Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Cyclonenim (talk | contribs) 4 years ago. (Update timer) |

| Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis | |

|---|---|

| |

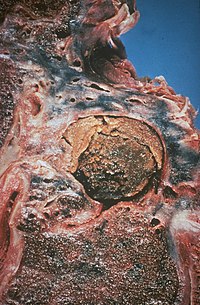

| An example of aspergilloma, one form of CPA, following tuberculosis. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Weight loss, cough, shortness of breath, haemoptysis, fatigue, malaise, chest pain, sputum production, fever[1] |

| Risk factors | Underlying respiratory disease,[2] genetic defects[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Via imaging (chest X-ray, high resolution CT scanning)[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Lung cancer, tuberculosis, other fungal infections[5] |

| Treatment | Antifungal medications (oral or intravenous),[6][7] surgery,[6] glucocorticoids[8] |

| Prognosis | Approximately 20-40% mortality at 3 years; 50-80% at 7-10 years[9][10][11] |

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (commonly abbreviated as CPA) is a long-term fungal infection caused by members of the Aspergillus genus—most commonly Aspergillus fumigatus.[8] The term describes several disease presentations with considerable overlap, ranging from an aspergilloma[12]—a clump of Aspergillus mold in the lungs—through to a subacute, invasive form known as chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis which affects people whose immune system is weakened. Many people affected by CPA have an underlying lung disease, most commonly tuberculosis (TB), allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, asthma or lung cancer.[8]

Classification

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a term encompasses a number of different presentations of varying severity. There is considerable overlap between disease forms which adds to confusion during diagnosis. The primary differentiation comes from radiological findings and serology.[8]

Aspergilloma

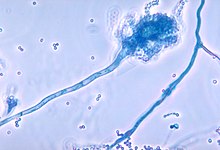

An aspergilloma is a fungus ball composed of Aspergillus hypha - the long filamentous strands which extend from the fungus to enable growth and reproduction.[13] They can arise within any bodily cavity, though in the context of CPA they form within pulmonary cavities that have been colonized by Aspergillus spp. If there is a single, stable cavity that provides minimal symptoms, the term 'simple aspergilloma' is commonly used to distinguish it from more severe forms of CPA.[14]

Aspergillus nodule

Aspergillus can form single or multiple nodules which may or may not form a cavity.[8] Whilst usually benign in nature, they can sometimes cause symptoms such as cough or an exacerbation of existing disease such as asthma.[15] Histologically, there is necrosis surrounded by granulomatous inflammation with some multinucleated giant cells present.[16]

Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis

When people without immunocompromise undergo formation of one or more pulmonary cavities, this is called chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (or CCPA).[8] Historically it was also known as "complex aspergilloma" in contrast to a "simple aspergilloma"; this is now considered inaccurate as many cases do not have a visible aspergilloma on imaging.[17] In contrast to aspergilloma and Aspergillus nodules, the vast majority of people with CCPA have positive tests for IgG antibodies.[18][19]

Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis

When CCPA is left untreated, it can progress to a form of aspergillosis known as chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (or CFPA).[8] As a result of the ongoing inflammation over an extended period of time, extensive fibrosis of the lung parenchyma occurs. This leads to a state known colloquially as "destroyed lung", and has features resembling treated pulmonary TB.[14][20]

Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis

Also known as subacute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, this form of CPA leads to progressive features over the course of one to three months—usually in people with some degree of immunocompromise. It is more common in people who are elderly or dependent on alcohol, or with diseases such as diabetes, malnutrition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or HIV/AIDS.[8][21] In contrast to CCPA, for example, IgG antibodies for Aspergillus or an antigen called galactomannan may be found in the blood as well as in sputum samples.[21]

Signs and symptoms

People with CPA typically present with a prolonged, several month history of unintentional weight loss, chronic cough which is normally productive of sputum, shortness of breath and haemoptysis.[8] One small case series of 18 people found these to be the most common presenting symptoms. Less common symptoms include severe fatigue or malaise, chest pain, sputum production without cough, and fever. Fever would not typically be expected unless they had the subacute invasive subtype.[14] Furthermore, it is possible for less severe subtypes to be asymptomatic.[8] Beyond the direct symptoms, it is possible to have general signs of underlying lung pathology such as digital clubbing—especially when there has been an underlying disease such as TB or where disease has caused heart failure (known as cor pulmonale).[22]

Complications

CPA can cause bleeding into the lung parenchyma which can range from mild to life-threatening. If left untreated, as the disease progresses the fungus can spread into the bloodstream causing a state known as fungemia. This widespread infection can distribute fungal spores to other parts of the body, and lead to areas of infarction, and cause hemorrhages.[23]

Causes

Aspergillosis is an infection caused by fungi from the genus Aspergillus. The vast majority of cases are caused by Aspergillus fumigatus—a filamentous fungus found uniqutiously in every continent on the planet including Antarctica.[8][24] Other species of Aspergillus include A. flavus and A. terreus.[8]

The major risk factors for CPA are previous cavity formation from other respiratory conditions. Examples include collapsed lungs which have formed bullae, chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), lung cancer, and fibrocavitary sarcoidosis.[25][26] Another risk factor is immunosuppression; most commonly, this includes allogeneic stem cell transplantation, prolonged neutropaenia, immunosuppressive drug therapy, chronic granulomatous disease and haematological malignancies. Certain demographics are also at higher risk, including the elderly, male gender and those with a low body mass index.[27]

There appears to be increasing evidence for complex genetic factors increasing the risk of developing CPA, such as defects to toll-like receptor (TLR) 4,[28] IL1 and IL15,[29] TLR3, TLR10, TREM1, VEGFA, DENND1B, and PLAT.[30]

Mechanism

The full underlying pathogenesis is not completely understood. Most people with CPA have functional immune status, but usually have underlying structural damage to the lungs from an underlying process or disease. Most commonly, pre-existing pulmonary cavities from other diseases such as TB become colonised with Aspergillus conidia which have been inhaled—humans inhale between 1,000 and 10 billion spores per day, of which A. fumigatus is the most common.[31]

Aspergillomas themselves usually form in pre-existing cavities but the cavities may form directly from CPA.[8] People with pulmonary TB with a cavity larger than 2 cm appear to have a 20% increased risk of developing CPA.[32]

It is postulated that conidia, once inhaled, are attacked by the host immune defences—specifically phagocytes and alveolar macrophage resident in the small airways. It is unknown whether these defences are sufficient to clear conidia or whether they are directly responsible for the inflammation leading to CPA. Some Aspergillus have the ability to inhibit phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activation which is one of the core defence systems against filamentous fungi, which may increase susceptibility of the host to CPA.[33]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CPA is often initially considered when patients present with a history of unintentional weight loss and fatigue. Confirmation of this suspicison is normally achieved with a combination of radiological imaging and serological testing, with the goal of excluding common differentials like TB and finding evidence of fungus present. Whilst cavities seen on chest X-rays can raise suspicion, positive IgG testing for Aspergillus is required for confirmation.[8]

Sputum samples can be sent for culture, but where these return negative patients should undergo bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage for further culture samples.[21] Concurrent infections with non-TB mycobacteria, or atypical infections such as MRSA or Pseudomonas aeruginosa are common and these can also form cavities.[8]

To confirm the presence of an aspergilloma, there needs to be radiological evidence of a round mass in the lungs with confirmatory evidence either from culture or IgG testing.[34] The distinction between simple aspergilloma, and more advanced CCPA, will depend on the severity of inflammation, radiological evidence, and changes over time.[8] To confirm CCPA, the current criteria is one large cavity or ≥ 2 small cavities with or without aspergilloma. This must be accompanied by at least one symptom of fever, weight loss, fatigue, cough, sputum production, haemoptysis or shortness of breath for at least 3 months. Furthermore, as with aspergilloma, there must be positive IgG testing but this can be with or without culture.[21] To confirm Aspergillus nodules as opposed to aspergilloma, these must be seen directly on imaging or confirmed by percutaneous or surgical biopsy.[35]

The fibrosing form—CFPA—has similar criteria to CCPA but will be accompanied by significant fibrosis seen on either biopsy, tomosynthesis, or high resolution computed tomography.[8]

If CPA has progressed to subacute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, there must be a degree of immunosuppression. The microbiological criteria are similar to those of invasive aspergillosis but normally slower in progression, i.e. months rather than weeks.[21] Furthermore, there must be evidence of IgG or galactomannan in the blood and a confirmatory biopsy of affected tissue.[19][34]

Treatment

People with single aspergillomas generally do well with surgery to remove the aspergilloma, and are best given pre-and post-operative antifungal medications. Often, no treatment is necessary. However, if a person coughs up blood (haemoptysis), treatment may be required (usually angiography and embolization, surgery or taking tranexamic acid). Angiography (injection of dye into the blood vessels) may be used to find the site of bleeding which may be stopped by shooting tiny pellets into the bleeding vessel.[citation needed]

For chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis, lifelong use of antifungal medications is usual. Itraconazole and voriconazole are first and second-line antifungal agents, respectively. Posaconazole can be used as third-line agent, for people with CPA who are intolerant of or developed resistance to the first and second-line agents. Regular chest X-rays, serological and mycological parameters as well as quality of life questionnaires are used to monitor treatment progress. It is important to monitor the blood levels of antifungals to ensure optimal dosing as individuals vary in their absorption levels of these medications.[citation needed]

Prognosis

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (August 2019) |

Epidemiology

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (August 2019) |

References

- ^ Denning DW, Riniotis K, Dobrashian R, Sambatakou H (October 2003). "Chronic cavitary and fibrosing pulmonary and pleural aspergillosis: case series, proposed nomenclature change, and review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 37 Suppl 3: S265-80. doi:10.1086/376526. PMID 12975754.

- ^ Smith NL, Denning DW (April 2011). "Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma". The European Respiratory Journal. 37 (4): 865–72. doi:10.1183/09031936.00054810. PMID 20595150.

- ^ Carvalho A, Pasqualotto AC, Pitzurra L, Romani L, Denning DW, Rodrigues F (February 2008). "Polymorphisms in toll-like receptor genes and susceptibility to pulmonary aspergillosis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (4): 618–21. doi:10.1086/526500. PMID 18275280.

- ^ Desai SR, Hedayati V, Patel K, Hansell DM (October 2015). "Chronic Aspergillosis of the Lungs: Unravelling the Terminology and Radiology". European Radiology. 25 (10): 3100–7. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-3690-7. PMID 25791639.

- ^ Kim SH, Kim MY, Hong SI, Jung J, Lee HJ, Yun SC, et al. (July 2015). "Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis-mimicking Tuberculosis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 61 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1093/cid/civ216. PMID 25778752.

- ^ a b Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Ader F, Chakrabarti A, Blot S, et al. (January 2016). "Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management". The European Respiratory Journal. 47 (1): 45–68. doi:10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. PMID 26699723.

- ^ Patterson TF, Thompson GR, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, et al. (August 2016). "Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 63 (4): e1–e60. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw326. PMID 27365388.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Denning, David W. "Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis". www.uptodate.com. UpToDate. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Lowes D, Al-Shair K, Newton PJ, Morris J, Harris C, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Denning DW (February 2017). "Predictors of mortality in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis". The European Respiratory Journal. 49 (2). doi:10.1183/13993003.01062-2016. PMID 28179437.

- ^ Tomlinson JR, Sahn SA (September 1987). "Aspergilloma in sarcoid and tuberculosis". Chest. 92 (3): 505–8. doi:10.1378/chest.92.3.505. PMID 3622028.

- ^ Ohba H, Miwa S, Shirai M, Kanai M, Eifuku T, Suda T, et al. (May 2012). "Clinical characteristics and prognosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis". Respiratory Medicine. 106 (5): 724–9. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.014. PMID 22349065.

- ^ Judson MA, Stevens DA (October 2001). "The treatment of pulmonary aspergilloma". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 2 (10): 1375–7. PMID 11890350.

- ^ Brand A (2012). "Hyphal growth in human fungal pathogens and its role in virulence". International Journal of Microbiology. 2012: 517529. doi:10.1155/2012/517529. PMC 3216317. PMID 22121367.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Denning DW, Riniotis K, Dobrashian R, Sambatakou H (October 2003). "Chronic cavitary and fibrosing pulmonary and pleural aspergillosis: case series, proposed nomenclature change, and review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 37 Suppl 3: S265-80. doi:10.1086/376526. PMID 12975754.

- ^ Muldoon EG, Sharman A, Page I, Bishop P, Denning DW (August 2016). "Aspergillus nodules; another presentation of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis". BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 16 (1): 123. doi:10.1186/s12890-016-0276-3. PMC 4991006. PMID 27538521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Farid S, Mohamed S, Devbhandari M, Kneale M, Richardson M, Soon SY, et al. (August 2013). "Results of surgery for chronic pulmonary Aspergillosis, optimal antifungal therapy and proposed high risk factors for recurrence--a National Centre's experience". Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 8: 180. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-8-180. PMC 3750592. PMID 23915502.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Godet C, Philippe B, Laurent F, Cadranel J (2014). "Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: an update on diagnosis and treatment". Respiration; International Review of Thoracic Diseases. 88 (2): 162–74. doi:10.1159/000362674. PMID 24943102.

- ^ Coleman RM, Kaufman L (February 1972). "Use of the immunodiffusion test in the serodiagnosis of aspergillosis". Applied Microbiology. 23 (2): 301–8. PMC 380335. PMID 4622826.

- ^ a b Hagiwara E, Sekine A, Sato T, Baba T, Shinohara T, Endo T, et al. (November 2008). "[Clinical features of chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis treated with voriconazole in patients with chronic respiratory disease]". Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi = the Journal of the Japanese Respiratory Society. 46 (11): 864–9. PMID 19068757.

- ^ Kosmidis C, Newton P, Muldoon EG, Denning DW (April 2017). "Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis: a cause of 'destroyed lung' syndrome". Infectious Diseases. 49 (4): 296–301. doi:10.1080/23744235.2016.1232861. PMID 27658458.

- ^ a b c d e Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Ader F, Chakrabarti A, Blot S, et al. (January 2016). "Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management". The European Respiratory Journal. 47 (1): 45–68. doi:10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. PMID 26699723.

- ^ Bongomin F, Kwizera R, Atukunda A, Kirenga BJ (September 2019). "Cor pulmonale complicating chronic pulmonary aspergillosis with fatal consequences: Experience from Uganda". Medical Mycology Case Reports. 25: 22–24. doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.07.001. PMC 6614533. PMID 31333999.

- ^ Dimopoulos G, Karampela I (March 2009). "Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Different Diseases for the Same Pathogen". Clinical Pulmonary Medicine. 16 (2): 68–73. doi:10.1097/CPM.0b013e31819b14b8. ISSN 1068-0640.

- ^ Godinho, Valéria M.; Gonçalves, Vívian N.; Santiago, Iara F.; Figueredo, Hebert M.; Vitoreli, Gislaine A.; Schaefer, Carlos E. G. R.; Barbosa, Emerson C.; Oliveira, Jaquelline G.; Alves, Tânia M. A. (May 2015). "Diversity and bioprospection of fungal community present in oligotrophic soil of continental Antarctica". Extremophiles: Life Under Extreme Conditions. 19 (3): 585–596. doi:10.1007/s00792-015-0741-6. ISSN 1433-4909. PMID 25809294.

- ^ Smith, N. L.; Denning, D. W. (April 2011). "Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma". The European Respiratory Journal. 37 (4): 865–872. doi:10.1183/09031936.00054810. ISSN 1399-3003. PMID 20595150.

- ^ Pena, Tahuanty A.; Soubani, Ayman O.; Samavati, Lobelia (February 2011). "Aspergillus lung disease in patients with sarcoidosis: a case series and review of the literature". Lung. 189 (2): 167–172. doi:10.1007/s00408-011-9280-9. ISSN 1432-1750. PMID 21327836.

- ^ Jhun, Byung Woo; Jung, Woo Jin; Hwang, Na Young; Park, Hye Yun; Jeon, Kyeongman; Kang, Eun-Suk; Koh, Won-Jung (2017). "Risk factors for the development of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease". PloS One. 12 (11): e0188716. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188716. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5708732. PMID 29190796.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Carvalho A, Pasqualotto AC, Pitzurra L, Romani L, Denning DW, Rodrigues F (February 2008). "Polymorphisms in toll-like receptor genes and susceptibility to pulmonary aspergillosis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (4): 618–21. doi:10.1086/526500. PMID 18275280.

- ^ Smith NL, Hankinson J, Simpson A, Bowyer P, Denning DW (August 2014). "A prominent role for the IL1 pathway and IL15 in susceptibility to chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (8): O480-8. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12473. PMID 24274595.

- ^ Smith NL, Hankinson J, Simpson A, Denning DW, Bowyer P (November 2014). "Reduced expression of TLR3, TLR10 and TREM1 by human macrophages in Chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis, and novel associations of VEGFA, DENND1B and PLAT". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (11): O960-8. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12643. PMID 24712925.

- ^ Brown, Gordon D.; Denning, David W.; Gow, Neil A. R.; Levitz, Stuart M.; Netea, Mihai G.; White, Theodore C. (2012-12-19). "Hidden killers: human fungal infections". Science Translational Medicine. 4 (165): 165rv13. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. ISSN 1946-6242. PMID 23253612.

- ^ Sonnenberg P, Murray J, Glynn JR, Thomas RG, Godfrey-Faussett P, Shearer S (February 2000). "Risk factors for pulmonary disease due to culture-positive M. tuberculosis or nontuberculous mycobacteria in South African gold miners". The European Respiratory Journal. 15 (2): 291–6. PMID 10706494.

- ^ Cornish EJ, Hurtgen BJ, McInnerney K, Burritt NL, Taylor RM, Jarvis JN, et al. (May 2008). "Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-independent resistance to Aspergillus fumigatus in alveolar macrophages". Journal of Immunology. 180 (10): 6854–67. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6854. PMID 18453606.

- ^ a b Hope, W. W.; Walsh, T. J.; Denning, D. W. (May 2005). "The invasive and saprophytic syndromes due to Aspergillus spp". Medical Mycology. 43 Suppl 1: S207–238. doi:10.1080/13693780400025179. ISSN 1369-3786. PMID 16110814.

- ^ Muldoon, Eavan G.; Sharman, Anna; Page, Iain; Bishop, Paul; Denning, David W. (August 2016). "Aspergillus nodules; another presentation of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis". BMC pulmonary medicine. 16 (1): 123. doi:10.1186/s12890-016-0276-3. ISSN 1471-2466. PMC 4991006. PMID 27538521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)