Things Fall Apart

This article needs more links to other articles to help integrate it into the encyclopedia. (March 2013) |

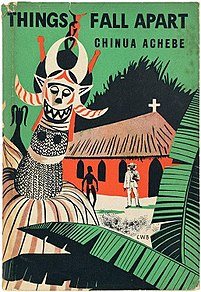

First edition | |

| Author | Chinua Achebe |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | C. W. Barton |

| Language | English |

| Genre | historical fiction |

| Publisher | William Heinemann Ltd. |

Publication date | 1958 |

| Publication place | Nigeria |

Things Fall Apart is an English-language novel by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe published in 1958 by William Heinemann Ltd in the UK. It is seen as the archetypal modern African novel in English, one of the first to receive global critical acclaim. It is a staple book in schools throughout Africa and is widely read and studied in English-speaking countries around the world. The title of the novel comes from William Butler Yeats' poem "The Second Coming".[1]

The novel shows the life of Okonkwo, a leader and local wrestling champion in Umuofia—one of a fictional group of nine villages in Nigeria, inhabited by the Igbo people (in the novel, "Ibo"). It describes his family and personal history, the customs and society of the Igbo, and the influence of British colonialism and Christian missionaries on the Igbo community during the late nineteenth century.

Things Fall Apart was followed by a sequel, No Longer at Ease (1960), originally written as the second part of a larger work along with Arrow of God (1964). Achebe states that his two later novels, A Man of the People (1966) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987), while not featuring Okonkwo's descendants, are spiritual successors to the previous novels in chronicling African history.

Plot

Set in pre-colonial Nigeria in the 1890s, Things Fall Apart highlights the clash between colonialism and traditional culture. The protagonist Okonkwo is strong, hard-working, and strives to show no weakness. Okonkwo wants to dispel his father Unoka’s tainted legacy of being cheap (he borrowed and lost money, and neglected his wife and children) and cowardly (he feared the sight of blood). Okonkwo works to build his wealth entirely on his own, as Unoka died a shameful death and left many unpaid debts. Although brusque with his three wives, children, and neighbours, he is wealthy, courageous, and powerful among the people of his village. He is a leader of his village, and he has attained a position in his society for which he has striven all his life.

Because of the great esteem in which the village holds him, Okonkwo is selected by the elders to be the guardian of Ikemefuna, a boy taken by the village as a peace settlement between Umuofia and another village after Ikemefuna's father killed an Umuofian woman. The boy lives with Okonkwo's family and Okonkwo grows fond of him. The boy looks up to Okonkwo and considers him a second father. The Oracle of Umuofia eventually pronounces that the boy must be killed. Ezeudu, the oldest man in the village, warns Okonkwo that he should have nothing to do with the murder because it would be like killing his own child. But to avoid seeming weak and feminine to the other men of the village, Okonkwo participates in the murder of the boy despite the warning from the old man. In fact, Okonkwo himself strikes the killing blow even as Ikemefuna begs his "father" for protection. However, for many days after killing Ikemefuna, Okonkwo feels guilty and saddened by this.

Shortly after Ikemefuna's death, things begin to go wrong for Okonkwo. During a gun salute at Ezeudu's funeral, Okonkwo's gun explodes and kills Ezeudu's son. He and his family are sent into exile for seven years to appease the gods he has offended. While Okonkwo is away, white men begin to arrive in Umuofia with the intent of introducing their religion. As the number of converts increases, the foothold of the white people grows and a new government is introduced. The village is forced to respond with either appeasement or conflict to the imposition of the white people's nascent society.

Returning from exile, Okonkwo finds his village a changed place because of the presence of the white men. He and other tribal leaders try to reclaim their hold on their native land by destroying a local Christian church. In return, the leader of the white government takes them prisoner and holds them for ransom for a short while, further humiliating and insulting the native leaders. As a result, the people of Umuofia finally gather for what could be a great uprising. Okonkwo, a warrior by nature and adamant about following Umuofian custom and tradition, despises any form of cowardice and advocates for war against the white men. When messengers of the white government try to stop the meeting, Okonkwo kills one of them. He realizes with despair that the people of Umuofia are not going to fight to protect themselves — his society's response to such a conflict, which for so long had been predictable and dictated by tradition, is changing.

When the local leader of the white government comes to Okonkwo's house to take him to court, he finds that Okonkwo has hanged himself. He ultimately commits suicide rather than be tried in a colonial court. Among his own people, Okonkwo's action has ruined his reputation and status, as it is strictly against the teachings of the Igbo to commit suicide.

Characters

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2012) |

- Okonkwo is the novel's protagonist. He has three wives and eight children, and is a brave and rash Umuofian (Nigerian) warrior and clan leader. Unlike most, he cares more for his daughter (Ezinma) than his son, Nwoye (who is later called Isaac), who he believes is weak. Okonkwo is the son of the effeminate and lazy Unoka, a man he resents for his weaknesses. Okonkwo strives to make his way in a culture that traditionally values manliness. As a young man he defeated the village's best wrestler, earning him lasting prestige. He therefore rejects everything for which he believes his father stood: Unoka was idle, poor, profligate, cowardly, gentle, and interested in music and conversation. Okonkwo consciously adopts opposite ideals and becomes productive, wealthy, brave, violent, and opposed to music and anything else that he regards as "soft," such as conversation and emotion. He is stoic to a fault. He is also the hardest-working member of his clan. Okonkwo's life is dominated by fear of failure and of weakness—the fear that he will resemble his father. Ironically, in all his efforts not to end up like his father, he commits suicide, becoming in his culture an abomination to the Earth and rebuked by the tribe as his father was (Unoka died from swelling and was likewise considered an abomination). Okonkwo's suicide represents not only his culture's rejection of him, but his rejection of the changes in his people's culture, as he realizes that the Igbo society that he so valued has been forever altered by the Christian missionaries.

- Unoka is Okonkwo's father, who lived a life in contrast to typical Igbo masculinity. He loved language and music, the flute in particular. He is lazy and miserly, neglecting to take care of his wives and children and even dies with unpaid debts. Okonkwo spends his life trying not to become a failure like his father Unoka.

- Nwoye is Okonkwo's son, about whom Okonkwo worries, fearing that he will become like Unoka. Similar to Unoka, Nwoye does not ascribe to the traditional Igbo view of masculinity being equated to violence; rather, he prefers the stories of his mother. Nwoye connects to Ikemefuma, who presents an alternative to Okonkwo's rigid masculinity. He is one of the early converts to Christianity with the arrival of the missionaries, an act which Okonkwo views as a final betrayal.

- Ikemefuna is a boy from the Mbaino tribe. He is given to Okonkwo in a settlement when an Mbaino tribesman murders the wife of an Umofian. Ikemefuna is ultimately murdered, an act which Okonkwo does not prevent, and even participates in, for fear of seeming not masculine.

- Ezinma is Okonkwo's favorite daughter, and the only child of his wife Ekwefi. Ezinma is very much the antithesis of a normal woman within the culture and Okonkwo routinely remarks that she would've made a much better boy than a girl, even wishing that this was the case of her birth. Ezinma often contradicts and challenges her father, which wins his adoration, affection, and respect. She is very similar to her father, and this is made apparent when she matures into a beautiful young woman who refuses to marry during her family's exile, instead choosing to help her father regain his place of respect within society.

Background

Most of the story takes place in the village of Umuofia, located west of the actual city of Onitsha, on the east bank of the Niger River in Nigeria. The events of the novel unfold in the 1890s.[2] The culture depicted, that of the Igbo people, is similar to that of Achebe's birthplace of Ogidi, where Igbo-speaking people lived together in groups of independent villages ruled by titled elders. The customs described in the novel mirror those of the actual Onitsha people, who lived near Ogidi, and with whom Achebe was familiar.

Within forty years of the arrival of the British, by the time Achebe was born in 1930, the missionaries were well established. Achebe's father was among the first to be converted in Ogidi, around the turn of the century. Achebe himself was an orphan raised by his grandfather. His grandfather, far from opposing Achebe's conversion to Christianity, allowed Achebe's Christian marriage to be celebrated in his compound.[2]

Language choice

Achebe writes his novels in English because written Standard Igbo was created by combining various dialects, creating a stilted written form. In a 1994 interview with The Paris Review, Achebe said, "the novel form seems to go with the English language. There is a problem with the Igbo language. It suffers from a very serious inheritance which it received at the beginning of this century from the Anglican mission. They sent out a missionary by the name of Dennis. Archdeacon Dennis. He was a scholar. He had this notion that the Igbo language—which had very many different dialects—should somehow manufacture a uniform dialect that would be used in writing to avoid all these different dialects. Because the missionaries were powerful, what they wanted to do they did. This became the law. But the standard version cannot sing. There's nothing you can do with it to make it sing. It's heavy. It's wooden. It doesn't go anywhere."[3]

Achebe's choice to write in English has caused controversy. While both African and non-African critics agree that Achebe modeled Things Fall Apart on classic European literature, they disagree about whether his novel upholds a Western model, or, in fact, subverts or confronts it.[4] Achebe has continued to defend his decision: "English is something you spend your lifetime acquiring, so it would be foolish not to use it. Also, in the logic of colonization and decolonization it is actually a very powerful weapon in the fight to regain what was yours. English was the language of colonization itself. It is not simply something you use because you have it anyway."[5]

Achebe is noted for his inclusion of and weaving in of proverbs from Igbo oral culture into his writing.[6] This influence was explicitly referenced by Achebe in Things Fall Apart: "Among the Igbo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm-oil with which words are eaten."

Themes and motifs

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2012) |

Themes in the novel include the relationship between the individual (Okonkwo) and his culture, and the effect of one culture visited upon another.

- Individuals gain strength from their society or community, and societies derive strength from the individuals who belong to them. In Things Fall Apart, Okonkwo builds his titles and strength with the support of his society's customs. Likewise, Okonkwo's community profits from his hard work and willpower to remain strong.

- In contacts between other cultures, beliefs about superiority or inferiority, due to limited and partial world view, are invariably wrong-headed and destructive. When new cultures and religions meet the original, there is likely to be a struggle for dominance. For example, the Christians and Okonkwo's people have a limited view of each other, and have a very difficult time understanding and accepting one another's customs and beliefs, which result in violence as with the destruction of a local church and Okonkwo's killing of the messenger.

- In spite of innumerable opportunities for understanding, people must strive to communicate. For example, Okonkwo and his son Nwoye have a difficult time understanding one another because they hold different values. On the other hand, Okonkwo spends more time with Ikemefuna and develops a deeper relationship that seems to go beyond cultural restraints.

- A social value—such as individual ambition—which is constructive when balanced by other values, can become destructive when overemphasized at the expense of other values. For example, Okonkwo values tradition so highly that he cannot accept change. (It may be more accurate to say he values tradition because of the high price he has paid to uphold it, i.e. killing Ikemefuna and moving to Mbanta). The Christian teachings render these considerable sacrifices on his part meaningless. The distress over the loss of tradition, whether driven by his love of the tradition or the meaning of his sacrifices to it, can be seen as the main reasons for his suicide.

- Culture is not static; change is continual, and flexibility is necessary for successful adaptation. Because Okonkwo cannot accept the change the Christians bring, he cannot adapt.[7]

- The struggle between change and tradition is constant; however, this statement only appears to apply to Okonkwo. Change can very well be accepted, as evidenced by how the people of Umuofia refuse to join Okonkwo as he strikes down the white man's messenger, a kotma, at the end. Perhaps Okonkwo is not so much bothered by change, but the idea of losing everything he has built up, such as his fortune, prestige, and title, which will be replaced by new values. It is evidenced throughout the book that he cares deeply about these things, exemplified in his feelings of regret that he has lacked a "respectable" father figure from whom he could have inherited them.[7] A second interpretation is apparent with Okonkwo's static behavior to cultural change. His suicide can be seen as a final attempt to show to the people of Umuofia the results of a clash between cultures and as a plea for the Igbo culture to be upheld. In the same way that his father's failure motivated Okonkwo to reach a high standing in the Igbo society, Okonkwo's suicide leads Obierika and fellow Umuofia men to recognize the long-held custom of refraining from burying a man who commits suicide and from performing the customary rituals. This interpretation is further emphasized with Obierika's comment on Okonkwo as a great man driven to kill himself as a result of the pain springing from the loss of his society's traditions. Thus, Okonkwo's killing of the messenger and subsequent suicide embodies the internal struggle between change and tradition.

- The role of culture in society. With the death of Ikemefuna, Okonkwo's expulsion due to events beyond his control and the journey of Ezinma with Chielo, Achebe questions, particularly through Obierika, whether adherence to culture is for the benefit of society when it brings about so many hardships and sacrifices on the part of Okonkwo and his family.

- Notion of success and failure. Okonkwo's personal ambition to avoid a life of "failure" similar to his father, Unoka, leads to his high title and affluence in the community. He ardently tries to avoid failure. The notion of failure draws a parallel with the idea of cultural alteration in Umuofia and a shift in cultural values. Failure, for Okonkwo, is societal reform, hence Okonkwo's drastic, and at times unpredictable, exploits in opposition to anything foreign or lacking in what he perceives to be masculine traits.

- Through Achebe's use of language, he is successful in demonstrating (and attesting to) the Igbo's rich and unique culture. By integrating traditional Igbo words (e.g. egwugwu, or the spirits of the ancestor's of Nigerian tribes), folktales, and songs into English sentences, the author is successful in proving that African languages aren't incomprehensible, although they are often too complex for direct translation into English. Additionally, the author is successful in verifying that each of the continent's languages is unique, as Mr. Brown's translator is ridiculed after his misinterpretation of an Igbo word.

Culture

Prior to British colonization, the Igbo people as depicted in Things Fall Apart lived in a patriarchal collective political system. Decisions were not made by a chief or by any individual but rather by a council of male elders. Religious leaders were also called upon to settle debates reflecting the cultural focus of the Igbo people. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to explore Nigeria. Though the Portuguese are not mentioned by Achebe, their enduring influence can be seen in many Nigerian surnames. The British entered Nigeria first through trade and then established The Royal Niger Colony in 1886. The success of the colony led to Nigeria's becoming a British protectorate in 1901. The arrival of the British slowly began to destroy the traditional society. The British government would intervene in tribal disputes rather than allow the Igbo to settle issues in a traditional manner. The frustration caused by these shifts in power is illustrated by the struggle of the protagonist Okonkwo in the second half of the novel.

Despite converting to Christianity himself, Achebe wrote Things Fall Apart not only in response to the then-common misrepresentations of his native people, but to show the dignity of the Igbo to his fellow citizens. His depiction of the Igbo people's democratic institutions and culture allow them to be tested "against the goals of modern liberal democracy and to have set out to show how the Igbo meet those standards."[8] While the Europeans in Things Fall Apart are depicted as intolerant of Igbo culture and religion, telling villagers that their gods are not real (pp. 135, 162) the Igbo are seen as tolerant of other cultures as a whole. For example, Uchendu is able to see that "what is good among one people is an abomination with others" (p. 129).

However, the novel does not idealize the Igbo people; Achebe also intends to show readers what fractures existed within their culture. He "presents its weaknesses which require change and which aid in its destruction."[8] They fear twins, who are to be abandoned immediately after birth and left to die of exposure.

The novel attempts to repair some of the damage done by earlier European depictions of Africans. Achebe "chooses to ignore the evidence of what Izevbaye calls 'rich material civilization' in Africa in order to portray the Igbo as isolated and unique, evolving their own 'humanistic civilization'."[9] This suggests that Achebe intended to show readers the changes that the Igbo culture could have made in order to survive in future years.[10]

Achebe shows that European sentiments toward Africans are mistaken. According to Diana Akers Rhoads, "Perhaps the most important mistake of the British is their belief that all civilization progresses, as theirs has, from the tribal stage through monarchy to parliamentary government. On first arriving in Mbanta, the missionaries expect to find a king (p. 138), and, discovering no functionaries to work with, the British set up their own hierarchical system which delegates power from the queen of England through district commissioners to native court messengers — foreigners who do not belong to the village government at all (p. 160). Since the natives from other parts of Nigeria feel no loyalty to the villages where they enact the commands of the district commissioners, the British have superimposed a system which leads to bribery and corruption rather than to progress."[11] By contrast, the Igbo follow a democracy which judges each man according to his personal merit.

Gender

Definitions of masculinity vary in different societies. Gender differentiation is seen in Igbo classification of crimes. The narrator of Things Fall Apart states that "the crime [of murder] was of two kinds, male and female. Okonkwo had committed the female because it was an accident. He would be allowed to return to the clan after seven years."[12] Okonkwo flees to the land of his mother, Mbanta, because a man finds refuge with his mother. In fact, Achebe makes an insightful comment on the nature of masculinity through his representation of the tribal leaders. Basically, this is conducive to creating exactly four alter egos of Okonkwo: one, his masculinity; two, his fatherly abilities; three, his family progress; and four, his likelihood of success. The creation of these egos of Okonkwo further develop Achebe's theme of masculinity. Uchendu explains this to Okonkwo:

"It is true that a child belongs to his father. But when the father beats his child, it seeks sympathy in its mother's hut. A man belongs to his fatherland when things are good and life is sweet. But when there is sorrow and bitterness, he finds refuge in his motherland. Your mother is there to protect you. She is buried there. And that is why we say that mother is supreme."[13]

Religion, myth and history

The analysis of cultural history involves myths, religion, totems, superstitions, rituals, festivals, and icons. In Things Fall Apart, the mask, the earth, the legends and the rituals all have significance in the story as well as in the history of the Igbo culture. According to Gordon Baldwin: "Religion looms large in the life of primitive man. It is not a one-a-day-a-week affair as it generally is with us. Seven days a week, 365 days a year, primitive peoples eat and work and play and sleep with religion. Nearly everything in primitive society — hunting, fishing, planting crops, harvesting, head hunting, war, marriage, birth, coming of age, illness, death, building a house, making a canoe or an ax — is associated with ritual or magic or ceremony or some other form of religious activity."[14]

First, there is the use of the mask to draw the spirit of the gods into the body of a person. A great crime in Ibo culture is to unmask or show disrespect to the immortality of an egwugwu, which represents an ancestral spirit. Toward the end of the novel, a warrior converted into a Christian unmasks and kills one of his own ancestral spirits. The clan weeps, for "it seemed as if the very soul of the tribe wept for a great evil that was coming — its own death."[15]

In the cultural history of Nigeria complex rituals also played a large part in the daily life of the people. Achebe's story reflects this strict attention to rituals and taboos. Okonkwo upholds his traditions by helping to kill the boy sacrificed to settle a dispute with another tribe, despite his paternal feelings towards the boy. Okonkwo kills Ikemefuna because "he was afraid of being thought weak."[16] Yet, afterwards he cannot eat or sleep, "he felt like a drunken giant walking with the limbs of a mosquito."[17] The space between an individual identity and his ancestors is narrow. In fact, Achebe goes so far as to say: "The land of the living was not far removed from the domain of the ancestors. There was coming and going between them, especially at festivals and also when an old man died, because an old man was very close to the ancestors. A man's life from birth to death was a series of transition rites which brought him nearer and nearer to his ancestors."[18]

There are several legends and myths told in Things Fall Apart: the earth and the sky;[19] the mosquito and the ear;[20] the tortoise and the birds.[21] According to Rosenberg, "myths symbolize human experience and embody the spiritual values of a culture."[22] The values and views of the world spread through mythology are important to the survival of every society's culture.[23] Myths are instructional as well as entertaining. Myths "explain the nature of the universe (creation and fertility myths)... or instruct members of the community in the attitudes and behavior necessary to function successfully in that particular culture (hero myths and epics)."[24] In Things Fall Apart, the use of language shares the functions of myths; "Among the Ibo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm oil with which words are eaten."[25] Proverbs and myths are both ways of conveying a meaning without directly force-feeding the words to the listener. Achebe is showing the importance of stories even within the story he is telling.

Things Fall Apart has been called a modern Greek tragedy. It has the same plot elements as a Greek tragedy, including the use of a tragic hero, the following of the string model, etc. Okonkwo is a classic tragic hero, even though the story is set in more modern times. He shows multiple hamartia, including hubris (pride) and ate (rashness), and these character traits do lead to his peripeteia, or reversal of fortune, and to his downfall at the end of the novel. He is distressed by social changes brought on by the white men because he has worked so hard to move up in the traditional society. Okonkwo's position is at risk due to the arrival of a new value system. Those who commit suicide lose their place in the ancestor-worshipping traditional society, to the extent that they may not even be touched in order to receive a proper burial. The irony is that Okonkwo completely loses his standing in both value systems. Okonkwo truly has good intentions, but his need to be in control and his fear that other men will sense weakness in him drive him to make decisions, whether consciously or subconsciously, that he regrets as he progresses through his life.[26]

Literary significance and reception

Things Fall Apart is a milestone in African literature. It has come to be seen as the archetypal modern African novel in English,[2][5] and is read in Nigeria and throughout Africa. Of all of Achebe's works, Things Fall Apart is the one read most often, and has generated the most critical response, examination, and literary criticism. It is studied widely in Europe and North America, where it has spawned numerous secondary and tertiary analytical works. It has achieved similar status and repute in India, Australia and Oceania.[2] Considered Achebe's magnum opus, it has sold more than 8 million copies worldwide.[27] Time Magazine included the novel in its TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[28] The novel has been translated into more than fifty languages, and is often used in literature, world history, and African studies courses across the world.

Achebe is now considered to be the essential novelist on African identity, nationalism, and decolonization. Achebe's main focus has been cultural ambiguity and contestation. The complexity of novels such as Things Fall Apart depends on Achebe's ability to bring competing cultural systems and their languages to the same level of representation, dialogue, and contestation.[5]

Reviewers have praised Achebe's neutral narration and have described Things Fall Apart as a realistic novel. Much of the critical discussion about Things Fall Apart concentrates on the socio-political aspects of the novel, including the friction between the members of Igbo society as they confront the intrusive and overpowering presence of Western government and beliefs. Ernest N. Emenyonu commented that "Things Fall Apart is indeed a classic study of cross-cultural misunderstanding and the consequences to the rest of humanity, when a belligerent culture or civilization, out of sheer arrogance and ethnocentrism, takes it upon itself to invade another culture, another civilization."[29]

Achebe's writing about African society, in telling from an African point of view the story of the colonization of the Igbo, tends to extinguish the misconception that African culture had been savage and primitive. In Things Fall Apart, western culture is portrayed as being "arrogant and ethnocentric," insisting that the African culture needed a leader. As it had no kings or chiefs, Umofian culture was vulnerable to invasion by western civilization. It is felt that the repression of the Igbo language at the end of the novel contributes greatly to the destruction of the culture. Although Achebe favors the African culture of the pre-western society, the author attributes its destruction to the "weaknesses within the native structure." Achebe portrays the culture as having a religion, a government, a system of money, and an artistic tradition, as well as a judicial system.

Influence

The achievement of Things Fall Apart set the foreground for numerous African novelists. Because of Things Fall Apart, novelists after Achebe have been able to find an eloquent and effective mode for the expression of the particular social, historical, and cultural situation of modern Africa.[4] Before Things Fall Apart was published, Europeans had written most novels about Africa, and they largely portrayed Africans as savages who needed to be enlightened by Europeans. Achebe broke apart this view by portraying Igbo society in a sympathetic light, which allows the reader to examine the effects of European colonialism from a different perspective.[4] He commented, "The popularity of Things Fall Apart in my own society can be explained simply... this was the first time we were seeing ourselves, as autonomous individuals, rather than half-people, or as Conrad would say, 'rudimentary souls'."[5]

The language of the novel has not only intrigued critics but has also been a major factor in the emergence of the modern African novel. Because Achebe wrote in English, portrayed Igbo life from the point of view of an African man, and used the language of his people, he was able to greatly influence African novelists, who viewed him as a mentor.[5]

Achebe's fiction and criticism continue to inspire and influence writers around the world. Hilary Mantel, the Booker Prize-winning novelist in a May 7, 2012 article in Newsweek, "Hilary Mantel's Favorite Historical Fictions", lists Things Fall Apart as one of her five favorite novels in this genre. A whole new generation of African writers – Caine prize winners Binyavanga Wainaina (current director of the Chinua Achebe Center at Bard College) and Helon Habila (Waiting for an Angel [2004] and Measuring Tme [2007]); as well as Uzodinma Iweala (Beasts of No Nation [2005]); and Professor Okey Ndibe (Arrows of Rain [2000]) count Chinua Achebe as a significant influence. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the author of the popular and critically acclaimed novels Purple Hibiscus (2003) and Half of a Yellow Sun (2006), commented in a 2006 interview, "Chinua Achebe will always be important to me because his work influenced not so much my style as my writing philosophy: reading him emboldened me, gave me permission to write about the things I knew well."[5]

Film, television, and theatrical adaptations

A dramatic radio program called Okonkwo was made of the novel in April 1961 by the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. It featured Wole Soyinka in a supporting role.[30]

In 1987, the book was made into a very successful miniseries directed by David Orere and broadcast on Nigerian television by the Nigerian Television Authority. It starred several established film actors, including Pete Edochie, Nkem Owoh and Sam Loco.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Washington State University study guide

- ^ a b c d Kwame Anthony Appiah (1992), "Introduction" to the Everyman's Library edition.

- ^ Jerome Brooks, "Chinua Achebe, The Art of Fiction No. 139" (Winter 1994) The Paris Review No. 133

- ^ a b c Booker (2003), p 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Sickels, Amy. "The Critical Reception of Things Fall Apart", in Booker (2011)

- ^ http://www.postcolonialweb.org/achebe/jvrao1.html

- ^ a b "Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe: Introduction." Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Jeffrey W. Hunter. Vol. 152. Gale Cengage, 2002. eNotes.com. 2006. 12 Jan, 2009 <[1]>

- ^ a b Rhoads, p. 61

- ^ Lindfors, Bernth ed. Approaches to Teaching Achebe's Things Fall Apart. New York. 1991

- ^ Rhoads, p. 62

- ^ Rhoads, p. 63

- ^ Achebe Template:P. 124

- ^ Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. EMC Corporation. 2003.

- ^ Baldwin pp. 196–197.

- ^ Achebe, pp. 186–187

- ^ Achebe p. 61.

- ^ Achebe p. 63.

- ^ Achebe p. 122.

- ^ Achebe p. 53

- ^ Achebe p. 75

- ^ Achebe pp. 99–96

- ^ Rosenberg p. xv

- ^ Rosenberg p. xv.

- ^ Rosenberg p. xvi.

- ^ Achebe p. 7.

- ^ Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. EMC Corporation. 2004. Noodle

- ^ Random House Teacher's Guide

- ^ ALL TIME 100 Novels, Time magazine

- ^ Whittaker, David. "Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart" pp 59. New York 2007

- ^ Ezenwa-Ohaeto (1997). Chinua Achebe: A Biography Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33342-3. P. 81.

References

- Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. New York: Anchor Books, 1994. ISBN 0385474547

- Baldwin, Gordon. Strange Peoples and Stranger Customs. New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc, 1967.

- Booker, M. Keith. The Chinua Achebe Encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-325-07063-6

- Booker, M. Keith. Things Fall Apart, by Chinua Achebe [Critical Insights]. Pasadena, Calif: Salem Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-58765-711-5

- Frazer, Sir James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1942.

- Girard, Rene. Violence and the Sacred. Trans. Patrick Gregory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8018-1963-6

- Rhoads, Diana Akers (September 1993). "Culture in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart". African Studies Review. 36(2): 61–72.

- Roberts, J.M. A Short History of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Rosenberg, Donna. World Mythology: An Anthology of the Great Myths and Epics. Lincolnwood, Illinois: NTC Publishing Group, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8442-5765-5

External links

- Chinua Achebe discusses Things Fall Apart on the BBC World Book Club

- Teacher's Guide at Random House

- Study Resource for writing about Things Fall Apart

- Study guide

- Words present in the novel used in past SATs Includes definitions, words in order from the book, and three different tests.

- Things Fall Apart Reviews

- Things Fall Apart on Wiki Summaries

- Things Fall Apart study guide, themes, analysis, teacher resources]

- Things Fall Apart Igbo Culture Guide, Igbo Proverbs]