Battle of Lukaya

| Battle of Lukaya | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Uganda–Tanzania War | |||||||||

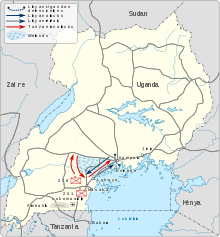

Libyan and Tanzanian troop movements during and after the battle | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

2 Tanzanian brigades 1 Ugandan rebel battalion (7,000 total soldiers) 3 tanks |

2,000 Ugandan soldiers (Tanzanian estimate) ~1,000 Libyan soldiers Several Palestinian guerrillas 18 tanks 12+ armoured personnel carriers | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

8+ Tanzanian soldiers killed 1 Ugandan rebel killed |

~200 Ugandan soldiers killed ~200 Libyan soldiers killed Unknown Palestinian casualties 1 Libyan soldier captured | ||||||||

The Battle of Lukaya was a battle of the Uganda–Tanzania War. It was fought between 10 and 11 March 1979 around Lukaya, Uganda, between Tanzanian forces (supported by Ugandan rebels) and Ugandan government forces (supported by Libyan and Palestinian troops). After briefly occupying the town, Tanzanian troops and Ugandan rebels retreated under artillery fire. The Tanzanians subsequently launched a counterattack, retaking Lukaya and killing hundreds of Libyans and Ugandans.

President Idi Amin of Uganda attempted to invade neighbouring Tanzania to the south in 1978. The attack was repulsed, and Tanzania launched a counterattack into Ugandan territory. In February 1979 the Tanzania People's Defence Force (TPDF) seized Masaka. The TPDF's 201st Brigade was then instructed to secure Lukaya and its causeway to the north, which served as the only direct route through a large swamp to Kampala, the Ugandan capital. Meanwhile, Amin ordered his forces to recapture Masaka, and a force was assembled for the purpose consisting of Ugandan troops, allied Libyan soldiers, and a handful of Palestine Liberation Organisation guerrillas, led by Lieutenant Colonel Godwin Sule.

On the morning of 10 March the TPDF's 201st Brigade under Brigadier Imran Kombe, bolstered by a battalion of Ugandan rebels, occupied Lukaya without incident. In the late afternoon the Libyans attacked the town with rockets, and the unit broke and fled into the nearby swamp. Tanzanian commanders ordered the 208th Brigade to march to the Kampala road to flank the Ugandan-Libyan force. At dawn on 11 March the 208th Brigade reached its target position and the Tanzanian counterattack began. The regrouped 201st Brigade assaulted the Libyans and Ugandans from the front and the 208th from their rear. Sule was killed, precipitating the collapse of the Ugandan defences, while the Libyans retreated. Hundreds of Ugandan government and Libyan troops were killed. The Battle of Lukaya was the largest engagement of the war. Amin's forces were adversely affected by the outcome, and Ugandan resistance crumbled in its wake. The TPDF was able to proceed up the road and later attack Kampala.

Background

In 1971 Colonel Idi Amin launched a military coup that overthrew the President of Uganda, Milton Obote, precipitating a deterioration of relations with neighbouring Tanzania.[1] Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere had close ties with Obote and had supported his socialist orientation.[2] Amin installed himself as President of Uganda and ruled the country under a brutal dictatorship.[1] Nyerere withheld diplomatic recognition of the new government and offered asylum to Obote and his supporters. He tacitly supported a failed attempt by Obote to overthrow Amin in 1972, and after a brief border conflict he and Amin signed a peace accord. Nevertheless, relations between the two presidents remained tense, and Amin made repeated threats to invade Tanzania.[2]

Uganda's economy languished under Amin's corrupt rule, and instability manifested in the armed forces. Following a failed mutiny in late October 1978, Ugandan troops crossed over the Tanzanian border in pursuit of rebellious soldiers. On 1 November Amin announced that he was annexing the Kagera Salient in northern Tanzania.[3] Tanzania halted the sudden invasion, mobilised anti-Amin opposition groups, and launched a counteroffensive.[4] Nyerere told foreign diplomats that he did not intend to depose Amin, but only "teach him a lesson".[5] The claim was not believed; Nyerere despised Amin, and he made statements to some of his colleagues about overthrowing him. The Tanzanian Government also felt that the northern border would not be secure unless the threat presented by Amin was eliminated.[5] After the Tanzania People's Defence Force (TPDF) retook northern Tanzania, Major General David Musuguri was appointed commander of the 20th Division and ordered to push into Ugandan territory.[6] In-mid February, Libyan troops were flown into Entebbe to assist the Uganda Army.[7] Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi felt that Uganda, a Muslim state in his view, was being threatened by a Christian army, and wished to halt the Tanzanians.[8]

On 24 February 1979 the TPDF seized Masaka. Nyerere originally planned to halt his forces there and allow Ugandan exiles to attack Kampala, the Ugandan capital, and overthrow Amin. He feared that scenes of Tanzanian troops occupying the city would reflect poorly on the country's image abroad. However, Ugandan rebel forces did not have the strength to defeat the incoming Libyan units, so Nyerere decided to use the TPDF to take the capital.[9] The fall of Masaka surprised and troubled Ugandan commanders, who felt that the defeat made Kampala vulnerable to attack. They mobilised additional forces and began planning for a defence of the city.[10] The Uganda Army also showed first signs of disintegrating, as various high-ranking commanders disappeared or were murdered. One Ugandan soldier stated in an interview with Drum, a South African magazine, that "the situation is worsening every day and therefore our days are numbered".[11] Meanwhile, the TPDF's 20th Division prepared to advance from Masaka to Kampala.[8]

Prelude

The only road from Masaka to Kampala passed through Lukaya, a town 39 kilometres (24 mi) to the north of the former. From there, the route continued on a 25-kilometre (16 mi) causeway that went through a swamp until it reached Nabusanke. The swamp was impassable for vehicles, and the destruction of the causeway would delay a Tanzanian attack on Kampala for months. Though the TPDF would be vulnerable on the passage, Musuguri ordered his troops to secure it.[8] The TPDF's 207th Brigade was dispatched through the swamp to the east, the 208th Brigade was sent west to conduct a wide sweep that would bring it around the northern end of the swamp, and the 201st Brigade under Brigadier Imran Kombe was to advance up the road directly into the town. The 201st consisted almost entirely of militiamen, many of whom had not seen combat. However, the unit was bolstered by a battalion of Ugandan rebels, led by Lieutenant Colonel David Oyite-Ojok.[12]

A plan to destroy the causeway was presented to Amin in Kampala, but he rejected it, saying that it would inhibit his army's ability to launch a counteroffensive against the Tanzanians. He also believed that with Libyan support the TPDF would soon be defeated, and thus destroying and then rebuilding the causeway later would be unnecessary.[8] On 9 March over a thousand Libyan troops and several Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) guerrillas were flown into Uganda.[12] The Libyan force included regular units, sections of the People's Militia, and members of the Pan-African Legion.[13][14] They were accompanied by 15 T-55 tanks, over a dozen armoured personnel carriers, multiple Land Rovers equipped with 106 mm (4.2 in) recoilless rifles, one dozen BM-21 Grad 12-barrel Katyusha rocket launcher variants,[12][15][13] and other large artillery pieces, such as 122 mm mortars[16] and two batteries of D-30 howitzers.[15] Amin ordered the Libyans, together with some Ugandan troops[a]—including the Artillery & Signals Regiment[18]—and PLO fighters, to recapture Masaka, and a force assembled for the purpose at the northern edge of the swamp between Lukaya and Buganga.[12][19][20][b] Lieutenant Colonel Godwin Sule, a paratrooper commander, was placed in charge of the operation.[22] The Libyan troops were briefed about it at Mitala Maria.[16] That evening the Ugandan forces present in Lukaya withdrew.[13]

Battle

10 March

On the morning of 10 March the TPDF conducted a light bombardment of Lukaya, which had been deserted by the populace. The 201st Brigade then occupied the town to await crossing the causeway the next day,[12] and they began to dig trenches as a precautionary measure.[18] The Tanzanians and the Ugandans and Libyans were unaware of each other's positions. In the late afternoon the Ugandan-Libyan-Palestinian force began its advance toward Lukaya, with orders to take Masaka within three hours. Upon seeing the Tanzanians at dusk, they initiated a barrage with the Katyusha rockets. The artillery overshot them, but the mostly inexperienced Tanzanian soldiers were frightened, and many of them broke rank and fled.[12] Though others remained at their defensive positions, they were nonetheless surprised and quickly forced to withdraw into the swamp along the Masaka road after seeing the Libyan T-55s and three Ugandan M4A1 Sherman tanks advancing toward them. Nobody was killed in the action.[18][23] Despite its orders to recapture Masaka, the Ugandan-Libyan force stopped in Lukaya,[24] fearing that the Tanzanians were trying to bait them into an ambush.[25][c] The Libyans established defensive positions but did not dig any trenches.[24] Only three Tanzanian tanks guarded the road.[29] Kombe and his subordinates tried to reassemble their brigade so it could continue fighting, but the soldiers were shaken and could not be organised.[25]

Tanzanian commanders decided to alter their plans to prevent the loss of Lukaya from turning into a debacle. The 208th Brigade under Brigadier Mwita Marwa, which was 60 kilometres (37 mi) north-west of the town, was ordered to reverse course and as quickly as possible cut off the Ugandans and Libyans from Kampala.[29][30] The tanks on the Masaka road were instructed to advance and open fire on the Ugandan and Libyan positions. Their drivers were hesitant to do so without infantry support, so Musuguri dispatched one of his officers to the area to ensure that the order was carried out. Volunteers were recruited from the 201st Brigade to infiltrate Lukaya through the swamp and gather intelligence. Overnight the situation was dominated by confusion; the Ugandan-Libyan-Palestinian force and the TPDF's 201st Brigade were disorganised, and troops from both sides moved around in the darkness (there was no moonlight) along the road and in the town, unable to differentiate between each other.[29][18] In one incident, Oyite-Ojok was leading a band of Kikosi Maalum (KM) fighters down the road when they heard other persons talking in Swahili. Oyite-Ojok and his group assumed they were allies, but then one of them said in Luo—a language not spoken in Tanzania, "Just wait until morning and we'll crush these stupid Acholi."[29] Oyite-Ojok instructed his men to open fire, but in the dark they were unable to verify if they had struck anybody.[29] The Tanzanian patrols were largely unsuccessful in verifying the Ugandan-Libyan positions, so their tanks' fire was ineffective.[31] Over the course of the night eight Tanzanian soldiers and one KM fighter were killed.[29]

11 March

The 208th Brigade reached its flanking position at the Kampala road at dawn on 11 March and began the counterattack.[29] The regrouped 201st Brigade attacked from the front and the 208th from behind, thereby putting great pressure on the Ugandan-Libyan force.[19][29] Precisely aimed Tanzanian artillery devastated their ranks,[29] particularly the TPDF's own Katyusha rockets.[16] The Ugandans and Libyans were surprised by the assault and could not muster an effective resistance.[32] Most of the Libyans subsequently began to retreat.[29] At his headquarters farther north, Ugandan Lieutenant Colonel Abdu Kisuule, commander of the Artillery & Signals Regiment,[18] was awakened by the withdrawing Libyans. He ordered Major Aloysius Ndibowa to block the Kampala road to curtail the retreat. He then moved towards the front from Kayabwe, while Sule assumed command of several tanks and drove towards the battle. Near the Katonga Bridge, Tanzanian forces took up positions in a eucalyptus forest on the western side of the road. They ambushed the Ugandans and Libyans, inflicting heavy casualties. Dozens of jeeps evacuated the wounded to Kampala.[16]

In an attempt to strengthen morale, Ugandan General Isaac Maliyamungu and Major General Yusuf Gowan joined their troops on the front line. For unknown reasons, the positions the two men took were frequently subject to sudden, intense rocket fire. Ugandan junior officers tried to convince their men that the Tanzanians were probably aware of the generals' presence and were targeting them with precise bombardments. The Ugandan troops nonetheless felt that Maliyamungu and Gowon were harbingers of misfortune and nicknamed them bisirani (English: bad omen).[d] Sule soon realised the generals were not having a positive effect and asked them to leave the front.[22] Sule was later killed after being accidentally run over by one his tanks while ordering it to reverse course to manoeuvre around a crater created by a Tanzanian artillery shell.[34] Kisuule had lost contact with him and was not aware of his fate until the next day.[16][e] His death prompted the collapse of the Ugandan command structure, and the remaining Ugandan troops abandoned their positions and fled.[36]

Aftermath

Casualties and losses

The Tanzanians later reported that 7,000 TPDF and Ugandan rebel soldiers participated in the battle.[17] After the battle, Tanzanian forces counted over 400 dead soldiers in the area, including about 200 Libyans.[29] More bodies were brought by retreating troops to Kampala.[16] Kayabwe residents later recalled seeing many Libyan bodies strewn across the Kampala road north of Lukaya and along the Katonga Bridge.[37] The Tanzanian soldiers were unwilling to take Libyan soldiers prisoner, instead shooting those they found, as their political officers in the previous days had told them that the Arabs were coming into Sub-Saharan Africa to re-establish slavery; a single wounded lance corporal was captured.[29] Three planes evacuated wounded Libyans from Kampala to Tripoli.[38] Tanzanian casualties were light.[19] After the Lukaya engagement, Uganda Radio claimed that 500 Tanzanians were killed and 500 were wounded. Ugandan opposition exiles claimed that 600 Ugandan government soldiers and an unspecified number of Libyans were killed. The Africa Research Bulletin dismissed the statistics, writing, "none of these figures is credible."[39] The Tanzanian government press claimed that two battalions of about 2,000 Ugandan soldiers were "annihilated".[40] Three tanks were also reported destroyed. Independent diplomatic sources acknowledged that immediate details of the battle were unclear, but labelled the inflicted casualties claimed by both belligerents as greatly exaggerated.[40][f] In a meeting with foreign diplomats on 15 March, Amin stated that his forces had suffered heavy losses, including the death of a lieutenant colonel and five captains.[42] The Ugandan–Libyan force left many weapons behind, as well as a copy of their battle plan, which was seized by the Tanzanians. The document revealed that Amin's troops were to eventually push further past Masaka and drive the TPDF out of Kalisizo.[43]

Strategic implications

Kisuule later said that Lukaya "was the last serious battle and that's where we lost the war."[16] Indian diplomat Madanjeet Singh stated that "it was essentially the Battle of Lukaya that had shattered the morale of Amin's army."[44] Idi Amin's son, Jaffar Remo Amin, said "The war ended at Lukaya when most of the soldiers and Secret Service personnel either said 'Congo na gawa' or 'Sudan na gawa' or high tailed it out of the country."[45] The historians Tom Cooper and Adrien Fontanellaz concluded that "after the Battle of Lukaya, the Uganda Army de-facto collapsed and ran."[46] Sule was one of the Uganda Army's most competent commanders, and his death had a detrimental impact on the force.[34] After the engagement, many Ugandan commanders withdrew from the front lines.[16] The Ugandan defeat in Lukaya cut off the communications of the Suicide Battalion in Sembabule from other Ugandan forces.[36] His situation becoming more desperate and his appeals to the United Nations, Arab League, and Organisation of African Unity having little effect, Amin requested that Pope John Paul II intervene and call for an end to the war.[31]

The Tanzanians publicly announced that they had complete control over Lukaya.[40] After the victory and eventual success at Sembabule, the TPDF held the strategic initiative for the rest of the war.[47] Despite their success, Tanzanian commanders felt that the Battle of Lukaya had been waged disastrously; had the Ugandans and Libyans pushed through the town after occupying it, they could have retaken Masaka and driven the TPDF out of Uganda.[48] On 13 March Tanzanian Junior Minister of Defence Moses Nnauye and Musuguri met with veterans of the engagement to find out more about what happened.[43] Those who had retreated from the Libyans expressed that they were stressed and wanted to be given a month's leave from the front line. Nnauye told them the war was too important for this to be done, as it would be detrimental to the TPDF's operational capability.[49] The 201st Brigade was subsequently reorganised so that its ranks were no longer dominated by militiamen.[50]

Course of the war

Shortly after occupying Lukaya,[38] the TPDF launched Operation Dada Idi, and in the following days the 207th and 208th Brigades cleared the Kampala road and captured Mpigi.[19] Ugandan and Libyan troops fled away from the front line towards the capital.[38] Meanwhile, Ugandan opposition groups met in Moshi. They subsequently created the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) as a unified umbrella organisation and established a cabinet.[51] The successful formation of the UNLF government eased Tanzanian concerns about the aftermath of a seizure of the capital.[52] Despite his troops' failure at Lukaya, Gaddafi further reinforced Amin with large amounts of equipment and 2,000 members of the People's Militia. The personnel and materiel were brought into Entebbe's international airport in a regular airlift.[53]

In early April Tanzanian forces began to concentrate their efforts on weakening the Ugandan position in Kampala.[54] Tanzanian commanders had originally assumed that Amin would station the bulk of his forces in the capital, and their initial plans called for a direct attack on the city. But from the high ground in Mpigi they could see the heavy amount of Libyan air traffic over the Entebbe peninsula and a large contingent of Ugandan and Libyan soldiers.[52] Musuguri ordered the TPDF to secure the peninsula, and on 7 April the 208th Brigade captured it. Many Libyan soldiers tried to evacuate to Kampala but were intercepted and killed.[55] Tanzanian commanders then began preparing to attack Kampala. Nyerere requested that they leave the eastern road from the city leading to Jinja clear so Libyan troops could evacuate. He thought that by allowing them to escape, Libya could avoid humiliation and quietly withdraw from the war. Nyerere also feared that further conflict with Libyan troops would incite Afro-Arab tensions and invite armed belligerence of other Arab states. He sent a message to Gaddafi explaining his decision, saying that the Libyans could be airlifted out of Uganda unopposed from the airstrip in Jinja.[56] Most of them promptly vacated Kampala through the open corridor to Kenya and Ethiopia, where they were repatriated.[57] The TPDF advanced into Kampala on 10 April, taking it with minimal resistance.[57] Combat operations in Uganda continued until 3 June, when Tanzanian forces reached the Sudanese border and eliminated the last resistance.[58] The TPDF withdrew from the country in 1981.[59]

Legacy

The Battle of Lukaya was the largest engagement of the Uganda–Tanzania War.[60][61] Despite the PLO's overall involvement in the Ugandan war effort, Nyerere did not harbour any ill will towards the organisation, instead citing its isolation on the international stage as the reason for its closeness to Amin.[12] On 7 February 1981 Obote gave Musuguri two spears in honour of "his gallant action in the Battle of Lukaya".[62] Many years after the battle a large plaque was placed in Lukaya to commemorate the Libyan soldiers who were killed there.[37] In the 2000s the Ugandan Government established the Order of Lukaya to be awarded to Ugandan rebels or allied foreigners who participated in the battle.[63]

Notes

- ^ The Tanzanian state-run paper, News, later estimated that 2,000 Ugandan troops participated in the action.[17]

- ^ Tanzanian Lieutenant Colonel Ben Msuya reported that 2,500 Uganda Army troops encamped at Bukulula, a location north of Masaka, in preparation for the operation, and that his troops dislodged them over the course of three days, culminating in the seizure of Lukaya.[21]

- ^ According to journalist Baldwin Mzirai, the international media was led to believe that the initial Tanzanian retreat from Lukaya was not a rout but a deliberate strategic action.[26] Reuters reported on 11 March that Ugandan exiles in Nairobi stated that UNLF troops had conducted a "tactical retreat" from the town.[27] Radio Uganda declared that the Uganda Army was conducting a successful counteroffensive.[28]

- ^ Amin's son, Jaffar Rembo, claimed that "it was alleged" that Maliyamungu and Gowan had been bribed to provide the TPDF with information on Ugandan positions so they could be struck with precise artillery fire.[33]

- ^ The circumstances surrounding Sule's death were not initially clear. Major Bernard Rwehururu, commander of the Suicide Battalion in Sembabule, overheard conflicting radio reports that Sule had either been killed by enemy fire or had been crushed by one of his tanks. When Rwehururu asked for clarification, he was told that he should focus on his own affairs, and the radio in Lukaya was subsequently turned off.[22] When Kisuule could not determine Sule's whereabouts, he asked Amin to instruct soldiers to look for his corpse among the bodies brought back to Kampala. Amin later told him that Sule was found among them, his face crushed.[16] Amin's son, Jaffar Rembo, claimed that Sule was shot from behind in a "so-called 'friendly fire' " incident.[33] According to journalist Faustin Mugabe, other "insiders" have said that his death was "treacherous".[34] Lieutenant Muzamir Amule dismissed their claims and supported the assertion that Sule was crushed by one of his tanks, and that this was not understood until the day after the battle.[34] In contrast, researcher Richard J. Reid also stated that Sule was "apparently killed by his own mutinous troops".[35]

- ^ Journalist Timothy Kalyegira wrote that 3,113 Ugandan troops were captured at the battle and taken to Rwamrumba Prison in Bukoba, Tanzania.[41]

Citations

- ^ a b Honey, Martha (12 April 1979). "Ugandan Capital Captured". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Roberts 2017, p. 155.

- ^ Roberts 2017, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Roberts 2017, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b Roberts 2017, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 79.

- ^ Legum 1980, p. B 432.

- ^ a b c d Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 89.

- ^ Roberts 2017, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Rwehururu 2002, p. 124.

- ^ Seftel 2010, p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e f g Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Pollack 2004, p. 369.

- ^ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 32, 62.

- ^ a b Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lubega, Henry (25 May 2014). "Tanzanians found Amin men weak - Col Kisuule". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Tanzania Reports Bitter Uganda Battle". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 19 March 1979. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d "How Mbarara, Kampala fell to Tanzanian army". Daily Monitor. 27 April 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Lubega, Henry (3 May 2014). "Musuya: The Tanzanian general who ruled Uganda for three days". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Rwehururu 2002, p. 125.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Pollack 2004, p. 371.

- ^ a b Mzirai 1980, p. 68.

- ^ Mzirai 1980, p. 71.

- ^ "Invaders Reported Retreating in Uganda". International Herald Tribune. No. 29, 883. Reuters. 12 March 1979. p. 2.

- ^ "Tanzanian Force in Uganda Is Reported to Fall Back". The New York Times. 12 March 1979. p. 3A.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 91.

- ^ Museveni, Yoweri K. (7 May 2012). "Mogadishu: Museveni responds to Obbo". New Vision. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mzirai 1980, p. 72.

- ^ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b Amin, Jaffar Rembo (14 April 2013). "How Amin's commander betrayed Ugandan fighters to Tanzanians". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Mugabe, Faustin (20 December 2015). "How bar fight sparked the 1979 Uganda - Tanzania war". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reid 2017, p. 70.

- ^ a b Rwehururu 2002, p. 126.

- ^ a b Kato, Joshua (23 January 2014). "Katonga bridge, the jewel of the liberation". New Vision. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 94.

- ^ "Battle for Lukaya". Africa Research Bulletin. Vol. 16–17. 1979. pp. 5186–5187.

- ^ a b c "Tanzania, Uganda both claim victory". The Ottawa Journal. United Press International. 19 March 1979. p. 10. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kalyegira, Timothy (15 April 2009). "Uncertainty after Amin overthrow". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Singh 2012, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b Mzirai 1980, p. 69.

- ^ Singh 2012, p. 175.

- ^ Amin, Jaffar Remo (21 April 2013). "How Amin smuggled his family from Entebbe fire to Libya". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 34.

- ^ Thomas 2012, p. 230.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Mzirai 1980, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 92.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 117.

- ^ a b Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 121.

- ^ Pollack 2004, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Pollack 2004, p. 372.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b Pollack 2004, p. 373.

- ^ Roberts 2017, p. 163.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Mzirai 1980, p. 67.

- ^ The Army Quarterly and Defence Journal. Vol. 109. 1979. p. 374. ISSN 0004-2552.

- ^ "Ugandan honour for Tanzanian COS". Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa. No. 6612–6661. 1981. OCLC 378680447.

- ^ Musinguzi, John (24 February 2013). "Understanding Museveni's medals". The Observer. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

References

- Avirgan, Tony; Honey, Martha (1983). War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House. ISBN 978-9976-1-0056-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cooper, Tom; Fontanellaz, Adrien (2015). Wars and Insurgencies of Uganda 1971–1994. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910294-55-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Legum, Colin, ed. (1980). Africa Contemporary Record: Annual Survey and Documents: 1978–1979. Vol. XI. New York: Africana Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8419-0160-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mzirai, Baldwin (1980). Kuzama kwa Idi Amin (in Swahili). Dar es Salaam: Publicity International. OCLC 9084117.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pollack, Kenneth Michael (2004). Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0686-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reid, Richard J. (2017). A History of Modern Uganda. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06720-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roberts, George (2017). "The Uganda–Tanzania War, the fall of Idi Amin, and the failure of African diplomacy, 1978–1979". In Anderson, David M.; Rolandsen, Øystein H. (eds.). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. London: Routledge. pp. 154–171. ISBN 978-1-317-53952-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rwehururu, Bernard (2002). Cross to the Gun. Kampala: Monitor. OCLC 50243051.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Seftel, Adam, ed. (2010) [1st pub. 1994]. Uganda: The Bloodstained Pearl of Africa and Its Struggle for Peace. From the Pages of Drum. Kampala: Fountain Publishers. ISBN 978-9970-02-036-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Singh, Madanjeet (2012). Culture of the Sepulchre: Idi Amin's Monster Regime. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-670-08573-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Charles Girard (2012). The Tanzanian People's Defence Force: An Exercise in Nation-building (PhD). University of Texas.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)