Harry R. Truman

Harry R. Truman | |

|---|---|

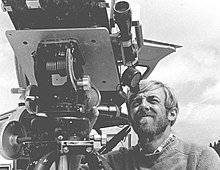

Harry R. Truman near his lodge on Spirit Lake, April 1980 | |

| Born | October 1896 West Virginia, United States |

| Died | May 18, 1980 (aged 83) Mount St. Helens, Washington, United States |

| Cause of death | Killed by volcano eruption Pyroclastic flow |

| Occupation(s) | Owner and operator of Mount St. Helens Lodge |

Harry R. Truman (October 1896 – May 18, 1980) was a resident of the U.S. state of Washington who lived on Mount St. Helens. The owner and caretaker of Mount St. Helens Lodge at Spirit Lake, at the foot of the mountain, he came to brief fame as a folk hero in the months preceding the volcano's 1980 eruption after he stubbornly refused to leave his home despite evacuation orders. Truman was presumed to have been killed by a pyroclastic flow that overtook his lodge and buried the site under 150 feet (46 m) of volcanic debris.

After Truman's death, his family and friends reflected on his love for the mountain. In 1981, Art Carney portrayed Truman in the docudrama film St. Helens. He was commemorated in a book by his niece and a number of musical pieces, including songs by Headgear and Billy Jonas.

Life

Harry R. Truman was born to foresters in West Virginia, in the United States, in October 1896. He did not know his exact birth date, though he gave his birth date as October 30, 1896.[1] While some non-contemporaneous sources have given his middle name as Randall,[2][3] Truman stated that he did not know his middle name, but rather just the initial, R.[4][5] Drawn to the promise of cheap land and the successful timber industry, his family moved west to Washington state, settling on a plot of farmland with an area of 160 acres (0.65 km2) in the eastern portion of Lewis County.[4] After attending high school in the city of Mossyrock, Truman enlisted in World War I, training as a aeromechanic and serving for two years in France.[4] During his service, he contracted a number of injuries due to his audacious and independent nature.[1] He also survived a torpedo attack on a troopship off of Ireland.[6] After the war, Truman sought success in prospecting, though he failed to achieve his goal of becoming rich. He became a bootlegger, smuggling alcohol from San Francisco to Washington state despite Prohibition.[1] At some point, Truman returned to Washington, moving to Chehalis, where he ran a gas service station called Harry's Sudden Service.[4] He also married his first wife, the daughter of a sawmill owner, with whom he had one daughter.[3]

Truman grew tired of civilization after a few years and leased a site of 50 acres (0.20 km2) from the Northern Pacific Railroad Company.[4] He used it to settle in the wilderness near Mount St. Helens,[1] a stratovolcano located in Skamania County, Washington. He opened another gas station here, in addition to a grocery store,[7] eventually opening the Mount St. Helens Lodge[1] close to the outlet of Spirit Lake,[8] which he operated for more than 50 years.[2]

During the 1930s, Truman divorced his first wife; he remarried in 1935. The second marriage was short, as Truman reportedly attempted to win arguments with his second wife by throwing her into Spirit Lake, despite her inability to swim. He began dating a local girl, though he eventually married this girl's sister, Edna, whom he called Eddie.[9] They remained married, operating the Mount St. Helens Lodge together[10] until Edna's death from a heart attack.[11]

In the Mount St. Helens area, Truman garnered notoriety for his antics, once getting a forest ranger drunk so that he could burn a pile of brush.[1] He illegally poached, stole gravel from the National Park Service, and fished on Native American land with a fake game warden badge. Despite their knowledge of these criminal activities, local rangers failed to catch him in the act. After the Washington state government passed a change to the state sales tax, Truman kept charging the same price. When a customer who worked at a tax agency renting a boat refused to pay his tax rate, Truman pushed him into Spirit Lake.[12]

A fan of the cocktail drink Schenley Whisky and Coke, Truman owned a pink 1957 Cadillac car, and he swore frequently.[13] He loved discussing politics and reportedly hated Republicans, along with hippies, young children, and especially old people. Once, Truman rejected Supreme Court Associate Justice William O. Douglas from staying at his lodge, dismissing him as an "old coot".[12] Upon realizing Douglas's identity, Truman changed his mind, chased him for 1 mile (1.6 km) and convinced him to stay.[12]

When his wife Edna died in 1978, Truman closed his lodge and only lent out a handful of boats and cabins every summer.[10]

Celebrity

Because of his cantankerous nature, Truman became a minor celebrity during the two months of volcanic activity preceding the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, giving interviews to reporters and expressing his opinion that the danger from the volcano was exaggerated, saying, "I don't have any idea whether it will blow [...] But I don't believe it to the point that I'm going to pack up."[14] Truman displayed little concern about the volcano and his situation, stating "If the mountain goes, I'm going with it. This area is heavily timbered, Spirit Lake is in between me and the mountain, and the mountain is a mile away, the mountain ain't gonna hurt me."[15] Law enforcement officials were incensed by Truman's refusal to evacuate, because media representatives kept entering the restricted zone near the volcano to interview him, endangering themselves in the process. Still, Truman remained steadfast, commenting, "You couldn't pull me out with a mule team. That mountain's part of Truman and Truman's part of that mountain."[12]

In an interview with news reporters, Truman said he responded to being knocked from his bed by precursor earthquakes by moving his mattress to his basement.[16] He claimed to wear spurs to bed to cope with the earthquakes while he slept.[17] At one point, Truman "scoffed"[16] at the public's concern for his safety,[16] responding to scientists' claims about the threat of the volcano that "the mountain has shot its wad and it hasn't hurt my place a bit, but those goddamn geologists with their hair down to their butts wouldn't pay no attention to ol' Truman."[12]

As a result of his defiant commentary, Truman became something of a "folk hero"[16] and from March until May, was the subject of many songs and poems by children.[18] One group of children from Salem, Oregon, sent him banners inscribed "Harry - We Love You", which moved him so much that he took a helicopter trip, paid for by National Geographic,[19] to visit them on May 14.[17] Truman also received many fan letters,[20] including several marriage proposals.[21] Another group of children—fifth graders from the city of Grand Blanc in Michigan—wrote Truman letters that brought him to tears. In return, he sent them a letter and volcanic ash, which the students later sold to buy flowers to send to Truman's family after the eruption.[19]

He attracted media frenzy, appearing on the front page of The New York Times and The San Francisco Examiner and garnering the attention of National Geographic, United Press International, and The Today Show.[22] Many major magazines composed profiles for Truman, including Time, Life, Newsweek, Field & Stream, and Reader's Digest. Historian Richard W. Slatta wrote that "few people would describe [Truman] as heroic," but "his fiery attitude, brash speech, love of the outdoors, and fierce independence [...] made him a folk hero the media could adore."[19] Analyzing Truman's rise to fame, Slatta cited "his unbendable character and response to the forces of nature", and he explained that interviews with Truman became critical "to add color" to reports about the events at Mount St. Helens.[23] As the only figure from the story recognizable on a national scale, Truman, he wrote, was "immortalized [...] as a figure with many of the embellished qualities of the western hero", and was "preserved by the national spotlight [...] in a romanticized form [...] in some ways quite different from his true character."[1]

Death

Over the course of the spring, as St. Helens progressively grew more likely to erupt, state officials tried to evacuate the area with the exception of a few scientists and security officials. On May 17, they attempted one final time to persuade Truman to leave, to no avail. The next morning, the volcano erupted, its entire northern flank collapsing.[24] Truman was alone at his lodge, where he lived with 16 cats,[2] when he is presumed to have died in the eruption on May 18.[20] A pyroclastic flow engulfed the Spirit Lake area, destroying the lake and burying the site of his lodge under 150 feet (46 m) of volcanic landslide debris.[24] Authorities never found Truman's remains.[2] Truman's 16 cats, which he considered family and mentioned in almost all public statements he made,[24] are presumed to have died with him on the day of the eruption.[2][24] At the time of his death, Truman had operated the Mount St. Helens lodge for 52 years.[16]

Friends hoped that Truman might have survived, as he had claimed to have provisioned an abandoned mine shaft with food and liquor in case of an eruption from Mount St. Helens. But the lack of warning of the incoming eruption likely prevented him from escaping to the shaft before the pyroclastic flow reached his lodge.[10] His sister Geraldine expressed that she found it hard to accept the reality of his death, commenting, "I don't think he made it. But I thought if they would let me fly over and see for myself that Harry's lodge is gone, then maybe I'd believe it for sure."[16] Reflecting on the eruption's 20-year anniversary, Truman's niece Shirley Rosen added that he thought he could escape the volcano, not expecting the lateral eruption. She stated that her sister brought Truman a bottle of Bourbon whiskey to convince him to evacuate, but he was too afraid to drink alcohol because he was unsure whether the shaking was coming from his body or the earthquakes from St. Helens.[6] His possessions were auctioned off as keepsakes to admirers in September.[25]

The 1980 event was the deadliest and most destructive volcanic eruption in the recorded history of the continental United States of America.[26] Approximately 57 people are known to have died,[27] and more were left homeless when the ash falls and pyroclastic flows destroyed or buried 200 houses.[26] In addition to Truman, photojournalist Reid Blackburn,[28] volcanologist David A. Johnston,[27] and photographer Robert Landsburg[29] were among those killed.

Legacy

Truman had already emerged as a "folk hero" for his resistance to the evacuation efforts prior to his death.[16] The Columbian, the daily newspaper for Vancouver and Clark County, wrote that "With his ten-dollar name and hell-no-I-won’t-go attitude, Truman was a made-for-prime-time folk hero."[13] After his death, his friends and family, including his sister, Geraldine (Geri), reflected on his death, commenting, "He was a very opinionated person."[18] Truman's friend John Garrity added, "The mountain and the lake were his life. If he'd left and then saw what the mountain did to his lake, it would have killed him anyway. He always said he wanted to die at Spirit Lake. He went the way he wanted to go."[18] Agreeing, Truman's niece Shirley retrospectively stated in an interview, "He used to say that's my mountain and my lake and he would say those are my arms and my legs. If he would have seen it the way it is now, I don't think he would have survived."[6] Similarly, Truman's friend John Andersen said that "Harry's name and Harry's presence will always be a part of that (Spirit Lake). There can be no finer memorial."[18] Truman's cousin Richard Ice commented that he "was not only a fast talker but loud. He had an opinion on all subjects and a definite one."[18] Ice also remarked that Truman's short period of life as a celebrity was "the peak of his life."[18]

Truman was the subject of the books Truman of St. Helens: The Man and His Mountain written by his niece Shirley Rosen[30] and The Legend Of Harry Truman written by his sister Geri,[31] and he was portrayed by Art Carney, a favorite actor of his,[32] in the 1981 docudrama film St. Helens.[33] After his death, memorabilia including Harry Truman hats, pictures, posters, and postcards were sold in the area surrounding Mount St. Helens. In Anchorage, a city in Alaska, a restaurant named after Truman was opened, serving dishes like Harry's Hot Molten Chili.[31] According to The Washington Star, by 1981, more than 100 songs had been composed in Truman's honor, in addition to a commemorative album titled The Musical Legend Of Harry Truman — A Very Special Collection Of Mount St. Helens’ Volcano Songs.[31] He is the subject of the 2007 indie rock song "Harry Truman"[34] written and recorded by Irish band Headgear.[35] Another song about Harry was written by Lula Belle Garland in 1980, called "The Legend of Harry And The Mountain," which was recorded in 1980 by Ron Shaw & The Desert Wind Band.[36] Musicians Ron Allen and Steve Asplund of the group R. W. Stone wrote a country rock song in 1980 about his story called "Harry Truman, Your Spirit Still Lives On".[34] More recently, singer-songwriter and family entertainer Billy Jonas included Truman's narrative in his song "Old St. Helen", which was copyrighted in 1993.[37]

Truman Trail and Harry's Ridge in the Mount St. Helens region are named after him.[38][39] Additionally, a park with a memorial to Truman in Castle Rock[40] was named the Harry R. Truman Memorial Park in his honor, though it was later renamed to the Castle Rock Lions Club Volunteer Park.[41]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Slatta 2001, p. 350.

- ^ a b c d e Grisham, Lori (May 17, 2015). "'I'm going to stay right here.' Lives lost in Mount St. Helens eruption". USA Today. Gannett Company. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Kean 2017, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e Gulick 1996, p. 268.

- ^ Findley 1981, p. 4.

- ^ a b c "One Man Refused To Leave". CBS News. CBS Corporation. May 18, 2000. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ Kean 2017, p. 17.

- ^ topoView Map (Map). United States Geological Survey. 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ Kean 2017, pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b c Findley 1981, p. 2.

- ^ Kean 2017, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e Slatta 2001, p. 351.

- ^ a b "The old man and the mountain". The Columbian. Columbian Publishing Co. April 1, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "83-year old Man Isn't Shaken by Mount St. Helens Earthquakes". Lawrence Journal-World. The World Company. March 25, 1980. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ Green, Carlson & Myers 2002, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mud, ash inundate old Truman's lodge". The Bulletin. Western Communications. May 21, 1980.

- ^ a b Findley 1981, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Associated Press / United Press International (June 16, 1980). "Family, friends say goodbye to Harry". The Deseret News.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Slatta 2001, p. 352.

- ^ a b Associated Press (May 20, 1980). "Sister, friend say Harry probably dead". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Cowles Publishing Company.

- ^ "Harry Truman feared lost on mountain". The Madison Courier. May 24, 1980. p. B5.

- ^ Slatta 2001, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Slatta 2001, pp. 349–350.

- ^ a b c d "Harry Truman and His 16 Cats". Center for Educational Technologies. Wheeling Jesuit University. January 27, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ "Harry Truman's possessions: an auction of memories". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. September 14, 1980. p. A24.

- ^ a b Tilling, Robert I.; Topinka, Lyn J.; Swanson, Donald A. (June 25, 1997). "Eruptions of Mount St. Helens : Past, present, and future - impact". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tilling, Robert I.; Topinka, Lyn J.; Swanson, Donald A. (June 25, 1997). "Eruptions of Mount St. Helens : Past, present, and future - The Climactic Eruption of May 18, 1980". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robinson, Erik (April 1, 2010). "Volcano's toll hits close to home". The Colombian. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- ^ Foxworthy & Hill 1982, p. 89.

- ^ Rosen 1981, p. 163.

- ^ a b c "Ballad of Harry Truman Hails folk hero" (PDF). The Washington Star. Time, Inc. September 1, 1981. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Harti, John (November 12, 1980). "St. Helens and Harry Truman wrupt on film". The Seattle Times. p. D3.

- ^ "St. Helens visits state". The Bulletin. Western Communications. January 1, 1981. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Gawande 2014, p. 270.

- ^ Guerin, Harry (June 1, 2007). "Headgear - Flight Cases". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "Mt. St. Helens: The mountain that slept 100 years and a man who loved that mountain". Billboard. Vol. 92, no. 32. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. August 16, 1980. p. 29.

- ^ Jonas, Billy. "Old St. Helen from What Kind Of Cat Are You?!". Billy Jonas Band. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "Trail #207 Truman (Willow Springs #207A)". United States Forest Service. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "Trail #1E Harry's Ridge". United States Forest Service. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ LaBoe, Barbara (May 4, 2008). "Castle Rock Lions turning park over to city". The Daily News. Lee Enterprises. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Kershaw, Sarah (October 14, 2004). "Buzz Was Big, but Mount St. Helens Eruption Wasn't". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

Sources

- Findley, R. (January 1981). "Mountain With a Death Wish". National Geographic. National Geographic Partners and National Geographic Society.

{{cite magazine}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Foxworthy, B. L.; Hill, M. (1982). Volcanic eruptions of 1980 at Mount St. Helens: the first 100 days (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper, 1249). United States Geological Survey. OCLC 631692808.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Gawande, A. (2014). Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1250081247.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Green, M. K.; Carlson, L. M.; Myers, S. A. (2002). Washington in the Pacific Northwest. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 978-0-87905-988-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Gulick, B. (1996). A Traveler's History of Washington. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-87004-371-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Kean, S. (2017). Caesar's Last Breath: Decoding the Secrets of the Air Around Us. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-38163-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Rosen, S. (1981). Truman of St. Helens: The Man & His Mountain. Seattle: Madrona Publishers; Longview: Longview Pub. Co. ISBN 0-914842-57-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Slatta, R. W. (2001). The Mythical West: An Encyclopedia of Legend, Lore, and Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576071519.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)