Cyclone Taylor

| Cyclone Taylor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hockey Hall of Fame, 1947 | |||

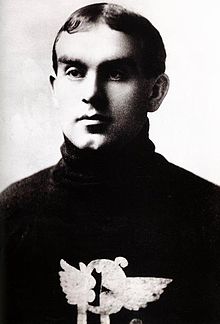

Taylor with the Ottawa Senators in 1908 | |||

| Born |

June 23, 1884 Tara, Ontario, Canada | ||

| Died |

June 9, 1979 (aged 94) Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada | ||

| Height | 5 ft 8 in (173 cm) | ||

| Weight | 165 lb (75 kg; 11 st 11 lb) | ||

| Position |

Rover Cover-point | ||

| Shot | Left | ||

| Played for |

Vancouver Maroons (PCHA) Vancouver Millionaires (PCHA) Renfrew Creamery Kings (NHA) Ottawa Hockey Club (ECAHA) Pittsburgh Athletic Club (WPHL) Portage Lakes Hockey Club (IHL) | ||

| Playing career | 1906–1922 | ||

Frederick Wellington "Cyclone" Taylor, MBE, (June 23, 1884 – June 9, 1979) was a Canadian professional ice hockey player and civil servant. Playing as a cover-point and rover, he played professionally for the Portage Lakes Hockey Club, the Renfrew Creamery Kings, the Ottawa Hockey Club and the Vancouver Millionaires from 1906 to 1922. Acknowledged as one of the first stars of hockey, Taylor was recognised as one of the fastest skaters and one of the most prolific scorers of his era. He won five scoring championships in the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA), and won the Stanley Cup twice, once in 1909 with Ottawa and again in 1915 with Vancouver. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1947.

Born and raised in Southern Ontario, Taylor moved to Manitoba in 1906 to play hockey. He quickly moved to Houghton, Michigan and spent two years in the International Hockey League, the first openly professional hockey league in the world. Returning to Canada in 1907 he joined the Senators, playing for them for two seasons. In 1909 he signed with Renfrew, becoming the highest paid athlete in the world on a per-game basis, before moving to Vancouver in 1912, finishing his career in 1922.

Upon moving to Ottawa in 1907 Taylor was given a position within the federal Interior Department as an immigration clerk, and maintained a position throughout his hockey career and after. In 1914 Taylor was the first Canadian official to board the Komagata Maru, a major incident relating to Canadian immigration. Rising to Commissioner of Immigration for British Columbia and the Yukon, the top position in the region, Taylor was named a Member of the Order of the British Empire in 1946 for his services in immigration, and retired in 1950.

Early life

Frederick Wellington Taylor was born in Tara, Ontario, the second son and fourth of five children to Archie and Mary Taylor.[a] The exact date of Taylor's birth is uncertain, though most sources give it as June 23, 1884.[1][b] Archie, the son of Scottish immigrants, was a travelling salesman who sold farm equipment.[2] Mary stayed at home and raised the children. Taylor was close to his mother, a devout Methodist, and took after her in never smoking, drinking, or swearing.[3] Taylor was named Frederick Wellington after a local veterinarian, who was a friend of Archie; Taylor's biographer Eric Whitehead states that on the day of Taylor's birth the two men were fishing, so Archie decided to name his son after the elder Frederick.[4] At the age of six, Taylor moved with his family to Listowel, a town 80 kilometres (50 mi) south of Tara.[5] The Taylor family lived a modest lifestyle in Listowel: Archie initially made around C$50–60 a month, which was not a lot to raise five children on.[6] To help the family out Taylor left school when he was 17 and started working in a local piano factory, earning around $20 a month, supplementing Archie's salary, which had risen to $75 a month.[7]

Though he had first skated at the age of five on ponds near Tara, it was in Listowel that Taylor first learned to play hockey.[8] He was given his first pair of skates and taught by a local barber named Jack Riggs, who was known in the community for his speed skating.[9] He joined an organized team, the Listowel Mintos, in 1897 when he was 13, and would spend the next five years with them; though initially a couple of years younger than the other players, Taylor was one of the most skilled on his team.[10] The Mintos joined the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA), the governing body of hockey in Ontario, for the 1900–01 season; playing in a local league organized by the OHA, the Mintos won the championship, with Taylor playing a major role.[11] They would reach the provincial junior championship in 1904, losing sudden-death overtime; this greatly enhanced Taylor's name across the province, and several teams were interested in having him join them.[12]

Taylor was reportedly invited in October 1903 by Bill Hewitt, the secretary of the OHA, to move to Toronto and play for the Toronto Marlboros. Happy with his life in Listowel, where he had his family and job, Taylor turned down the offer. This angered Hewitt, who had expected Taylor to accept his invitation and move cities. He thus banned Taylor from playing hockey in Ontario for the 1903–04 season, as he had the authority to sanction players, and did not want his offers refused.[13][c] Taylor did leave Listowel in 1904 and tried to join a team in Thessalon, however as player transfers were regulated by the OHA (ostensibly to keep players from moving from team to team and to preserve the ideals of amateurism), he was not sanctioned to play in Thessalon. Rather than play for any other team, Taylor sat out the season.[14]

Hockey career

Portage la Prairie and Portage Lakes (1906–1907)

Frustrated with sitting out a whole season of hockey, Taylor looked for other options for the upcoming season.[15] He moved west in early January 1906 and joined a team in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba for 1905–06; this was a pragmatic choice for Taylor, as the OHA had no jurisdiction in Manitoba.[16] As hockey was strictly amateur in Canada at the time, Taylor was offered room, board and $25 a month in spending money to join the team.[17] In his first game with Portage la Prairie Taylor scored two goals, impressing his opponents with his skilled play.[15] After one match against the Kenora Thistles, the top team in the league, Taylor was offered a chance to join them as they travelled east to challenge for the Stanley Cup, the championship trophy of Canadian hockey.[14] While considering the offer Taylor was also approached by representatives from the Portage Lakes Hockey Club, a professional team based in Houghton, Michigan that played in the International Hockey League (IHL), the first openly professional hockey league.[d][18][19] Offered US$400 to join the team, plus expenses, Taylor agreed.[20] It was not Taylor's first time playing in Houghton: in the 1902–03 season he had been invited to join a few friends studying dentistry there to play a series of exhibition games against local teams.[21]

In early February Taylor left Portage la Prairie, having played four games.[14] Playing cover-point (an early version of a defenceman), Taylor scored eleven goals in six games for Portage Lakes as the team won the Portage won the 1906 league championship.[22] The following season saw Taylor score 14 goals in 23 games as Portage Lakes repeated as league champions.[23] A rough and physical league, Taylor would recall his time in the IHL with fondness, noting that the "league was a wonderful testing and training ground, and [he] was a far better player for my experience there." He also found the atmosphere nice, as "[t]here was a different feeling there with the sport seemingly so far from its home and us all down from Canada as sort of paid mercenaries."[24]

Offering high salaries, the IHL brought in many of the top Canadian players, who were happy to be paid to play hockey for the first time in their careers (though some had been covertly paid in Canada). However the high wages were unsustainable, and with the decision of the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association (ECAHA), the top league in Canada, to allow professional players in 1907, the IHL folded that summer, allowing the players to return to Canada.[25] Taylor returned to Listowel for the summer of 1907, playing lacrosse and listening to offers to join various hockey teams for the upcoming season.[26] Representatives from the Quebec Bulldogs, Montreal Victorias, Montreal Wanderers, and Cobalt Silver Kings all met with Taylor. Cobalt's offer was the most interesting to Taylor largely due to their wealthy owner, Michael John O'Brien, a rail-builder and mine-owner, though he turned them down as they did not offer enough money.[27]

Ottawa Senators (1907–1909)

"In Portage La Prairie they called him a tornado, in Houghton, Michigan, he was known as a whirlwind. From now on he'll be known as Cyclone Taylor."

Allegedly written by Malcolm Brice, reporter for the Ottawa Free Press, after hearing the Earl Grey, Governor General of Canada refer to Taylor as a "cyclone" in reference to his skating ability.[28][e]

Taylor decided to sign with the Ottawa Senators, who played in the ECAHA (the league would soon become known as the ECHA, dropping the word "Amateur").[26] The Senators offered him a salary of $500 for the season, a high salary for the time but not extravagant.[29] What attracted Taylor to Ottawa was that the club also promised him a job within the immigration branch of the federal Department of the Interior; "the chance that it could turn into a permanent career job," as Whitehead wrote, was important to Taylor, and a career in the civil service promised job security for him after his hockey career ended.[30] He thus took up a position as a junior clerk for $35 a month.[31]

Soon after arriving in Ottawa, Taylor receive offers to leave the Senators and join different teams. The Ottawa Victorias, who played in the Federal Amateur Hockey League, a rival to the ECAHA, asked Taylor to play a two-game series against the Renfrew Creamery Kings of the local Upper Ottawa Valley Hockey League, with the possibility of a full-season contract.[32] Renfrew, owned by O'Brien, challenged the offer, however after the series ended and made their own offer to Taylor: $1500 for the season. They argued that as Taylor had not signed a contract with Ottawa he was free to leave. Taylor visited Renfrew, about 80 kilometres (50 mi) from Ottawa, and initially agreed to sign there as he heard rumours that he was not wanted in Ottawa.[33] However representatives from the Senators met up with Taylor and confirmed the club did want him, so he returned for the start of the season.[34]

The first game of the season saw Taylor play at centre for the Senators. As one of the main forwards and one of the fastest players in hockey, Taylor was constantly offside, as rules at the time did not allow players to pass the puck ahead of themselves and he was too quick for his linemates. It was decided then that he would be moved to cover-point for the rest of the season, as he would be further back on the ice and able to better utilize his speed.[35] Later on in the season, during a January 11, 1908 match against the Montreal Wanderers, the Earl Grey, Governor General of Canada, was said to have attended the game, and afterwards was overheard by Malcolm Brice, a reporter for the Ottawa Free Press, saying "That new No. 4, Taylor, he's a cyclone if ever I saw one," a reference to Taylor's speed. Though previously referenced as both a "tornado" and a "whirlwind", the "Cyclone" moniker remained for the rest of Taylor's career.[e] Taylor performed well in his first season with Ottawa, scoring nine goals in ten games and being named the best cover-point in the ECAHA.[36] After the season ended the Senators travelled to New York City for a series of exhibition matches against the Wanderers, with Taylor garnering the most press attention with his plays.[37]

At the start of the 1908–09 season, Taylor signed with the Pittsburgh Athletic Club of the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League.[38] However, after three games there he was released along with Fred Lake; both were accused of trying to undermine the team's management and of intentionally losing a game to do so.[39] Taylor considered offers from other teams but decided to return to Ottawa for the season, playing 11 games and scoring 9 goals. The Senators won the league championship and were awarded the Stanley Cup as a result.[40]

Renfrew Creamery Kings (1909–1912)

In the lead-up to the 1909–10 season Taylor was again courted by O'Brien to join his team in Renfrew. Throughout November 1909 there were contradictory newspaper reports about with whom Taylor would sign, with both Ottawa and Renfrew each claiming he had signed with them.[41][42] By December 30 an agreement was finalized with Renfrew. The salary was reported to be as high as $5,250 for the season, which would have made Taylor the highest-paid athlete in Canadian history. A comparison was made with baseball player Ty Cobb, who had signed around the same time for $6,500, though it was noted that baseball played 154 games in a season, while hockey only had 12; thus on a per-game basis Taylor was the highest-paid athlete in the world.[43][f]

The signing of Taylor was also important for O'Brien for a different reason. He had long sought to win the Stanley Cup, and previous efforts to challenge for it had been rebuffed, as were his efforts to join the Canadian Hockey Association (CHA), as the ECHA had re-constituted itself in November 1909.[44] He thus started a new league, the National Hockey Association (NHA), which was composed of teams refused entry to the CHA and new teams O'Brien owned.[45] By adding Taylor to the new league, the NHA gained immediate legitimacy, and the CHA would fold within a few weeks, its remaining teams admitted into the NHA.[46][47]

Aside from the high salary, Taylor was interested in joining Renfrew because they made it known they were trying to build a strong team, and were willing to pay for it. Shortly before he signed with the club, they had agreed to terms with the highly-sought brothers, Lester and Frank Patrick; approached by no fewer than six teams, they agreed to contacts for $3,000 and $2,000 respectively.[48] Other prominent players that joined the club were goaltender Bert Lindsay, and forward Herb Jordan, who agreed to turn professional when he signed with Renfrew.[49] The team was further bolstered when mid-way through the season Newsy Lalonde, one of the highest-scoring players of the era, was acquired.[50]

Despite the high-priced talent, with four future members of the Hockey Hall of Fame on the roster, Renfrew finished third in the NHA, and thus were not able to make a challenge for the Stanley Cup (only the league winner could do so). Taylor performed well, finishing fourth on the team in scoring with ten goals in twelve games.[51] During the season one of the most famous legends about Taylor developed: prior to Renfrew's first game in Ottawa against the Senators, Taylor boasted he would score a goal while skating backwards (at the time few players skated this way, let alone score goals while doing so). Despite his boast prior to the February 12, 1908 game, Taylor was held scoreless as Ottawa won 8–5.[52] However, during the next game between the two, on March 8 in Renfrew, the Millionaires won 17–2, and Taylor scored three times, including one where he skated backwards.[53]

Taylor re-signed with Renfrew for the 1910–11 season, though a league-wide drop in salaries saw him only make $1,800. Reflecting later on, Taylor said that he and the other players "knew those big first-year salaries couldn't last."[54] While the Patrick brothers had moved west to join their father to establish a lumber company in British Columbia, and Lalonde joining the rival Montreal Canadiens, Renfew again finished third.[55] Taylor scored twelve goals in sixteen games to again place fourth on the team in scoring.[51]

Renfrew disbanded prior to the 1911–12 season, and the rights to its players were dispersed to the other teams in the league. Taylor was claimed by the Wanderers, who were interested in him as the team owner, Sam Lichtenhein, was working on a new arena and needed a star player to bolster attendance. However Taylor was not interested in moving to, or playing in, Montreal, so refused to report to the club, stating he would only play for Ottawa, or not at all. Despite attempts by the Senators to trade for him, Taylor's rights remained with the Wanderers, and so he sat out the season.[56] Paid a salary of $1,200 by the Senators, in hopes that he would join them for the following season, Taylor spent the winter playing a few games in the local semi-professional league, and worked as a referee in the same league.[57] At the end of the season the NHA sent an all-star team to Vancouver, where the Patrick brothers had established a new professional league, the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA), for a series of games. Though Taylor had not played all year, the Patricks only accepted the games if Taylor was included on the NHA team. He played sparingly in the series, but was credited with drawing large crowds.[58]

Vancouver Millionaires (1912–1922)

Having moved out West in 1910, Lester and Frank Patrick worked with their father Joe in the lumber industry, though they sold the family business in 1911. Using the money from the sale the brothers set up the PCHA, and began to recruit players from Eastern Canada to join the league, which included the offer of the NHA all-star team to tour in 1912.[59]

After the conclusion of the 1911–12 season the Wanderers gave up trying to sign Taylor. He was offered a contract of $3,000 to join the Toronto Tecumsehs, double the salary of any other player, but turned it down saying he didn't like the idea of being bought and sold.[60] Ottawa also made an offer of $1,800 for the season, but again Taylor turned it down.[61] However he had been in frequent contact with the Patricks, who encouraged him to move West and play in their league.[62] After months of discussion, Taylor agreed to join the Vancouver Millionaires, with the decision announced on November 20. He was given a salary of $2,200, transportation back to Ottawa, and a four-month leave of absence from his immigration job.[63] This again made Taylor the highest-paid player in hockey, and was at least $500 more than anyone had earned in the PCHA the previous season.[64] As was his style, Taylor did not sign a contract, later stating that "never was in those days with the Patricks. It was just a verbal agreement, and we shook hands on it."[65] Speaking after the agreement, Lester Patrick noted that they "had Fred Taylor in mind right from the beginning. His acquisition was just a matter of timing."[66]

Much like he had for the NHA, Taylor's presence gave legitimacy to the PCHA: where the first games of the inaugural season saw only half the tickets sold, the Millionaires sold out their home opener for the 1912–13 season, Taylor's debut, the first sell-out for the PCHA.[67] Prior to that first game, against the New Westminster Royals on December 10, Taylor had severe stomach pains and nearly missed the match. He barely made it to the game, though he ended up scoring in a 7–2 Vancouver victory. However the stomach pain turned out to be appendicitis, which left Taylor severely ill during his first season in the West (he would wait until the season was over to have surgery).[68][69] Even so, he managed to play in all sixteen games for Vancouver during the season, finishing with ten goals and 8 assists (the PCHA was the first league to officially keep track of assists), fourth on his team and sixth overall in the league for scoring.[70]

The following season saw Taylor move positions to rover, a position that combined offence and defence, one he would play for the remainder of his career.[71] The change to a position that allowed for more offence saw Taylor lead the PCHA in scoring with 39 points in 16 games, tying with Tommy Dunderdale for the goal-scoring title with 24 each.[72] He repeated as the scoring leader in 1914–15, with 45 points in 16 games, and finished tied for second in goals scored with 23.[73] Vancouver finished first in the league and thus earned the right to compete for the Stanley Cup. Starting in 1914 the Cup had been competed for between the champions of the PCHA and the NHA, with each league hosting a best-of-five series in alternating years; the 1915 Final was held in Vancouver, and as the leagues used different rules games alternated between PCHA and NHA rules.[g] The NHA champions were the Ottawa Senators, who Taylor had played for previously and won the Cup with in 1909, and they placed all their focus on trying to contain him, to no avail.[74] Vancouver won the first three games to win the Cup, with Taylor scoring seven goals and three assists.[75]

Taylor repeated as PCHA scoring champion again in 1915–16 with 35 points in 18 games, finishing second for goals with 21 and tied for the lead in assists with 14, however Vancouver finished second in the league and thus was unable to defend their Stanley Cup title.[76] After the season ended Taylor announced his retirement, though this was not taken seriously by the league or his peers, and was largely ignored.[77] True enough, he was convinced to re-join the team prior to the start of the 1916–17 season.[78] He started the season strong, leading the league in scoring early on, but in early December his appendicitis flared up and he was forced to miss time and have surgery to remove his appendix.[79] Playing in 12 of the Millionaires' 23 games, Taylor still finished ninth overall in league scoring with 29 points, and third in assists with 15.[80]

Playing at full health for the 1917–18 season, Taylor finished first in goals (32) and points (43), and was second for assists (11) in 18 games, being named the most valuable player of the league.[81] Vancouver won the PCHA championship and travelled to Toronto to play the National Hockey League (NHL)[h] champion, the Toronto Arenas in the 1918 Stanley Cup Finals. Though Taylor scored the most goals in the series (9), and the Millionaires outscored the Arenas (21 to 18), Toronto won the best-of-five series, and thus the Cup.[82] Taylor repeated as scoring champion in 1918–19, and for the first time led in goals (23), assists (13), and points (36).[83] It marked the fifth and final time he would lead the PCHA in scoring.[84]

After the end of the 1918–19 season Taylor again announced his intent to retire, though he was back for the start of the 1919–20 season.[85] A leg injury forced him out of several games, and he only appeared in ten during the season, recording twelve points and finishing far behind the scoring leaders.[86] This contributed to a third retirement announcement, which he insisted was final.[87] However he was coaxed out of it by Frank Patrick, who ran the Millionaires, and played only in home games and then only as a replacement player.[i][88] He had five goals and one assist in the six games played, and the five games Vancouver played in the Stanley Cup Final against the Senators, recording one assist.[89] Ottawa won the Cup and Taylor decided that he was retiring yet again.[90] He sat out the 1921–22 season, but decided to attempt a return for the 1922–23 season, appearing with Vancouver, then known as the Maroons, against the Victoria Cougars on December 8, 1922.[91] However he was unable to keep pace any more, and after the one game decided to finally quit hockey.[92]

Life outside hockey

Immigration officer

Taylor had joined the Immigration Branch of the Department of the Interior in October 1907, a job that was arranged as an inducement to get Taylor to play with Ottawa.[30] Taylor liked the idea of a position within the federal government, seeing it as a position that would ensure job security after his hockey career ended.[30] He thus started out as a junior clerk, earning $35 a month.[31] When Taylor moved to Vancouver in 1912 he initially took a leave of absence from his position.[63] Frank Patrick would later use his close connection with Sir Richard McBride, the Premier of British Columbia, to get Taylor's position transferred west, and ultimately promoted to senior immigration inspector.[93]

By 1914 Taylor was in charge of overseeing traffic into the port of Vancouver, boarding ships and checking crew and passenger manifests.[94] It was in this capacity that Taylor was involved in the Komagata Maru incident. The Komagata Maru was a steamship of 376 Hindu, Muslim and Sikh immigrants from India that attempted to circumvent restrictive Canadian immigration laws. The ship reached Vancouver on May 23, 1914, and Taylor was the first immigration officer to board the ship.[95] Taylor would spend considerable time on the ship as it sat in the Vancouver harbour: with the passengers unable to disembark, Taylor took on the role of supervising everyone until it left back for India on July 23, the passengers refused entry into Canada.[96] Reflecting on the incident later in life, Taylor said "It was a terrible affair, and nobody was proud of it."[97]

When the First World War broke out in August 1914 Taylor enlisted in the Canadian Army.[97] Though reluctant to go overseas, he wanted to help out and was willing to do whatever was necessary. However shortly after his enlistment it was announced that immigration officials were deemed a vital job and exempt from service, so Taylor was discharged from the military and spent the war working in Vancouver.[98]

After he retired from hockey Taylor kept his immigration post, and eventually rose to become the Commissioner of Immigration for British Columbia and the Yukon, the top position in the region.[99] In 1946, Taylor was named as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for outstanding service to the country and community as an immigration officer in two wars. He retired from the civil service in 1950.[100]

Later career

Taylor remained involved in hockey after he stopped playing. He was inaugural president of the Pacific Coast Hockey League, serving from 1936 to 1940.[99] He dropped the puck in the ceremonial face-off that preceded the expansion Vancouver Canucks' first home game when the team joined the National Hockey League (NHL) in 1970. A season-ticket holder, Taylor was a fixture at Canucks games until his death.[101]

Taylor ran unsuccessfully for election, as a member of the B.C. Progressive Conservative party, in the Vancouver Centre riding in the 1952 British Columbia general election, where he finished fourth of six candidates.[102] He again ran in the Vancouver Centre riding in the 1953 British Columbia general election, where he had 1,007 votes for 5.27% of the ballots, and again finished fourth of six candidates.[103] In 1952 he was elected to one term as a member of the Vancouver Parks Board.[104]

Personal life

Raised a Methodist, Taylor never drank alcohol, smoked cigarettes, or cursed, which was unusual for hockey players. He attributed these values to his mother, who was religiously devout.[5] His family were staunch supporters of the federal Conservative Party, which proved a delicate situation when Taylor was offered a position in the Immigration Department upon his move to Ottawa, as the Liberal Party was in power at the time and the officers he met were all Liberals.[105] In the summer of 1908 Taylor helped found Scout troop No. 7 in Ottawa, starting a lifelong involvement with the Scouting movement.[106] In Vancouver he continued this work, and also took on an active role with the YMCA.[107] Known for his "way with words" and "admired for his easy, courtly manner," Taylor also was known to be well-dressed throughout his playing career.[108] Taylor is also reported to have been a Freemason.[109]

Taylor enjoyed other sports than hockey, and actively played lacrosse during the summers of his hockey career. While in Ottawa during the summer of 1908, he joined the Ottawa Capitals of the National Lacrosse Union. Taylor was seen as a good lacrosse player, though Whitehead has suggested that Taylor's abilities may have been embellished by reporters due to his fame from hockey.[110] Overall his time with the Capitals was uneventful, except for an incident during a game on June 27, 1908. Taylor got into a fight with a player and during the scuffle he accidentally punched the referee, Tom Carlind. Police immediately arrested Taylor and jailed him for several hours, until Carlind arrived and explained it was unintentional. League officials considered banning Taylor over the incident, however due to his ability to draw large crowds, they ultimately let him play the rest of the season.[111] He would later join the Vancouver Terminals in 1914, playing for $50 per game.[112]

Marriage and family

In February 1908 Taylor met Thirza Cook. A hockey fan, she worked as a secretary in the Immigration Department, and met Taylor there after watching him play the previous night.[113] After their first date Taylor met Cook's widowed mother, who was from a well-off family and related by marriage to John Rudolphus Booth, an Ottawa lumber tycoon. She was not impressed with Taylor, whose own background was of a lower social standing and did not like the idea of her daughter being with a hockey player, a feeling shared by Cook's six siblings (her father had worked in the Interior Department before his death).[114][115] Despite this animosity Taylor resolved to win the family over, and decided he would save $10,000 to prove his worth, a project that took him six years (at the time he was making a combined $2,800 between his two jobs).[116] While playing in Renfrew Taylor would take a train to Ottawa several times per week to visit Cook.[117] When he moved to Vancouver in 1912 he promised he would return for the spring and summer of 1913, initially planning for a wedding that autumn.[118] Taylor married Cook on March 19, 1914 at her Ottawa home, with Frank Patrick serving as the best man.[119] Their honeymoon saw them go to New York, where Taylor joined the Millionaires in an exhibition series; the couple would move to Vancouver after that, spending the rest of their lives there.[120] Thirza died in March 1963, from heart troubles.[121]

Taylor had five children: three sons and two daughters. John, the second oldest child, would also play hockey and won two Canadian university championships while attending the University of Toronto. Offered a contract by the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League, he turned it down on advice of his father and instead earned a law degree. John worked in immigration law before entering politics, and was elected to the House of Commons in 1957, representing Vancouver—Burrard until his defeat in the 1962 election.[122] A grandson, Mark Taylor, played in the NHL with the Philadelphia Flyers, Pittsburgh Penguins and Washington Capitals, from 1981 to 1986.[123] The oldest son, Fred Jr., opened a chain of sporting-goods stores, Cyclone Taylor Sports, and named them after his father.[124] Their youngest child, Joan, also predeceased Taylor, dying in 1976 from heart issues brought on from her figure skating career.[125] After breaking his hip in 1978, Taylor's health deteriorated and he died in his sleep in Vancouver on June 9, 1979.[126]

Legacy

Taylor was regarded as one of the best hockey players throughout his playing career, and was able to command attention and a high salary anywhere he went. In 1908 when he went to play in Pittsburgh, it was noted in the Pittsburgh Press how he was "in a position to get almost anything he asked for the coming season and there were lots of bidders," and that his signing in Pittsburgh was a great achievement for the team.[38] Likewise, when he left Ottawa in 1912 and moved to Vancouver, the Ottawa Citizen said he was "the greatest drawing card in the game" and that the Senators should have increased their salary offer to him.[61] Not noted for his physical stature (he was listed as being 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) and 165 pounds (75 kg) during his career, an average size for a hockey player in the era), he was more known for his speed and creativity than anything else.[127][128] His ability to draw crowds made him a valuable addition to any team, and in an era were players only signed on for one season at a time, Taylor always had several teams interested in his services, and thus was able to command some of the highest salaries of his time.[129][130]

In 1947 Taylor was elected into the Hockey Hall of Fame, and he would later be inducted into the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame and the British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame. When the Hockey Hall of Fame started construction on a new building in 1961, Taylor was given the honour to turn the sod.[71]

There are several awards named after Taylor. The Vancouver Canucks team award for most valuable player is named the Cyclone Taylor Trophy.[131] The Cyclone Taylor Cup was donated in 1966 and is the awarded to the winner of a tournament between the winners of the British Columbia Junior B leagues.[132] As well the junior Listowel Cyclones, based in Taylor's hometown, are named after him.[133]

Career statistics

| Regular season | Playoffs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Team | League | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | ||

| 1905–06 | Portage la Prairie | MHL | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1905–06 | Portage Lakes | IHL | 6 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1906–07 | Portage Lakes | IHL | 23 | 18 | 7 | 25 | 31 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1907–08 | Ottawa Senators | ECAHA | 10 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 40 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1908–09 | Pittsburgh PAC | WPHL | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1908–09 | Ottawa Senators | ECHA | 11 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 28 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1909–10 | Renfrew Creamery Kings | NHA | 13 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 19 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1910–11 | Renfrew Creamery Kings | NHA | 16 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 21 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1911–12 | NHA All-Stars | Exhib. | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1912–13 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 14 | 10 | 8 | 18 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1913–14 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 16 | 24 | 15 | 39 | 18 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1914–15 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 16 | 23 | 22 | 45 | 9 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1914–15 | Vancouver Millionaires | St-Cup | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 3 | ||

| 1915–16 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 18 | 22 | 13 | 35 | 9 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1916–17 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 12 | 14 | 15 | 29 | 12 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1917–18 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 18 | 32 | 11 | 43 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1917–18 | Vancouver Millionaires | St-Cup | — | — | — | — | — | 5 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 15 | ||

| 1918–19 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 20 | 23 | 13 | 36 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1919–20 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 10 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1920–21 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 6 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1920–21 | Vancouver Millionaires | St-Cup | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 1922–23 | Vancouver Maroons | PCHA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| NHA totals | 29 | 22 | 0 | 22 | 40 | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| PCHA totals | 130 | 159 | 104 | 263 | 65 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| St-Cup totals | — | — | — | — | — | 11 | 17 | 3 | 20 | 23 | ||||

- Source: Total Hockey[134]

References

Notes

- ^ The other children were, in order: Russell, Harriet, Elizabeth, and Rosella. See Whitehead 1977, p. 10.

- ^ Hockey historian Eric Zweig has noted there are discrepancies in various sources relating to Taylor's birth, with both 1884 and 1885 listed. He concludes that the 1884 dates is likely the correct one. See Zweig 2007, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Zweig has questioned this version of events, which was recounted by Taylor in the 1970s: Zweig notes that if the offer to join the Marlboros was made, it was likely in 1904, not 1903 when he was relatively unknown still. Zweig also questions how involved Hewitt, an executive of the OHA, would be with one of its teams. See Zweig 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Though ostensibly amateur, teams in Canada had started to covertly compensate players by this time, despite all leagues expressly forbidding such a practice. See Mason 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Despite claims by Whitehead that Brice wrote this, searches by hockey historians have found no such article. See Kitchen 2008, p. 160 and Zweig, p. 47.

- ^ The figure $5,250 comes from Whitehead's biography of Taylor. However Cosentino has suggested the base salary was closer to $2,000, with the rest coming from a guaranteed salary outside of hockey and a bond to ensure he would sign. Regardless, Taylor had the highest salary in hockey history. See Whitehead 1977, pp. 105–106 and Cosentino 1990, p. 73.

- ^ The most prominent difference in rules was that the PCHA still used the rover, while the NHA had abolished the position; thus PCHA games used seven players (six skaters and a goaltender) on each team, while the NHA used six.

- ^ The NHA has been replaced by the NHL as the top league in Eastern Canada starting in 1917–18.

- ^ At the time hockey players would play nearly the entire game without a break.

Citations

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 8

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 9–10

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 10–11

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 8–9

- ^ a b Whitehead 1977, p. 11

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 13–14

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 30–31

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 12

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 11–12

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 19–22

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 27

- ^ Zweig 2007, pp. 48–49

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 31

- ^ a b c Zweig 2007, p. 49

- ^ a b McKinley 2009, p. 41

- ^ McKinley 2000, p. 56

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 34

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 39

- ^ Mason 1998, p. 1

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 40

- ^ McKinley 2000, p. 55

- ^ McKinley 2000, p. 61

- ^ McKinley 2000, p. 64

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 52

- ^ Mason 1998, pp. 8–9

- ^ a b Kitchen 2008, p. 155

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 58

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 70

- ^ McKinley 2009, p. 58

- ^ a b c Whitehead 1980, p. 57

- ^ a b Whitehead 1980, p. 63

- ^ Kitchen 2008, pp. 156–157

- ^ Whitehead 1980, p. 67

- ^ Kitchen 2008, pp. 157–158

- ^ Whitehead 1980, p. 69

- ^ Whitehead 1980, p. 75

- ^ Whitehead 1980, p. 77

- ^ a b Pittsburgh Press Nov 11, 1908, p. 12.

- ^ Pittsburgh Press Nov 27, 1908, p. 22.

- ^ Kitchen 2008, pp. 161–162

- ^ Costentino 1990, pp. 62–73

- ^ Kitchen 2008, pp. 165–166

- ^ Costentino 1990, p. 73

- ^ Wong 2005, p. 50

- ^ Wong 2005, p. 51

- ^ Wong 2005, pp. 52–55

- ^ Cosentino 1990, p. 46

- ^ Cosentino 1990, p. 56

- ^ Cosentino 1990, p. 77

- ^ Cosentino 1990, p. 128

- ^ a b Cosentino 1990, p. 171

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 118–119

- ^ Ottawa Citizen Mar 9, 1910, p. 8.

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 126

- ^ McKinley 2009, p. 63

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 131–132

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 133

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 137–139

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, pp. 2–30

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 140

- ^ a b Ottawa Citizen Nov 21, 1912, p. 9.

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 36

- ^ a b Ottawa Citizen Nov 20, 1912, p. 9.

- ^ Whitehead 1980, p. 117

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 141

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 134

- ^ Wong 2005, p. 68

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 146–148

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 47

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 46

- ^ a b Shea 2012

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 61

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 78

- ^ Boslsby 2012, pp. 80–83

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 85

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 98

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 99

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 111

- ^ Boslsby 2012, pp. 112–113

- ^ Boslsby 2012, p. 115

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, pp. 129–130

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 136

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 145

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 144

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, pp. 148, 159

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, pp. 160–162

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 172

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 176

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 180

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, p. 190

- ^ Coleman 1964, p. 423

- ^ Bowlsby 2012, pp. 214–215

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 143, 156

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 157

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 159

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 160–162

- ^ a b Whitehead 1977, p. 163

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 164

- ^ a b Whitehead 1977, p. 185

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 193

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 200

- ^ Elections British Columbia 1988, p. 238

- ^ Elections British Columbia 1988, p. 252

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 194

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 57, 62

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 26

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 171

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 114

- ^ Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon

- ^ Whitehead 1980, p. 83

- ^ Whitehead 1980, pp. 84–85

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 158

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 71

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 72

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 150–151

- ^ Whitehead 1977, pp. 73, 100

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 117

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 142

- ^ Costentino 1990, p. 168

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 151

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 199

- ^ Hawthorn 2002, p. R15.

- ^ Hendriksen 2009

- ^ Cyclone Taylor Sports 2018

- ^ Whitehead 1977, p. 201

- ^ Ottawa Citizen Jun 11, 1979, p. 32.

- ^ Holzman & Nieforth 2002, p. 11

- ^ Coleman 1964, p. 661

- ^ McKinley 2009, pp. 59–60

- ^ Wong 2009, pp. 243–244

- ^ Maniago et al. 2018, p. 254

- ^ Cyclone Taylor Cup 2019

- ^ Listowel Cyclones 2019

- ^ Diamond 2002, p. 625

Bibliography

- Bowlsby, Craig H. (2012), Empire of Ice: The Rise and Fall of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, 1911–1926, Vancouver: Knights of Winter, ISBN 978-0-9691705-6-3

- Coleman, Charles L. (1964), The Trail of the Stanley Cup, Volume 1: 1893–1926 inc., Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing, ISBN 0-8403-2941-5

- Cosentino, Frank (1990), The Renfrew Millionaires: The Valley Boys of Winter 1910, Burnstown, Ontario: General Store Publishing House, ISBN 0-919431-35-6

- Cyclone Taylor Cup (2019), Cyclone Taylor Cup: About, Cyclone Taylor Cup, retrieved May 11, 2019

- Cyclone Taylor Sports (2018), About Us, Cyclone Taylor Sports, retrieved April 19, 2019

- Diamond, Dan, ed. (2002), Total Hockey: The Official Encyclopedia of the National Hockey League, Second Edition, New York: Total Sports Publishing, ISBN 1-892129-85-X

- Elections British Columbia (1988), Electoral History of British Columbia, 1871–1986, Victoria, BC: Queen's Printer for British Columbia, ISBN 0-7718-8677-2

- Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon, Fred "Cyclone" Taylor O.B.E., Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon, retrieved April 26, 2008

- Hawthorn, Tom (March 15, 2002), "John Taylor: Former MP famous for his 'footsteps' campaign", The Globe and Mail, Toronto

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hendriksen, Daniel (March 25, 2009), "Backchecking: Taylor Followed In Famous Grandfather's Footsteps", The Hockey News, Toronto, retrieved March 30, 2019

- Holzman, Morey; Nieforth, Joseph (2002), Deceptions and Doublecross: How the NHL Conquered Hockey, Toronto: Dundurn Press, ISBN 1-55002-413-2

- Kitchen, Paul (2008), Win, Tie, or Wrangle: The Inside Story of the Old Ottawa Senators 1883–1935, Manotick, Ontario: Penumbra Press, ISBN 978-1-897323-46-5

- Listowel Cyclones (2019), Fred Cyclone Taylor, Listowel Cyclones, retrieved May 11, 2019

- Maniago, Stephanie; De Vera, Alfred; Boddez, Ben; Brumwell, Chris; Brown, Ben, eds. (2018), 2018–19 Vancouver Canucks Media Guide, Vancouver: Hemlock Printers

- Mason, Daniel S. (Spring 1998), "The International Hockey League and the Professionalization of Ice Hockey, 1904–1907", Journal of Sport History, 25 (1): 1–17

- McKinley, Michael (2000), Putting a Roof on Winter: Hockey's Rise from Sport to Spectacle, Vancouver: Greystone Books, ISBN 1-55054-798-4

- McKinley, Michael (2009), Hockey: A People's History, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 978-0-7710-5771-7

- Ottawa Citizen (March 9, 1910), "Ottawa Team Meet Waterloo; Outclassed By Renfrew 17 to 2", Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa

- Ottawa Citizen (November 20, 1912), "Lichtenhein's War with Patricks Reacts as Boomerang on N.H.A.", Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa

- Ottawa Citizen (November 21, 1912), "Taylor Refuses to Jump Contract Will Leave for Coast Saturday", Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa

- Ottawa Citizen (June 11, 1979), "Hockey's Cyclone Taylor dies two weeks before 94th birthday", Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa

- Pittsburgh Press (November 11, 1908), "Fred Taylor to Play Here", Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh

- Pittsburgh Press (November 27, 1908), "Fred Taylor and Fred Lake Fired from P.A.C. Team of Hockey League", Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh

- Shea, Kevin (May 8, 2012), Spotlight: One on One with Cyclone Taylor, Hockey Hall of Fame, retrieved May 11, 2019

- Whitehead, Eric (1977), Cyclone Taylor: A Hockey Legend, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0-385-13063-5

- Whitehead, Eric (1980), The Patricks: Hockey's Royal Family, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0-385-15662-6

- Wong, John Chi-Kit (2009), "Boomtown Hockey: The Vancouver Millionaires", in Wong, John Chi-Kit (ed.), Coast to Coast: Hockey in Canada to the Second World War, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 223–257, ISBN 978-0-8020-9532-9

- Wong, John Chi-Kit (2005), Lords of the Rinks: The Emergence of the National Hockey League 1875–1936, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-8520-2

- Zweig, Eric (2007), "Setting Cyclone's Story Straight", Hockey Research Journal, 11: 47–50

External links

- Biographical information and career statistics from Eliteprospects.com, or Hockey-Reference.com, or Legends of Hockey, or The Internet Hockey Database

- 1884 births

- 1979 deaths

- British Columbia Conservative Party politicians

- Canadian Freemasons

- Canadian ice hockey players

- Canadian lacrosse players

- Canadian Members of the Order of the British Empire

- Canadian Methodists

- Canadian people of Scottish descent

- Canadian sportsperson-politicians

- Candidates in British Columbia provincial elections

- Hockey Hall of Fame inductees

- Ice hockey people from Ontario

- Ottawa Senators (NHA) players

- Ottawa Senators (original) players

- People from Bruce County

- Pittsburgh Athletic Club (ice hockey) players

- Portage Lakes Hockey Club players

- Renfrew Hockey Club players

- Scouting and Guiding in Canada

- Stanley Cup champions

- Vancouver Maroons players

- Vancouver Millionaires players