Jung Chang

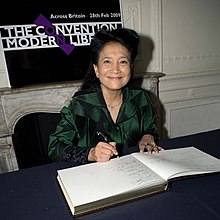

Jung Chang | |

|---|---|

in London (January 2010) | |

| Born | 25 March 1952 Yibin, Sichuan, China |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | British citizen [1] |

| Period | 1986–present |

| Genre | Biography |

| Subject | China |

| Spouse | Jon Halliday |

Jung Chang (simplified Chinese: 张戎; traditional Chinese: 張戎; pinyin: Zhāng Róng; Wade–Giles: Chang Jung, Mandarin pronunciation: [tʂɑ́ŋ ɻʊ̌ŋ], born March 25, 1952) is a Chinese-born British writer now living in London, best known for her family autobiography Wild Swans, selling over 10 million copies worldwide but banned in the People's Republic of China.

Her 832-page biography of Mao Zedong, Mao: The Unknown Story, written with her husband, the British historian Jon Halliday, was published in June 2005.

Life in China

Chang was born March 25, 1952 in Yibin, Sichuan Province, China. Her parents were both Communist Party of China officials, and her father was greatly interested in literature. As a child she quickly developed a love of reading and writing, which included composing poetry.

As Party cadres, life was relatively good for her family at first; her parents worked hard, and her father became successful as a propagandist at a regional level. His formal ranking was as a "level 10 official", meaning that he was one of 20,000 or so most important cadres, or ganbu, in the country. The Communist Party provided her family with a dwelling in a guarded, walled compound, a maid and chauffeur, as well as a wet-nurse and nanny for Chang and her four siblings. This level of privilege in China's relatively impoverished 1950s was extraordinary.

Chang writes that she was originally named Er-hong (二鴻 "Second Swan"), which sounds like the Chinese word for "faded red". As communists were "deep red", she asked her father to rename her when she was 12 years old, specifying she wanted "a name with a military ring to it." He suggested "Jung", which means "martial affairs."

Cultural Revolution

Like many of her peers, Chang chose to become a Red Guard at the age of 14, during the early years of the Cultural Revolution. In Wild Swans she said she was "keen to do so", "thrilled by my red armband".[3] In her memoirs, Chang states that she refused to participate in the attacks on her teachers and other Chinese, and she left after a short period as she found the Red Guards too violent.

The failures of the Great Leap Forward had led her parents to oppose Mao Zedong's policies. They were targeted during the Cultural Revolution, as most high-ranking officials were. When Chang's father criticized Mao by name, Chang writes in Wild Swans that this exposed them to retaliation from Mao's supporters. Her parents were publicly humiliated — ink was poured over their heads, they were forced to wear placards denouncing them around their necks, kneel in gravel and to stand outside in the rain — followed by imprisonment, her father's treatment leading to lasting physical and mental illness. Their careers were destroyed, and her family was forced to leave their home.

Before her parents' denunciation and imprisonment, Chang had unquestioningly supported Mao and criticized herself for any momentary doubts.[4] But by the time of his death, her respect for Mao, she writes, had been destroyed. Chang wrote that when she heard he had died, she had to bury her head in the shoulder of another student to pretend she was grieving. She explained her change on the stance of Mao with the following comments:

The Chinese seemed to be mourning Mao in a heartfelt fashion. But I wondered how many of their tears were genuine. People had practiced acting to such a degree that they confused it with their true feelings. Weeping for Mao was perhaps just another programmed act in their programmed lives.[5]

Chang's depiction of the Chinese people as having been "programmed" by Maoism would ring forth in her subsequent writings.

Studying English

The disruption of the university system by the Red Guards led Chang, like most of her generation, away from the political maelstroms of the academy. Instead, she spent several years as a peasant, a barefoot doctor (a part-time peasant doctor), a steelworker and an electrician, though she received no formal training because of Mao's policy, which did not require formal instruction as a prerequisite for such work.

The universities were eventually re-opened and she gained a place at Sichuan University to study English, later becoming an assistant lecturer there. After Mao's death, she passed an exam which allowed her to study in the West, and her application to leave China was approved once her father was politically rehabilitated.

Life in Britain

Academic background

Chang left China in 1978 to study in Britain on a government scholarship, staying first in Soho, London. She later moved to Yorkshire, studying linguistics at the University of York with a scholarship from the university itself, living in Derwent College. She received her Ph.D. in linguistics from York in 1982, becoming the first person from the People's Republic of China to be awarded a Ph.D. from a British university. In 1986, she and Jon Halliday published Mme Sun Yat-sen (Soong Ching-ling), a biography of Sun Yat-Sen's widow.

She has also been awarded honorary doctorates from the University of Buckingham, the University of York, the University of Warwick, and the Open University. She lectured for some time at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, before retiring in the 1990s to concentrate on her writing.

New experiences

In 2003, Jung Chang wrote a new foreword to Wild Swans, describing her early life in Britain and explaining why she wrote the book. Having lived in China during the 1960s and 1970s, she found Britain exciting. After the initial culture-shock, she soon grew to love the country, especially its diverse range of culture, literature and arts. She found even colourful window-boxes worth writing home about - Hyde Park and the Kew Gardens were inspiring. She took every opportunity to watch Shakespeare's plays in both London and York. However she still has a special place for China in her heart, saying in an interview with HarperCollins, "I feel perhaps my heart is still in China".[6]

Chang lives in west London with her husband, the British historian Jon Halliday, who specializes in Soviet history. She regularly visits mainland China to see her family and friends there, with permission from the Chinese authorities, despite carrying out research on her biography of Mao there.

Celebrity

The publication of Jung Chang's second book Wild Swans made her a celebrity. Chang's unique style, using a personal description of the life of three generations of Chinese women to highlight the many changes that the country went through, proved to be highly successful. Large numbers of sales were generated, and the book's popularity led to its being sold around the world and translated into several languages.

Chang became a popular figure for talks about Communist China; and she has travelled across Britain, Europe, America, and many other places in the world. She returned to the University of York on June 14, 2005, to address the university's debating union and spoke to an audience of over 300, most of whom were students.[7] The BBC invited her onto the panel of Question Time for a first-ever broadcast from Shanghai on 10 March 2005,[8] but she was unable to attend when she broke her leg a few days beforehand.

Publications

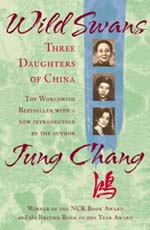

Wild Swans

The international bestseller is a biography of three generations of Chinese women in 20th century China — her grandmother, mother, and herself. Chang paints a vivid portrait of the political and military turmoil of China in this period, from the marriage of her grandmother to a warlord, to her mother's experience of Japanese-occupied Jinzhou during the Second Sino-Japanese War, and her own experience of the effects of Mao's policies of the 1950s and 1960s.

Wild Swans was translated into 30 languages and sold 10 million copies, receiving praise from authors such as J. G. Ballard. It is banned in mainland China, though two pirated versions are available, as are translations in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Mao: The Unknown Story

Chang's 2005 work, a biography of Mao, was co-authored with her husband Jon Halliday and portrays Mao in an extremely negative light. The couple travelled all over the world to research the book, which took 12 years to write.[9] They interviewed hundreds of people who had known Mao, including George Bush, Sr., Henry Kissinger, and Tenzin Gyatso, the Dalai Lama.[9]

Amongst their criticisms of Mao, Chang and Halliday argue that despite being born into a rich peasant family, he had little concern for the welfare of the Chinese peasantry. They hold Mao responsible for the famine resulting from the Great Leap Forward and claim that he exacerbated the famine by allowing the export of grain to continue when China did not have sufficient grain to feed its own people. They also claim that Mao had many political opponents arrested and murdered, including some of his personal friends, and argue that he was a more tyrannical leader than had previously been thought.

Mao: The Unknown Story became a bestseller, with UK sales alone reaching 60,000 in six months.[10] Academics and commentators wrote reviews ranging from praise[11] to criticism.[12] Professor Richard Baum said that it had to be "taken very seriously as the most thoroughly researched and richly documented piece of synthetic scholarship" on Mao.[13] On the other hand, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that while few commentators "disput[ed] the subject," "some of the world's most eminent scholars of modern Chinese history" had referred to the book as "a gross distortion of the records."[10][14]

Empress Dowager Cixi

In October 2013, Chang published a new biography of the Empress Dowager Cixi, who unofficially controlled the Manchu Qing Dynasty in China for 47 years, from 1861 to her death in 1908. Chang argues that Cixi has been "deemed either tyrannical and vicious, or hopelessly incompetent—or both", and that this view is both simplistic and inaccurate. Chang deeply admires Cixi, and portrays her as intelligent, open-minded, and a proto-feminist limited by a xenophobic and deeply conservative imperial bureaucracy. Although Cixi is often accused of reactionary conservatism (especially for her treatment of the Guangxu Emperor during and after the Hundred Days' Reform), Chang concludes that Cixi "brought medieval China into the modern age."[15] Newspaper reviews have also been positive in their assessment. Te-Ping Chen, writing in the Wall Street Journal, found the book "packed with details that bring to life its central character".[16]

The New York Times reported that a number of historians were wary of Chang's conclusions, however, because the book was so laudatory of Cixi.[17] China expert Orville Schell called Chang's new biography of Cixi "absorbing" although sometimes bordering on hagiography.[15] He had high praise for Chang's extensive use of Chinese-language sources, both primary and modern, which have rarely been used in English-language biographiers of Cixi.[15] John Delury, assistant professor of Chinese studies at Yonsei University in South Korea, also had praise for Chang's use of new Chinese-language sources. But he cautioned that the book assessed so positively nearly everything that Cixi did that the sources may not have been objectively assessed. He implied that Chang's book was neither very scholarly nor very careful in its use of sources.[17] Mass media reviewers have been similarly distrustful because of the book's overwhelmingly positive tone. James Owne in The Daily Telegraph felt Chang "airbrushed" Cixi, concluding: "One can see why she has fallen in love with her spirited subject, but the woman who ended the custom of foot-binding was capable of great cruelty and stupidity of her own. The smell of blood needs to be acknowledged, not just that of lilies."[18]

Isabel Hilton in The Guardian found Chang's praise for Cixi "a little unqualified".[19] She points out, for example, that Cixi crushed the Guangxu Emperor's Hundred Days' Reform in 1898, but then implemented many more reforms after the Boxer Rebellion. Hilton observes that Chang interprets Cixi's actions in the most positive light possible, and emblematic of Cixi's progressive views. Other historians have interpreted these actions as those of a ruler who wants to cling to power, and whose post-Boxer Rebellion policies were "grudging concessions."[19] But she applauded the book for making "a spirited, if partisan contribution" to the literature on Cixi.[19]

List of works

- Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, Madame Sun Yat-Sen: Soong Ching-Ling (London, 1986); Penguin, ISBN 0-14-008455-X

- Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (London, 1992); 2004 Harper Perennial ed. ISBN 0-00-717615-5

- Jung Chang, Lynn Pan and Henry Zhao (edited by Jessie Lim and Li Yan), Another province: new Chinese writing from London (London, 1994); Lambeth Chinese Community Association, ISBN 0-9522973-0-2.

- Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, Mao: The Unknown Story (London, 2005); Jonathan Cape, ISBN 0-679-42271-4

- Jung Chang, Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013), ISBN 0224087436

References

- ^ "Turning the page on the Asian mystique", The Jakarta Post, March 31, 2010

- ^ "Jung Chang". Woman's Hour. December 18, 2013. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (London, 2004), p. 378.

- ^ Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (London, 2004), p. 270.

- ^ Wild Swans, p. 633.

- ^ "an interview with Jung Chang". HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 2005-11-06. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Record crowd for Jung Chang, The Union - The York Union (25 June 2005)

- ^ "BBC's Question Time heads to China". Asia-Pacific Broadcasting Union. 2005-02-17. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ a b "Desert Island Discs with Jung Chang". Desert Island Discs. 2007-11-16. BBC. Radio 4.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Fenby, Jonathan (2005-12-04). "Storm rages over bestselling book on monster Mao". London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ John Walsh (2005-06-10). "Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday". Asian Review of Books. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ John Pomfret (2005-12-11). "Chairman Monster". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ Sophie Beach (2005-09-05). "CDT Bookshelf: Richard Baum recommends "Mao: The Unknown Story"". China Digital Times. Archived from the original on 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ "A swan's little book of ire". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-10-08. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- ^ a b c Schell, Orville. "Her Dynasty." New York Times. October 25, 2013. Accessed 2013-10-25.

- ^ Chen, Te-Ping."Jung Chang Rewrites Empress Cixi." Wall Street Journal. October 3, 2013. Accessed 2013-11-03.

- ^ a b Bradsher, Keith. "Another Look at the Empress Dowager Cixi, This Time as the Great Modernizer." New York Times. October 30, 2013. Accessed 2013-11-03.

- ^ Owen, James. "Empress Dowager Cixi by Jung Chang, Review." The Daily Telegraph. October 11, 2013. Accessed 2013-11-03.

- ^ a b c Hilton, Isabel. "Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China by Jung Chang – Review." The Guardian. October 25, 2013. Accessed 2013-11-03.

- 1952 births

- Living people

- Academics of SOAS, University of London

- Alumni of the University of West London

- Alumni of the University of York

- British autobiographers

- British biographers

- British historians

- Chinese emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Historians of China

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- NCR Book Award winners

- People from Yibin

- Sichuan University alumni

- Writers from London