Newgate Prison

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777. The prison was extended and rebuilt many times, and remained in use for over 700 years, from 1188 to 1902.

Early history

The first prison at Newgate was built in 1188 on the orders of Henry II. It was significantly enlarged in 1236, and the executors of Lord Mayor Dick Whittington were granted a license to renovate the prison in 1422. The prison was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, and was rebuilt in 1672, extending into new buildings on the south side of the street.

According to medieval statute, the prison was to be managed by two annually elected Sheriffs, who in turn would sublet the administration of the prison to private "gaolers", or "Keepers", for a price. These Keepers in turn were permitted to exact payment directly from the inmates, making the position one of the most profitable in London. Inevitably, the system offered incentives for the Keepers to exhibit cruelty to the prisoners, charging them for everything from entering the gaol to having their chains both put on and taken off. Among the most notorious Keepers in the Middle Ages were the 14th-century gaolers Edmund Lorimer, who was infamous for charging inmates four times the legal limit for the removal of irons, and Hugh De Croydon, who was eventually convicted of blackmailing prisoners in his care.

Over the centuries, Newgate was used for a number of purposes including imprisoning people awaiting execution, although it was not always secure: burglar Jack Sheppard escaped from the prison two times before he went to the gallows at Tyburn in 1724. Prison chaplain Paul Lorrain achieved some fame in the early 18th century for his sometimes dubious publication of Confessions of the condemned.

Rebuilding

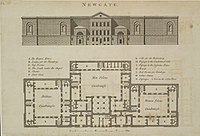

Parliament having granted £50,000 towards the cost, the City of London provided a piece of ground 1,600 feet (500 m) long and 50 feet (15 m) deep to enlarge the site of the prison and to build a new sessions house. The work was begun in 1770 to the designs of George Dance. The new prison was almost finished when it was stormed by a mob during the Gordon riots in June 1780. The building was gutted by fire, and the walls badly damaged. The cost of repairs was estimated at £30,000. Dance’s new prison was finally completed in 1782.[1]

The new prison was constructed to an architecture terrible design intended to discourage law-breaking. The building was laid out around a central courtyard, and was divided into two sections: a "Common" area for poor prisoners and a "State area" for those able to afford more comfortable accommodation. Each section was further sub-divided to accommodate felons and debtors.

Executions

In 1783, the site of London's gallows was moved from Tyburn to Newgate. Public executions outside the prison – by this time, London's main prison – continued to draw large crowds. It was also possible to visit the prison by obtaining a permit from the Lord Mayor of the City of London or a sheriff. The condemned were kept in narrow sombre cells separated from Newgate Street by a thick wall and receiving only a dim light from the inner courtyard. The gallows were constructed outside a window in Newgate Street. Until the 20th century, future British executioners were trained at Newgate; one of the last was John Ellis in 1901.

During the early 19th century the prison attracted the attention of the social reformer Elizabeth Fry. She was particularly concerned at the conditions in which female prisoners (and their children) were held. After she presented evidence to the House of Commons improvements were made. In 1858, the interior was rebuilt with individual cells.

From 1868, public executions were discontinued and executions were carried out on gallows inside Newgate. Michael Barrett was the last man to be hanged in public outside Newgate Prison (and the last person to be publicly executed in Great Britain) on 26 May 1868. In total (publicly or otherwise), 1,169 people were executed at the prison.[2]

Demolition

The prison closed in 1902, and was demolished in 1904. The Central Criminal Court (also known as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands) now stands upon its site.

The original door from a prison cell used to house St. Oliver Plunkett in 1681 is on display at St. Peter's Church in Drogheda, Ireland. The original iron gate leading to the gallows was used for decades in an alleyway in Buffalo, New York and is currently housed in that city at Canisius College.

Famous prisoners

Other famous prisoners at Newgate include:

- John Bradford (1510–1555), religious reformer.

- Thomas Bambridge, former warden of Fleet Prison

- John Cooke – English Prosecutor of Charles I, regicide executed in 1660

- Giacomo Casanova – Venetian Libertine, imprisoned for alleged bigamy

- William Chaloner – Currency counterfeiter and con artist

- William Cobbett – Parliamentary reformer and agrarian

- John Frith – Protestant priest and martyr

- Thomas Neill Cream – prominent doctor who was tried and convicted for poisoning several of his patients, claimed to be notorious serial killer Jack the Ripper while on the gallows.

- Daniel Defoe – author of Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders (whose protagonist is born and imprisoned in Newgate Prison)

- Daniel Eaton, who was the subject of the defense Percy Bysshe Shelley offered in his famous essay, A Letter to Lord Ellenborough.

- Lord George Gordon – UK politician whom the Gordon Riots are named after

- Ben Jonson – playwright and poet, imprisoned for the 22 September 1598 killing of his fellow actor Gabriel Spenser in a duel. Freed by pleading benefit of clergy.

- Jørgen Jørgensen - a Danish adventurer who helped build the first settlement in Tasmania and for a short time in 1809 ruled over Iceland, after which he became a British spy and was later deported to Tasmania.

- William Kidd – the infamous pirate and privateer - known as Captain Kidd - was taken to Execution Dock at Wapping and hanged in 1701.

- John Law – economist

- Thomas Lloyd (stenographer) – first stenographer of the U.S. Congress

- James MacLaine – aka "the Gentleman Highwayman" – notorious robber

- Sir Thomas Malory – highwayman, possible author of Le Morte d'Arthur, a saga about King Arthur

- Catherine Murphy, an English counterfeiter who became the last woman to be officially executed by burning in England and Great Britain in 1789.

- Titus Oates – anti-Catholic conspirator

- William Penn – the Quaker who founded the state of Pennsylvania

- Miles Prance – alleged witness to the murder of Edmund Berry Godfrey

- Jack Sheppard – thief, escapee

- Ikey Solomon – successful and infamous fence of the late 18th and early 19th centuries

- John Bellingham – assassin

- Robert Southwell – English Jesuit priest, poet and martyr who was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn in 1595.

- Owen Suffolk – Australian bush-ranger

- Jane Voss (alias Jane Roberts) a highwaywoman and thief who was executed in 1684.

- Ellis Casper, who helped to perpetrate the 1839 Gold Dust Robbery held in Newgate before being transported to Van Diemen's Land in 1841.

- Mary Wade – Youngest female convict transported to Australia

- Edward Gibbon Wakefield – British politician, the driving force behind much of the early colonization of South Australia, and later New Zealand

- Joseph Wall, a colonial administrator who was hanged for having a British soldier flogged to death.

- John Walter Sr. – Founder of The Times, for libel on the Duke of York

- Catherine Wilson – nurse and suspected serial killer. Last woman hanged publicly in London[3]

In literature

- A record of executions conducted at the prison, together with commentary, was published as The Newgate Calendar, which inspired a genre of Victorian literature known as the Newgate novel.

- The prison appears in a number of novels by Charles Dickens, including Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty and Great Expectations, and is the subject of an entire essay in his work Sketches by Boz.

- The prison is also depicted in:

- Geoffrey Chaucer's anthology The Canterbury Tales (The Cook's Tale)

- Daniel Defoe's novel Moll Flanders

- William Godwin's novel Caleb Williams

- Michael Crichton's novel The Great Train Robbery

- Neal Stephenson's Baroque Cycle

- Leon Garfield's novel Smith

- Joseph O'Connor's novel Star of the Sea – where one section concerns a character's imprisonment and subsequent escape from Newgate.

- Louis L'Amour's novel To The Far Blue Mountains – where the main character Barnabas Sackett is first imprisoned and later escapes from Newgate.

- Bernard Cornwell's novel Gallows Thief

- David Liss's novel A Conspiracy of Paper and the sequel, A Spectacle of Corruption

- John Gay's Ballad Opera The Beggar's Opera

- Richard Zacks's novel The Pirate Hunter (The True Story of Captain Kidd)

- Wachowski brothers' film V For Vendetta

- George MacDonald Fraser's novel Flashman's Lady

- Jonathan Barnes' The Somnambulist

- Marguerite Henry's novel King of the Wind

- C J Sansom's novel Dark Fire

- Jackie French's novel Tom Appleby Convict Boy

- Coventry Patmore's poem A London Fete

- James Norman Hall and Charles Nordhoff's novel Botany Bay

- Kathleen Winsor's novel Forever Amber

- Donald Thomas's short story "The Execution of Sherlock Holmes".

- Robert McCammon's novel Speaks the Nightbird Volume 2: Evil Unveiled

- T.C. Boyle's novel Water Music

- Erica Jong's novel Fanny: Being the True History of the Adventures of Fanny Hackabout-Jones

- Rachel Florence Roberts's novel The Medea Complex

References

Notes

- ^ Britton, John; Pugin, A. (1828). Illustrations of the Public Buildings of London: With Historical and Descriptive Accounts of each Edifice. Vol. 2. London. pp. 102 et seq.

- ^ History of Criminal Justice. Elsevier. 2011-07-22. ISBN 9781437734911. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Murder UK

Further reading

- Halliday, Stephen (2007), Newgate: London's Prototype of Hell, The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7509-3896-9