Diabetes

| Diabetes | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Diabetology |

Diabetes mellitus is a medical disorder characterized by varying or persistent hyperglycemia (elevated blood sugar levels), especially after eating. All types of diabetes mellitus share similar symptoms and complications at advanced stages. Hyperglycemia itself can lead to dehydration and ketoacidosis. Longer-term complications include cardiovascular disease (doubled risk), chronic renal failure (it is the main cause for dialysis), retinal damage which can lead to blindness, nerve damage which can lead to erectile dysfunction (impotence), gangrene with risk of amputation of toes, feet, and even legs. Serious complications are much less common in people who control their blood sugars well with lifestyle and medications.

The most important forms of diabetes are due to decreased or the complete absence of the production of insulin (type 1 diabetes), or decreased sensitivity of body tissues to insulin (type 2 diabetes, the more common form). The former requires insulin injections for survival; the latter is generally managed with diet, weight reduction and exercise in about 20% of cases, though the majority require these strategies plus oral medication (insulin is used if the tablets are ineffective).

Patient understanding and participation is vital, as blood glucose levels change continuously. Treatments that return the blood sugar to normal levels can reduce or prevent development of the complications of diabetes. Other health problems that accelerate the damaging effects of diabetes are smoking, elevated cholesterol levels, obesity, high blood pressure, and lack of regular exercise.

History

Although diabetes has been recognized since antiquity, and treatments were known since the Middle Ages, the elucidation of the pathogenesis of diabetes occurred mainly in the 20th century6.

Until 1921, when insulin was first discovered and made clinically available, a clinical diagnosis of what is now called type 1 diabetes was an invariable death sentence, more or less quickly. Non-progressing type 2 diabetics almost certainly often went undiagnosed then; many still do.

The discovery of the role of the pancreas in diabetes is generally credited to Joseph von Mering and Oskar Minkowski, two European researchers who in 1889 found that, when they completely removed the pancreas of dogs, the dogs developed all the signs and symptoms of diabetes and died shortly afterward. In 1910, Sir Edward Albert Sharpey-Schafer of Edinburgh in Scotland suggested that diabetics were deficient in a single chemical that was normally produced by the pancreas — he proposed calling this substance insulin.

The endocrine role of the pancreas in metabolism, and indeed the existence of insulin, was not fully clarified until 1921, when Sir Frederick Grant Banting and Charles Herbert Best repeated the work of Von Mering and Minkowski, but went a step further and managed to show that they could reverse the induced diabetes in dogs by giving them an extract from the pancreatic islets of Langerhans of healthy dogs7. They went on to isolate the hormone insulin from bovine pancreases at the University of Toronto in Canada.

This led to the availability of an effective treatment — insulin injections — and the first clinical patient was treated in 1922. For this, Banting et al received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1923. The two researchers made the patent available and did not attempt to control commercial production. Insulin production and therapy rapidly spread around the world, largely as a result of their decision.

The distinction between what is now known as type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes was made by Sir Harold Percival (Harry) Himsworth in 1935; he published his findings in January 1936 in The Lancet8.

Other landmark discoveries6 include:

- identification of sulfonylureas in 1942

- the radioimmunoassay for insulin, as discovered by Rosalyn Yalow and Solomon Berson (gaining Yalow the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine)

- Reaven's introduction of the metabolic syndrome in 1988

- identification of thiazolidinediones as effective antidiabetics in the 1990s

Causes and types

The role of insulin

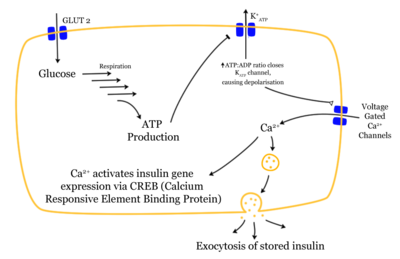

Since insulin is the principal hormone that regulates uptake of glucose into cells (primarily muscle and fat cells) from the blood, deficiency of insulin or its action plays a central role in all forms of diabetes.

Most of the carbohydrates in food are rapidly converted to glucose, the principal sugar in blood. Insulin is produced by beta cells in the pancreas in response to rising levels of glucose in the blood, as occurs after a meal. Insulin makes it possible for most body tissues to remove glucose from the blood for use as fuel, for conversion to other needed molecules, or for storage. Insulin is also the principal control signal for conversion of glucose (the basic sugar unit) to glycogen for storage in liver and muscle cells. Lowered insulin levels result in the reverse conversion of glycogen to glucose when glucose levels fall — though only glucose so produced in the liver goes into the blood. Higher insulin levels increase many anabolic ("building up") processes such as cell growth, cellular protein synthesis, and fat storage. Insulin is the principal signal in converting many of the bidirectional processes of metabolism from a catabolic to an anabolic direction.

If the amount of insulin available is insufficient, if cells respond poorly to the effects of insulin (insulin insensitivity or resistance), or if the insulin itself is defective, glucose is not handled properly by body cells (about 2/3 require it) or stored appropriately in the liver and muscles. The net effect is persistent high levels of blood glucose, poor protein synthesis, and other metabolic derangements.

Types

Type 1

Main article: Diabetes mellitus type 1

Type 1 diabetes (formerly known as insulin-dependent diabetes, childhood diabetes, or juvenile-onset diabetes) is most commonly diagnosed in children and adolescents, but can occur in adults, as well. It is characterized by β-cell destruction, which usually leads to an absolute deficiency of insulin. Most cases of type 1 diabetes are immune-mediated characterized by autoimmune destruction of the body's β-cells in the Islets of Langerhans of the pancreas, destroying them or damaging them sufficiently to reduce insulin production. However, some forms of type 1 diabetes are characterized by loss of the body's β-cells without evidence of autoimmunity.

Currently, type 1 diabetes is treated with insulin injections, lifestyle adjustments, and careful monitoring of blood glucose levels using blood test kits. Insulin delivery is also available by an insulin pump, which allows the infusion of insulin 24 hours a day at preset levels, and the ability to program push doses (bolus) of insulin as needed at meal times. The treatment must be continued indefinitely. During lifetime treatment that does not impair normal activities if carried out systematically with discipline, the average glucose level for the type I diabetic patient must be at 110 mg/dl–140 mg/dl as normal, although 150 mg/dl is acceptable. Some people prefer an average above 150 mg/dl. 200–250 mg/dl is the middle-range of high blood glucose when discomfort by a need to urinate begins at 170 mg/dl, though this is dependent on the individual's target range. 300–350 mg/dl requires a ketone analysis as well as insulin injections immediately. 350 mg/dl and above can lead to ketoacidosis if not treated with sugar-free liquids or water ideally consumed.

Type 2

Main article: Diabetes mellitus type 2

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by "insulin resistance," as body cells do not respond appropriately when insulin is present. This is a more complex problem than type 1 but is often easier to treat, since insulin is still produced, especially in the initial years. Type 2 may go unnoticed for years in a patient before diagnosis, since the symptoms are typically milder (no ketoacidosis) and can be sporadic. However, severe complications can result from unnoticed type 2 diabetes, including renal failure and coronary artery disease.

Type 2 is initially treated by changes in diet and through weight loss. This can restore insulin sensitivity, even when the weight lost is modest, e.g., around 5 kg (10 to 15 lb). The next step, if necessary, is treatment with oral antidiabetic drugs: the sulphonylureas, metformin, or (if these are insufficient) thiazolidinediones. If these fail, insulin therapy may be necessary to maintain normal glucose levels. Glucose levels at 140 mg/dl and above determine type 2 diabetes in prediabetic patients. For patients with diabetes, a disciplined regimen of blood glucose checks is required. To strive for better control in type 1 as well as type 2 diabetes, glucose levels must be checked periodically to maintain a high standard of care and quality of life.

Gestational diabetes

Main article: Gestational diabetes

Gestational diabetes mellitus appears in about 2%–5% of all pregnancies. It is temporary and fully treatable, but, if untreated, it may cause problems with the pregnancy, including macrosomia (high birth weight) of the child. It requires careful medical supervision during the pregnancy. In addition, about 20%–50% of these women go on to develop type 2 diabetes.

Other types

There are several causes of diabetes that do not fit into type 1, type 2, or gestational diabetes:

- Genetic defects in beta cells

- Genetically-related insulin resistance

- Diseases of the pancreas

- Hormonal defects

- Chemicals or drugs.

"Malnutrition-related diabetes mellitus" (MRDM or MMDM) was introduced by the WHO as the third major category of diabetes in the 1980s. However, in 1999, a WHO working group recommended that MRDM be deprecated, and proposed a new taxonomy for alternative forms of diabetes. Classification of non-type 1, non-type 2, non-gestational diabetes remains controversial.

Genetics

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are at least partly inherited. Type 1 diabetes appears to be triggered by infection, stress, or environmental factors (e.g., exposure to a causative agent). There is a genetic element in the susceptibility of individuals to some of these triggers which has been traced to particular HLA genotypes (i.e., genetic "self" identifiers used by the immune system). However, even in those who have inherited the susceptibility, type 1 diabetes mellitus seems to require an environmental trigger. A small proportion of type 1 diabetics carry a mutation that causes maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY).

There is an even stronger inheritance pattern for type 2 diabetes: those with type 2 ancestors or relatives have very much higher chances of developing type 2. Concordance among monozygotic twins is close to 100%, and 25% of those with the disease have a family history of diabetes. It is also often connected to obesity, which is found in approximately 85% of (North American) patients diagnosed with that form of the disease, so some experts believe that inheriting a tendency toward obesity seems also to contribute. However, working in concert with genetic predisposition, many experts believe that lifestyle factors (lack of exercise, poor diet, etc.) are the greatest contributors to the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and that stringent weight control in persons with a genetic predisposition will effectively prevent and ameliorate the pathology of the disease in most cases. Age is also thought to be a contributing factor, as most type 2 patients in the past were older. The exact reasons for these connections are unknown.

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms

Type 2 diabetes almost always has a slow onset (often years), but, in type 1, particularly in children, onset may be quite fast (weeks or months). Early symptoms of type 1 diabetes are often polyuria (frequent urination) and polydipsia (increased thirst, and consequent increased fluid intake). There may also be weight loss (despite normal or increased eating), increased appetite, and irreducible fatigue. These symptoms may also manifest in type 2 diabetes in patients whose diabetes is poorly controlled.

Thirst develops because of osmotic effects—sufficiently high glucose (above the "renal threshold") in the blood is excreted by the kidneys, but this requires water to carry it and causes increased fluid loss, which must be replaced. The lost blood volume will be replaced from water held inside body cells, causing dehydration.

Another common-presenting symptom is altered vision. Prolonged high blood glucose causes changes in the shape of the lens in the eye, leading to blurred vision and, perhaps, a visit to an optometrist. All unexplained quick changes in eyesight should force a fasting blood glucose test. These are now quick (10 seconds), using inexpensive materials (less than USD $1), and can be safely performed by almost anyone with minimal training.

Especially-dangerous symptoms in diabetics include the smell of acetone on the patient's breath (a sign of ketoacidosis), Kussmaul breathing (a rapid, deep breathing), and any altered state of consciousness or arousal (hostility and mania are both possible, as is confusion and lethargy). The most dangerous form of altered consciousness is the so-called "diabetic coma," which produces unconsciousness. Early symptoms of impending diabetic coma include polyuria, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, with lethargy and somnolence a later development, progressing to unconsciousness and death if untreated.

Diagnostic approach

The diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and many cases of type 2 is usually prompted by recent-onset symptoms of excessive urination (polyuria) and excessive thirst (polydipsia), often accompanied by weight loss. These symptoms typically worsen over days to weeks; about 25% of people with new type 1 diabetes have developed a degree of diabetic ketoacidosis by the time the diabetes is recognized.

The diagnosis of other types of diabetes is made in many other ways. The most common are (1) health screening, (2) detection of hyperglycemia when a doctor is investigating a complication of longstanding, unrecognized diabetes, and (3) new signs and symptoms attributable to the diabetes.

- Diabetes screening is recommended for many types of people at various stages of life or with several different risk factors. The screening test varies according to circumstances and local policy and may be a random glucose, a fasting glucose and insulin, a glucose two hours after 75 g of glucose, or a formal glucose tolerance test. Many healthcare providers recommend universal screening for adults at age 40 or 50, and sometimes occasionally thereafter. Earlier screening is recommended for those with risk factors such as obesity, family history of diabetes, high-risk ethnicity (Hispanic [Latin American], American Indian, African American, Pacific Island, and South Asian ancestry).

- Many medical conditions are associated with a higher risk of various types of diabetes and warrant screening. A partial list includes: high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol levels, coronary artery disease, past gestational diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, chronic pancreatitis, hepatic steatosis (fatty liver), cystic fibrosis, several mitochondrial neuropathies and myopathies, myotonic dystrophy, Friedreich's ataxia, some of the inherited forms of neonatal hyperinsulinism, and many others. Risk of diabetes is higher with chronic use of several medications, including high-dose glucocorticoids, some chemotherapy agents (especially L-asparaginase), and some of the antipsychotics and mood stabilizers (especially phenothiazines and some atypical antipsychotics).

- Diabetes is often detected when a person suffers a problem frequently caused by diabetes, such as a heart attack, stroke, neuropathy, poor wound healing or a foot ulcer, certain eye problems, certain fungal infections, or delivering a baby with macrosomia or hypoglycemia.

Criteria for diagnosis

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by recurrent or persistent hyperglycemia, and is diagnosed by demonstrating any one of the following:

- fasting plasma glucose level at or above 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL)

- plasma glucose at or above 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) two hours after a 75 g glucose load

- symptoms of diabetes and a random plasma glucose at or above 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL).

A positive result should be confirmed by any of the above-listed methods on a different day, unless there is no doubt as to the presence of significantly-elevated glucose levels. Most physicians prefer measuring a fasting glucose level because of the ease of measurement and time commitment of formal glucose tolerance testing, which can take two to three hours to complete. By definition, two fasting glucose measurements above 126 mg/dL is considered diagnostic for diabetes mellitus.

Because of the usefulness of dietary and lifestyle changes in the natural course of diabetes, patients with fasting blood sugars between 100 and 125 mg/dL are considered to have "impaired fasting glucose," which many physicians consider "prediabetes" and a major risk factor for progression to full-blown diabetes mellitus. A postprandial (2 hours after eating) blood sugar between 140 and 199 mg/dL is called "glucose intolerance" and is also a "prediabetic" diagnosis.

While not used for diagnosis, an elevated glucose bound to hemoglobin, HbA1c, of 6.0% or higher (2003 revised U.S. standard) is considered abnormal by most labs; HbA1c is primarily a treatment-tracking test reflecting average blood glucose levels over the preceding 90 days (approximately). However, some physicians may order this test at the time of diagnosis to track changes over time. The current recommended goal for HbA1c in patients with diabetes is <7.0%, as defined as "good glycemic control," although stricter guidelines may be adopted soon (<6.5%). Diabetics that have HbA1c levels at goal have a significantly lower incidence of complications from diabetes, including retinopathy and diabetic nephropathy.

Glucose Monitoring

Control and outcome in type 1 diabetes is improved by patients using glucometers to measure their glucose levels regularly. Some patients are reluctant to use these devices for various reasons; they are useful only if changes in sugar levels produce changes in behavior — chiefly with regard to eating and injecting insulin. And, although the devices are marketed to patients with type 2 diabetes, there is a lack of evidence of effectiveness there, and a certainty that more benefit could be had from that cost if it were spent on treatment and other assistance.

Diabetic ketoacidosis and coma

See more detail in the articles diabetic ketoacidosis and diabetic coma

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is an acute, dangerous complication and is always a medical emergency. Prompt proper treatment usually results in full recovery, though death can result from inadequate treatment or a variety of complications.

Hyperosmotic diabetic coma is another acute problem associated with improper management of diabetes mellitus. It has some symptoms in common with DKA, but a different cause, and requires different treatment. In anyone with very high blood glucose levels (usually considered to be above 16.6 mmol/l [300 mg/dl]), water will be osmotically driven out of cells into the blood. The kidneys will also be "dumping" glucose into the urine, resulting in concomitant loss of water, causing an increase in blood osmolality. The osmotic effect of high glucose levels combined with the loss of water will eventually result in such a high serum osmolality that the body's cells may become directly affected as water is drawn out from them. Electrolyte imbalances are also common. This combination of changes, especially if prolonged, will result in symptoms similar to ketoacidosis, including loss of consciousness. As with DKA urgent medical treatment is necessary. This is the diabetic coma to which type 2 diabetics are prone; it is less common in type 1 diabetics.

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes almost always arises as a result of poor management of the disease, either from too much or poorly timed insulin or oral hypoglycemics or too much exercise, not enough food, or poor timing of either. If blood glucose levels are low enough, the patient may become agitated, sweaty, and have many symptoms of sympathetic activation of the autonomic nervous system—they may experience feelings similar to dread and immobilized panic. Consciousness can be altered, or even lost, in extreme cases, leading to coma and/or seizures or even brain damage and death. Experienced diabetics can often recognize the symptoms early on—all diabetics should always carry something sugary to eat or drink as these symptoms can be rapidly reduced if treated early enough. In the case of children, this can be a type of candy disliked by the patient, to prevent concerns about unnecessary use.

Other ways of treating hypoglycemia include an intra muscular injection of glucagon, which causes the liver to convert its internal stores of glycogen to be released as glucose into the blood. Oral or intravenous dextrose can also be given. In most cases recovery is rapid and trouble free. Longstanding hypoglycemia may require hospital admission to allow supervised recovery and adjustment of diabetic medications.

Long-term complications

Among the major risks of the disorder are chronic problems affecting multiple organ systems which will eventually arise in patients with poor glycemic control. Many of these arise from damage to the blood vessels. These illnesses can be divided into those arising from large blood vessel disease, macroangiopathy, and those arising from small blood vessel disease, microangiopathy. Interestingly, small vessel disease is minimized by tight blood glucose control, but large vessel disease is unaffected by tight blood glucose control.

- Small vessel disease complications:

- Proliferative retinopathy and macular edema, which can lead to severe vision loss or blindness

- Peripheral neuropathy, which, particularly when combined with damaged blood vessels, can lead to foot ulcers and possibly progressing to necrosis, infection and gangrene, sometimes requiring limb amputation, see below

- Diabetic nephropathy (due to microangiopathy) which can lead to renal failure

- Large vessel disease complications:

- Ischemic heart disease caused by both large and small vessel disease

- Stroke

- Peripheral vascular disease, which contributes to foot ulcers and the risk of amputation

Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of adult kidney failure worldwide. It also the most common cause of amputation in the U.S., usually toes and feet, often as a result of gangrene, and almost always as a result of peripheral vascular disease. Retinal damage (from microangiopathy) makes it the most common cause of blindness among non-elderly adults in the U.S. A number of studies have found that those with diabetes are more at risk for dry eye syndrome![]() Administrator note

Administrator note![]() Administrator note

Administrator note![]() Administrator note. Advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs) are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of angiopathy resulting from diabetes mellitus.

Administrator note. Advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs) are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of angiopathy resulting from diabetes mellitus.

Management of the disease

Main article: Diabetes management

Diabetes is a chronic disease with no cure (except experimentally in type 1 diabetics) as of 2006. Management of this disease may include lifestyle modifications such as achieving and maintaining proper weight, diet, exercise and foot care. Additionally, it may involve the use of oral medications or insulin therapy. In the case of type 1, insulin therapy is pretty much a given.

In addition, self-monitoring via self-administered glucose testing using a glucose monitor is an essential element of any diabetes management program. The success in management can be monitored by measuring the proportion of the HbA1c variant of hemoglobin.

Curing diabetes

A disease consisting of the failure of a single organ (type 1 diabetes, the Islets of Langerhans) with a relatively simple function points at the cure. Type 2 diabetes is more complex and difficult, but to the extent it is regarded as an excursion by the organism from the control envelope of the metabolic functions around glucose metabolism, correcting body mass to reverse that excursion approaches a cure. Unfortunately this rarely occurs, and failure of the Islets also occurs in type 2 diabetes.

At present cures for islet cell failure are experimental or theoretical; however, recent developments strongly suggest they should be achievable. Political and religious complications may arise in some states.

Biological

The most obvious approach is to replace the failed organ with more islet cells. A transplant of exogenous cells will provoke an immune reaction unless they are either perfectly tissue matched to the recipient or enclosed to isolate them from the immune system. Stem cell techniques and possibly genetic engineering offer the former, but as of 2005 this is not yet a working set of techniques. The latter has been experimentally demonstrated in humans, with membrane encapsulated clumps of islet cells injected in to the peritoneal cavity. The membrane must allow oxygen and sugar in and insulin out, but not permit immunoglobulin molecules to get in. Since the cells have not lasted for prolonged periods, this technique may become merely part of the mechanism of use of a stem cell/cell culture source.

An alternative is placement of loose (unencapsulated) cells into the liver, via the hepatic blood supply. Work at Kings College Hospital in London, UK, has demonstrated cells can settle and perform in that milieu.

Mechanical

A microscopic or nanotechnological approach, with implanted stores of insulin metered out by a rapidly sensitive glucose measure, would approach a cure, but is currently beyond available technology.

Public health, policy and health economics

The Declaration of St Vincent was the result of international efforts to improve the care accorded to diabetics. Doing so is important if only economically. Diabetes is enormously expensive for healthcare systems and governments. In North America it is the largest single non-traumatic cause in adults of amputation, blindness, and dialysis, all extremely expensive events.

Work in the Puget Sound area of North America (by the health organization Group Health) shows that, over its large and varied patient population, specially retaining medical information on diabetic patients, keeping it up to date, and basing their continuing care on that data reduced total healthcare costs for those patients by US$1000 per year per patient for the rest of life. Recognition of this reality drove the Hawkes Bay initiative which established such a system, and resulted in various activities throughout the world including the Black Sea Telediab project, which produced elements of a distributed diabetic record and management system as an open source computer program.

Some researchers believe breast-feeding may protect children from developing diabetes. Research published in JAMA in November 2005 also suggests that breast-feeding might also be correlated with the prevention of the disease in mothers. The study found that the women's risk of developing diabetes was reduced the longer they nursed.

Statistics

In 2004, according to the World Health Organization, more than 150 million people worldwide suffered from diabetes. Its incidence is increasing rapidly, and it is estimated that by the year 2025, this number will double. Diabetes mellitus occurs throughout the world, but is more common (especially type 2) in the more developed countries. The greatest increase in prevalence is, however, expected to occur in Asia and Africa, where most of the diabetic patients will be seen by 2025. The increase in incidence of diabetes in the developing countries follows the trend of urbanization and lifestyle changes.

Diabetes is in the top 10, and perhaps the top 5, of the most significant diseases in the developed world, and is gaining in significance (see big killers).

For at least 20 years, diabetes rates in North America have been increasing substantially. In 2005 there are about 20.8 million people with diabetes in the United States alone. According to the American Diabetes Association, there are about 6.2 million people undiagnosed and about 41 million people that would be considered prediabetic. The Centers for Disease Control has termed the change an epidemic. The National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse estimates that diabetes costs $132 billion in the United States alone every year. About 5%–10% of these cases of diabetes are type 1 diabetics. The fraction of type 1 diabetics in other parts of the world differs; this is likely due to both differences in the rate of type 1 and differences in the rate of other types, most prominently type 2. Most of this difference is not currently understood.

Etymology

The word diabetes was coined by Aretaeus (81–133 CE) of Cappadocia. The word is taken from Greek diabaínein, and literally means "passing through", or "siphon", a reference to one of the diabetes major symptoms of excessive urine discharge. The word became "diabetes" from the English adoption of the medieval Latin diabetes. In 1675 Thomas Willis added mellitus to the name (Greek mel, "honey", sense "honey sweet") when he noted that a diabetic's urine and blood has a sweet taste (first noticed by ancient Indians). In 1776 it was confirmed the sweet taste was because of an excess of sugar in the urine and blood.

The ancient Chinese tested for diabetes by observing whether ants were attracted to a person's urine, and called the ailment "sweet urine disease" (糖尿病); medieval European doctors tested for it by tasting the urine themselves, a scene occasionally depicted in Gothic reliefs.

It is probably important to note that passing abnormal amounts of urine is a symptom shared by several diseases (most commonly of the kidneys), and the single word diabetes is applied to many of them. The most common of them are diabetes insipidus and the subject of this article, diabetes mellitus.

References

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977-86. Fulltext. PMID 8366922.

- World Health Organisation, Department of Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications. Geneva: WHO, 1999 (PDF)

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998;352:837-53. PMID 9742976.

- Conditions in Occupational Therapy: effect on occupational performance. Edited by Ruth A. Hansen and Ben Atchison. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Williams, 2000;298-309. ISBN 0-683-30417-8.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin in 5963 people with diabetes: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361(9374):2005-16. PMID 12814710.

- Patlak M. New Weapons to Combat an Ancient Disease: Treating Diabetes. FASEB J 2002;16:1853E. PMID 12468446.

- Banting FG, Best CH, Collip JB, Campbell WR, Fletcher AA. Pancreatic extracts in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Canad Med Assoc J 1922;12:141-146.

- Himsworth HP. Diabetes mellitus: its differentiation into insulin-sensitive and insulin-insensitive types. Lancet 1936;i:127-130.

- Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, Hitman GA, Neil HA, Livingstone SJ, Thomason MJ, Mackness MI, Charlton-Menys V, Fuller JH on behalf of the CARDS Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 685-96. PMID 15325833

- MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 2002; 360: 7-22. PMID 12114036

- Template:AnbKaiserman I, Kaiserman N, Nakar S, Vinker S. Dry eye in diabetic patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Mar;139(3):498-503. PMID 15767060

- Template:AnbLi HY, Pang GX, Xu ZZ. [Tear film function of patients with type 2 diabetes]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2004 Dec;26(6):682-6. PMID 15663232

- Template:AnbSendecka M, Baryluk A, Polz-Dacewicz M. [Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye syndrome]. Przegl Epidemiol. 2004;58(1):227-33. PMID 15218664

- Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Manson JE, Michels KB. Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2005;294:2601-10. PMID 16304074.

- American Diabetes Association. "Total Prevalence of Diabetes and Pre-diabetes." www.diabetes.org/diabetes-statistics/prevalence.jsp

- Anne Underwood, "Living Longer, Better," Newsweek January 16 issue, copyright 2006[1]

- Joe and Terry Graedon,Vinegar and Cinnamon Lower Blood Sugar November 7, 2005

See also

- List of terms associated with diabetes

- List of celebrities with diabetes

- Diabetes in cats and dogs

- Hyperglycemia