John Neal (writer)

John Neal Esq. | |

|---|---|

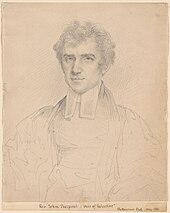

Portrait of John Neal by Sarah Miriam Peale, c. 1823 | |

| Born | August 25, 1793 Portland, Maine, United States |

| Died | June 20, 1876 (aged 82) Portland, Maine, United States |

| Resting place | Western Cemetery Portland, Maine, United States |

| Pen name | Somebody, M.D.C. &c. &c. &c. Jehu O'Cataract John O'Cataract Carter Holmes A New Englander Over-Sea |

| Occupation | Writer, critic, editor, activist, lawyer, lecturer, entrepreneur |

| Signature | |

John Neal (August 25, 1793 – June 20, 1876) was an American writer, critic, editor, lecturer, and activist. Considered both eccentric and influential, he delivered speeches and wrote magazine essays, novels, poems, and short stories between the 1810s and 1870s in the US and Great Britain, championing American literary nationalism and regionalism in their earliest stages. Neal advanced the development of American art, advocated for early feminist causes, advocated the end of slavery and racism, and helped establish the gymnastics movement in the US.

A pioneer of colloquialism and natural diction, John Neal is the first author to use "son-of-a-bitch" in a work of fiction.[1] He attained his greatest literary achievements between 1817 and 1835,[2] during which time he was central to American literature's evolution from the British influences dominant in works of founding American authors James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving, whom he derided, to the new voices of American Renaissance authors Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Walt Whitman, all of whom he influenced.[3] His feminist advocacy advanced the ideas of predecessors Mary Wollstonecraft, Catharine Macaulay, and Judith Sargent Murray while laying groundwork for successors Sarah Moore Grimké, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Margaret Fuller.

Neal lived all but eighteen years of his life in Portland, Maine, though a large proportion of his life’s work he achieved between his early twenties and early thirties in Baltimore, Maryland, and London, England. In Baltimore he founded his law and literary careers and in London he became the first American to be published in British literary journals.[4] A largely self-educated man, he attended no schools after the age of twelve, though he passed the bar exam to start practicing law in his early twenties and was awarded an honorary masters degree in his early forties. Neal's work history includes varied employment and self-employment before pursuit of a career as an author and attorney, simultaneous careers that lasted sixty and forty years, respectively. By old age Neal had earned comfortable wealth and community standing through varied business investments, arts patronage, and civic leadership.

Received by his contemporaries and remembered by historians as an uncontrolled genius, he was classified for generations as a secondary transitional figure in American literary history, though twenty-first century scholarship has reassessed his work and influence in light of earlier historians’ prejudices. Despite a formidable list of historically superlative achievements, John Neal is an author without a masterpiece.[5] Rachel Dyer is considered his best novel,[6] “Otter-Bag, the Oneida Chief” and “David Whicher” his best short stories,[7] and The Yankee his most influential periodical creation.[8]

Biography

Early life 1793–1815

- Childhood and education

John Neal and his twin sister Rachel were born in Portland, Maine on August 25, 1793, the only children of parents John Neal and Rachel Hall Neal.[9] The senior John Neal, a school teacher, died a month after their birth, after which the senior Rachel Neal set up her own school, took in boarders, and relied on assistance from the siblings’ unmarried uncle James Neal and others in their Quaker community.[10] Aside from attending his mother’s school, Neal also spent two years at a Quaker boarding school in neighboring Windham before attending public school in Portland.[10] In his autobiography, Neal recalls his lifelong struggle with a short temper and quarrelsome reputation as originating in public school, at which he was physically abused by his schoolmaster, Stephen Patten, and bullied by his classmates[11] until he “resolved one day...to be badgered and bullied no longer...and I kept my resolution, till I was no longer a boy...I have kept the field against all comers, from that day to this.”[12][a] Neal’s schooling ended at the age of twelve.[11]

- (Self-)Employment

Neal’s employment as an adolescent and teenager exposed him to dishonest business practices and taught him lessons in salesmanship. In his first two jobs in Portland dry goods shops, he learned to use his appearance of youthful innocence to pass off counterfeit bills[b] on unsuspecting customers and misrepresent the quality of merchandise.[11] Neal was laid off at both business when they failed, leading Neal to join an itinerant penmanship instructor with whom he taught twelve-lesson courses for $5[c] to students at Bowdoin College in nearby Brunswick.[19] Eventually striking out on his own as a penmanship instructor, he added miniature portraiture[20] and $3[d] portrait sketches to his repertoire of services and amassed a savings of $200[e] over a short period by plying his business on the people of Hallowell, Augusta, Waterville, and Norridgewock, Maine.[19] Still a teenager in 1809, he answered an ad for employment with a dry goods shop in Boston, Massachusetts and moved to the larger city.[21]

In Boston he once again achieved successful self-employment, this time exploiting supply chain constrictions caused by the War of 1812 to make quick profits smuggling goods between Boston, Massachusetts and Baltimore, Maryland.[21] It was in Boston in 1814 that he met and established a business partnership with poet/lawyer John Pierpont and Pierpont’s brother in-law Joseph Lord.[9] The three partners established stores in Boston, Baltimore, and Charleston, South Carolina[9] before the recession following the War of 1812 upended the firm and left Pierpont and Neal bankrupt in Baltimore in 1815.[21] Though the “Pierpont, Lord, and Neal” dry goods store chain proved to be short-lived, Neal’s relationship with Pierpont grew into the closest and longest-lived friendship[f] of his life.[9]

Neal’s experience going into business full-time in Portland, Maine at the age of twelve and riding out the multiple economic booms and busts that eventually left him in Baltimore at age twenty-two made him a proud and ambitious young man who viewed reliance on his own talents and resources as the key to his recovery and future success.[22]

Baltimore 1815–1823

Bankrupt with a failed business,[g] John Neal took to writing, first as a hobby, then as a means to pay expenses while studying law.[25]

- Studying law

Aside from a political essay in the Hallowell (Maine) Gazette when he was a teenager, the first venue to publish Neal’s work was The Portico in 1816, a literary journal that began in January of that year and published regularly through June 1818.[26] His poems, essays, and literary criticism quickly established Neal as its second-most prolific[27] – albeit unpaid[28] – contributor, and eventually led him to take over as editor.[29] In 1816, Neal joined with the journal’s founder, Dr. Tobias Watkins, Pierpont, and four other men to co-found the Delphian Club, a social group that was closely associated with the journal.[27] Neal also wrote for The Port Folio magazine in 1816.[30]

Like many other American writers in the early nineteenth century, Neal juggled vocations and income sources like law practice, print translation, editing, and teaching to survive and build a career.[31] While writing his earliest poetry, novels, and essays he was simultaneously engaged in independent law study as an apprentice in the office of William H. Winder, a fellow Delphian.[32] Neal’s output during his time in Baltimore was particularly prodigious, earning him the moniker of “Jehu O’Cataract” from his Delphian Club associates.[33] To put his pen to work, Neal “began to cast about for something better to do—something, at least, that would pay better; and, after considering the matter for ten minutes or so, determined to try [his] hand at a novel.”[34] Fewer than seventy novels had been published by Americans and few of those had met with financial success.[35] Neal was nevertheless inspired by Pierpont’s 1816 financial success with “The Airs of Palestine” and encouraged by the reception of his initial submissions to The Portico. He resolved that “there was nothing left for me but authorship, or starvation, if I persisted in my plan of studying law.[36] This was in spite of the fact that the US in 1816 “had not more than half a dozen authors; and of these, only Washington Irving had received more than enough to pay for the salt in his porridge.”[37]

Neal went to work in the summer of 1816 to write his first novel, Keep Cool,[h] which went to print in 1817 and earned him $200.[38][i] The next year he published his first collection of poetry, Battle of Niagara, a Poem, without Notes; and Goldau, or the Maniac Harper,[j] for which he was paid $100[k] in-kind in books. The same year Hezekiah Niles hired him for the arduous job of creating an index for six years of weekly publications of his Weekly Register magazine.[38] Neal recalled the indexing job as “about the dreariest and heaviest drudgery mortal man was ever tried with,” on which he labored sixteen hours a day, seven days a week, for more than four months, taking additional time each day to work on “Battle of Niagara” and “Goldau.”[40] Niles called it "the most laborious work of the kind that ever appeared in any country."[41] Niles sold copies for $3[l] and paid Neal $200, plus a bound copy of the magazine collection he indexed, which itself was valued at $100.[38] In 1819 Neal earned $100 with the publication of Otho: a Tragedy, in Five Acts[38] and took a job as editor of the Federal Republican and Baltimore Telegraph.[42] He also took over work that year from fellow Delphian Paul Allen, getting paid by the page to fulfill chapter subscriptions for Allen’s History of the American Revolution that Allen was unable to fulfill.[38] Neal's contribution accounts for about three quarters of the book.[43] By these means Neal was able to pay his expenses while studying law, then subsequently pass the bar, and start practicing law in Baltimore in 1820.[44]

- Practicing lawyer

Neal’s final years in Baltimore were his most productive as a novelist. He published Logan, A Family History in 1822. In 1823 he published three novels: Seventy-Six, Randolph, and Errata; or, the Works of Will. Adams. Not only did he write and publish novels faster in this period than any other in his life, but the public reception of Seventy-Six propelled him to a status as James Fenimore Cooper’s chief rival as the leading American novelist.[45]

Randolph served as a vehicle for multiple insults against prominent lawyer William Pinkney, which the Baltimore law community may have overlooked but for the fact that Pinkney died while the novel was at the printers. Rather than retract the insults, Neal added a footnote reinforcing his decision to let the comments stand despite Pinkney’s death. His outraged son, Edward Coote Pinkney, challenged Neal to a duel. Having established himself six years earlier as an outspoken opponent of dueling,[m] Neal refused. Pinkney posted a broadside calling out Neal as a coward and Neal reprinted it, along with his own snide remarks, in an “Editorial Notice” in the final pages of Errata.[47]

John Neal’s last four years (1820-1823) in Baltimore became socially turbulent in other ways. When other members of the Delphian Club rejected his nomination for a new member, he quit suddenly in January 1820, against the urging of his closest friend, John Pierpont.[48] Neal had long ago become disillusioned with his Quaker upbringing, but the Society of Friends formally excommunicated him in September on the basis of physical violence after his participation in a street brawl.[49] In this period he also quickly became disillusioned with law practice, reflecting later that he had already become “weary of the law—weary as death...For many years [he] had been at war, open war, with the whole tribe of lawyers in America.”[50]

This pattern was to follow him through subsequent stages in life. According to historians Edward Watts and David J. Carlson, “Ironically...at precisely the moment when he was endeavoring to establish himself as the American writer, Neal was also alienating friends, critics, and the general public at an alarming rate.”[51]

As a result of controversies and social alienations, Neal was emotionally ready to leave Baltimore by the fall of 1823.[52] The final catalyst for his departure, and the one that decided for him where he would go next, was a dinner party in late November with an English friend who quoted Sydney Smith’s 1820 then-notorious remark, “in the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?”[53] Neal remembered in his autobiography,

I know not what I said in reply; but I know how I felt...I told him...that I would answer that question from over sea; that I would leave my office, my library, and my law-business, and take passage in the first vessel I could find...and see what might be done... I might do something, so American, as to secure the attention of Englishmen.[54]

Whether it had more to do with Smith or Pinkney, Neal took less than a month after that dinner date to settle his affairs in Baltimore and secure passage on a ship bound for England on December 15, 1823.[55]

England 1824–1827

If John Neal’s reasons for leaving Baltimore were social, his reasons for choosing London as his temporary residence were both altruistic and economic. The relocation figured into three professional goals that guided him through the 1820s: to supplant Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper as the leading American literary voice, to bring about a new distinctly American literary style, and to reverse the British literary establishment’s disdain for American writers.[56] He followed Irving’s precedent of using temporary residence in London to exploit England’s larger literary market and, thus, simultaneously achieve greater legitimacy at home in the United States.[57] The connection to Irving was literal, for he traveled to London carrying a letter of introduction to a friend of Irving’s and rented the same rooms Irving formerly occupied while writing The Sketch Book only a few years earlier.[58]

For writers in the early nineteenth century, being London-based at the time of a work’s publication led to benefits that included greater royalties than could be earned in the US, a higher quality print format, and more attention by reviewers.[59] Seventy-Six and Logan had already been pirated by London publishers before his arrival without any money being paid to him, an economic disenfranchisement he hoped to correct by bringing Errata and Randolph for publication in-person by those companies.[60]

- Writing for Blackwood’s

Neal arrived in Liverpool on January 8, 1824 carrying the unfinished manuscript for his next novel Brother Jonathan, copies of his earlier books, and enough money to spend a few months sightseeing on his way to London.[61] He was initially unconcerned about his prospects, feeling that, “happen what would, if people gave any thing [sic] for books here, they would not be able to starve me, since I could live upon air, and write faster than any man that ever lived.”[62] But by early April, London publishers’ continued refusal to pay him to republish either of his two books they had not yet pirated forced Neal to seek publication in magazines.[63] His financial situation had become increasingly desperate[64] when he received a letter from William Blackwood of Blackwood’s Magazine on April 20 stating, “You are exactly the correspondent that we want...and I hope you will continue to favor us with your communications, and you may depend upon being liberally treated.”[65] Included was a bank draft for five guineas[n] – more than five times what Neal had expected to be paid.[65] For the next year and a half, Neal would make his living writing for Blackwood’s.

John Neal’s essay in Blackwood’s on the 1824 candidates for president was the first article by an American to appear in a British literary journal[68] and was quoted and republished widely throughout Europe.[64] Being “a journal that took pleasure in self-conscious play with pseudonym, puffery, and scurrilous critique,”[69] Neal’s sensational, off-hand style was a great fit for the magazine and he quickly became its most featured author.[70] His greatest contribution was the “American Writers” series that critiqued 100 authors (including himself) in alphabetical order under the pen name Carter Holmes, an English traveler persona with supposed extensive experience in the United States.[33] This series represents the first history ever written of American literature.[71]

Neal felt that the pen name was necessary “to bring together...two great nations;” to achieve this he “must write as an Englishman, or, at least, not as an American; being careful to say the truth, and always to acknowledge the faults of others, and especially of my countrymen.”[72] Blackwood’s also became a platform for his earliest written works on gender and women’s rights, the first of which attracted the attention of Joanna Baillie[o] in October 1824.[73] The articles declared intellectual equality of men and women, critiqued gendered social relations, and called for women’s suffrage.[74]

After thirty-six letters and fifteen months under the name Carter Holmes, Neal revealed himself to Blackwood in his request to have William Blackwood and Sons publish Brother Jonathan.[75] Though Blackwood did agree to publish Brother Jonathan in 1825, the back-and-forth over manuscript revisions soured the relationship and Neal was sent adrift in London once again with no source of income.[76]

- Living with Bentham

After his break with William Blackwood in autumn of 1825, Neal spent a short time earning much less than what he earned at Blackwood’s[77] writing articles for other papers, including the European Magazine, The London Magazine, the European Review, the Monthly Magazine, The New Monthly Magazine, and the Oriental Herald.[78] Through contacts made participating in the London Debating Society Neal received an invitation to a dinner party with seventy-seven year-old utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Bentham was so impressed with the thirty-two year-old John Neal that Bentham offered him rooms[p] at his Hermitage and a position as his personal secretary.[79] Neal spent the next year and a half writing for Bentham’s Westminster Review and through this association he recruited both Bentham and John Stuart Mill to the cause of women’s rights.[80]

In the spring of 1827 Neal asked Bentham to fund a trip to the United States. Bentham offered instead to finance Neal’s one-way passage as Bentham felt Neal could find a better home for his talent in the US.[81] Neal left England having caught the attention of the British literary elite and published the novel he brought with him, yet having failed to achieve international fame with the new great American novel, he was no longer Cooper’s chief American rival.[82] After a month-long trip to Paris, he left Europe in May 1827.

Portland, Maine 1827–1876

- Opposition to return

John Neal arrived in New York harbor in June 1827 intending to restart his law career and break into the magazine editing business.[83] Before settling in, he made a visit to his mother and twin sister in his native Portland, Maine. He was surprised to be met with vocal opposition from community members who were offended by his derision of prominent Portlanders in the semi-autobiographical Errata,[q] by the way he depicted New England dialect and habits in Brother Jonathan, and his criticism of American writers in Blackwood’s Magazine.[84] Among the more vocal critics of Neal’s "American Writers" series in Blackwood’s was a young William Lloyd Garrison, who, writing as an apprentice at the Newburyport Herald in Massachusetts in 1825, said “We cannot express sufficiently, our Indignation at this renegade’s base attempt to assassinate the reputation of this country”[86]

Maine residents upset with Neal posted derogatory broadsides in Brunswick[r] and in Portland.[87] The Portland Broadside read:

Dr. Jones was a derogatory nickname given to a Black man whom the authors of the broadside hired to follow John Neal in public. Realizing that he was well paid, Neal gave the man consent to follow him for as long as he was employed to do so, which lasted for days until the racist joke became too old and expensive for the orchestrators to continue.[88] Other manifestations of displeasure with Neal’s visit resulted in verbally and physically violent exchanges in the streets.[89]

In characteristic contrarian style, Neal’s reaction to this vocal opposition was to settle in Portland instead of New York. As he remembers it himself, “Verily, verily,' said I, 'if they take that position, here I will stay, till I am both rooted and grounded—grounded in the graveyard, if nowhere else.”[90] He had already sent for his law library to be shipped to New York, so he ordered it redirected to Portland while he secured an office on Exchange Street and applied for admission to the bar. John Neal assumed his position as Portland, Maine’s most famous author[91] and made short order of establishing himself as an accepted member of his community.

- Gymnastics pioneer

One of Neal’s early efforts in Portland was to open a gymnasium[s] later in 1827 using Friedrich Jahn's Turnen model he learned from German refugee Carl Voelker in London.[93] While still in England in 1826, Neal published articles on gymnastics in the new American Journal of Education and urged Thomas Jefferson to include a gymnastics school at the University of Virginia.[94]

Neal is the first American founder of a public gymnasium in the United States,[t][97] at which he taught boxing, fencing, and other gymnastics activities to his students, including his cousin, Neal Dow.[98] The gym had an all-White membership, many of whom identified with the abolition movement. In the spring of 1828, all but two other members[u] rejected new Black members Neal sponsored to join; the racist decision caused disillusionment in Neal, and he left the gym shortly thereafter.[100] The same year he started gymnasiums in nearby Saco and at Bowdoin College in Brunswick.[101]

- Magazines and fiction

In January 1828 Neal established The Yankee monthly magazine with himself as editor, and continued publication through the end of 1829.[102] He used its pages to vindicate himself to fellow Portlanders,[103] critique American art[104] and drama,[105] host a discourse on the nature of New Englander identity,[106] and uplift new literary voices like John Greenleaf Whittier, Edgar Allan Poe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Nathaniel Hawthorne.[8]

Neal wrote for many other magazines, as well, between the late 1820s and the mid 1840s, including the The Token, Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer, Atlantic Souvenir, Mrs. Stephens’ Illustrated New Monthly, The New-England Magazine, Atkinson’s Casket, Emerson’s U.S. Magazine, Portland Sketch Book, Portland Magazine, New-York Mirror, Godey’s Lady’s Book, The Ladies’ Companion, The Family Companion and Ladies’ Mirror, The Pioneer, and The Colombian Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine. Between the mid 1830s and late 1840s he served short stints as editor of New-England Galaxy, The New World, Brother Jonathan (the journal with the same name as his 1825 novel), and Portland Transcript.[107]

After his return from England, Neal had given up on writing the great American novel and instead focused his new fiction efforts on short stories. Though he published Rachel Dyer in 1828, Authorship[v] in 1830, and The Down-Easters in 1833, these novels were all reworkings of writing done in England.[7] Tales like “Otter-Bag, the Oneida Chief” (1829), “The Haunted Man” (1832), “David Whicher” (1832), and “The Squatter” (1835) played a pivotal role in shaping the relatively new short story genre between the late 1820s and the mid 1830s.[108] Rachel Dyer is his most successful fictional work and his most readable novel to a modern audience.[6] As the first bound hardcover novel to fictionalize the Salem witch trials,[109] it inspired the use of witchcraft in multiple poems and stories by John Greenleaf Whittier. Nathaniel Hawthorne noted Rachel Dyer's influence on his novel The Scarlet Letter.[110]

- Eccentric community member

The height of Neal’s involvement with American magazines also overlaps with his stint as a traveling lecturer between 1829 and 1848.[111] Aside from these travels, Neal’s life after returning from England became increasingly focused on his local community, particularly after he inherited a granite quarry business following his uncle James Neal’s death in 1832. Biographer Windsor Daggett considered his October 1828 wedding to be the watershed moment, such that "although he continued to be a writer and an editor, his life from that date belongs essentially to his family and to the city of Portland."[112] Biographer Donald A. Sears draws the line twelve years later, claiming that after 1840 Neal became increasingly occupied with real estate development, investments in the insurance industry, his inherited structural granite business, developing the new railroad connection to Montreal, and other business interests. No longer reliant on writing as a source of income, he turned his attention to patronizing the arts, pushing civic improvements,[x] uplifting artists and writers through constructive criticism, and active citizenship in Portland, Maine.[114] He retired from his law practice in 1860.[112]

Many of his literary contemporaries in larger cities and early historians mistook Neal’s change in focus as a disappearance. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in 1845: “How slowly our literature grows up! Most of our writers of promise have come to untimely ends. There was that wild fellow, John Neal, who almost turned my boyish brain with his romances; he surely has long been dead, else he never could keep himself so quiet.”[115] James Russell Lowell’s 1848 A Fable for Critics includes lines that make a similar statement about Neal’s alleged disappearance in Maine.

There swaggers John Neal who has wasted in Maine

The sinews and cords of his pugilist brain[116]

Neal’s local image as an eccentric socialite was captured by Fanny Appleton Longfellow, second wife of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, when she visited Portland, Maine in 1843: “John Neal gave me great amusement with his racy, head-over-heels speeches. His mind seems at the boiling-over point always and froths out at every pore of his face and tongue. Introduced a dozen people to me as one would mow grass.”[117] A decade earlier, his unique fashion sense and juggling of literary and athletic interests were described this way by a former law apprentice:

He was in a strange-shaped jacket, with a vest of his own form and fashion, for he has all things made according to his notions, dictating to tailors, furniture-makers, house-builders, book-binders, cooks and milliners also… He was over careful and very neat in his person, but not a fop or a dandy, for they follow fashions, and he sets all at defiance. Neal was then alternately talking with a lot of men who were boxing and fencing, for he was a boxing-master, and fencing-master too, and as a printer’s devil came in, crying “copy, more copy,” he would race with a huge swan’s quill, full gallop, over sheets of paper as with a steam-pen, and off went one page, and off went another, and then a lesson in boxing, the thump of glove to glove, then the mask, and the stamp of the sandal, and the ringing of the foils.[118]

Though John Neal quickly grew to be accepted by the Portland, Maine community despite initial signs of rejection in 1827, his last forty-nine years in his hometown were not without controversy. He had a long-standing feud with his cousin, “the mischief-making, meddlesome Neal Dow.”[119] Their tensions often played out as personal attacks in local periodicals as early as 1828, growing to its height in the early 1850s surrounding Neal’s attacks on the new Dow-authored and Dow-championed Maine prohibition law (the “hugest of humbugs”[120]), as well as his legal defense of an accused liquor seller being prosecuted under that law.[121] In response to Dow’s involvement as mayor in the Portland Rum Riot of 1855, Neal declared that his cousin should be hanged for murder, though eight years later when Dow was facing charges in Alabama for arming enslaved Black Americans as a Union Brigadier General during the Civil War, Neal called for Dow’s release at a Portland prayer meeting.[122] Neal nevertheless felt he “had been wronged and betrayed, year after year” and expressed in his 1869 autobiography that late in life they had still not come to good terms.[123]

Though Neal pursued romantic and sexual interests as a younger man in Baltimore, he did not start his own family until he returned to Portland, Maine. He married his cousin Eleanor Hall in October of 1828 and their first child Mary was born in December of the following year. Eleanor Hall Neal gave birth to four more children: James (1831), Margaret Eleanor (1834), Eleanor (1844), and John Pierpont (1847). Neal outlived two of those children: Eleanor who died in 1845 at 11 months of age and James who died in 1856 at twenty-five years of age. He also outlived his mother, Rachel Hall Neal, who died in 1849, and his twin sister Rachel Neal, who died in 1858. Neal raised his children in the house he built in 1836[y] on State Street of granite from his inherited quarry, which survived the great fire of 1866 that destroyed his office and library on Exchange Street.[125] Also in 1836 he received an honorary masters degree from Bowdoin College, the same institution at which Neal scraped together a living as a self-employed teenage penmanship instructor and that later educated the more economically privileged Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.[126]

At the urging of Longfellow and other friends, John Neal returned to novel writing in the 1850s, publishing True Womanhood in 1859.[127] His last books include an autobiography titled Wandering Recollections of a Somewhat Busy Life (1869), a collection of pieces for and about children titled Great Mysteries and Little Plagues (1870), and a guidebook for his hometown titled Portland Illustrated (1874).

By 1870 in his old age, he had amassed a comfortable fortune, valued at $80,000.[128][z] His last appearance in the public eye was likely an 1875 syndicated article from the Portland Advertiser, which an eighty-one year-old Neal physically overpowering a man in his early twenties who was smoking on a non-smoking streetcar.[130] Neal died on June 20, 1876, survived by his wife Eleanor Hall Neal and his children Mary Neal, Margaret Eleanor Neal, John Pierpont Neal.[131] He was buried in the Neal family plot in Portland, Maine's Western Cemetery.[132]

Writing

John Neal’s body of literary work spans almost sixty years from the end of the War of 1812 to a decade following the Civil War. His writing both reflects and challenges shifting American ways of life over those years,[133] though he achieved his major literary accomplishments between 1817 and 1835.[2] He started his career as an American reading public was just beginning to emerge,[134] working immediately and consistently within the nation's developing “complex web of print culture.”[135] His efforts to subvert the influence of the British literary elite[136] and to develop a rival American literature were largely credited to his successors until more recent twenty-first century scholarship.[137] John Neal is considered an influential American literary figure with no masterpiece of his own.[5]

Style

- Excessive Byronic Romanticism

In poetry and novels, John Neal was influenced more by Lord Byron that by any other preceding or contemporary literary figure.[138] In Neal's earliest published work of his Baltimore literary career,[aa] a 150-page critique of Byron printed in three installments of The Portico in 1817, Neal praised the Briton’s bold departure from contemporary expectations of literary moralism: "We get to approve crime, it is made so dazzlingly glorious by his magick."[139] Under Byronic influence and in defiance of his American predecessors/contemporaries Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, Neal used his early novels to depict dark, conflicted heroes of great intellect and morals who may not exhibit the physical strength and beauty normally associated with those personal qualities.[140] Displeased with his contemporaries’ use of rigid moralism and sentimentality, Neal felt that “faithful representations of native character...bring strangers acquainted with what we are most anxious to conceal...and...with our own peculiarities and our own faults.”[141]

Far from mimicking Byron, Neal’s brand of Romanticism also reflects his aversion for self-criticism and revision, relying instead on “nearly automatic writing”[142] that is aesthetically excessive to the point of challenging the reader’s ability to follow the story.[143] Though often read as Neal’s inability to control himself, this excessive and erratic version of Romantic writing has been recognized as a tool used intentionally by Neal to build his brand, enhance the commercial viability of his works, and craft a new American literature.[144][ab]

- American nationalism

In the era following the War of 1812, American writers and critics increasingly focused on the movement toward literary nationalism, but Neal felt their work fell short by relying on old British conventions of authorship to frame American phenomena.[146] Writing more than a decade after Neal first made these claims in print, James Fenimore Cooper voiced his mainstream sensibility, claiming it is “obvious that...the literature of England and that of America must be fashioned after the same models,” for Americans have a claim to “Milton, and Shakespeare, and all the old masters of the language.”[147]

In stark contrast to Cooper, Neal expressed the same year that “to succeed...[the American writer] must resemble nobody…[he] must be unlike all that have gone before [him]” and issue “another Declaration of Independence, in the great Republic of Letters.”[148] Neal set out to achieve this by using and convincing other writers to use peculiarly American characters, settings, historical events, and manners of speech in literature.[149]

Neal’s call for literary nationalism was economically driven as well. Dismissal of American writers by the British literary establishment in the 1810s and 1820s compelled Neal and others to constantly justify, promote, and assert their work in order to be read and paid.[150] Going further, Neal used magazine articles and prefaces to his novels to engage in a “caustic assault” on these British literary figures.[149] American writers like Neal and his successors imagined the English author as an aristocrat writing for personal amusement, in contrast to themselves as middle class professionals plying a commercial trade for sustenance.[151] By mimicking the common and sometimes profane language of his countrymen in fiction, Neal hoped to expand his appeal to a broader readership of minimally educated book buyers, thereby guaranteeing the existence of an American national literature by ensuring its economic viability.[152]

- Talking on paper

Key to Nealian literary nationalism is a device for narration and dialogue that he referred to as “talk[ing] on paper,”[153] or "natural writing."[85] As a pioneer of this American invention, Neal was “the first in America to be natural in his diction”[154] and his work represents “the first deviation from...Irvingesque graciousness.”[155] Contemporary critic Robert Carter told Neal after reading Randolph, “On every page are sentences which sound to me just as if you were talking them and I can picture myself your exact tone gesture and expression in uttering them.”[156]

Neal promoted this new style as more appropriate for American literature and also contrasted it with older British conventions for which he held vocal disdain. In the “Unpublished Preface” to Rachel Dyer, Neal declared,

I never shall write what is now worshipped under the name of classical English. It is no natural language—it never was—it never will be spoken alive on this earth: and therefore, ought never to be written. We have dead languages enough now; but the deadest language I ever met with or heard of, was that in use among the writers of Queen Anne’s day.[157]

- American regionalism

Starting in the late 1820s, Neal shifted his focus from nationalism to regionalism in response to the rise of Jacksonian populism in the US. This manifested as a shift in Neal's writing toward showcasing and contrasting coexisting regional and multicultural differences within the United States.

In particular, Neal used the essays and stories in his magazine The Yankee to make this point. Historian Kerin Holt found that the magazine “lays the groundwork for reading the nation itself as a collection of voices in conversation. In a nation where 'unity' itself is a polite fiction, The Yankee asks readers to decide for themselves how to manage the multiple and contending sides of a federal union.”[158]

Neal’s employment of regionalism was partly motivated by an imperative to preserve regional variations in American English that he viewed as disappearing.[159] In this spirit of preservation, he used colloquial, regional dialects in his writing and was one of the first American writers to do so.[110] This work was recognized almost 100 years later by the creators of the Dictionary of American English, who consulted Neal's novels Brother Jonathan, Rachel Dyer, and The Down-Easters.[160]

Literary criticism

John Neal was first published[ac] as the author of a 150-page critique of Lord Byron in The Portico in 1816, and he returned to literary criticism throughout his career.[26] He used criticism in magazines and prefaces to his novels to encourage desired changes in the field and to uplift new writers.

Many of the changes Neal sought could be included under the stylistic umbrella of American literary nationalism. He called for “faithful representations of native character”[141] in literature that utilize the “abundant and hidden sources of fertility in their own beautiful brave earth...in the northern, as well as the southern Americas.”[162]

- "American Writers"

Neal’s most formidable collection of literary criticism writing is the “American Writers” essay series he wrote for Blackwood’s Magazine while in England. Reviewing 100 authors (including himself) in alphabetical order, the series is remembered as the earliest written history of American literature[163] and was reprinted as a collection by Fred Lewis Pattee in 1937. In the preface, Pattee acknowledged this body of work as “the first American product strong enough to break into the British reviews” and “the first attempt anywhere at a history of American literature.”[164] Neal wrote that almost all of those 100 authors were mere copies of English predecessors, referring to Charles Brockden Brown, Washington Irving, and James Fenimore Cooper, respectively, as copies of William Godwin, Oliver Goldsmith, and Sir Walter Scott.”[165]

- Uplifting new writers

John Neal used his role as critic, particularly in the pages of his Portland, Maine-based magazine The Yankee, to draw attention to newer writers in whose work he saw promise. John Greenleaf Whittier, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow all received their first substantial sponsorship or praise in the magazine’s pages.[166] Neal held a high opinion of his own opinion, remarking in his 1869 autobiography that,

I could enumerate fifty or a hundred, perhaps, to whom I had foretold their destiny; no one of the whole having disappointed me at last. Among these were authors, poets, painters, actors, preachers, inventors, &c., all of whom, without a single exception, having become more or less distinguished. Of course, therefore, my opinion was thought worth having, and my predictions prophecy.[167]

The weight of Neal’s critical opinion is corroborated by Whittier himself, who, when submitting a poem for Neal’s criticism in 1828, included in the accompanying letter, “I have just written something for your consideration...if you don’t like it, say so privately; and I will quit poetry, and everything also of a literary nature, for I am sick at heart of the business.”[168]

- Discovering Poe

Of the encouraging words John Neal offered to emerging authors, the most historically impactful are those directed to Edgar Allan Poe, who likely dropped poetry in favor of short stories based on Neal’s critiques.[169] By the time he published his third volume he had not yet met with enthusiasm from anybody but John Neal.[170] Their first interaction was in late summer of 1829, when Poe submitted a poem for review, which Neal published in the September issue of The Yankee, saying “If E. A. P. of Baltimore—whose lines about Heaven...are, though nonsense, rather exquisite...might make a beautiful and perhaps magnificent poem. There is a good deal here to justify such a hope.”[171]

Having received the initial critique, Poe submitted next excerpts from “Al Aaraaf” and “Tamerlane” with an accompanying letter claiming the September review to be “the very first words of encouragement I ever remember to have heard”[172] and that “I am young—not yet twenty—am a poet—if deep worship of all beauty can make me one...I would give the world to embody one half the ideas afloat in my imagination.”[173] Neal’s review of these works was more glowing than the first:

He is entirely a stranger to us; but with all their faults, if the remainder of Al Aaraaf and Tamerlane is as good, as the body of the extracts here given—to say nothing of the more extraordinary parts, he will to deserve to stand high—very high—in the estimation of the shining brotherhood.[173]

Poe expressed his desire to acknowledge his first champion by dedicating his next volume, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems, to Neal, but the critic assured Poe that Neal’s mixed reputation would be an injury to both poet and the volume. Poe instead applied the dedication to only the individual poem “Tamerlane.”[174]

After Poe’s death, Neal defended him against attacks in Rufus Wilmot Griswold’s unsympathetic obituary of Poe, writing in 1850 that Poe “saw farther, and looked more steadily, and more inquisitively into the elements of darkness—into the shadowy, the shifting and the mysterious—than did most of the shining brotherhood about him.”[175] In the same article for the Portland Advertiser he attacked Griswold as “a Rhadamanthus, who is not to be bilked of his fee, a thimble-full of newspaper notoriety.”[175] Griswold’s response not only questioned Neal’s relationship with Poe but also attacked his standing in the literary community, saying that Neal “had never had even the slightest personal acquaintance with Poe in his life, [yet] rushes from a sleep which the public had trusted was eternal, to declare that my characterization of Poe...is false and malicious.”[176]

Art criticism

John Neal first ventured into art criticism within his 1823 novel Randolph.[177][ad] Though he continued work in this field at least as late 1869, his chief impact and involvement outside his immediate geographic sphere was in the 1820s.[178] Randolph, which Neal advertised as “a story in the form of letters, giving an account of our celebrities, orators, writers, painters, &c., &c.,”[179] is based on his experience with the Peale family of Baltimore, and later earned him recognition as America’s first art critic.[180] Neal around this time accessed Rembrandt Peale’s art museum, courted his daughter Rosalba Carriera Peale, and sat for portraits with his niece Sarah Miriam Peale.[181]

Though Neal’s role as an art critic at this time was overshadowed by his other vocations in literature and law, he was the first American to critique art effectively.[182] Historian Harold Edward Dickson put it this way: “As much as for the artist lore he recorded, it is for the vigor and originality of his delivery and for his having written when he did that Neal deserves some consideration as a forerunner of the ‘American Vasari.’”[182] Though he has received this recognition in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Neal’s impact was already being overlooked as early as 1834 in William Dunlap’s History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, which makes no mention of Neal or the direct predecessor to Dunlap’s work, Neal’s 1829 essay “Landscape and Portrait-Painting” in The Yankee.[183]

Toward the middle of the century, after he had accumulated sufficient wealth and influence in his hometown of Portland, Maine, Neal turned more of his attention toward patronizing and uplifting artists in his immediate area, including Charles Codman and Benjamin Paul Akers.[184] Neal met Akers when he was asked by a common acquaintance to assess Akers's early works of clay sculpture. Seeing promise, Neal offered him studio space above his office and commissioned his first bust. Neal’s encouragement, patronage, and connections helped Akers to become steadily employed with bust commissions.[185] Neal claims a similar place in the life of Codman, who received his first informed criticism from Neal. The two first met when Codman was a sign-maker. Neal offered guidance and contacts sufficient for Codman to graduate from a struggling trades painter seeking odd jobs to an established, patronized fine art landscape painter.[186] Neal also helped guide the work and careers of Franklin Simmons, John Rollin Tilton, and Harrison Bird Brown.[187] Bird became Portland's most successful artist of the nineteenth century.[188]

- Taste and approach

John Neal’s earliest approach to critiquing art in the early 1820s was largely based on intuition, though he also was influenced by August Wilhelm Schlegel’s Course of Lectures in Dramatic Art and Literature, first published in English in the US in 1815.[189] Revealing his lack of training, Neal in the 1860s remembered his work in the 1820s: “I had been scribbling in the papers about Rembrandt Peale’s gallery, and criticizing some of the pictures, from sheer instinct and without any knowledge of painting.”[190] His confidence in this approach is evident in his use of the novel Randolph to explore art viewers’ abilities to arrive at critical judgements without the ability to explain those judgements.[104] This earliest example of Neal’s art criticism also shows Neal’s disdain for connoisseurship, which he sees as intertwined with an aristocratic way of life incompatible with American democratic ideals.[191]

Neal’s residence in London (1824–1827) and trip to Paris (1827) considerably broadened his exposure to the works of masters and to theoretical bases for art criticism.[192] Initially he shows the influence of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Discourses, but his Blackwood’s articles (1824–1825) showed him breaking with those tenets by favoring landscapes over history painting and focusing more on trades painting.[193] Reynolds’s approach would remain dominant in England and the US until John Ruskin’s Modern Painters in 1843, though Neal’s 1829 “Landscape and Portrait-Painting” article in The Yankee anticipated many of those Ruskinesque changes by distinguishing between "things seen by the artist" and "things as they are."[194]

Comparatively constant is Neal’s taste for bold, unlabored approaches to painting that utilize "an offhand, free, sketchy style, without high finish."[195] The same could be said of what Dickson described as Neal’s “fantastic mixture of common sense and absurdity, of intelligent observation and dross” that portrays Neal the art critic as “melodramatic, addicted to exaggeration, superficial, inconsistent, ill-informed, naive.”[104] These descriptors apply less to his last essays on art, a two-part series in The Atlantic Monthly in 1868 and 1869 that conspicuously lack the qualities of Neal's boastful, confident, and passionate style in the 1820s.[196]

Poetry

The bulk of John Neal’s poetry was published in The Portico while studying law in Baltimore. His only bound collection of poems is Battle of Niagara, A Poem, without Notes; and Goldau, or the Maniac Harper, published in 1818 under Neal’s Delphian Club name Jehu O’Cataract. It was republished the next year as Battle of Niagara. Second Edition Enlarged, with Other Poems under his real name. Though “Battle of Niagara” brought him little fame or money, it is considered the best poetic description of Niagara Falls up to that time.[197] Poems by Neal are also featured in Specimens of American Poetry edited by Samuel Kettell (1829), The Poets and Poetry of America edited by Rufus Wilmot Griswold (1850), and American Poetry from the Beginning to Whitman edited by Louis Untermeyer (1931).

Drama

John Neal authored two plays, neither of which were ever produced on stage: Otho: A Tragedy, in Five Acts and Our Ephraim, or The New Englanders, A What-d’ye-call-it?—in three Acts.

Otho, written in verse and heavily inspired by the works of Lord Byron, sold for $100[ae] and was published in 1819.[198] Neal’s closest friend, John Pierpont, warned of the density and obscurity of the script, telling him in a letter that it needed “a sky-light or two” cut into it.[199] Biographer Donald A. Sears described the plot as “at once both mystifying and trite.”[161] Neal brought the script with him to London with plans to revise it and have it produced for the stage while he was there (1824–1827), but he never achieved this goal.[200]

"Not knowin', can't say."

— John Neal, Our Ephraim, 1834[201]

Our Ephraim was commissioned by actor James Henry Hackett in 1834, asking Neal in a letter to “squat right down & in your ready style in two or three days conjure me together something ‘curious nice.’”[202] He promised Neal $50[af] up front, plus $50 if the play was successful enough for three performances and an additional $100 if it ran for six.[203] Hackett rejected the play upon receipt as unsuitable for production: too many roles requiring rural Maine accents, unrealistic set requirements, and too much scheduled improvisation.[204] Biographer Benjamin Lease nevertheless regards Our Ephraim as “a significant advance in early American theatrical realism.”[205] As editor of The New-England Galaxy in 1835, Neal published the play in five installments between May and June of that year.[206]

- Theatrical criticism

Neal’s most noteworthy work of theatrical criticism is a five-installment essay “The Drama” published in the August 1829 issue of his magazine The Yankee. Complaining of what he saw as stilted dialogue in contemporary theatre, Neal contended that “when a person talks beautifully in his sorrow, it shows both great preparation and insincerity“ and urged that playwrights should, “avoid poetry whenever the characters are much in earnest.”[207] Sixty years later William Dean Howells was considered innovative for saying the same thing.[208]

Short stories

John Neal played a pivotal role in developing the relatively new genre of the short story between the late 1820s and the mid 1830s, though he continued publishing in this genre through the middle of the following decade.[108] This is a period in John Neal’s career when the poor reception of Brother Jonathan (1825) led him to give up on authoring the great American novel, publishing no new novels excepting reworkings of manuscripts he wrote in England (1824-1827) between that time and the publication of True Womanhood in 1859.[7] Neal also began to rely less on writing as a source of income after receiving an inheritance from his uncle James Neal in 1832 and shifting more of his attention to a wider web of investments and business interests in Portland, Maine.[2]

Lease considers “Otter-Bag, the Oneida Chief” and “David Whicher”, published in The Token in 1829 and 1832 respectively, as his best short stories,[7] though “The Haunted Man” (1832) also gets special recognition as the first work of fiction to use psychotherapy as a basis for a story.[210] Lease claims that the two stories “overshadow the less inspired efforts of his more famous contemporaries and add a dimension to the art of storytelling not to be found in Irving and Poe, rarely in Hawthorne, and rarely in American fiction until Melville and Twain decades later (and Faulkner a century later) began telling their tales.”[7] Ironically, “David Whicher” was published anonymously and authorship was not attributed to Neal until the 1960s.[108]

Like his magazine essays and lectures, Neal’s stories in this period challenged new socio-political phenomena that grew in the period leading up to and including Andrew Jackson’s terms as US president (1829-1837): continental nationhood, empire building, Indian removal, consolidation of federal power, citizenship increasingly connected to race, and restrictions on women imposed by the Cult of Domesticity.[211] “David Whicher” in particular challenged a body of popular literature that converged in the 1820s around a “divisive and destructive insistence on frontiersman and the Indian as implacable enemies.”[212] Neal wrote "David Whicher" particularly in response to “The Indian Fighter” by Timothy Flint, reprinted in the same magazine two years earlier.[213] His stories in this period also used humor and satire to address social and political phenomena, most notably "Courtship" (1829), "The Utilitarian" (1830), "The Young Phrenologist" (1836), "Animal Magnetism" (1839), and "The Ins and the Outs" (1841).[214]

Novels

With the exception of True Womanhood (published 1859), John Neal published all of his novels between 1817 and 1833. The first four he wrote and published in Baltimore, Maryland: Keep Cool (1817), Logan (1822), Seventy-Six (1823), Randolph (1823), and Errata (1823). He wrote Brother Jonathan in Baltimore, but revised and published it in England in 1825. He published Rachel Dyer (1828), Authorship[ag] (1830), and The Down-Easters (1833) while living in Portland, Maine, but they are all reworkings of content he largely wrote while in England.[7]

- Keep Cool

Neal remembered in his autobiography that “In writing [Keep Cool], I had two objects in view: one was to discourage dueling: and another was — I forget what.”[215] Perhaps greater than his moral message, this novel made Neal “the first in American to be natural in his diction”[154] and the “father of American subversive fiction.”[216] But as Sears commented on this first novel, “The gulf between Neal’s prophetic vision of a native literature and his own capacity to fulfill that vision is painfully apparent.”[217] And yet, the impact of his attempt was great on future American novelists. As Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in 1845, thinking of his college days reading Neal's early novels, “there was that wild fellow, John Neal, who almost turned my boyish brain with his romances.”[115]

"It was there," said he, "there exactly where that horse is passing now, that they first fired upon me. I set off at a speed up that hill, but, finding nine of the party there, I determined to dash over that elevation in front; I attempted it, but shot after shot was fired after me, until I preferred making one desperate attempt, sword in hand, to being shot down, like a fat goose, upon a broken gallop. I wheeled, made a dead set at the son-of-a-bitch in my rear, unhorsed him, and actually broke through the line."

— John Neal, Seventy-Six, 1823[218]

- Seventy-Six

Being one of Neal’s most readable novels to a modern audience, Seventy-Six was republished by facsimile in 1971 – only the second time since 1840[ah] that one of his novels had been republished.[219] When originally released in 1823, Neal was at the height of his prominence, being at the time the chief rival of leading American author, James Fenimore Cooper.[45] Inspired by Cooper’s The Spy, Neal had shared his manuscript for Seventy-Six with him, requesting his criticism and assistance before publication.[220] Neal based the story on historical research compiled a few years earlier while helping his friend Paul Allen complete his History of the American Revolution.[38] Seventy-Six was criticized at the time for its use of profanity and is recognized today as being the first work of American fiction to use the phrase “son-of-a-bitch.”[1]

- Randolph

Randolph (1823) includes the earliest of Neal's art criticism and contributes to his historical reputation as America’s first art critic.[221] Neal communicated his opinions on art through the thin veil of the novel's protagonist, who "criticized every thing [sic] he read and saw" and "had something to say of every person he met—our orators, statesmen, lawyers, authors, poets, and painters."[43] Like many of his other novels, Randolph was quickly praised for its innovation and criticized for its erratic, unintelligible style. Both views are expressed in a contemporary letter from sixteen year-old Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to his mother:

You mention “Seventy Six” and “Randolph.” If you call the former of these “over-wought” [sic] I do not know what you will say of the latter. Of Randolph… It seems to me...to be a compound of reason and nonsense—drollery and absurdity—wit and nastiness… And still I believe there are parts of it that go far to prove it the work of Genius.[222]

- Rachel Dyer

Rachel Dyer: a North American Story (1828) is widely considered to be John Neal’s most successful fictional work and his most readable novel to a modern audience.[6] When it was republished by facsimile in 1964, this was the first time since 1840 that any of Neal's books had been republished. Along with Brother Jonathan and The Down-Easters, it portrays a remarkable amount of peculiar American folkways, accents, and slang and was referenced about 100 years later by the compilers of the Dictionary of American English.[160] Like many of John Neal’s early novels, it is a historical fiction, this one being set during the Salem witch trials. Rachel Dyer was the first hardcover novelized version of this story, preceded only by Salem, an Eastern Tale, a largely unnoticed 1820 serial novel by an unknown author published in a New York City magazine. Rachel Dyer influenced the use of witchcraft in multiple poems and stories by John Greenleaf Whittier and in Nathaniel Hawthorne's novels The Scarlet Letter and The House of Seven Gables.[223]

Magazine editorship

| Title | Period | Headquarters |

|---|---|---|

| The Portico | Final issue: June, 1818 | Baltimore, MD |

| Federal Republican and Baltimore Telegraph | February — July, 1819 | Baltimore, MD |

| The Yankee | January, 1828 — August 13, 1828 | Portland, ME |

| The Yankee and Boston Literary Gazette | August 20, 1828 — December, 1829 | Boston, MA |

| The New-England Galaxy | January — December, 1835 | Boston, MA |

| The New World | January — April, 1840 | New York, NY |

| Brother Jonathan | May — December, 1843 | New York, NY |

| Portland Transcript | June 10 — July 8, 1848 | Portland, ME |

- Baltimore magazines

John Neal’s first two positions as a magazine editor came to him through connections made at the Delphian Club in Baltimore. The editor of The Portico, Dr. Tobias Watkins, was also president of the Delphians, and asked Neal to fill in as editor of the June 1818 issue when he was appointed assistant Surgeon General of the United States. Because of circumstances outside Neal’s control, this turned out to be the last issue.[29] His position at the Federal Republican and Baltimore Telegraph was also a fill-in, this one for fellow Delphian Paul Allen, whom Neal and Watkins helped that same year to fill subscription chapters for his History of the American Revolution.[38]

- The Yankee

Neal’s longest stint as magazine editor was for The Yankee, which he founded in January 1828 only a few months after returning to his native Portland, Maine from his stay in London. It ran under that name until, for financial reasons, it merged with a Boston paper and took on the name The Yankee and Boston Literary Gazette starting with the August 20, 1828 issue.[158] It ceased publication at the end of 1828, at which time it merged with the New-England Galaxy.[225]

Despite the professed allegiance to Benthamian Utilitarianism on its cover and frontispiece, Neal more significantly used his magazine to reinforce the standing of his hometown and of Northern New England on the national stage, arguing both for the region’s merit and for an appreciation of the qualities that differentiate the regions of the US.[226] Reacting to expectations that a literary journal such as this ought to be headquartered in a larger city, Neal wrote, “We mean to publish in Portland. Whatever the people of New-York, or Boston or Philadelphia or Baltimore might say, Portland is the place for us.”[227]

The sense of American regionalism that John Neal painted in the pages of The Yankee was distinct from that of regionalists to come after him later in the century, “who tended to portray regional spaces in nostalgic or sentimental terms as ‘enclaves of tradition’ that were posed against an increasingly urban and industrial nation,” according to historian David J. Carlson. Instead, “Neal remained committed to imagining regions as dynamic, future-oriented spaces whose identities would—and should—remain elusive."[228] He pursued this goal by publishing profiles of New Englanders and New England lifeways by others in direct conflict with his own, often posing them in conversation with each other in the magazine’s pages.[229]

According to Sears, however, The Yankee’s greatest impact was uplifting new literary voices such as John Greenleaf Whittier, Edgar Allan Poe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Nathaniel Hawthorne.[8]

- Post-Yankee editorship

Neal’s editorship of magazines put him in relationship with other major American literary figures of his time. As editor of The New-England Galaxy in 1835, he published an early story by twenty-five year-old Margaret Fuller, and the two would become better acquainted later in the decade when she hired him to lecture for students at her Providence, Rhode Island school and to a party to discuss phrenology, animal magnetism, and clairvoyance.[230] As editor of Brother Jonathan in 1843 he worked with Seba Smith, Elizabeth Oakes Smith, and Nathaniel Parker Willis, all of whom knew Neal from their time in Portland, though they were at the time living in New York City.[231] One of the magazine’s staff writers Neal knew well was Walt Whitman, then in his mid twenties.[232] Neal used Brother Jonathan to publish a serial Novella, Ruth Elder.[231]

Lecturing

Between 1829 and 1848 Neal supplemented his income as a lecturer. Traveling on the lyceum circuit he spoke on topics such as “literature, eloquence, the fine arts, political economy, temperance, poets and poetry, public-speaking, our pilgrim-fathers, colonization, law and lawyers, the study of languages, natural-history, phrenology, women’s-rights, self-education, self-reliance, and self-distrust, progress of opinion, &c., &c., &c.”[233] His first lecture was in February 1829, on the topic of temperance at a meeting of the Portland Association for the Promotion of Temperance in Portland, Maine at the First Parish Church. His last was titled “Man” and was held at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island in September 1848.[234] All but a few of these lectures were written in advance and published afterward to reach a wider audience.[111]

In the years following the February 1829 temperance lecture, Neal was invited to lecture on various topics before groups hosted by institutions such as Colby College in Waterville, Maine and the Maine Charitable Mechanics Association in Portland.[111] Like his first (limited) public speaking experience with the debating society in Baltimore in 1823, in which he simultaneously attacked the legal bases for Black American enslavement and denial of women’s rights,[235] his first public speech on women’s rights after returning from England was spontaneous. He was asked on the spot to address a crowd on the subject of freedom at Portland’s Second Parish Church on Independence Day 1832. Neal accepted and gave an unprepared speech using the subjects of freedom and the Independence Day holiday to attack contemporary institutions as affronts to freedom: enslavement of Black Americans, denial of women’s rights to property ownership under coverture, and denial of women’s suffrage as taxation without representation – the foundation of American independence from England.[236]

After the Independence Day 1832 speech, women’s rights became a favorite topic of his frequent lecture engagements between 1832 and 1843 in places like Portland, Maine; Boston, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; and New York, New York. Because they were almost always published afterward and often covered in newspaper reviews, these events broadened Neal’s sphere of influence and made his ideas more accessible to readers not necessarily aligned with his views.[237] His oratory style was described by Margaret Fuller in 1837: “Mr. Neal does not argue quite fairly, he uses reason while it lasts, and then, if he gets into a scrape, helps himself out by wit, by sentiment or strings of assertions. But if I had him by myself I think I could drive him to the wall.” Despite this “exaggeration and coxcombry,” though, she admired his “magnetic genius,” “lion heart,” and “sense of the ludicrous.”[238]

His most well-attended address was titled “Rights of Women” at New York’s City’s largest auditorium at the time, the Broadway Tabernacle, part of a lecture series sponsored by the Mechanics’ Library Association. Held on January 24, 1843, it was attended by an estimated 3,000 people and was widely covered in the periodicals like the New-York Tribune and New York Herald.[239]

Activism

Using magazine articles, short stories, novels, public speaking, political organizing, and personal relationships, John Neal acted throughout his adult life on issues like dueling, temperance, slavery, racism, feminism, and women’s rights.

Dueling

The first socio-political issue to elicit action from John Neal in the public sphere is dueling, which was the subject of his first novel, Keep Cool (1817). The novel portrays the phenomenon as a holdover from an aristocratic era that is immoral, pointless, antidemocratic, and anti-American.[79] His “Essay on Duelling” article for The Portico that same year attacked dueling as a gendered performance and refused to acknowledge it as “the unqualified evidence of manhood.”[240] Neal outlined the roles of both men and women in ending dueling,[241] arguing that “woman has most contributed towards the increase of this crime...and she is associated with all our hopes hereafter... She has made man a Duellist for her smile, and she can now change the spirit of opposition to forbearance.”[242] As for men, Neal believed that “In his closet every man wishes duelling abolished, and if every man who wishes it sincerely in private would but speak as firmly in publick [sic], it would be abolished.”[242]

Temperance

Neal adopted personal convictions against drinking to excess in his childhood that he maintained throughout his life, but he did not become associated with the temperance movement until after he returned to Portland, Maine from London. His first invitation to lecture an audience was for the annual address for the Portland Association for the Promotion of Temperance at the First Parish Church in February 1829.[111] Neal Dow, John Neal's cousin, was a core leader of the local movement toward prohibition policy, and in 1836 Neal engaged in public debates with his cousin, defending moderate wine drinking as an alternative to total abstinence.[243] It was in this period between the late 1830s and late 1840s that Neal became disillusioned with the temperance movement, which had moved away from a focus on moral suasion to enacting prohibition law, with Dow and his followers “instead of regarding the injunction, 'Be temperate in all things,' were furiously intemperate on the subject of temperance; making total abstinence the condition of citizenship, and almost of civilization.”[244] Neal remained convinced of “the evils of intemperance... They could not well be exaggerated; the only question was about the remedy.”[245]

Feminism

John Neal is remembered as America’s first women’s rights lecturer.[246] Starting in 1823 and continuing at least as late as 1869, he used magazine articles, short stories, novels, public speaking, political organizing, and personal relationships to advance feminist issues in the Unites States and England, reaching the height of his influence in this field circa 1843.[247] He declared intellectual equality between men and women, fought coverture, and demanded suffrage, equal pay, and better education for women. He also used his writing to explore the performative nature of gender.[248]

- Predecessors and successors

Aside from this early attack on coverture in 1823, Neal’s early feminist positions were primarily influenced by the written works of Mary Wollstonecraft, particularly her 1792 book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.[249] Catharine Macaulay and Judith Sargent Murray also influenced Neal. All three authors viewed poor standards in female education as the root of women’s problems.[250] Neal’s early feminist essays from the 1820s fill an intellectual gap between these earlier authors and their pre-Seneca Falls Convention successors like Sarah Moore Grimké, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Margaret Fuller.[251] This gap is credited to an association in English and American minds between women’s rights and scandals surrounding Macaulay’s and Wollstonecraft’s personal lives that pushed feminist writings into private correspondence from the 1790s through the early decades of the nineteenth century.[252] As a male writer insulated from many common forms of attack against female feminist thinkers, Neal’s advocacy was crucial in bringing the field back into the mainstream in England and the US.[253]

- Early essays

"I am for treating women like rational beings—not like spoilt children, who are never to be contradicted or thwarted... I would have them reasoned with,...not laughed at; put aside, reverently, with an appeal to their good sense, not by a sarcasm, a bow, or a joke; dealt plainly with, not flattered; spoken to, peremptorily, when they deserve it, but kindly and respectfully nevertheless. In one word, I would have women treated like men, of common sense.”

— John Neal, “Men and Women,” 1824[254]

John Neal’s first published feminist essay, “Men and Women,” appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine in October 1824 while Neal was living in London. It recalls the ideas of Macaulay, Murray, and Wollstonecraft about female education, but adds an exploration into the intellectual equality between men and women.[255] On education, he said, “Wait until women are educated like men—treated like men—and permitted to talk freely, without being put to shame, because they are women.” At that future time, he posited that the greatest of male writers “will be equalled by women.”[256] On the subject of intellectual equality, he “maintain[s] that women are not inferior to men, but only unlike men, in their intellectual properties” and “would have women treated like men, of common sense.”[257] Neal wove an insistence of intellectual equality into an even earlier “Essay on Duelling” article for The Portico in 1817 when he urged women to use “the reason that Heaven has apportioned so equally between her, and her brother” to eliminate the institution of dueling.[242]

Two months after “Men and Women” in 1824, Neal used Blackwood’s to make his first call for women’s suffrage.[74] Through published essays, debates, and personal communication while in England, Neal claims he convinced both John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham to take up women’s rights issues as well.[258]

Neal continued his writing on feminist issues after returning to Portland, Maine from London and also used his career as a touring lecturer to spread his ideas. Leveraging his magazine The Yankee in 1828 and 1829, he published the essays “Parties and Women,” “Capacities of Women,” and “Rights of Women,” the last of those being his most scathing, as it was prompted by the recent closure of the Boston High School for Girls.[259] Over the 1820s Neal shifted his focus from educational intellectual ideas to political and economic issues like coverture and suffrage.[260]

- Lectures

John Neal’s first experience with public speaking experience was before a Baltimore debating society as a young lawyer in 1823. Though the topic of the debate was slavery, and though most of the society’s members were enslavers of Black Americans, Neal saw the mood of the audience moving against the institution. Being “resolutely and heartily opposed to slavery” himself, Neal found the enslavers’ arguments against their own institution to be “weak and frivolous.”[261] In reply, he decided “to take the wrong side of [the] question” to “urge the best arguments [he] could, for others to answer,”[261] voicing an argument ostensibly in support of slavery that interwove the issue with the legal rights of women:

How long [women] shall be rendered by law incapable of acquiring, holding, or transmitting property, except under special conditions, like the slave? Take the best and most comprehensive definition of slavery...and you will be satisfied that one-half of your whole population...are born to slavery, that they live in slavery, and are dying in slavery.[262]

His limited presence on an 1823 Baltimore debate stage aside, Neal’s first true lecture to include feminist issues was an Independence Day address in Portland, Maine in 1832.[263] Filling in for a scheduled speaker who never showed, Neal gave an impromptu speech on freedom, declaring that without suffrage, women were victims of the same crime of taxation without representation that was the cause of the Revolutionary War.[73] He connected the topic to an attacks on slavery and coverture as well, prompting a dismissal in the Portland Advertiser that was typical of the age: “The subject was discussed in a very amusing and original manner, but we suspect the fair are well satisfied with their present influence, notwithstanding Mr. Neal’s objection that men make all the laws for the other sex, and give them no voice in legislation.”[264] For the following twenty-six years, Neal supplemented his income and broadened the reach of his ideas by making tours as a lecturer on many subjects, including women’s rights.[265]

At his most well-attended lecture titled “Rights of Women,” he spoke before a crowd of around 3,000 people in January 1843 at New York City’s largest auditorium at the time, the Broadway Tabernacle.[266] Sponsored by the Mechanics’ Library Association, Neal's speech targeted the timely topic of coverture: the speech occurred six years after the first law to grant married women the right to own property in New York was proposed (1836) and five years before New York’s model Married Women’s Property Act was passed (1848) and subsequently replicated nationwide.[267] He called for women’s suffrage, attacking the concept of “virtual representation” in government that opponents argued women enjoyed through men without needing to vote themselves: “Just reverse the condition of the two sexes: give to Women all the power now enjoyed by Men... What a clamour there would be then, about equal rights, about a privileged class, about being taxed without their own consent, and virtual representation, and all that!”[268] Neal also raised the intellectual equality argument and call for female education that he had been making for twenty years:

Steadfast as Death—steady as the everlasting Ocean, in their encroachments, Men have obtained the mastery over Women, not by superior virtue, nor by superior understanding, but by the original accident of superior strength; and after monopolizing all power, have extinguished her ambition, dwarfed her faculties, and brought her up to believe—the simpleton—that she was created only for the pleasure of man.[269]

- Brother Jonathan

The “Rights of Women” speech was widely covered, albeit dismissed, by the press, and Neal printed it later that year in the pages of Brother Jonathan magazine, of which he was editor.[270] He used that magazine in 1843 to publish his own essays calling for equal pay and better workplace conditions for women, and to host a printed debate of correspondence on the merits of women’s suffrage between himself and Eliza W. Farnham.[271] His short story “Idiosyncrasies,” also printed in Brother Jonathan in 1843, explored the male feminist perspective through the narration of a character named Lee:

And so, I began to look about me, and tried for a long while to understand why it was, that women were so changeable, and weak, and frivolous; and having found it in the Institutions of Society, as we men call them, we, the founders, framers, and supporters of those very institutions, which imprison the soul of woman, and set a seal upon her faculties—and seven seals upon the fountain of her thoughts; forbidding her to reason for herself, to enquire for herself, to judge for herself—nay even to believe for herself; and allowing her no share whatever in the glorious birthright we claim, of governing ourselves: Having found the cause, I say, in these institutions, the hand-work of Man, and believing in my heart...that where the evil was, there the remedy must be sought for, I went to work, with a determination to help the first woman I should meet with, having the courage and steadfastness of purpose, needed for such a struggle, up—up—and into the place she had been created for—that of entire companionship with MAN.[272]

- National Woman Suffrage Association

Neal became even more prominently involved with the women’s suffrage movement in his old age following the Civil War, both in Maine and nationally by supporting Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s and Susan B. Anthony’s National Woman Suffrage Association and writing for its journal, The Revolution. Stanton and Anthony recognized his work after his death in their History of Woman Suffrage.[273]

Slavery and racism

- Racist hypocrisy