Porphyria

| Porphyria | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

The porphyrias are a group of rare inherited or acquired disorders of certain enzymes that normally participate in the production of porphyrins and heme. They manifest with either neurological complications or skin problems or occasionally both.

Porphyrias are classified in two ways, by symptoms and by pathophysiology. Symptomatically, acute porphyrias primarily present with nervous system involvement, often with severe abdominal pain, vomiting, neuropathy and mental disturbances. Cutaneous porphyrias present with skin manifestations often after exposure to sun due to the accumulation of excess porphyrins near the surface of the skin.[1] Physiologically, porphyrias are classified as hepatic or erythropoietic based on the sites of accumulation of heme precursors, either in the liver or bone marrow and red blood cells.[1]

The term porphyria is derived from the Greek πορφύρα, porphyra, meaning "purple pigment". The name is likely to have been a reference to the purple discolouration of feces and urine when exposed to light in patients during an attack.[2] Although original descriptions are attributed to Hippocrates, the disease was first explained biochemically by Felix Hoppe-Seyler in 1871[3] and acute porphyrias were described by the Dutch physician Barend Stokvis in 1889.[2][4]

Signs and symptoms

Acute porphyrias

The acute, or hepatic, porphyrias primarily affect the nervous system, resulting in abdominal pain, vomiting, acute neuropathy, muscle weakness, seizures and mental disturbances, including hallucinations, depression, anxiety and paranoia. Cardiac arrhythmias and tachycardia (high heart rate) may develop as the autonomic nervous system is affected. Pain can be severe and can, in some cases, be both acute and chronic in nature. Constipation is frequently present, as the nervous system of the gut is affected, but diarrhea can also occur.

Given the many presentations and the relatively low occurrence of porphyria, the patient may initially be suspected to have other, unrelated conditions. For instance, the polyneuropathy of acute porphyria may be mistaken for Guillain-Barré syndrome, and porphyria testing is commonly recommended in those situations.[5] Systemic lupus erythematosus features photosensitivity and pain attacks and shares various other symptoms with porphyria.[6]

Not all porphyrias are genetic, and patients with liver disease who develop porphyria as a result of liver dysfunction may exhibit other signs of their condition, such as jaundice.

Patients with acute porphyria (AIP, HCP, VP) are at increased risk over their life for hepatocellular carcinoma (primary liver cancer) and may require monitoring. Other typical risk factors for liver cancer need not be present.

Cutaneous porphyrias

The cutaneous, or erythropoietic, porphyrias primarily affect the skin, causing photosensitivity (photodermatitis), blisters, necrosis of the skin and gums, itching, and swelling, and increased hair growth on areas such as the forehead. Often there is no abdominal pain, distinguishing it from other porphyrias.

In some forms of porphyria, accumulated heme precursors excreted in the urine may cause various changes in color, after exposure to sunlight, to a dark reddish or dark brown color. Even a purple hue or red urine may be seen.

Diagnosis

Porphyrin studies

Porphyria is diagnosed through biochemical analysis of blood, urine, and stool.[7] In general, urine estimation of porphobilinogen (PBG) is the first step if acute porphyria is suspected. As a result of feedback, the decreased production of heme leads to increased production of precursors, PBG being one of the first substances in the porphyrin synthesis pathway.[8] In nearly all cases of acute porphyria syndromes, urinary PBG is markedly elevated except for the very rare ALA dehydratase deficiency or in patients with symptoms due to hereditary tyrosinemia type I. [citation needed] In cases of mercury- or arsenic poisoning-induced porphyria, other changes in porphyrin profiles appear, most notably elevations of uroporphyrins I & III, coproporphyrins I & III and pre-coproporphyrin.[9]

Repeat testing during an attack and subsequent attacks may be necessary in order to detect a porphyria, as levels may be normal or near-normal between attacks. The urine screening test has been known to fail in the initial stages of a severe life threatening attack of acute intermittent porphyria.[citation needed]

The bulk (up to 90%) of the genetic carriers of the more common, dominantly inherited acute hepatic porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria) have been noted in DNA tests to be latent for classic symptoms and may require DNA or enzyme testing. The exception to this may be latent post-puberty genetic carriers of hereditary coproporphyria.[citation needed]

As most porphyrias are rare conditions, general hospital labs typically do not have the expertise, technology or staff time to perform porphyria testing. In general, testing involves sending samples of blood, stool and urine to a reference laboratory.[7] All samples to detect porphyrins must be handled properly. Samples should be taken during an acute attack, otherwise a false negative result may occur. Samples must be protected from light and either refrigerated or preserved.[7]

If all the porphyrin studies are negative, one has to consider pseudoporphyria. A careful medication review often will find the inciting cause of pseudoporphyria.

Additional tests

Further diagnostic tests of affected organs may be required, such as nerve conduction studies for neuropathy or an ultrasound of the liver. Basic biochemical tests may assist in identifying liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and other organ problems.

Pathogenesis

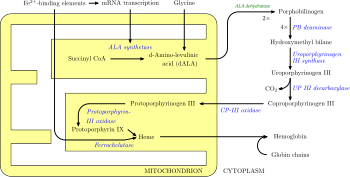

In humans, porphyrins are the main precursors of heme, an essential constituent of hemoglobin, myoglobin, catalase, peroxidase, respiratory and P450 liver cytochromes.

Deficiency in the enzymes of the porphyrin pathway leads to insufficient production of heme. Heme function plays a central role in cellular metabolism. This is not the main problem in the porphyrias; most heme synthesis enzymes—even dysfunctional enzymes—have enough residual activity to assist in heme biosynthesis. The principal problem in these deficiencies is the accumulation of porphyrins, the heme precursors, which are toxic to tissue in high concentrations. The chemical properties of these intermediates determine the location of accumulation, whether they induce photosensitivity, and whether the intermediate is excreted (in the urine or feces).

There are eight enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway, four of which—the first one and the last three—are in the mitochondria, while the other four are in the cytosol. Defects in any of these can lead to some form of porphyria.

The hepatic porphyrias are characterized by acute neurological attacks (seizures, psychosis, extreme back and abdominal pain and an acute polyneuropathy), while the erythropoietic forms present with skin problems, usually a light-sensitive blistering rash and increased hair growth.

Variegate porphyria (also porphyria variegata or mixed porphyria), which results from a partial deficiency in PROTO oxidase, manifests itself with skin lesions similar to those of porphyria cutanea tarda combined with acute neurologic attacks. All other porphyrias are either skin- or nerve-predominant.

Subtypes

Subtypes of porphyrias depend on what enzyme is deficient.

Treatment

Acute porphyria

Carbohydrates and heme

Often, empirical treatment is required if the diagnostic suspicion of a porphyria is high since acute attacks can be fatal. A high-carbohydrate diet is typically recommended; in severe attacks, a glucose 10% infusion is commenced, which may aid in recovery.

Hematin (trade name Panhematin) and heme arginate (trade name NormoSang) are the drugs of choice in acute porphyria, in the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively. These drugs need to be given very early in an attack to be effective; effectiveness varies amongst individuals. They are not curative drugs but can shorten attacks and reduce the intensity of an attack. Side effects are rare but can be serious. These heme-like substances theoretically inhibit ALA synthase and hence the accumulation of toxic precursors. In the United Kingdom, supplies of NormoSang are kept at two national centers; emergency supply is available from St Thomas' Hospital, London.[17] In the United States, Lundbeck manufactures and supplies Panhematin for infusion.[18]

Heme Arginate (NormoSang) is used during crises but also in preventive treatment to avoid crises, one treatment every 10 days

Any sign of low blood sodium (hyponatremia) or weakness should be treated with the addition of hematin or heme arginate or even Tin Mesoporphyrin as these are signs of impending syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) or peripheral nervous system involvement that may be localized or severe progressing to bulbar paresis and respiratory paralysis.[citation needed]

Cimetidine has also been reported to be effective for acute porphyric crisis and possibly effective for long term prophylaxis. .[19]

Precipitating factors

If drugs or hormones have caused the attack, discontinuing the offending substances is essential. Infection is one of the top causes of attacks and requires immediate and vigorous treatment.

Symptom control

Pain is severe, frequently out of proportion to physical signs and often requires the use of opiates to reduce it to tolerable levels. Pain should be treated as early as medically possible, due to its severity. Nausea can be severe; it may respond to phenothiazine drugs but is sometimes intractable. Hot water baths/showers may lessen nausea temporarily, though caution should be used to avoid burns or falls.

Early identification

It is recommended that patients with a history of acute porphyria, and even genetic carriers, wear an alert bracelet or other identification at all times. This is in case they develop severe symptoms, or in case of accidents where there is a potential for drug exposure, and as a result they are unable to explain their condition to healthcare professionals. Some drugs are absolutely contraindicated for any patients with any porphyria.[citation needed]

Neurologic and psychiatric problems

Patients who experience frequent attacks can develop chronic neuropathic pain in extremities as well as chronic pain in the abdomen.[20] Gut dysmotility, ileus, intussusception, hypoganglionosis, encopresis in children and intestinal pseudo-obstruction have been associated with porphyrias. This is thought to be due to axonal nerve deterioration in affected areas of the nervous system and vagal nerve dysfunction.

Pain treatment with long-acting opioids, such as morphine, is often indicated, and, in cases where seizure or neuropathy is present, Gabapentin is known to improve outcome.[21]

Depression often accompanies the disease and is best dealt with by treating the offending symptoms and if needed the judicious use of anti-depressants. Some psychotropic drugs are porphyrinogenic, limiting the therapeutic scope. Other psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, depression, mania, hallucinations, delusions, confusion, catatonia, and psychosis may occur.[22]

Seizures

Seizures often accompany this disease. Most seizure medications exacerbate this condition. Treatment can be problematic: barbiturates especially must be avoided. Some benzodiazepines are safe and, when used in conjunction with newer anti-seizure medications such as gabapentin, offer a possible regime for seizure control. Gabapentin has the additional feature of aiding in the treatment of some kinds of neuropathic pain.[21]

Magnesium sulfate and bromides have also been used in porphyria seizures, however, development of status epilepticus in porphyria may not respond to magnesium alone. The addition of hematin or heme arginate has been used during status epilepticus.[citation needed]

Underlying liver disease

Some liver diseases may cause porphyria even in the absence of genetic predisposition. These include hemochromatosis and hepatitis C. Treatment of iron overload may be required.

Hormone treatment

Hormonal fluctuations that contribute to cyclical attacks in women have been treated with oral contraceptives and luteinizing hormones to shut down menstrual cycles. However, oral contraceptives have also triggered photosensitivity and withdrawal of oral contraceptives has triggered attacks. Androgens and fertility hormones have also triggered attacks.

Erythropoietic porphyrias

These are associated with accumulation of porphyrins in erythrocytes and are rare. The rarest is Congenital erythropoetic porphyria (C.E.P) otherwise known as Gunther's disease. The signs may present from birth and include severe photosensitivity, brown teeth that fluoresce in ultraviolet light due to deposition of type one porphyrins and later hypertrichosis. Hemolytic anemia usually develops. Pharmaceutical-grade beta carotene may be used in its treatment.[23] A bone marrow transplant has also been successful in curing CEP in a few cases, although long term results are not yet available.[24]

The pain, burning, swelling and itching that occur in erythropoietic porphyrias generally require avoidance of bright sunlight. Most kinds of sunscreen are not effective, but SPF-rated long-sleeve shirts, hats, bandanas and gloves can help. Chloroquine may be used to increase porphyrin secretion in some EPs.[7] Blood transfusion is occasionally used to suppress innate heme production.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of all types of porphyria taken together has been estimated to be approximately 1 in 25,000 in the United States.[25] The worldwide prevalence has been estimated to be somewhere between 1 in 500 to 1 in 50,000 people.[26]

Culture and history

Porphyrias have been detected in all races, multiple ethnic groups on every continent including Africans, Asians, Australian aborigines, Caucasians, Peruvian, Mexican, Native Americans, and Sami. There are high incidence reports of AIP in areas of India and Scandinavia and over 200 genetic variants of AIP, some of which are specific to families, although some strains have proven to be repeated mutations.

The links between porphyrias and mental illness have been noted for decades. In the early 1950s patients with porphyrias (occasionally referred to as "Porphyric Hemophilia"[27]) and severe symptoms of depression or catatonia were treated with electroshock.

Vampires and werewolves

Porphyria has been suggested as an explanation for the origin of vampire and werewolf legends, based upon certain perceived similarities between the condition and the folklore.

In January 1964, L. Illis' 1963 paper, "On Porphyria and the Aetiology of Werwolves", was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Later, Nancy Garden argued for a connection between porphyria and the vampire belief in her 1973 book, Vampires. In 1985, biochemist David Dolphin's paper for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, "Porphyria, Vampires, and Werewolves: The Aetiology of European Metamorphosis Legends", gained widespread media coverage, thus popularizing the idea.

The theory has been rejected by a few folklorists and researchers as not accurately describing the characteristics of the original werewolf and vampire legends or the disease and for potentially stigmatizing sufferers of porphyria.[28][29]

Notable cases

The mental illness exhibited by King George III evidenced in the regency crisis of 1788 has inspired several attempts at retrospective diagnosis. The first, written in 1855, thirty-five years after his death, concluded he suffered from acute mania. M. Guttmacher, in 1941, suggested manic-depressive psychosis as a more likely diagnosis. The first suggestion that a physical illness was the cause of King George's mental derangements came in 1966, in a paper "The Insanity of King George III: A Classic Case of Porphyria",[30] with a follow-up in 1968, "Porphyria in the Royal Houses of Stuart, Hanover and Prussia".[31] The papers, by a mother/son psychiatrist team, were written as though the case for porphyria had been proven, but the response demonstrated that many, including those more intimately familiar with actual manifestations of porphyria, were unconvinced. Many psychiatrists disagreed with Hunter's diagnosis, suggesting bipolar disorder as far more probable. The theory is treated in Purple Secret,[32] which documents the ultimately unsuccessful search for genetic evidence of porphyria in the remains of royals suspected to suffer from it.[33] In 2005 it was suggested that arsenic (which is known to be porphyrogenic) given to George III with antimony may have caused his porphyria.[34] Despite the lack of direct evidence, the notion that George III (and other members of the royal family) suffered from porphyria has achieved such popularity that many forget that it is merely a hypothesis. In 2010 an exhaustive analysis of historical records concluded that the porphyria claim was based on spurious and selective interpretation of contemporary medical and historical sources.[35]

The mental illness of George III is the basis of the plot in The Madness of King George, a 1994 British film based upon the 1991 Alan Bennett play, The Madness of George III. The closing credits of the film include the comment that the illness suffered by King George has been attributed to porphyria and that it is hereditary. Among other descendants of George III theorised by the authors of Purple Secret to have suffered from porphyria (based upon analysis of their extensive and detailed medical correspondence) were his great-great-granddaughter Princess Charlotte of Prussia (Emperor William II's eldest sister) and her daughter Princess Feodora of Saxe-Meiningen. They had more success in being able to uncover reliable evidence that George III's great-great-great-grandson Prince William of Gloucester was reliably diagnosed with variegate porphyria.[36]

It is believed that Mary, Queen of Scots – King George III's great-great-great-great-great-grandmother – also suffered from acute intermittent porphyria,[37] although this is subject to much debate. It is assumed she inherited the disorder, if indeed she had it, from her father, James V of Scotland; both father and daughter endured well-documented attacks that could fall within the constellation of symptoms of porphyria.

Vlad III was also said to have suffered from acute porphyria, which may have started the notion that vampires were allergic to sunlight.[38]

Other commentators have suggested that Vincent van Gogh may have suffered from acute intermittent porphyria.[39] It has also been speculated that King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon suffered from some form of porphyria (cf. Daniel 4).[40] However, the symptoms of the various porphyrias are so extensive that a wide constellation of symptoms can be attributed to one or more of them.[citation needed]

Paula Frías Allende, the daughter of the Chilean novelist Isabel Allende, fell into a porphyria-induced coma in 1991,[41] which inspired Isabel to write the biographical book Paula, dedicated to her.

References

- ^ a b Lourenço, Charles Marquez; Lee, Chul; Anderson, Karl E. (2012). "Disorders of Haem Biosynthesis". In Saudubray, Jean-Marie; van den Berghe, Georges; Walter, John H. (eds.). Inborn Metabolic Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment (5th ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 521–532. ISBN 978-3-642-15719-6.

- ^ a b Nick Lane (2002-12-16). "Born to the purple: the story of porphyria". Scientific American. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Hoppe-Seyler F (1871). "Das Hämatin". Tubinger Med-Chem Untersuch. 4: 523–33.

- ^ Stokvis BJ. "Over twee zeldzame kleurstoffen in urine van zieken". Nederl Tijdschr Geneeskd (in Dutch). 2: 409–417. Reprinted in Stokvis BJ (December 1989). "Over twee zeldzame kleurstoffen in urine van zieken". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd (in Dutch). 133 (51): 2562–70. PMID 2689889.

- ^ Albers JW, Fink JK (2004). "Porphyric neuropathy". Muscle Nerve. 30 (4): 410–422. doi:10.1002/mus.20137. PMID 15372536.

- ^ Roelandts R (2000). "The diagnosis of photosensitivity". Arch Dermatol. 136 (9): 1152–1157. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.9.1152. PMID 10987875.

- ^ a b c d Thadani H, Deacon A, Peters T (2000). "Diagnosis and management of porphyria". BMJ. 320 (7250): 1647–1651. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7250.1647. PMC 1127427. PMID 10856069.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anderson KE; Bloomer JR; Bonkovsky HL; et al. (2005). "Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias". Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (6): 439–50. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-6-200503150-00010. PMID 15767622.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Woods, J.S. (1995). "Porphyrin metabolism as indicator of metal exposure and toxicity". In Goyer, R.A. & Cherian, M.G. (ed.). Toxicology of metals, biochemical aspects. Vol. 115. Berlin: Springer. pp. 19–52, Chapter 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Table 18-1 in: Marks, Dawn B.; Swanson, Todd; Sandra I Kim; Marc Glucksman (2007). Biochemistry and molecular biology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-8624-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Overview of the Porphyrias at The Porphyrias Consortium (a part of NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN)) Retrieved June 2011

- ^ a b Medscape - Diseases of Tetrapyrrole Metabolism - Refsum Disease and the Hepatic Porphyrias Author: Norman C Reynolds. Chief Editor: Stephen A Berman. Updated: Mar 23, 2009

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7250.1647, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/bmj.320.7250.1647instead. - ^ a b c d e Arceci, Robert.; Hann, Ian M.; Smith, Owen P. (2006). Pediatric hematolog. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-1-4051-3400-2.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7433635, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=7433635instead. - ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=3(help) - ^ "9.8.2: Acute porphyrias". British National Formulary (BNF 57). United Kingdom: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing. March 2009. p. 549. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

- ^ American Porphyria Foundation (2010). "Panhematin for Acute Porphyria". Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/16263899/

- ^ Birgisdottir,, BT (June 2010). "[Acute abdominal pain caused by acute intermittent porphyria: a case report and review of the literature.]". Laeknabladid: Journal of the Icelandic Medical Association. 96 (6): 413–418.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Tsao, YC (June 2010). "Gabapentin reduces neurovisceral pain of porphyria". Acta Neurologia Taiwanica. 19 (2): 112–115.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH. (2012) Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice. In: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 6th Edition. Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (eds.) Butterworth Heinemann. April 12, 2012. ISBN 978-1437704341

- ^ Martin A Crook.2006. Clinical chemistry and Metabolic Medicine. seventh edition. Hodder Arnold. ISBN 0-340-90616-2

- ^ Faraci M; Morreale G; Boeri E; et al. (2008). "Unrelated HSCT in an adolescent affected by congenital erythropoietic porphyria". Pediatr Transplant. 12 (1): 117–120. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00842.x. PMID 18186900.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ eMedicine > Porphyria, Cutaneous Authors: Vikramjit S Kanwar, Thomas G DeLoughery, Richard E Frye and Darius J Adams. Updated: Jul 27, 2010

- ^ Genetics Home Reference > Porphyria Reviewed July 2009

- ^ Denver, Joness. "An Encyclopaedia of Obscure Medicine". Published by University Books, Inc., 1959.

- ^ American Vampires: Fans, Victims, Practitioners, Norine Dresser, W. W. Norton & Company, 1989.

- ^ "Did vampires suffer from the disease porphyria — or not?" The Straight Dope, May 7, 1999,

- ^ Macalpine I, Hunter R (January 1966). "The "insanity" of King George 3d: a classic case of porphyria". Br Med J. 1 (5479): 65–71. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5479.65. PMC 1843211. PMID 5323262.

- ^ Macalpine I, Hunter R, Rimington C (January 1968). "Porphyria in the royal houses of Stuart, Hanover, and Prussia. A follow-up study of George 3d's illness". Br Med J. 1 (5583): 7–18. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5583.7. PMC 1984936. PMID 4866084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Warren, Martin; Rh̲l, John C. G.; Hunt, David C. (1998). Purple secret: genes, "madness" and the Royal houses of Europe. London: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-593-04148-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The authors demonstrated a single point mutation in the PPOX gene, but not one which has been associated with disease.

- ^ Cox TM, Jack N, Lofthouse S, Watling J, Haines J, Warren MJ (2005). "King George III and porphyria: an elemental hypothesis and investigation". The Lancet. 366 (9482): 332–335. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66991-7. PMID 16039338.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peters TJ, Wilkinson D (2010). "King George III and porphyria: a clinical re-examination of the historical evidence". History of Psychiatry. 21 (81 Pt 1): 3–19. doi:10.1177/0957154X09102616. PMID 21877427.

- ^ Smith, Martin (2009-12-21). "Tetrapyrroles: Birth, Life and Death". ISBN 9780387785189.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); More than one of|author1=and|last=specified (help) - ^ http://www.sussex.ac.uk/internal/bulletin/archive/25jun99/article1.html

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/208045.stm

- ^ Loftus LS, Arnold WN (1991). "Vincent van Gogh's illness: acute intermittent porphyria?". BMJ. 303 (6817): 1589–1591. doi:10.1136/bmj.303.6817.1589. PMC 1676250. PMID 1773180.

- ^ Beveridge A (2003). "The madness of politics". J R Soc Med. 96 (12): 602–604. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.12.602. PMC 539664. PMID 14645615.

- ^ Allende, Isabel (1995). Paula. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-017253-3.