centuries, scrolls were sometimes unrolled horizontally, as a succession of columns. (The Dead Sea Scrolls are a famous example of this format.) This made it possible to fold the scroll as an accordion. The next step was then to cut the folios, sew and glue them at their centers, making it easier to use the papyrus or vellum recto-verso as with a modern book. In traditional bookbinding, these assembled folios trimmed and curved were called "codex" in order to differentiate it from the "case" which we now know as "hard cover". Binding the codex was clearly a different procedure from binding the "case". This terminology, still in use some 50 or 60 years ago,[citation needed] has been nearly abandoned. Some commercial bookbinders may refer to the cover and the inside of the book instead, but a few others[who?], attached to their traditions, still use the terms "codex" and "case".

See also

- List of codices

- List of New Testament papyri

- List of New Testament uncials

- Aztec codices

- Maya codices

- Traditional Chinese bookbinding

- History of books

References

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed: Codex: "a manuscript volume"

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, p. 1 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFRobertsSkeat1983 (help)

- ^ Lyons, M., (2011). Books: A Living History, London: Thames & Hudson, p. 8

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, pp. 38−67 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFRobertsSkeat1983 (help)

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, p. 75 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFRobertsSkeat1983 (help)

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, pp. 45−53 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFRobertsSkeat1983 (help)

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, p. 5 harvnb error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFRobertsSkeat1983 (help)

- ^ Carratelli, Giovanni Pugliese (1950). "L'instrvmentvm Scriptorivm Nei Monumenti Pompeiani Ed Ercolanesi." in Pompeiana. Raccolta di studi per il secondo centenario degli di Pompei. pp. 166–78.

- ^ During the Gallic Wars; Suet. Jul. 56.6; cf. Roberts, Colin H.; Skeat, Theodore Cressy (1983), The Birth of the Codex, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 18 sq., ISBN 0-19-726061-6

- ^ Roberts, Colin H; Skeat, TC (1983). The Birth of the Codex. London: British Academy. pp. 15–22. ISBN 0-19-726061-6.

- ^ E. Randolph Richards, Paul and First-Century Letter Writing: Secretaries, Composition and Collection

- ^ "2 Timothy 4:13 NRSVACE - When you come, bring the cloak that I". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ^ Skeat, T.C. (2004). The Collected Biblical Writings of T.C. Skeat. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 45. ISBN 90-04-13920-6.

- ^ Turner, Eric (1977). The Typology of the Early Codex. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8122-7696-1.

- ^ Turner The Typology of the Early Codex, U Penn 1977, and Roberts & Skeat The Birth of the Codex (Oxford University 1983). From Robert A Kraft (see link): "A fragment of a Latin parchment codex of an otherwise unknown historical text dating to about 100 CE was also found at Oxyrhynchus (P. Oxy. 30; see Roberts & Skeat 28). Papyrus fragments of a "Treatise of the Empirical School" dated by its editor to the centuries 1–2 CE is also attested in the Berlin collection (inv. # 9015, Pack\2 # 2355)—Turner, Typology # 389, and Roberts & Skeat 71, call it a "medical manual.""

- ^ International Dunhuang Project—Several intermediate Chinese bookbinding forms from the 10th century.

Sources

- David Diringer, The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental, Courier Dover Publications, New York 1982, ISBN 0-486-24243-9

- L. W. Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins, Cambridge 2006.

- Roberts, Colin H.; Skeat, T. C. (1983), The Birth of the Codex, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-726024-1

External links

- Georgian Codex

- Centre for the History of the Book

- The Codex and Canon Consciousness – Draft paper by Robert Kraft on the change from scroll to codex

- The Construction of the Codex In Classic- and Postclassic-Period Maya Civilization Maya Codex and Paper Making

- Encyclopaedia Romana: "Scroll and codex"

- K.C. Hanson, Catalogue of New Testament Papyri & Codices 2nd—10th Centuries

- Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, including Vulgates, Breviaries, Contracts, and Herbal Texts from 12 -17th century, Center for Digital Initiatives, University of Vermont Libraries