Danelaw: Difference between revisions

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

Most of England's rebellions in the post-Norman climate, are sourced to this region. Most maps outlining the areas which supported King John, show a glaring lack of faith in him, in what was lately called the Danelaw, except a few pockets north or east of Watling Street. The [[Peasants' Revolt]] and [[Eastern Association]] convictions were strongest in this large part of England later on in history. Religious individualism, whether Catholic or Puritan, struck a chord in the old Danelaw area, all for the rights of freemen over the serfdom which remained in the West Country, loyal to the Crown. For religious struggles, see [[Pilgrimage of Grace]] and [[Pilgrim (Plymouth Colony)]]. |

Most of England's rebellions in the post-Norman climate, are sourced to this region. Most maps outlining the areas which supported King John, show a glaring lack of faith in him, in what was lately called the Danelaw, except a few pockets north or east of Watling Street. The [[Peasants' Revolt]] and [[Eastern Association]] convictions were strongest in this large part of England later on in history. Religious individualism, whether Catholic or Puritan, struck a chord in the old Danelaw area, all for the rights of freemen over the serfdom which remained in the West Country, loyal to the Crown. For religious struggles, see [[Pilgrimage of Grace]] and [[Pilgrim (Plymouth Colony)]]. |

||

The region, even after this part of England was tied to the [[Duke of Brittany]] in right of his Richmond honour granted by the Duke of Normandy, who was King of all England, retained North Sea economy, especially with Flanders, in the woolens trade. This was, for a time, buttressed by the Anglo-Burgundian alliance that was essential for holding the [[Pale of Calais]], lost by [[Mary I of England]] and [[Philip II of Spain]] in their disasterous war with France. Philip was titular Duke of Burgundy and his political opponent was [[William the Silent]], whose son's actually welcomed rule (against Spain's overlordship) over the people was championed by [[Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester]], made Governor-General of the [[Dutch Republic]] under the terms of the [[Treaty of Nonsuch]]. These investments made by [[Elizabeth I of England]] would eventually influence the Royalty of England itself, under [[William III of England]] and continued by his Protestant Danish and German successors, whose own ties to mediaeval England, apart from Saxon heritage, |

The region, even after this part of England was tied to the [[Duke of Brittany]] in right of his Richmond honour granted by the Duke of Normandy, who was King of all England, retained North Sea economy, especially with Flanders, in the woolens trade. This was, for a time, buttressed by the Anglo-Burgundian alliance that was essential for holding the [[Pale of Calais]], lost by [[Mary I of England]] and [[Philip II of Spain]] in their disasterous war with France. Philip was titular Duke of Burgundy and his political opponent was [[William the Silent]], whose son's actually welcomed rule (against Spain's overlordship) over the people was championed by [[Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester]], made Governor-General of the [[Dutch Republic]] under the terms of the [[Treaty of Nonsuch]]. These investments made by [[Elizabeth I of England]] would eventually influence the Royalty of England itself, under [[William III of England]] and continued by his Protestant Danish and German successors, whose own ties to mediaeval England, apart from Saxon heritage, were the [[Steelyard]] in London and the [[Hanseatic League]]'s [[Kontor]] depots mostly on the [[German Ocean]] coast of England. |

||

==Genetic heritage== |

==Genetic heritage== |

||

Revision as of 05:40, 5 February 2010

| History of England |

|---|

|

|

|

The Danelaw, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (also known as the Danelagh; Old English: Dena lagu; Danish: Danelagen), is a historical name given to the part of England in which the laws of the "Danes" held sway[1] and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. It is contrasted with "West Saxon Law" and "Mercian law". The term has been extended by modern historians to be geographical. The areas that comprised the Danelaw are in northern and eastern England. The origins of the Danelaw arose from the Viking expansion of the 9th century, although the term was not used to describe a geographic area until the 11th century. With the increase in population and productivity in Scandinavia, Viking warriors sought treasure and glory in nearby Britain.

Danelaw is also used to describe the set of legal terms and definitions created in the treaties between the English king, Alfred the Great, and the Danish warlord, Guthrum the Old, written following Guthrum's defeat at the Battle of Ethandun in 878. In 886, the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum was formalised, defining the boundaries of their kingdoms, with provisions for peaceful relations between the English and the Vikings.

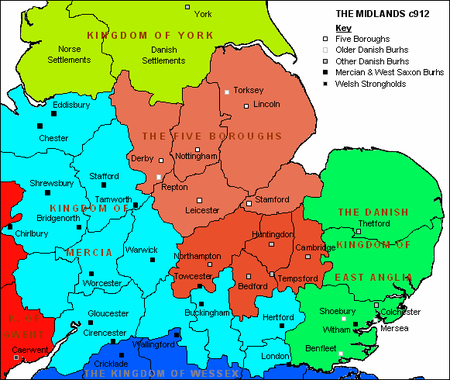

The Danish laws held sway in the Kingdom of Northumbria and Kingdom of East Anglia, and the lands of the Five Boroughs of Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Stamford and Lincoln.

The prosperity of the Danelaw, especially Eoferic (Danish Jórvík, modern York), led to its becoming a target for later Viking raiders. Conflict with Wessex and Mercia sapped the strength of the Danelaw. The waning of its military power together with the Viking onslaughts led to its submission to Edward the Elder in return for protection. It was to be part of his Kingdom of England, and no longer a province of Denmark, as the English laid final claim to it.

History

From about AD 800 waves of Danish assaults on the coastlines of the British Isles were gradually followed by a succession of Danish settlers. Danish raiders first began to settle in England starting in 865, when brothers Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless wintered in East Anglia. They soon moved north and in 867 captured Northumbria and its capital, York, defeating both the recently deposed King Osberht of Northumbria, as well as the usurper Ælla of Northumbria. The Danes then placed an Englishman, Ecgberht I of Northumbria, on the throne of Northumbria as a puppet.[2]

King Æthelred of Wessex and his brother, Alfred, led their army against the Danes at Nottingham, but the Danes refused to leave their fortifications. King Burgred of Mercia then negotiated peace with Ivar, with the Danes' keeping Nottingham in exchange for leaving the rest of Mercia unmolested.

Under Ivar the Boneless, the Danes continued their invasion in 869 by defeating King Edmund of East Anglia at Hoxne and conquering East Anglia.[3] Once again, the brothers Æthelred and Alfred attempted to stop Ivar by attacking the Danes at Reading. They were repelled with heavy losses. The Danes pursued, and on 7 January 871, Æthelred and Alfred defeated the Danes at the Battle of Ashdown. The Danes retreated to Basing (in Hampshire), where Æthelred attacked and was, in turn, defeated. Ivar was able to follow up this victory with another in March at Meretum (now Marton, Wiltshire).

On 23 April 871, King Æthelred died and Alfred succeeded him as King of Wessex. His army was weak and he was forced to pay tribute to Ivar in order to make peace with the Danes. During this peace the Danes turned to the north and attacked Mercia, a campaign that lasted until 874. Both the Danish leader Ivar and Mercian leader Burgred died during this campaign. Ivar was succeeded by Guthrum the Old, who finished the campaign against Mercia. In ten years the Danes gained control over East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia, leaving only Wessex to resist.[4]

Guthrum and the Danes brokered peace with Wessex in 876, when they captured the fortresses of Wareham and Exeter. Alfred laid siege to the Danes, who were forced to surrender after reinforcements were lost in a storm. Two years later, Guthrum again attacked Alfred, surprising him by attacking his forces wintering in Chippenham. King Alfred was saved when the Danish army coming from his rear was destroyed by inferior forces at Countisbury Hill. Alfred was forced into hiding for a time, before returning in the spring of 878 to gather an army and attack Guthrum at Ethandun. The Danes were defeated and retreated to Chippenham, where King Alfred laid siege and soon forced them to surrender. As a term of surrender, King Alfred demanded that Guthrum be baptised a Christian; King Alfred served as his godfather.[5]

This peace lasted until 884, when Guthrum again attacked Wessex. Alfred defeated him, with peace codified in the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum.[6] The treaty outlined the boundaries of the Danelaw and allowed for Danish self-rule in the region. The Danelaw represented a consolidation of power for Alfred; the subsequent conversion of Guthrum to Christianity underlines the ideological significance of this shift in the balance of power.

The reasons for the waves of immigration were complex and bound to the political situation in Scandinavia at that time; moreover, they occurred when Viking settlers were also establishing their presence in the Hebrides, Orkney, the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, France (Normandy), Russia and Ukraine (see Kievan Rus').[7] Polabian Slavs (Wends) settled in parts of England, apparently as Danish allies.[citation needed]

The Danes never gave up their designs for England. From 1016 to 1035 the English kingdom was ruled by Canute the Great as part of a North Sea Danish Empire. In 1066, two rival Viking factions led invasions of England. Harald Hardrada took York but was defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. William of Normandy and his Normans defeated Anglo-Saxon armies at the Battle of Hastings in Sussex and accepted the submission of the child Edgar, last in the line of Wessex kings at Berkhamsted.

The Danelaw appeared in legislation as late as the early twelfth century with the Leges Henrici Prime, being referred to as one of the laws together with those of Wessex and Mercia into which England was divided.

Danish-Norwegian conflict in the North Sea

In the years between the Sack of Lindesfarne in 793 and the Danish invasion of East Anglia in 865, Norwegian settlers founded the site of modern Dublin and fought as mercenaries in Irish tribal wars, liberally intermarrying with their Irish allies. Some 10 years later a Danish fleet probably from Great Heathen Army in Anglia arrived and attacked the settlement with the Irish and Norwegian enemies of the Hiberno-Norse, but were repulsed. It is also said in Irish and northern English oral history that Ivar the Boneless, and in some accounts also Ubbe Ragnarsson, died not in the Mercian campaign, but drowned fighting the Hiberno-Norse in the Irish sea. Dublin and other major Irish towns were under Danish rule for the next 100–200 years.

The haste with which the Danes resumed their attack on Norse Dublin before consolidating their control of Saxon England indicates that the entire Danish invasion was not primarily aimed at the conquest of Saxon England, but to secure a North Sea base of operations to use as a springboard in the conflict with the Norwegians, who controlled an extensive trade network in the Orkneys, the Hebrides, the Isle of Man, the Isle of Wight, and Ireland, which exported goods as the Danes did, from the British Isles south-east through Kievan Rus as far as Constantinople and Baghdad, following the Dniepr from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

In the 11th century, when King Magnus I had freed Norway from Cnut the Great, the terms of the peace treaty provided that the first of the two kings Magnus (Norway) and Harthacnut (Denmark) to die would leave their dominion as an inheritance to the other. When Edward the Confessor ascended the throne of a united Dano-Saxon England, a Norse army was raised from every Norwegian colony in the British Isles and attacked Edward's England in support of Magnus', and after his death, his brother Harald Hardråde's, claim to the English throne. On the accession of Harold Godwinson after the death of Edward the Confessor, Hardraada invaded Northumbria with the support of Harold's brother Tostig Godwinson, and was defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge the week before William I's victory at the Battle of Hastings.

Timeline

800 Waves of Danish assaults on the coastlines of the British Isles were gradually followed by a succession of settlers.

Ragnar Lodbrok's execution

865 Danish raiders first began to settle in England. Led by brothers Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, they wintered in East Anglia, where they demanded and received tribute in exchange for a temporary peace. From there they moved north and attacked Northumbria, which was in the midst of a civil war between the deposed king Osberht and a usurper Ælla. The Danes used the civil turmoil as an opportunity to capture York, which they sacked and burned.

867 Following the loss of York, Osberht and Ælla formed an alliance against the Danes. They launched a counterattack, but the Danes killed both Osberht and Ælla and set up a puppet king on Northumbrian throne. In response, King Æthelred of Wessex, along with his brother Alfred marched against the Danes, who were positioned behind fortifications in Nottingham, but were unable to draw them into battle. In order to establish peace, King Burhred of Mercia ceded Nottingham to the Danes in exchange for leaving the rest of Mercia undisturbed.

869 Ivar the Boneless returned and demanded tribute from King Edmund of East Anglia.

870 King Edmund refused, Ivar the Boneless defeated and captured him at Hoxne and brutally sacrificed his heart to Odin in a so-called “blood eagle ritual”, in the process adding East Anglia to the area controlled by the invading Danes. King Æthelred and Alfred attacked the Danes at Reading, but were repulsed with heavy losses. The Danes pursued them.

871 On January 7, they made their stand at Ashdown (on what is the Berkshire/North Wessex Downs now in Oxfordshire). Æthelred could not be found at the start of battle, as he was busy praying in his tent, so Alfred led the army into battle. Æthelred and Alfred defeated the Danes, who counted among their losses five jarls (nobles). The Danes retreated and set up fortifications at Basing in Hampshire, a mere 14 miles (23 km) from Reading. Æthelred attacked the Danish fortifications and was routed. Danes followed up victory with another victory in March at Meretum (now Marton, Wiltshire).

King Æthelred died on April 23, 871 and Alfred took the throne of Wessex, but not before seriously considering abdicating the throne in light of the desperate circumstances, which were further worsened by the arrival in Reading of a second Danish army from Europe. For the rest of the year Alfred concentrated on attacking with small bands against isolated groups of Danes. He was moderately successful in this endeavor and was able to score minor victories against the Danes, but his army was on the verge of collapse. Alfred responded by paying off the Danes in order for a promise of peace. During the peace the Danes turned north and attacked Mercia, which they finished off in short order, and captured London in the process. King Burgred of Mercia fought in vain against the Ivar the Boneless and his Danish invaders for three years until 874, when he fled to Europe. During Ivar’s campaign against Mercia he died and was succeeded by Guthrum the Old as the main protagonist in the Danes’ drive to conquer England. Guthrum quickly defeated Burgred and placed a puppet on the throne of Mercia. The Danes now controlled East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia, with only Wessex continuing to resist.

875 The Danes settled in Dorsetshire, well inside of Alfred’s Kingdom of Wessex, but Alfred quickly made peace with them.

876 The Danes broke the peace when they captured the fortress of Wareham, followed by a similar capture of Exeter in 877.

877 Alfred laid siege, while the Danes waited for reinforcements from Scandinavia. Unfortunately for the Danes, the fleet of reinforcements encountered a storm and lost more than 100 ships, and the Danes were forced to return to East Mercia in the north.

878 In January Guthrum led an attack against Wessex that sought to capture Alfred while he wintered in Chippenham. Another Danish army landed in south Wales and moved south with the intent of intercepting Alfred should he flee from Guthrum’s forces. However, they stopped during their march to capture a small fortress at Countisbury Hill, held by a Wessex ealdorman named Odda. The Saxons, led by Odda, attacked the Danes while they slept and defeated the superior Danish forces, saving Alfred from being trapped between the two armies. Alfred was forced to go into hiding for the rest of the winter and spring of 878 in the Somerset marshes in order to avoid the superior Danish forces. In the spring Alfred was able to gather an army and attacked Guthrum and the Danes at Ethandun. The Danes were defeated and retreated to Chippenham, where the English pursued and laid siege to Guthrum’s forces. The Danes were unable to hold out without relief and soon surrendered. Alfred demanded as a term of the surrender that Guthrum become baptized as a Christian, which Guthrum agreed to do, with Alfred acting as his Godfather. Guthrum was true to his word and settled in East Anglia, at least for a while.

884 Guthrum attacked Kent, but was defeated by the English. This led to the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, which established the boundaries of the Danelaw and allowed for Danish self-rule in the region. Those who would not abide by the terms of peace returned to Ragnar Lodbrok's old haunts in the Marches of Neustria, what was to become Normandy under their settlement in the County of Rouen.

902 Essex submits to Æthelwald.

903 Æthelwald incites the East Anglian Danes into breaking the peace. They ravage Mercia before winning a pyrrhic victory that saw the death of Æthelwald and the Danish King Eohric; this allows Edward the Elder to consolidate power.

911 The English defeat the Danes at the Battle of Tettenhall. The Northumbrians ravage Mercia but are trapped by Edward and forced to fight.

917 In return for peace and protection The Kingdoms of Essex and East Anglia accept Edward the Elder as their suzerain overlord.

Æthelflæd (also known as Ethelfleda) Lady of the Mercians, takes the borough of Derby.

918 The borough of Leicester submits peaceably to Æthelflæd's rule. The people of York promise to accept her as their overlord, but she dies before this could come to fruition. She is succeeded by her brother, the Kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex united in the person of King Edward.

919 Norwegian Vikings under King Rægnold (Ragnald son of Sygtrygg) of Dublin take York.

920 Edward is accepted as father and lord by the King of the Scots, by Rægnold, the sons of Eadulf, the English, Norse, Danes and others all of whom dwell in Northumbria, and the King and people of the Strathclyde Welsh.

954 Eric Bloodaxe driven out of Northumbria, dies marking the end of the prospect of a Northern Viking Kingdom stretching from York to Dublin and the Isles. The Irish-Norse, as they are called, either flee to Dublin or take part in the settlement of the Cotentin, whose placenames retain the Irish Norse etymology, when distinct from Gallo-Roman or Frankish.

St. Brice's Day Massacre

1016 After the death of his father who had renewed conflict with England, Sweyn Forkbeard, Cnut the Great grants the Jarldom of East Anglia to the Dane Thorkell the Tall and the Jarldom of Northumbria to the Norwegian Eiríkr Hákonarson. Cnut also retains Eadric Streona as his Earl of Mercia, but plants himself and the Danish royal family at Winchester in Wessex, before also apportioning this to Godwin, Earl of Wessex.

1066 Battle of Stamford Bridge is fought by Harald III of Norway with the aid of Tostig Godwinson and both die at the army of Harold II of England.

1069 William I of England conducts the Harrying of the North under his lieutenants. Hereward the Wake lasts for a very long time in the Fens.

1071 Alan Rufus is granted the Honour of Richmond, which is based in Yorkshire (which at that time included Lancashire and Westmorland), Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, Suffolk, Hertfordshire, Essex, Hampshire and Dorset. Most of the Breton honour is thus clearly based in the Danelaw, whilst the Norman holdings are based in Wessex as the royal demesne. Rufus is known as the 'magnate of East Anglia', in addition to Richmondshire being known as the 'land of Count Alan'. The chief port of Richmond is Boston, Lincolnshire. Rufus is interred within Bury St Edmunds Abbey, Suffolk where he had made grants to the religious order there.

1135 This area of England remains aristocratic and the source of baronial opposition to the Empress Matilda (whose strength lay in the West Country), siding with Stephen of England in the Anarchy, which lasts until 1154. Gilbert de Gant, Earl of Lincoln and Alan, 1st Earl of Richmond are present at the Battle of Lincoln (1141). The latter also assaults William Fitzherbert, Archbishop of York, at Ripon Minster.

1162 The last Danegeld is collected by the new Angevin dynasty, under Henry II of England, grandson of Henry I of England whose legislation (Leges Henrici Prime) is the last surviving record of the Danelaw as a recognisable institution of England.

Geography

The area occupied by the Danelaw was roughly the area to the north of a line drawn between London and Chester, excluding the portion of Northumbria to the east of the Pennines.

Five fortified towns became particularly important in the Danelaw: Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Stamford and Lincoln, broadly delineating the area now called the East Midlands. These strongholds became known as the Five Boroughs. Borough derives from the Old English word burg (which in turn derives from the German word Burg, meaning castle), meaning a fortified and walled enclosure containing several households—anything from a large stockade to a fortified town. The meaning has since developed further.

Four of the five boroughs became county towns — of the counties of Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. However, Stamford failed to gain such status—perhaps because of the nearby autonomous territory of Rutland.

The influence of this period of Scandinavian settlement can still be seen in the North of England and the East Midlands, most evidently in placenames: name endings such as "howe", "by" or "thorp" having Norse origins.

Legal concepts of the Danelaw

The Danelaw was an important factor in the establishment of a civilian peace in the neighbouring Anglo-Saxon and Viking communities. It established, for example, equivalences in areas of legal contentiousness, such as the amount of reparation that should be payable in weregild.

Many of the legalistic concepts were compatible; for example the Viking wapentake, the standard for land division in the Danelaw, was effectively interchangeable with the hundred. The use of the execution site and cemetery at Walkington Wold in East Yorkshire suggests a continuity of judicial practice.[9]

Enduring impact of the Danelaw

Old Norse and Old English were still mutually comprehensible to a small degree. The mixed language of the Danelaw caused the incorporation of many Norse words into the English language, including the word law itself, sky and window, and the third person plural pronouns they, them and their. Many Old Norse words still survive in the dialects of Northeastern England. Around 600 English words we speak today come from old Norse for example ‘ill’ ‘egg’ ‘die ‘knife’ and ‘take.’

English styles of art and craft were also affected by the Vikings, the Vikings style of stone carving was adopted by the English, and as the Vikings became Christian, the combined style of decoration can be found on many stone crosses and hog back (stone carved grave markers.) gravestones in The Danelaw. There are the remains of more than 500 such gravestones and crosses in Yorkshire alone.

Most of England's rebellions in the post-Norman climate, are sourced to this region. Most maps outlining the areas which supported King John, show a glaring lack of faith in him, in what was lately called the Danelaw, except a few pockets north or east of Watling Street. The Peasants' Revolt and Eastern Association convictions were strongest in this large part of England later on in history. Religious individualism, whether Catholic or Puritan, struck a chord in the old Danelaw area, all for the rights of freemen over the serfdom which remained in the West Country, loyal to the Crown. For religious struggles, see Pilgrimage of Grace and Pilgrim (Plymouth Colony).

The region, even after this part of England was tied to the Duke of Brittany in right of his Richmond honour granted by the Duke of Normandy, who was King of all England, retained North Sea economy, especially with Flanders, in the woolens trade. This was, for a time, buttressed by the Anglo-Burgundian alliance that was essential for holding the Pale of Calais, lost by Mary I of England and Philip II of Spain in their disasterous war with France. Philip was titular Duke of Burgundy and his political opponent was William the Silent, whose son's actually welcomed rule (against Spain's overlordship) over the people was championed by Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, made Governor-General of the Dutch Republic under the terms of the Treaty of Nonsuch. These investments made by Elizabeth I of England would eventually influence the Royalty of England itself, under William III of England and continued by his Protestant Danish and German successors, whose own ties to mediaeval England, apart from Saxon heritage, were the Steelyard in London and the Hanseatic League's Kontor depots mostly on the German Ocean coast of England.

Genetic heritage

In 2000 the BBC conducted a genetic survey of the British Isles for its program 'Blood of the Vikings'. It concluded that Norse invaders settled sporadically throughout the British Isles with a particular concentration in certain areas, such as Orkney and Shetland[1]. This finding referred to Norwegian Vikings only, as descendants of Danish Vikings could not be distinguished from descendants of Anglo-Saxon settlers.[citation needed]

Archaeological sites and the Danelaw

Major archaeological sites that bear testimony to the Danelaw are few. The most famous is the site at York, which is often said to derive its name from the Old Norse Jórvík. (That name is itself a borrowing of the Old English Eoforwic; the Old English diphthong eo being cognate with the Norse diphthong jo, the Old English intervocalic f typically being pronounced softly as a modern v, and wic being the Old English version of the Norse vik.) Eoforwic in turn was derived from an earlier name for the town, spelled Eboracum in Latin sources. Another Danelaw site is the cremation site at Heath Wood, Ingleby, Derbyshire.

Archaeological sites do not bear out the historically defined area as being a real demographic or trade boundary. This could be due to misallocation of the items and features on which this judgment is based as being indicative of either Anglo-Saxon or Norse presence. Otherwise, it could indicate that there was considerable population movement between the areas, or simply that after the treaty was made, it was ignored by one or both sides.

Thynghowe was an important Danelaw meeting place, today located in Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire, England. The word "howe" often indicates a prehistoric burial mound. Howe is derived from the Old Norse work Haugr meaning mound.[10]

The site's rediscovery was made by Lynda Mallett, Stuart Reddish and John Wood. The site had vanished from modern maps and was essentially lost to history until the local history enthusiasts made their discoveries.

Experts think the rediscovered site, which lies amidst the old oaks of an area known as the Birklands in Sherwood Forest, may also yield clues as to the boundary of the ancient Anglo Saxon Kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria.

English Heritage, recently inspected the site and believes it is a national rarity. Thynghowe[2] was a place where people came to resolve disputes and settle issues. It is a Norse word, although the site may older still, perhaps even Bronze Age.

References

- ^ "The Old English word Dene ‘Danes’ usually refers to Scandinavians of any kind; most of the invaders were indeed Danish (East Norse speakers), but there were Norwegians (West Norse [speakers]) among them as well." —Lass, Roger, Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion, p.187, n.12. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- ^ Flores Historiarum: Rogeri de Wendover, Chronica sive flores historiarum, p. 298-9. ed. H. Coxe, Rolls Series, 84 (4 vols, 1841-42)

- ^ Haywood, John. The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings, p.62. Penguin Books. ©1995.

- ^ Carr, Michael. "Alfred the Great Strikes Back", p. 65. Military History Journal. June 2001.

- ^ Hadley, D. M. The Northern Danelaw: Its Social Structure, c. 800-1100. p. 310. Leicester University Press. ©2000.

- ^ The Kalender of Abbot Samson of Bury St. Edmunds, ed. R.H.C. Davis, Camden 3rd ser., 84 (1954), xlv-xlvi.

- ^ The Viking expansion

- ^ Falkus & Gillingham and Hill

- ^ J.L. Buckberry & D.M. Hadley, "An Anglo-Saxon Execution Cemetery at Walkington Wold, Yorkshire", Oxford Journal of Archaeology 26(3) 2007, 325

- ^ Guide to Scandinavian origins of place names in Britain

In literature

- Types of Manorial Structure in the Northern Danelaw, Frank M. Stenton, London, 1910.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Tiger Books International version translated and collated by Anne Savage,1995.