Peafowl

| Peafowl, Peacock | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male Indian Peacock on display. The elongated upper tail coverts make up the train of the Indian peacock. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species | |

Peafowl are two Asiatic and one African species of flying bird in the genus Pavo of the pheasant family, Phasianidae, best known for the male's extravagant eye-spotted tail covert feathers, which it displays as part of courtship. The male is called a peacock, the female a peahen, and the offspring peachicks.[1] The adult female peafowl is grey and/or brown. Peachicks can be between yellow and a tawny colour with darker brown patches or light tan and ivory, also referred to as "dirty white". The term also embraces the Congo Peafowl, which is placed in a separate genus Afropavo.

In common with other members of the Galliformes, males possess metatarsal spurs or "thorns" used primarily during intraspecific fights.

White peacocks are not albinos; they have a genetic mutation that is known as Leucism, which causes the lack of pigments in the plumage. Albino animals and birds have a complete lack of color and red or pink eyes while White peafowl have blue eyes. The white color appears in other domestically bred peafowl but in different quantities. Chicks are born yellow and become white as they mature, according to the Peafowl Varieties Database. Indian peafowl of all colors, including white, have pink skin.

The species are:

- Congo Peafowl Afropavo congensis.

- Green Peafowl, Pavo muticus. Breeds from Burma east to Java. The IUCN lists the Green Peafowl as endangered due to hunting and a reduction in extent and quality of habitat. It is a national symbol in the history of Burma.

- Indian Peafowl, Pavo cristatus, a resident breeder in South Asia. The peacock is designated as the national bird of India.

Plumage

The male (peacock) Indian Peafowl has iridescent blue-green or green colored plumage. The peacock tail ("train") is not the tail quill feathers but the highly elongated upper tail covert feathers. The "eyes" are best seen when the peacock fans its tail. Both species have a crest atop the head. The female (peahen) Indian Peafowl has a mixture of dull green, brown, and grey in her plumage. Although she lacks the long upper tail coverts of the male, she has a crest. The female also displays her plumage to ward off female competition or signal danger to her young.

The Green Peafowl appears different from the Indian Peafowl. The male has a green and gold plumage as well as an erect crest. The wings are black with a sheen of blue. Unlike the Indian Peafowl, the Green Peahen is similar to the male, only having shorter upper tail coverts and less iridescence.

Coloration

As with many birds, vibrant iridescent plumage colours are not primarily pigments, but structural colouration. Optical interference Bragg reflections, based on regular, periodic nanostructures of the barbules (fiber-like components) of the feathers produce the peacock's colors. Slight changes to the spacing result in different colours. Brown feathers are a mixture of red and blue: one colour is created by the periodic structure, and the other is a created by a Fabry–Pérot interference peak from reflections from the outer and inner boundaries. Such structural colouration causes the iridescence of the peacock's hues since, unlike pigments, interference effects depend on light angle.

Colour mutations exist through selective breeding, such as the White Peafowl and the Black-Shouldered Peafowl.

Evolution and sexual selection

Charles Darwin first theorized in On the Origin of Species that the peacock's plumage had evolved through sexual selection. This idea was expanded upon in his second book, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex.

The sexual struggle is of two kinds; in the one it is between individuals of the same sex, generally the males, in order to drive away or kill their rivals, the females remaining passive; whilst in the other, the struggle is likewise between the individuals of the same sex, in order to excite or charm those of the opposite sex, generally the females, which no longer remain passive, but select the more agreeable partners.[2]

Work concerning female behavior in many species of animals has sought to confirm Darwin's basic idea of female preference for males with certain characteristics as a major force in the evolution of species.[3] Females have often been shown to distinguish small differences among potential mates and to prefer mating with individuals bearing the most exaggerated characters.[4] In some cases, those males have been shown to be more healthy and vigorous, suggesting that the ornaments serve as markers indicating the males' abilities to survive and, thus, their genetic qualities.

The peacock is perhaps the best-known example of traits believed to have arisen through sexual selection, though in recent years this theory has become the object of some controversy.[5] It is known that male peafowl erect their trains to form a shimmering fan in their display to females. Marion Petrie tested whether or not these displays signaled a male's genetic quality by studying a feral population of peafowl in Whipsnade Wildlife Park in southern England. She showed that the number of eyespots in the train predicted a male's mating success, and this success could be manipulated by cutting the eyespots off some of the male's tails.[6] Females lost interest in pruned males and became attracted to untrimmed ones. Further testing revealed that males with fewer eyespots, and thus with lower mating success, were more likely to suffer from greater predation.[7] Even more interestingly, she allowed females to mate with males that had variable numbers of eyespots and reared the offspring in a communal incubator to control for differences in maternal care. Chicks fathered by more ornamented males weighed more than those fathered by less ornamented males, an attribute generally associated with better survival rate in birds. When these chicks were released into the park and recaptured one year later, those with heavily ornamented fathers were found to be better able to avoid predators and survive in natural conditions.[3] Thus, Petrie's work has shown correlations between tail ornamentation, mating success and increased survival ability in both the ornamented males and their offspring.

Furthermore, peafowl and their sexual characteristics have been used in the discussion of the causes for sexual traits. Amotz Zahavi used the excessive tail plumes of male peafowls as evidence for his “Handicap Principle”.[8] Considering that these trains are obviously deleterious to the survival of an individual (due to the more brilliant plumes being highly visible to predators and the longer plumes making escape from danger more difficult), Zahavi argued that only the most fit males could survive the handicap of a large tail. Thus, the brilliant tail of the peacock serves as an indicator for females that highly ornamented males are good at surviving for other reasons, and are, therefore, more preferable mates. This theory may be contrasted with Fisher's theory that male sexual traits, such as the peacock's train, are the result of selection for attractive traits because these traits are considered attractive.

However, some disagreement has arisen in recent years concerning whether or not female peafowl do indeed select males with more ornamented trains. In contrast to Petrie's findings, a seven-year Japanese study of free-ranging peafowl came to the conclusion that female peafowl do not select mates solely on the basis of their trains. Mariko Takahashi found no evidence that peahens expressed any preference for peacocks with more elaborate trains (such as trains having more ocelli), a more symmetrical arrangement, or a greater length.[9] Takahashi determined that the peacock's train was not the universal target of female mate choice, showed little variance across male populations, and, based on physiological data collected from this group of peafowl, do not correlate to male physical conditions. Adeline Loyau and her colleagues responded to Takahashi's study by voicing concern that alternative explanations for these results had been overlooked, and that these might be essential for the understanding of the complexity of mate choice.[10] They concluded that female choice might indeed vary in different ecological conditions.

It has been also suggested that peacocks' display of colorful and oversize trains with plenty of eyespots, together with their extremely loud call and fearless behavior, have been formed by the forces of natural selection (not sexual selection), and served as an aposematic warning display to intimidate predators and rivals. [11]

Behavior

Peafowl are forest birds that nest on the ground but roost in trees. They are terrestrial feeders. All species of peafowl are believed to be polygamous. However, it has been suggested that peahens entering a green peacock's territory are really his own juvenile or sub-adult young and that green peafowl are really monogamous in the wild.[citation needed]

Diet

Peafowl are omnivorous and eat most plant parts, flower petals, seed heads, insects and other arthropods, reptiles, and amphibians.

Cultural significance

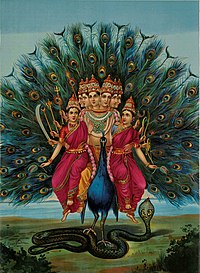

In Hindu culture, the peacock is the mount of the lord Karthikeya, the god of war. A demon king, Surapadman, was split into two by Karthikeya and the merciful lord converted the two parts as an integral part of himself, one becoming a peacock (his mount) and another a rooster adorning his flag. The peacock displays the divine shape of Omkara when it spreads its magnificent plumes into a full-blown circular form.[12]

Even though the Peafowl is native to India, in Babylonia and Persia the Peacock is seen as a guardian to royalty, and is often seen in engravings upon the thrones of royalty. The monarchy in Iran is referred to as the Peacock Throne. Melek Taus (ملك طاووس—Kurdish Tawûsê Melek), the "Peacock Angel", is the Yazidi name for the central figure of their faith. The Yazidi consider Tawûsê Melek an emanation of God and a benevolent angel who has redeemed himself from his fall and has become a demiurge who created the cosmos from the Cosmic egg. After he repented, he wept for 7,000 years, his tears filling seven jars, which then quenched the fires of hell. In art and sculpture, Tawûsê Melek is depicted as a peacock. However, peacocks are not native to the lands where Tawûsê Melek is worshipped.[citation needed]

In Islamic tradition the peacock is often viewed as allied with Satan. Satan or Iblis was known as a peacock of angels and Islamic tradition cites that the peacock aided Iblis in Paradise. In Sufism Satan is also metaphorically seen as peacock while the simurgh is a metaphor for God. The Yazidi central figure is often seen as the devil in Islam which has led to a dogmatic conflict between both faiths. Melek Taus is also known as shaytan or the devil in Islam.[citation needed]

In Hellenistic imagery, the Greek goddess Hera's chariot was pulled by peacocks, birds not known to Greeks before the conquests of Alexander. Alexander's tutor, Aristotle, refers to it as "the Persian bird." The peacock motif was revived in the Renaissance iconography that unified Hera and Juno, and which European painters focused on.[13] One myth states that Hera's servant, the hundred-eyed Argus Panoptes, was instructed to guard the woman-turned-cow, Io. Hera had transformed Io into a cow after learning of Zeus's interest in her. Zeus had the messenger of the gods, Hermes, kill Argus through eternal sleep and free Io. According to Ovid, to commemorate her faithful watchman, Hera had the hundred eyes of Argus preserved forever, in the peacock's tail.[14]

In 1956, John J. Graham created an abstraction of an eleven-feathered peacock logo for American broadcaster NBC. This brightly hued peacock was adopted due to the increase in colour programming. NBC's first colour broadcasts showed only a still frame of the colourful peacock. The emblem made its first on-air appearance on May 22, 1956.[15] NBC later adopted the slogan "We're proud as a peacock!" The current version of the logo debuted in 1986 and has six feathers (yellow, orange, red, purple, blue, green). A stylized peacock in full display is the logo for the Pakistan Television Corporation.

In some cultures the peacock is also a symbol of pride or vanity, due to the way the bird struts and shows off its plumage.

Gastronomy

During the Medieval period, various types of fowl were consumed as food, with the poorer populations (such as serfs) consuming more common birds, such as chicken.[citation needed] However, the more wealthy gentry were privileged to more exotic foods, such as swan,[citation needed] and even peafowl were consumed. On a king's table, a peacock would be for ostentatious display as much as for culinary consumption.[16]

Peafowl is generally considered poultry, even though neither its meat nor its eggs are frequently eaten. It is considered poultry due to the possibility that the meat and eggs can be eaten and that the species is often raised for its feathers.[citation needed]

References

- ^ "Peacock (bird)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ Darwin, Charles. (1871), The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex John Murray, London.

- ^ a b Zuk, Marlene. (2002). Sexual Selections: What we can and can't learn about sex from animals. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA.

- ^ Davies N, Krebs J, and West S. (2012). An Introduction to Behavioral Ecology, 4th Ed. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford.

- ^ Male Peacock's Feather Fails to Impress Females: Study". Thaindian News. March 27, 2008.

- ^ Petrie et al. (1991). Anim. Behav., 41,;323-331.

- ^ Petrie et al. (1991). Anim . Behav., 44; 585 –586.

- ^ Zahavi, A. (1975). Journal of Theoretical Biology, 53: 205-214.

- ^ Takahashi M et al. (2008). Anim . Behav., 75: 1209-1219.

- ^ Loyau A et al. (2008). Anim . Behav., 76; e5-e9.

- ^ Joseph Jordania Why do People Sing? Music in Human Evolution Logos, 2011. Chapter: Peacock's Tail: Tale of Beauty and Intimidation pg.192-196

- ^ Ayyar, SRS. "Muruga -- The Ever-Merciful Lord". Murugan Bhakti: The Skanda Kumāra site. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Seznec, Jean, The Survival of the Pagan Gods : Mythological Tradition in Renaissance Humanism and Art, 1953

- ^ Ovid I, 625. The peacock is an Eastern bird, unknown to Greeks before the time of Alexander.

- ^ Brown, Les (1977). The New York Times Encyclopedia of Television. Times Books. p. 328. ISBN 0-8129-0721-3.

- ^ "Fowl Recipes". Medieval-Recipes.com. 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

External links

- Peafowl Varieties Database

- Etymology of the word Peacock

- United Peafowl Association Knowledge Base

- Peafowl videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection.

- Behavioural Ecologists Elucidated How Peahens Choose Their Mates, And Why, an article at Science Daily.