Solar cell

A solar cell (or a "photovoltaic" cell) is a semiconductor device that converts photons from the sun (solar light) into electricity. In general a solar cell that includes both solar and non-solar sources of light (such as photons from incandescent bulbs) is termed a photovoltaic cell. Fundamentally, the device needs to fulfill only two functions: photogeneration of charge carriers (electrons and holes) in a light-absorbing material, and separation of the charge carriers to a conductive contact that will transmit the electricity. This conversion is called the photovoltaic effect, and the field of research related to solar cells is known as photovoltaics.

Solar cells have many applications. They are particularly well suited to, and historically used in, situations where electrical power from the grid is unavailable, such as in remote area power systems, Earth orbiting satellites, handheld calculators, remote radiotelephones and water pumping applications. Assemblies of solar cells (in the form of modules or photovoltaic arrays) on building roofs can be connected through an inverter to the electricity grid, often in a net metering arrangement.

Three generations of development

The most common configuration of this device, the first generation photovoltaic, consists of a large-area, single layer p-n junction diode, which is capable of generating usable electrical energy from light sources with the wavelengths of solar light. These cells are typically made using silicon. However, successive generations of photovoltaic cells are currently being developed that may improve the photoconversion efficiency for future photovoltaics. The second generation of photovoltaic materials is based on multiple layers of p-n junction diodes. Each layer is designed to absorb a successively longer wavelength of light (lower energy), thus absorbing more of the solar spectrum and increasing the amount of electrical energy produced. The third generation of photovoltaics is very different from the other two, and is broadly defined as a semiconductor device which does not rely on a traditional p-n junction to separate photogenerated charge carriers. These new devices include dye sensitized cells, organic polymer cells, and quantum dot solar cells.

History

The term "photovoltaic" comes from the Greek phos meaning "light", and the name of the Italian physicist Volta, after whom the volt (and consequently voltage) are named. It means literally of light and electricity.

The photovoltaic effect was first recognised in 1839 by French physicist Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel. However it was not until 1883 that the first solar cell was built, by Charles Fritts, who coated the semiconductor selenium with an extremely thin layer of gold to form the junctions. The device was only around 1% efficient. Russell Ohl patented the modern solar cell in 1946 (US2402662, "Light sensitive device"). Sven Ason Berglund had a prior patent concerning methods of increasing the capacity of photosensitive cells. The modern age of solar power technology arrived in 1954 when Bell Laboratories experimentation with semiconductors accidentally found that silicon doped with certain impurities was very sensitive to light.

This resulted in the production of the first practical solar cells with a sunlight energy conversion efficiency of around 6 percent. This milestone created interest in producing and launching a geostationary communications satellite by providing a viable power supply. Russia launched the first artificial satellite in 1957, and the United States' first artificial satellite was launched in 1958. This was a crucial development which diverted funding from several governments into research for improved solar cells.

Applications and implementations

Solar cells are often electrically connected and encapsulated as a module, termed a photovoltaic array or solar panel. Solar panels often have a sheet of glass on the front (sun up) side with a resin barrier behind, allowing light to pass while protecting the semiconductor wafers from the elements (rain, hail, etc). Solar cells are also usually connected in series in modules, creating an additive voltage.

Theory

Simple explanation

- Photons in sunlight hit the solar panel and are absorbed by semiconducting materials, such as silicon.

- Electrons (negatively charged) are knocked loose from their atoms, allowing them to flow through the material to produce electricity. The complementary positive charges that are also created (like bubbles) are called holes and flow in the direction opposite of the electrons in a silicon solar panel.

- An array of solar panels converts solar energy into a usable amount of direct current (DC) electricity.

Optionally:

- The DC current enters an inverter.

- The inverter turns DC electricity into 120 or 230-volt AC (alternating current) electricity needed for home appliances.

- The AC power enters the utility panel in the house.

- The electricity is then distributed to appliances or lights in the house.

Photogeneration of charge carriers

When a photon hits a piece of silicon, one of three things can happen:

- the photon can pass straight through the silicon - this (generally) happens for lower energy photons,

- the photon can reflect off the surface,

- the photon can be absorbed by the silicon which either:

- Generates heat, OR

- Generates electron-hole pairs, if the photon energy is higher than the silicon band gap value.

Note that if a photon has an integer multiple of band gap energy, it can create more than one electron-hole pair. However, this effect is usually not significant in solar cells. The "integer multiple" part is a result of quantum mechanics and the quantization of energy.

When a photon is absorbed, its energy is given to an electron in the crystal lattice. Usually this electron is in the valence band, and is tightly bound in covalent bonds between neighboring atoms, and hence unable to move far. The energy given to it by the photon "excites" it into the conduction band, where it is free to move around within the semiconductor. The covalent bond that the electron was previously a part of now has one less electron - this is known as a hole. The presence of a missing covalent bond allows the bonded electrons of neighboring atoms to move into the "hole," leaving another hole behind, and in this way a hole can move through the lattice. Thus, it can be said that photons absorbed in the semiconductor create mobile electron-hole pairs.

A photon need only have greater energy than that of the band gap in order to excite an electron from the valence band into the conduction band. However, the solar frequency spectrum approximates a black body spectrum at ~6000 K, and as such, much of the solar radiation reaching the Earth is composed of photons with energies greater than the band gap of silicon. These higher energy photons will be absorbed by the solar cell, but the difference in energy between these photons and the silicon band gap is converted into heat (via lattice vibrations - called phonons) rather than into usable electrical energy.

Charge carrier separation

There are two main modes for charge carrier separation in a solar cell:

- drift of carriers, driven by an electrostatic field established across the device

- diffusion of carriers from zones of high carrier concentration to zones of low carrier concentration (following a gradient of electrochemical potential).

In the widely used p-n junction designed solar cells, the dominant mode of charge carrier separation is by drift. However, in non-p-n junction designed solar cells (typical of the third generation of solar cell research such as dye and polymer thin-film solar cells), a general electrostatic field has been confirmed to be absent, and the dominant mode of separation is via charge carrier diffusion.

The p-n junction

The most commonly known solar cell is configured as a large-area p-n junction made from silicon. As a simplification, one can imagine bringing a layer of n-type silicon into direct contact with a layer of p-type silicon. In practice, p-n junctions of silicon solar cells are not made in this way, but rather, by diffusing an n-type dopant into one side of a p-type wafer (or vice versa).

If a piece of p-type silicon is placed in intimate contact with a piece of n-type silicon, then a diffusion of electrons occurs from the region of high electron concentration (the n-type side of the junction) into the region of low electron concentration (p-type side of the junction). When the electrons diffuse across the p-n junction, they recombine with holes on the p-type side. The diffusion of carriers does not happen indefinitely however, because of an electric field which is created by the imbalance of charge immediately either side of the junction which this diffusion creates. The electric field established across the p-n junction creates a diode that promotes current to flow in only one direction across the junction. Electrons may pass from the n-type side into the p-type side, and holes may pass from the p-type side to the n-type side. This region where electrons have diffused across the junction is called the depletion region because it no longer contains any mobile charge carriers. It is also known as the "space charge region".

Connection to an external load

Ohmic metal-semiconductor contacts are made to both the n-type and p-type sides of the solar cell, and the electrodes connected to an external load. Electrons that are created on the n-type side, or have been "collected" by the junction and swept onto the n-type side, may travel through the wire, power the load, and continue through the wire until they reach the p-type semiconductor-metal contact. Here, they recombine with a hole that was either created as an electron-hole pair on the p-type side of the solar cell, or swept across the junction from the n-type side after being created there.

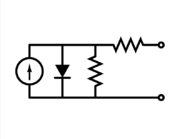

Equivalent circuit of a solar cell

To understand the electronic behaviour of a solar cell, it is useful to create a model which is electrically equivalent, and is based on discrete electrical components whose behaviour is well known. An ideal solar cell may be modelled by a current source in parallel with a diode. In practice no solar cell is ideal, so a shunt resistance and a series resistance component are added to the model. The result is the "equivalent circuit of a solar cell" shown on the left. Also shown on the right, is the schematic representation of a solar cell for use in circuit diagrams.

Solar cell efficiency factors

Maximum power point

A solar cell may operate over a wide range of voltages (V) and currents (I). By increasing the resistive load (voltage) in the cell from zero (indicating a short circuit) to infinitely high values (indicating an open circuit) one can determine the maximum power point (the maximum output electrical power, Vmax x Imax; or Pm, in watts).

Energy conversion efficiency

A solar cell's energy conversion efficiency (, "eta"), is the percentage of power converted (from absorbed light to electrical energy) and collected, when a solar cell is connected to an electrical circuit. This term is calculated using the ratio of Pm, divided by the input light irradiance under "standard" test conditions (E, in W/m2) and the surface area of the solar cell (Ac in m²).

At solar noon on a clear March or September equinox day, the solar radiation at the equator is about 1000 W/m2. Hence, the "standard" solar radiation (known as the "air mass 1.5 spectrum") has a power density of 1000 watts per square meter. Thus, a 12% efficiency solar cell having 1 m² of surface area in full sunlight at solar noon at the equator during either the March or September equinox will produce approximately 120 watts of peak power.

Fill factor

Another defining term in the overall behavior of a solar cell is the fill factor (FF). This is the ratio of the maximum power point divided by the open circuit voltage (Voc) and the short circuit current (Isc):

Quantum efficiency

Quantum efficiency refers to the percentage of absorbed photons that produce electron-hole pairs (or charge carriers). This is a term intrinsic to the light absorbing material, and not the cell as a whole (which becomes more relevant for thin-film solar cells). This term should not be confused with energy conversion efficiency, as it does not convey information about the power collected from the solar cell.

Comparison of energy conversion efficiencies

Silicon solar cell efficiencies vary from 6% for amorphous silicon-based solar cells to 30% or higher with multiple-junction research lab cells. Solar cell energy conversion efficiencies for commercially available mc-Si solar cells are around 14-16%. The highest efficiency cells have not always been the most economical -- for example a 30% efficient multijunction cell based on exotic materials such as gallium arsenide or indium selenide and produced in low volume might well cost one hundred times as much as an 8% efficient amorphous silicon cell in mass production, while only delivering a little under four times the electrical power.

To make practical use of the solar-generated energy, the electricity is most often fed into the electricity grid using inverters (grid-connected PV systems); in stand alone systems, batteries are used to store the electricity that is not needed immediately.

A common method used to express economic costs of electricity-generating systems is to calculate a price per delivered kilowatt-hour (kWh). The solar cell efficiency in combination with the available irradiation has a major influence on the costs, but generally speaking the overall system efficiency is important. Using the commercially available solar cells (as of 2006) and system technology leads to system efficiencies between 5 and 19%. As of 2005, photovoltaic electricity generation costs ranged from ~ 50 eurocents/kWh (0.60 US$/kWh) (central Europe) down to ~ 25 eurocents/kWh (0.30 US$/kWh) in regions of high solar irradiation. This electricity is generally fed into the electrical grid on the customer's side of the meter. The cost can be compared to prevailing retail electric pricing (as of 2005), which varied from between 0.04 and 0.50 US$/kWh worldwide. (Note: in addition to solar irradiance profiles, these costs/kwh calculations will vary depending on assumptions for years of useful life of a system. Most c-Si panels are warrantied for 25 years and should see 35+ years of useful life.)

The chart at the right illustrates the various commercial large-area module energy conversion efficiencies and the best laboratory efficiencies obtained for various materials and technologies.

Peak watt (or Watt peak)

Since solar cell output power depends on multiple factors, such as the sun's incidence angle, for comparison purposes between different cells and panels, the peak watt (Wp) is used. It is the output power under these conditions: [1]

- solar irradiance 1000 W/m²

- solar reference spectrum AM (airmass) 1.5

- cell temperature 25°C

Solar cells and energy payback

There is a common myth that solar cells never produce more energy than it takes to make them. While the expected working lifetime is around 40 years, the energy payback time of a solar panel is anywhere from 1 to 30 years (usually under five) depending on the type and where it is used (see net energy gain). This means solar cells can be net energy producers and can "reproduce" themselves (from just over once to more than 30 times) over their lifetime.[1] [2]

Light-absorbing materials

All solar cells require a light absorbing material contained within the cell structure to absorb photons and generate electrons via the photovoltaic effect. The materials used in solar cells tend to have the property of preferentially absorbing the wavelengths of solar light that reach the earth surface; however, some solar cells are optimized for light absorption beyond Earth's atmosphere as well. Light absorbing materials can often be used in multiple physical configurations to take advantage of different light absorption and charge separation mechanisms (listed in alphabetical order). Many currently available solar cells are configured as bulk materials that are subsequently cut into wafers and treated in a "top-down" method of synthesis (silicon being the most prevalent bulk material). Other materials are configured as thin-films (inorganic layers, organic dyes, and organic polymers) that are deposited on supporting substrates, while a third group are used as quantum dots (electron-confined nanoparticles) embedded in a supporting matrix in a "bottom-up" approach. Silicon remains the only material that is well-researched in both bulk and thin-film configurations.

Bulk

These bulk technologies are often referred to as wafer-based manufacturing. In other words, in each of these approaches, self-supporting wafers between 180 to 240 micrometers thick are processed and then soldered together to form a solar cell module. A general description of silicon wafer processing is provided in Manufacture and Devices.

Silicon

By far, the most prevalent bulk material for solar cells is crystalline silicon (abbreviated as a group as c-Si), also known as "solar grade silicon". Bulk silicon is separated into multiple categories according to crystallinity and crystal size in the resulting ingot, ribbon, or wafer.

- monocrystalline silicon (c-Si): often made using the Czochralski process. Single-crystal wafer cells tend to be expensive, and because they are cut from cylindrical ingots, do not completely cover a square solar cell module without a substantial waste of refined silicon. Hence most c-Si panels have uncovered gaps at the corners of four cells.

- Poly- or multicrystalline silicon (poly-Si or mc-Si): made from cast square ingots - large blocks of molten silicon carefully cooled and solidified. These cells are less expensive to produce than single crystal cells but are less efficient.

- Ribbon silicon: formed by drawing flat thin films from molten silicon and having a multicrystalline structure. These cells have lower efficiencies than poly-Si, but save on production costs due to a great reduction in silicon waste, as this approach does not require sawing from ingots.

Thin films

The various thin-film technologies currently being developed reduce the amount (or mass) of light absorbing material required in creating a solar cell. This can lead to reduced processing costs from that of bulk materials (in the case of silicon thin films) but also tends to reduce energy conversion efficiency, although many multi-layer thin films have efficiencies above those of bulk silicon wafers.

CdTe

Cadmium telluride is an efficient light absorbing material for thin-film solar cells. However, Cd is also regarded as a toxic heavy metal in the USA, reducing the incentive for development in that country.

CIGS

CIGS are multi-layered thin-film composites. The abbreviation stands for copper indium gallium selenide. Unlike the basic silicon solar cell, which can be modelled as a simple p-n junction (see under semiconductor), these cells are best described by a more complex heterojunction model. The best efficiency of a thin-film solar cell as of December 2005 was 19.5% with CIGS. Higher efficiencies (around 30%) can be obtained by using optics to concentrate the incident light. As of 2006, the best conversion efficiency for flexible CIGS cells on polyimide is 14.1% by Tiwari et al, at the ETH, Switzerland. The California start-up, Nanosolar, which claims to revolutionize the industry with its printable cells, uses flexible CIGS cells.

The use of indium increases the bandgap of the CIGS layer, gallium is added to replace as much indium as possible due to gallium's relative availability to indium. Selenium allows for better uniformity across the layer and so the number of recombination sites in the film are reduced which benefits the quantum efficiency and thus the conversion efficiency.

CIS

CIS is an abbreviation for general chalcogenide films of copper indium selenide (CuInSe2). While these films can achieve 11% efficiency, their manufacturing costs are high at present but continuing work is leading to more cost-effective production processes.

Gallium arsenide (GaAs) multijunction

High-efficiency cells have been developed for special applications such as satellites and space exploration which require high-performance. These multijunction cells consist of multiple thin films produced using molecular beam epitaxy. A triple-junction cell, for example, may consist of the semiconductors: GaAs, Ge, and GaInP2 [2]. Each type of semiconductor will have a characteristic band gap energy which, loosely speaking, causes it to absorb "light" most efficiently at a certain "color", or more precisely, to absorb electromagnetic radiation over a portion of the spectrum. The semiconductors are carefully chosen to absorb nearly all of the solar spectrum, thus generating electricity from as much of the solar energy as possible. GaAs multijunction devices are the most efficient solar cells to date, reaching as high as 39% efficiency [3]. They are also some of the most expensive cells per unit area (up to US$40/cm²).

Light absorbing dyes

Typically a Ruthenium metalorganic dye (Ru-centered) used as a monolayer of light-absorbing material. The dye-sensitized solar cell depends on a mesoporous layer of nanoparticulate titanium dioxide to greatly amplify the surface area (200-300 m²/gram TiO2, as compared to approximately 10 m²/gram of flat single crystal). The photogenerated electrons from the light absorbing dye are passed on to the n-type TiO2, and the holes are passed to an electrolyte on the other side of the dye. The circuit is completed by a redox couple in the electrolyte, which can be liquid or solid. This type of cell allows a more flexible use of materials, and typically are manufactured by screen printing, with the potential for lower processing costs than those used for bulk solar cells. However, the dyes in these cells also suffer from degradation under heat and UV light, and the cell casing is difficult to seal due to the solvents used in assembly. In spite of the above, this is a popular emerging technology with some commercial impact forecasted within this decade.

Organic/polymer solar cells

Organic solar cells and Polymer solar cells are built from thin films (typically 100 nm) of organic semiconductors such as polymers and small-molecule compounds like polyphenylene vinylene, copper phthalocyanine (a blue or green organic pigment) and carbon fullerenes. Energy conversion efficiencies achieved to date using conductive polymers are low at 4-5% efficiency for the best cells to date. However, these cells could be beneficial for some applications where mechanical flexibility and disposability are important.

Silicon

Silicon thin-films are mainly deposited by Chemical vapor deposition (typically plasma enhanced (PE-CVD)) from silane gas and hydrogen gas. Depending on the deposition's parameters, this can yield:

- Amorphous silicon (a-Si or a-Si:H)

- protocrystalline silicon or

- Nanocrystalline silicon (nc-Si or nc-Si:H).

These types of silicon present dangling and twisted bonds, which results in deep defects (energy levels in the bandgap) as well as deformation of the valence and conduction bands (band tails). The solar cells made from these materials tend to have lower energy conversion efficiency than bulk silicon, but are also less expensive to produce. The quantum efficiency of thin film solar cells is also lower due to reduced number of collected charge carriers per incident photon.

Amorphous silicon has a higher bandgap (1.7 eV) than crystalline silicon (c-Si) (1.1 eV), which means it is more efficient to absorb the visible part of the solar spectrum, but it fails to collect the infrared portion of the spectrum. As nc-Si has about the same bandgap as c-Si, the two material can be combined in thin layers, creating a layered cell called a tandem cell. The top cell in a-Si absorbs the visible light and leaves the infrared part of the spectrum for the bottom cell in nanocrystalline Si. A silicon thin film technology is being developed for building integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) in the form of semi-transparent solar cells which can be applied as window glazing. These cells function as window tinting while generating electricity.

These dimensionally confined structures make use of some of the same light absorbing materials from thin-film configurations, but are suspended in a supporting matrix of conductive polymer or mesoporous metal oxide.

Concentrating Photovoltaics (CPV)

Concentrating photovoltaic systems use a large area of lenses or mirrors to focus sunlight on a small area of photovoltaic cells. [3] These systems use single or dual-axis tracking to improve performace. The primary attraction of CPV systems is their reduced usage of semiconducting material which is expensive and currently in short supply. Additionally, increasing the concentration ratio improves the performance of general photovoltaic materials [4] and also allows for the use of high-performance materials such as gallium arsenide.[5]

Despite the advantages of CPV technologies their application has been limited by the costs of focusing, tracking and cooling equipment. For an example of a concentrating system under development using a silicon solar cell, see the recent experimental "Sunflower".

Silicon solar cell device manufacture

Because solar cells are semiconductor devices, they share many of the same processing and manufacturing techniques as other semiconductor devices such as computer and memory chips. However, the stringent requirements for cleanliness and quality control of semiconductor fabrication are a little more relaxed for solar cells. Most large-scale commercial solar cell factories today make screen printed poly-crystalline silicon solar cells. Single crystalline wafers which are used in the semiconductor industry can be made into excellent high efficiency solar cells, but they are generally considered to be too expensive for large-scale mass production.

Poly-crystalline silicon wafers are made by wire-sawing block-cast silicon ingots into very thin (180 to 350 micrometer) slices or wafers. The wafers are usually lightly p-type doped. To make a solar cell from the wafer, a surface diffusion of n-type dopants is performed on the front side of the wafer. This forms a p-n junction a few hundred nanometers below the surface.

Antireflection coatings, which increase the amount of light coupled into the solar cell, are typically applied next. Over the past decade, silicon nitride has gradually replaced titanium dioxide as the antireflection coating of choice because of its excellent surface passivation qualities (i.e., it prevents carrier recombination at the surface of the solar cell). It is typically applied in a layer several hundred nanometers thick using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). Some solar cells have textured front surfaces that, like antireflection coatings, serve to increase the amount of light coupled into the cell. Such surfaces can usually only be formed on single-crystal silicon, though in recent years methods of forming them on multicrystalline silicon have been developed.

The wafer is then metallized, whereby a full area metal contact is made on the back surface, and a grid-like metal contact made up of fine "fingers" and larger "busbars" is screen-printed onto the front surface using a silver paste. The rear contact is also formed by screen-printing a metal paste, typically aluminium. Usually this contact covers the entire rear side of the cell, though in some cell designs it is printed in a grid pattern. The metal electrodes will then require some kind of heat treatment or "sintering" to make Ohmic contact with the silicon. After the metal contacts are made, the solar cells are interconnected in series (and/or parallel) by flat wires or metal ribbons, and assembled into modules or "solar panels". Solar panels have a sheet of tempered glass on the front, and a polymer encapsulation on the back. Tempered glass cannot be used with amorphous silicon cells because of the high temperatures during the deposition process.

Current research on materials and devices

There are currently many research groups active in the field of photovoltaics in universities and research institutions around the world. This research can be divided into three areas: making current technology solar cells cheaper and/or more efficient to effectively compete with other energy sources; developing new technologies based on new solar cell architectural designs; and developing new materials to serve as light absorbers and charge carriers.

Silicon processing

One way of doing this is to develop cheaper methods of obtaining silicon that is sufficiently pure. Silicon is a very common element, but is normally bound in silica, or silica sand. Processing silica (SiO2) to produce silicon is a very high energy process, and more energy efficient methods of synthesis are not only beneficial to the solar industry, but also to industries surrounding silicon technology as a whole.

The current industrial production of silicon is via the reaction between carbon (charcoal) and silica at a temperature around 1700 degrees Celsius. In this process, known as carbothermic reduction, each tonne of silicon (metallurgical grade, about 98% pure) is produced with the emission of about 1.5 tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Solid silica can be directly converted (reduced) to pure silicon by electrolysis in a molten salt bath at a fairly mild temperature (800 to 900 degrees Celsius). [6][7] While this new process is in principle the same as the FFC Cambridge Process which was first discovered in late 1996, the interesting laboratory finding is that such electrolytic silicon is in the form of porous silicon which turns readily into a fine powder, (with a particle size of a few micrometres), and may therefore offer new opportunities for development of solar cell technologies.

Another approach is also to reduce the amount of silicon used and thus cost, as done by Australian National University in production of their "Sliver" cells, by micromachining wafers into very thin, virtually transparent layers that could be used as transparent architectural coverings. Using this technique, two silicon wafers are enough to build a 140 watt panel, compared to about 60 wafers needed for conventional modules of same power output.

Yet another way to achieve cost improvements is to reduce wastes during the crystal formation by improved modelisation of the process, as done by FemagSoft, spin-off of the Université Catholique de Louvain.

Thin-film processing

Thin-film solar cells use less than 1% of the raw material (silicon or other light absorbers) compared to wafer based solar cells, leading to a significant price drop per kWh. There are many research groups around the world actively researching different thin-film approaches and/or materials, however it remains to be seen if these solutions can generate the same space-efficiency as traditional silicon processing.

One particularly promising technology is crystalline silicon thin films on glass substrates. This technology makes use of the advantages of crystalline silicon as a solar cell material, with the cost savings of using a thin-film approach.

Another interesting aspect of thin-film solar cells is the possibility to deposit the cells on all kind of materials, including flexible substrates (PET for example), which opens a new dimension for new applications.

Polymer processing

The invention of conductive polymers (for which Alan Heeger, Alan G. MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa were awarded a Nobel prize) may lead to the development of much cheaper cells that are based on inexpensive plastics. However, all organic solar cells made to date suffer from degradation upon exposure to UV light, and hence have lifetimes which are far too short to be viable. The conjugated double bond systems in the polymers, which carry the charge, are always susceptible to breaking up when radiated with shorter wavelengths. This is due to the highly bipolar nature of the polymers. Additionally, conductive polymers are highly sensitive to air and water, making commercial applications difficult.

Nanoparticle processing

Experimental non-silicon solar panels can be made of quantum heterostructures, eg. carbon nanotubes or quantum dots, embedded in conductive polymers or mesoporous metal oxides. By varying the size of the quantum dots, the cells can be tuned to absorb different wavelengths. Although the research is still in its infancy, quantum dot-modified photovoltaics may be able to achieve up to 42 percent energy conversion efficiency due to multiple exciton generation.[8]

Despite the advantages of CPV technologies their application has been limited by the costs of focusing, tracking and cooling equipment. For an example of a concentrating system under development using a silicon solar cell, see the recent experimental "Sunflower".

Transparent Conductors

Many new solar cells use transparent thin films that are also conductors of electrical charge. The dominant conductive thin films used in research now are transparent conductive oxides (abbreviated "TCO"), and include fluorine-doped tin oxide (SnO2:F, or "FTO"), doped zinc oxide (e.g.: ZnO:Al), and indium tin oxide (abbreviated "ITO"). These conductive films are also used in the LCD industry for flat panel displays. The dual function of a TCO allows light to pass through a substrate window to the active light absorbing material beneath, and also serves as an ohmic contact to transport photogenerated charge carriers away from that light absorbing material. The present TCO materials are effective for research, but perhaps are not yet optimized for large-scale photovoltaic production. They require very special deposition conditions at high vacuum, they can sometimes suffer from poor mechanical strength, and most have poor transmittance in the infrared portion of the spectrum (e.g.: ITO thin films can also be used as infrared filters in airplane windows). These factors make large-scale manufacturing more costly.

A relatively new area has emerged using carbon nanotube networks as a transparent conductor for organic solar cells. Nanotube networks are flexible and can be deposited on surfaces a variety of ways. With some treatment, nanotube films can be highly transparent in the infrared, possibly enabling efficient low bandgap solar cells. Nanotube networks are p-type conductors, whereas traditional transparent conductors are exclusively n-type. The availability of a p-type transparent conductor could lead to new cell designs that simplify manufacturing and improve efficiency.

See also

- Autonomous building

- Future energy development

- Green technology

- Helianthos

- Photodiode

- Photovore

- Renewable energy

- Solar Engine

- Solar power

- Solar panel

- Solar tracker

- Timeline of solar energy

- Dye-sensitized solar cells

- Photovoltaics

References

- ^ "Net Energy Analysis For Sustainable Energy Production From Silicon Based Solar Cells" (PDF).

- ^ "What is the Energy Payback for PV?".

- ^ http://www.nrel.gov/news/press/release.cfm/release_id=10

- ^ http://www.nrel.gov/ncpv/new_in_cpv.html

- ^ http://www.spectrolab.com/

- ^ T. Nohira et al, ‘Pinpoint and bulk electrochemical reduction of insulating silicon dioxide to silicon’, Nat. Mater., 2 (2003) 397.

- ^ X. B. Jin et al, Electrochemical preparation of silicon and its alloys from solid oxides in molten calcium chloride’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 43 (2004) 733.

- ^ "Peter Weiss". "Quantum-Dot Leap". Science News Online. Retrieved 2005-06-17.

- McDonald SA, Konstantatos G, Zhang S, Cyr PW, Klem EJ, Levina L, Sargent EH (2005). "Solution-processed PbS quantum dot infrared photodetectors and photovoltaics". Nature Materials. 4 (2): 138–42. PMID 15640806.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - PVNET European Roadmap for PV R&D Ed Arnulf Jager-Waldan Office for Publications of the European Union 2004

External links

- Animation of how a solar cell works

- Carbon Nanotube Solar Cells (28 February 2005)

- Dye sensitized solar cells

- Examples of Silicon Photovoltaic Systems

- Flexible Silicon Solar Cells (15 February 2003)

- Historical: Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conversion: An Update (M. Green, 1998)

- Howstuffworks.com: How Solar Cells Work

- Organic Photovoltaics and Materials - Overview

- Organic Solar Cells for the Near-Infrared Spectrum

- Photovoltaic Residential Benefits

- Photovoltaic Solar Panel Overview

- Photovoltaic Thin Films for the Full Solar Spectrum (W. Walukiewicz 2002)

- Polymer-Nanoparticle Composite Solar Cell (29 March 2002)

- PV-Thermal Collector Development (Zondag et al, 2004)

- Residential Solar Power Systems - Photo Gallery

- PATH Tech Inventory: Photovoltaic Shingles

- Zero Energy Homes (ZEH)

- Residential Solar Information, Installation, and Repair

- Solar Energy Timeline

- Use of Solar Cells in Kenya and Uganda, in Africa

- Pliable solar cells are on a roll

Yield data

Theory

- Practical Course on Solar Modules

- Current/Voltage Measurements and Efficiency Factors

- Electrical models of solar cells

Dye solar cells

- Dye Solar Cell technology commercialising Dye Solar Cell technology

Cost benefit

Do-it-yourself

- PEC (Photo Electro Chromic)

- How to Build Your Own Solar Cell

- DIY (Do It Yourself): Nanocrystalline Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Kit Quote: "... sunlight-to-electrical energy conversion efficiency is between 1 and 0.5 %..."

- Cuprous oxide solar cells

- Make a Solar Cell in Your Kitchen, A Flat Panel Solar Battery

- From: How to Build a Solar Cell That Really Works by Walt Noon