Melanoma

| Melanoma | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

Melanoma is a malignant tumor of melanocytes and, less frequently, of retinal pigment epithelial cells (of the eye, see uveal melanoma). While it represents one of the rarer forms of skin cancer, melanoma underlies the majority of skin cancer-related deaths[1] [2]. Despite many years of intensive laboratory and clinical research, the sole effective cure is surgical resection of the primary tumor before it achieves a thickness of greater than 1 mm. Metastatic forms of the disease, where cells from the primary have moved to other parts of the body and proliferated, are extremely dangerous and patient survival rarely exceeds two years.

History

While there is little serious doubt that melanoma is not a relatively new disease, evidence for its occurrence in antiquity is scarce. However, one example lies in a 1960s examination of nine Peruvian Inca mummies, radiocarbon dated to be approximately 2400 years old, which showed apparent signs of melanoma. These signs were in the form of melanotic masses in the skin and diffuse metastases to the bones[3]

John Hunter is reported to be the first to operate on metastatic melanoma in 1787[4]. Although not knowing precisely what it was he labelled it as a "cancerous fungous excrescence". The excised tumor was preserved in the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons. It was not until 1968 that microscopic examination of the specimen revealed it to be an example of metastatic melanoma.[5]

The French physician René Laennec was the first to describe melanoma as a disease entity. His report was first presented during a lecture for the Faculté de Médecine de Paris in 1804 and then published as a bulletin in 1806.[6]

The first formal acknowledgement that advanced melanoma is untreatable comes from Samuel Cooper in 1840. He stated that the '... only chance for benefit depends upon the early removal of the disease ...'[7]. More than one and a half centuries later this situation remains largely unchanged.

Epidemiology and causes

Melanoma of the skin accounts for 160,000 new cases worldwide each year, and is slightly more frequent in women than in men. It is particularly common in white populations living in sunny climates.[8] According to the WHO Report about 48,000 deaths worldwide due to malignant melanoma are registered annually.[9]

Generally, an individuals risk for developing melanoma depends on two groups of factors: intrinsic and environmental[10].

Epidemiologic studies from Australia suggest that exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVA [11] and UVB) is one of the major contributors to the development of melanoma. This radiation causes errors in the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of cells, making them go through mitosis (cell division) at an unhealthy rate. Occasional extreme sun exposure (resulting in "sunburn") is causally related to melanoma. Those with more chronic long term exposure (outdoor workers) may develop protective mechanisms. Melanoma is most common on the back in men and on legs in women (areas of intermittent sun exposure) and is more common in indoor workers than outdoor workers (in a British study). Other factors are mutations in or total loss of tumor suppressor genes. Use of sunbeds (with deeply penetrating UVA rays) has been linked to the development of skin cancers, including melanoma.

Possible significant elements in determining risk include the intensity and duration of sun exposure, the age at which sun exposure occurs, and the degree of skin pigmentation. Exposure during childhood is a more important risk factor than exposure in adulthood. This is seen in migration studies in Australia where people tend to retain the risk profile of their country of birth if they migrate to Australia as an adult. Individuals with blistering or peeling sunburns (especially in the first twenty years of life) have a significantly greater risk for melanoma.

Fair and red-headed people are at greater risk for developing melanoma. A person with multiple atypical nevi or dysplastic nevi are at a significant risk. Persons born with giant congenital nevi are at increased risk.[12]

A family history of melanoma greatly increases a person's risk. Mutations in CDKN2A, CDK4 and several other genes have been found in melanoma-prone families.[13] Patients with a history of one melanoma are at increased risk of developing a second primary tumour. [14]

The incidence of melanoma has increased in the recent years, but it is not clear to what extent changes in behavior, in the environment, or in early detection are involved.[15]

Prevention

Primary

- Minimize exposure to sources of ultraviolet radiation (the sun and sunbeds)[16]

- Follow sun protection measures. Wearing protective clothing (long-sleeved shirts, long trousers, and broad-brimmed hats.) can offer protection. Using a sunscreen with an SPF rating of 30 or better on exposed areas has preventive effect.[17]

Secondary

To prevent or detect melanomas (and increase survival rates), it is recommended that the public[18]:

- Learn what they look like (see "ABCDE" mnemonic below.)

- Are aware of moles and check for changes (shape, size, color, itching or bleeding)

- Show any suspicious moles to a doctor with an interest and skills in skin malignancy.

A popular method for remembering the signs and symptoms of melanoma is the mnemonic "ABCDE":

- Asymmetrical skin lesion.

- Border of the lesion is irregular.

- Color: melanomas usually have multiple colors.

- Diameter: moles greater than 5 mm are more likely to be melanomas than smaller moles.

- Evolution: The evolution (ie change) of a mole or lesion may be a hint that the lesion is becoming malignant --or-- Elevation: The mole is raised or elevated above the skin.

People with a personal or family history of skin cancer or of dysplastic nevus syndrome (multiple atypical moles) should see a dermatologist at least once a year to be sure they are not developing melanoma.

Diagnosis

Moles that are irregular in color or shape are suspicious of a malignant melanoma or a premalignant melanoma. Following a visual examination and a dermatoscopic exam (an instrument that illuminates a mole, revealing its underlying pigment and vascular network structure), the doctor may biopsy the suspicious mole. If it is malignant, the mole and an area around it needs excision. This may require a referral to a surgeon or dermatologist.

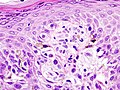

The diagnosis of melanoma requires experience, as early stages may look identical to harmless moles or not have any color at all. Where any doubt exists, the patient will be referred to a specialist dermatologist. Beyond this expert knowledge a biopsy performed under local anesthesia is often required to assist in making or confirming the diagnosis and in defining the severity of the melanoma.

Excisional biopsy is the management of choice; this is where the suspect lesion is totally removed with an adequate ellipse of surrounding skin and tissue.[19] The biopsy will include the epidermal, dermal, and subcutaneous layers of the skin, enabling the histopathologist to determine the depth of penetration of the melanoma by microscopic examination. This is described by Clark's level (involvement of skin structures) and Breslow's depth (measured in millimeters).

-

superficial spreading melanoma

If an excisional biopsy is not possible in certain larger pigmented lesions, a punch biopsy may by performed by a specialist hospital doctor, using a surgical punch (an instrument similar to a tiny cookie cutter with a handle, with an opening ranging in size from 1 to 6 mm). The punch is used to remove a plug of skin (down to the subcutaneous layer) from a portion of a large suspicious lesion, for histopathological examination.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) tests are often used to screen for metastases, although many patients with metastases (even end-stage) have a normal LDH; extraordinarily high LDH often indicates metastatic spread of the disease to the liver. It is common for patients diagnosed with melanoma to have chest X-rays and an LDH test, and in some cases CT, MRI, PET and/or PET/CT scans. Although controversial, sentinel lymph node biopsies and examination of the lymph nodes are also performed in patients to assess spread to the lymph nodes.

Sometimes the skin lesion may bleed, itch, or ulcerate, although this is a very late sign. A slow-healing lesion should be watched closely, as that may be a sign of melanoma. Be aware also that in circumstances that are still poorly understood, melanomas may "regress" or spontaneously become smaller or invisible - however the malignancy is still present. Amelanotic (colorless or flesh-colored) melanomas do not have pigment and may not even be visible. Lentigo maligna, a superficial melanoma confined to the topmost layers of the skin (found primarily in older patients) is often described as a "stain" on the skin. Some patients with metastatic melanoma do not have an obvious detectable primary tumor.

Types of Primary Melanoma

In the skin:

- Superficial spreading melanoma (SSM)

- Nodular melanoma

- Acral lentiginous melanoma

- Lentigo maligna melanoma

Any of the above types may produce melanin (and be dark in colour) or not (and be amelanotic - not dark). Similarly any subtype may show desmoplasia (dense fibrous reaction with neurotropism) which is a marker of aggressive behaviour and a tendency to local recurrence.

Elsewhere:

- Melanoma of soft parts

- Mucosal melanoma

- Uveal melanoma

- Menaloma under a finger or toe nail

Prognostic factors

Features that affect prognosis are tumor thickness in millimeters (Breslow's depth), depth related to skin structures (Clark level), type of melanoma, presence of ulceration, presence of lymphatic/perineural invasion, presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (if present, prognosis is better), location of lesion, presence of satellite lesions, and presence of regional or distant metastasis.[20]

Certain types of melanoma have worse prognoses but this is explained by their Breslow's depth. Interestingly, less invasive melanomas even with lymph node metastases carry a better prognosis than deep melanomas without regional metastasis at time of staging. Local recurrences tend to behave similarly to a primary unless they are at the site of a wide local excision (as opposed to a staged excision or punch/shave excision) since these recurrences tend to indicate lymphatic invasion.

When melanomas have spread to the lymph nodes, one of the most important factors is the number of nodes with malignancy. Extent of malignancy within a node is also important; micrometastases in which malignancy is only microscopic have a more favorable prognosis than macrometastases. In some cases micrometastases may only be detected by special staining, and if malignancy is only detectable by a rarely-employed test known as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the prognosis is better. Macrometastases in which malignancy is clinically apparent (in some cases cancer completely replaces a node) have a far worse prognosis, and if nodes are matted or if there is extracapsular extension, the prognosis is still worse.

When there is distant metastasis, the cancer is generally considered incurable. The five year survival rate is less than 10%.[21] The median survival is 6 to 12 months. Treatment is palliative, focusing on life-extension and quality of life. In some cases, patients may live many months or even years with metastatic melanoma (depending on the aggressiveness of the treatment). Metastases to skin and lungs have a better prognosis. Metastases to brain, bone and liver are associated with a worse prognosis.

There is not enough definitive evidence to adequately stage, and thus give a prognosis for ocular melanoma and melanoma of soft parts, or mucosal melanoma (e.g. rectal melanoma), although these tend to metastasize more easily. Even though regression may increase survival, when a melanoma has regressed, it is impossible to know its original size and thus the original tumor is often worse than a pathology report might indicate.

Staging

Further context on cancer staging is available at TNM.

Melanoma stages[21]:

Stage 0: Melanoma in Situ (Clark Level I), 100% Survival

Stage I/II: Invasive Melanoma, 85-95% Survival

- T1a: Less than 1.00 mm primary, w/o Ulceration, Clark Level II-III

- T1b: Less than 1.00 mm primary, w/Ulceration or Clark Level IV-V

- T2a: 1.00-2.00 mm primary, w/o Ulceration

Stage II: High Risk Melanoma, 40-85% Survival

- T2b: 1.00-2.00 mm primary, w/ Ulceration

- T3a: 2.00-4.00 mm primary, w/o Ulceration

- T3b: 2.00-4.00 mm primary, w/ Ulceration

- T4a: 4.00 mm or greater primary w/o Ulceration

- T4b: 4.00 mm or greater primary w/ Ulceration

Stage III: Regional Metastasis, 25-60% Survival

- N1: Single Positive Lymph Node

- N2: 2-3 Positive Lymph Nodes OR Regional Skin/In-Transit Metastasis

- N3: 4 Positive Lymph Nodes OR Lymph Node and Regional Skin/In Transit Metastases

Stage IV: Distant Metastasis, 9-15% Survival

- M1a: Distant Skin Metastasis, Normal LDH

- M1b: Lung Metastasis, Normal LDH

- M1c: Other Distant Metastasis OR Any Distant Metastasis with Elevated LDH

Based Upon AJCC 5-Year Survival With Proper Treatment

Treatment

Treatment of advanced malignant melanoma is performed from a multidisciplinary approach including dermatologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, surgical oncologists, general surgeons, plastic surgeons, neurologists, neurosurgeons, otorynolaryngologists, radiologists, pathologists/dermatopathologists, research scientists, nurse practitioners and physician assistants, and palliative care experts. Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are qualified to evaluate and treat patients on behalf of their supervising physicians.

Surgery

Diagnostic punch or excisional biopsies may appear to excise (and in some cases may indeed actually remove) the tumor, but further surgery is often necessary to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Complete surgical excision with adequate margins and assessment for the presence of detectable metastatic disease along with short and long term follow up is standard. Often this is done by a "wide local excision" (WLE) with 1 to 2cm margins. The wide excision aims to reduce the rate of tumour recurrence at the site of the original lesion. This is a common pattern of treatment failure in melanoma. Considerable research has aimed to elucideate appropriate margins for excision with a general trend toward less aggressive treatment druing the last decades. There seems to be no advantage to taking in excess of 2cm margins for even the thickest tumors.

More recently, a contoversial treatment option, Moh's micrographic surgery is becoming increasingly popular for smaller melanomas, especially of the face. In this surgery, performed by specially-trained dermatologists, a small layer of tissue is excised and prepared as a frozen tissue section. This section can be prepared and examined by the dermatologist/dermatopathologist within one hour, and the patient will return for further stages of excision as needed, with each excised tissue layer being examined until clear margins are obtained.[22]

The benefits of Moh's surgery specific to melanoma however, would appear to be minimal as margins of excision are reliably obtained visually and local recurrence rates historically have gone up with inadequate excisions. Deviation from recomended 1-2cm margins of excision should thus be approached carefully.

Melanomas which spread usually do so to the lymph nodes in the region of the tumour before spreading elsewhere. Attempts to improve survival by removing lymph nodes surgically (lymphadenectomy) were associated with many complications but unfortunately no overall survival benefit. Recently the technique of sentinel lymph node biopsy has been developed to reduce the complications of lymph node surgery while allowing assessment of the involvement of nodes with tumour.

Although controversial and without prolonging survival, "sentinel lymph node" biopsy is often performed, especially for T1b/T2+ tumors, mucosal tumors, ocular melanoma and tumors of the limbs. A process called lymphoscintigraphy is performed in which a mildly radioactive tracer is injected at the tumor site in order to localize the "sentinel node(s)". Further precision is provided using a blue tracer dye and surgery is performed to biopsy the node(s). Routine H&E staining, and immunoperoxidase staining will be adequate to rule out node involvement. PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) tests on nodes, usually performed to test for entry into clinical trials, now demonstrate that many patients with a negative SLN actually had a small amount of malignancy in their nodes. Alternatively, a fine-needle aspiration may be performed, and is often used to test masses.

If a lymph node is positive, depending on the extent of lymph node spread, a radical lymph node dissection will often be performed, and most patients in otherwise good health will begin up to a year of high-dose interferon treatment, which has severe side effects, but is claimed by some to improve the patients prognosis. This claim is not however supported by research at this time.

Adjuvant treatment

Melanomas with greater involvement may require referral to a medical or surgical oncologist for adjuvant treatment.

Metastatic melanomas can be detected by X-rays, CT scans, MRIs, PET and PET/CTs, ultrasound, and LDH testing.

Chemotherapy and immunotherapy

Various chemotherapy agents are used, including dacarbazine (also termed DTIC), immunotherapy (with interleukin-2 (IL-2) or interferon (IFN)) as well as local perfusion are used by different centers. They can occasionally show dramatic success, but the overall success in metastatic melanoma is quite limited.[23] IL-2 (Proleukin®)is the first new therapy approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma in 20 years. Studies have demonstrated that IL-2 offers the possibility of a complete and long-lasting remission in this disease, although only in a small percentage of patients.[24] A number of new agents and novel approaches are under evaluation and show promise.[25]

Lentigo maligna melanoma treatment

Some superficial melanomas (lentigo maligna melanoma) have resolved with, an experimental treatment, imiquimod (Aldara®) topical cream, an immune enhancing agent. Application of this cream has been shown to decrease tumor size prior to surgery, reducing the invasiveness of the procedure. This treatment is used especially for smaller melanoma in situ lesions located in cosmetically sensitive regions. Several published studies demonstrate a 70% cure rate with this topical treatment. With lentigo maligna, surgical cure rates are no higher. Some dermasurgeons are combining the 2 methods: surgically excise the cancer, then treat the area with Aldara® cream post-operatively for 3 months.

Radiation and other therapies

Radiation therapy is often used after surgical resection for patients with locally or regionally advanced melanoma or for patients with unresectable distant metastases. It may reduce the rate of local recurrence but does not prolong survival.[26]

In research setting other therapies, such as gene therapy, may be tested.[27] Radioimmunotherapy of metastatic melanoma is currently under investigation.

References

- ^ Melanoma Death Rate Still Climbing

- ^ Cancer Stat Fact Sheets

- ^ Urteaga OB, Pack GT (1966). "On the antiquity of melanoma". Cancer. 19: 607–610.

- ^ Davis NCO. William Norris MD.: a pioneer in the study of melanoma. Med J Aust 1980; 1: 52-4.

- ^ Bodenham DC (1968). "A study of 650 observed malignant melanomas in the South West Region". Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 43: 218–239.

- ^ Laennec RTH (1806). "Sur les melanoses". Bulletin de la Faculte de Medecine de Paris. 1: 24–26.

- ^ Cooper, Samuel (1840). First lines of theory and practice of surgery. London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman.

- ^ Parkin D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. "Global cancer statistics, 2002". CA Cancer J Clin. 55 (2): 74–108. PMID 15761078.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Full text - ^ Lucas, R. Global Burden of Disease of Solar Ultraviolet Radiation, Environmental Burden of Disease Series, July 25, 2006; No. 13. News release, World Health Organization

- ^ Who is Most at Risk for Melanoma?

- ^ Wang SQ, Setlow R, Berwick M, Polsky D, Marghoob AA, Kopf AW, Bart RS Ultraviolet A and melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Mar;48(3):464-5.

- ^ Bliss J, Ford D, Swerdlow A, Armstrong B, Cristofolini M, Elwood J, Green A, Holly E, Mack T, MacKie R (1995). "Risk of cutaneous melanoma associated with pigmentation characteristics and freckling: systematic overview of 10 case-control studies. The International Melanoma Analysis Group (IMAGE)". Int J Cancer. 62 (4): 367–76. PMID 7635560.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller A, Mihm M (2006). "Melanoma". N Engl J Med. 355 (1): 51–65. PMID 16822996.

- ^ Rhodes A, Weinstock M, Fitzpatrick T, Mihm M, Sober A (1987). "Risk factors for cutaneous melanoma. A practical method of recognizing predisposed individuals". JAMA. 258 (21): 3146–54. PMID 3312689.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berwick M, Wiggins C. "The current epidemiology of cutaneous malignant melanoma". Front Biosci. 11: 1244–54. PMID 16368510.

- ^ Autier P (2005). "Cutaneous malignant melanoma: facts about sunbeds and sunscreen". Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 5 (5): 821–33. PMID 16221052.

- ^ Can Melanoma Be Prevented?

- ^ Friedman R, Rigel D, Kopf A. "Early detection of malignant melanoma: the role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin". CA Cancer J Clin. 35 (3): 130–51. PMID 3921200.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Swanson N, Lee K, Gorman A, Lee H (2002). "Biopsy techniques. Diagnosis of melanoma". Dermatol Clin. 20 (4): 677–80. PMID 12380054.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Homsi J, Kashani-Sabet M, Messina J, Daud A (2005). "Cutaneous melanoma: prognostic factors". Cancer Control. 12 (4): 223–9. PMID 16258493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Full text (PDF) - ^ a b Balch C, Buzaid A, Soong S, Atkins M, Cascinelli N, Coit D, Fleming I, Gershenwald J, Houghton A, Kirkwood J, McMasters K, Mihm M, Morton D, Reintgen D, Ross M, Sober A, Thompson J, Thompson J (2001). "Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma". J Clin Oncol. 19 (16): 3635–48. PMID 11504745.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Full text - ^ Bowen G, White G, Gerwels J (2005). "Mohs micrographic surgery". Am Fam Physician. 72 (5): 845–8. PMID 16156344.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Full text - ^ Bajetta E, Del Vecchio M, Bernard-Marty C, Vitali M, Buzzoni R, Rixe O, Nova P, Aglione S, Taillibert S, Khayat D (2002). "Metastatic melanoma: chemotherapy". Semin Oncol. 29 (5): 427–45. PMID 12407508.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Buzaid A (2004). "Management of metastatic cutaneous melanoma". Oncology (Williston Park). 18 (11): 1443–50, discussion 1457-9. PMID 15609471.

- ^ Danson S, Lorigan P (2005). "Improving outcomes in advanced malignant melanoma: update on systemic therapy". Drugs. 65 (6): 733–43. PMID 15819587.

- ^ Bastiaannet E, Beukema J, Hoekstra H (2005). "Radiation therapy following lymph node dissection in melanoma patients: treatment, outcome and complications". Cancer Treat Rev. 31 (1): 18–26. PMID 15707701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sotomayor M, Yu H, Antonia S, Sotomayor E, Pardoll D. "Advances in gene therapy for malignant melanoma". Cancer Control. 9 (1): 39–48. PMID 11907465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Full text (PDF)

External links

Melanoma websites

Patient information

- What You Need To Know About Moles and Dysplastic Nevi - patient information booklet from cancer.gov (PDF)

- MPIP: Melanoma patients information page