Divergent evolution: Difference between revisions

→Divergent versus parallel evolution: Wording changed. |

→Darwin's finches: Wording updated, additional information added, and sources added. |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

== Darwin's finches == |

== Darwin's finches == |

||

{{unsourced section|date=March 2024}} |

{{unsourced section|date=March 2024}} |

||

One of the first recorded examples of divergent evolution is the case of [[Darwin's Finches]]. During Darwin's travels to the Galápagos Islands, he discovered several different species of finch, living on the different islands. Darwin observed that the finches had different beaks specialized for that species of finches' diet.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Desmond |first=Adrian J. |title=Darwin |last2=Moore |first2=James R. |date=1991 |publisher=Joseph |isbn=978-0-7181-3430-3 |edition=1. publ |location=London}}</ref> Some finches had short powerful beaks for breaking and eating nuts, other finches had long thin beaks for eating insects, and others had breaks specialized for eating cacti and other plants.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Grant |first=Peter R. |title=Ecology and evolution of Darwin's finches |date=1999 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-04865-9 |location=Princeton, N.J}}</ref> He concluded that the finches evolved from a shared common ancestor that lived on the islands, and due to geographic isolation, evolved to fill the particular niche on each the island.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Grant |first=Peter R. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/ocm82673670 |title=How and why species multiply: the radiation of Darwin's finches |last2=Grant |first2=B. Rosemary |date=2008 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-13360-7 |series=Princeton series in evolutionary biology |location=Princeton |oclc=ocm82673670}}</ref> This is supported by modern day genomic sequencing.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lamichhaney |first=Sangeet |last2=Berglund |first2=Jonas |last3=Almén |first3=Markus Sällman |last4=Maqbool |first4=Khurram |last5=Grabherr |first5=Manfred |last6=Martinez-Barrio |first6=Alvaro |last7=Promerová |first7=Marta |last8=Rubin |first8=Carl-Johan |last9=Wang |first9=Chao |last10=Zamani |first10=Neda |last11=Grant |first11=B. Rosemary |last12=Grant |first12=Peter R. |last13=Webster |first13=Matthew T. |last14=Andersson |first14=Leif |date=2015-02 |title=Evolution of Darwin’s finches and their beaks revealed by genome sequencing |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14181 |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=518 |issue=7539 |pages=371–375 |doi=10.1038/nature14181 |issn=1476-4687}}</ref> |

|||

One of the most famous examples of divergent evolution is the case of [[Darwin's finches]]. During Darwin's travels to the Galápagos Islands he discovered several different species of finch that shared a common ancestor. They lived on varying diets and had beaks that differed in shape and size reflecting their diet. The changes in beak shape and size were believed to be required to support their change in diet. Some Galápagos finches have larger and more powerful beaks to crack nuts with. A different type allows the bird to use cactus spines to spear insects in the bark of trees. |

|||

==Divergent evolution in dogs== |

==Divergent evolution in dogs== |

||

Revision as of 18:58, 24 March 2024

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

Divergent evolution or divergent selection is the accumulation of differences between closely related populations within a species, sometimes leading to speciation. Divergent evolution is typically exhibited when two populations become separated by a geographic barrier (such as in allopatric or peripatric speciation) and experience different selective pressures that cause adaptations. After many generations and continual evolution, the populations become less able to interbreed with one another.[1] The American naturalist J. T. Gulick (1832–1923) was the first to use the term "divergent evolution",[2] with its use becoming widespread in modern evolutionary literature. Examples of divergence in nature are the adaptive radiation of the finches of the Galapagos, changes in mobbing behavior of the kittiwake, and the evolution of the modern-day dog from the wolf.

The term can also be applied in molecular evolution, such as to proteins that derive from homologous genes. Both orthologous genes (resulting from a speciation event) and paralogous genes (resulting from gene duplication) can illustrate divergent evolution. Through gene duplication, it is possible for divergent evolution to occur between two genes within a species. Similarities between species that have diverged are due to their common origin, so such similarities are homologies.

Causes

Animals undergo divergent evolution for a number of reasons linked to changes in environmental or social pressures. This could include changes in the environment, such access to food and shelter. It could also result from changes in predators, such as new adaptations, an increase or decrease in number of active predators, or the introduction of new predators. Divergent evolution can also be a result of mating pressures such as increased competition for mates or selective breeding by humans.

Distinctions

Divergent evolution is a type of evolution and is distinct from convergent evolution and parallel evolution, although it does share similarities with the other types of evolution.

Divergent versus convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the development of analogous structures that occurs in different species as a result of those two species facing similar environmental pressures and adapting in similar ways. It differs from divergent evolution as the species involved do not descend from a closely related common ancestor and the traits accumulated are similar. An example of convergent evolution is the development of flight in birds, bats, and insects, all of which are not closely related but share analogous structures allowing for flight.

Divergent versus parallel evolution

Parallel evolution is the development of a similar trait in species descending from a common ancestor. It is comparable to divergent evolution in that the species are descend from a common ancestor, but the traits accumulated are similar due to similar environmental pressures while in divergent evolution the traits accumulated are different. An example of parallel evolution is that certain arboreal frog species, 'flying' frogs, in both Old World families and New World families, have developed the ability of gliding flight. They have "enlarged hands and feet, full webbing between all fingers and toes, lateral skin flaps on the arms and legs, and reduced weight per snout-vent length".[3]

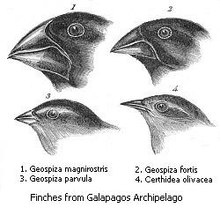

Darwin's finches

One of the first recorded examples of divergent evolution is the case of Darwin's Finches. During Darwin's travels to the Galápagos Islands, he discovered several different species of finch, living on the different islands. Darwin observed that the finches had different beaks specialized for that species of finches' diet.[4] Some finches had short powerful beaks for breaking and eating nuts, other finches had long thin beaks for eating insects, and others had breaks specialized for eating cacti and other plants.[5] He concluded that the finches evolved from a shared common ancestor that lived on the islands, and due to geographic isolation, evolved to fill the particular niche on each the island.[6] This is supported by modern day genomic sequencing.[7]

Divergent evolution in dogs

Another good example of divergent evolution is the origin of the domestic dog and the modern wolf. Dogs and wolves both diverged from a common ancestor.[8] The similarity of the mitochondrial DNA sequences from 162 wolves from various parts of the world and 140 dogs of 60 different breeds, revealed by genomic research, further supported the theory that dogs and wolves have diverged from shared ancestry.[9] Dogs and wolves have similar body shape, skull size, and limb formation, further supporting their close genetic makeup and thus shared ancestry.[10] For example, malamutes and huskies are physically and behaviorally similar to wolves. Huskies and malamutes have very similar body size and skull shape. Huskies and wolves share similar coat patterns as well as tolerance to cold. In the hypothetical situations[clarification needed], mutations and breeding events were simulated to show the progression of the wolf behavior over ten generations. The results concluded that even though the last generation of the wolves were more docile and less aggressive, the temperament of the wolves fluctuated greatly from one generation to the next.[11]

See also

References

- ^ "Sympatric speciation". Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^

Gulick, John T. (September 1888). "Divergent Evolution through Cumulative Segregation". Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Zoology. 20 (120): 189–274. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1888.tb01445.x. Retrieved 26 September 2011. (subscription required)

Gulick, John T. (September 1888). "Divergent Evolution through Cumulative Segregation". Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Zoology. 20 (120): 189–274. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1888.tb01445.x. Retrieved 26 September 2011. (subscription required)

- ^ Emerson, S.B.; M.A.R. Koehl (1990). "The interaction of behavioral and morphological change in the evolution of a novel locomotor type: 'Flying' frogs". Evolution. 44 (8): 1931–1946. doi:10.2307/2409604. JSTOR 2409604. PMID 28564439.

- ^ Desmond, Adrian J.; Moore, James R. (1991). Darwin (1. publ ed.). London: Joseph. ISBN 978-0-7181-3430-3.

- ^ Grant, Peter R. (1999). Ecology and evolution of Darwin's finches. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04865-9.

- ^ Grant, Peter R.; Grant, B. Rosemary (2008). How and why species multiply: the radiation of Darwin's finches. Princeton series in evolutionary biology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13360-7. OCLC 82673670.

- ^ Lamichhaney, Sangeet; Berglund, Jonas; Almén, Markus Sällman; Maqbool, Khurram; Grabherr, Manfred; Martinez-Barrio, Alvaro; Promerová, Marta; Rubin, Carl-Johan; Wang, Chao; Zamani, Neda; Grant, B. Rosemary; Grant, Peter R.; Webster, Matthew T.; Andersson, Leif (2015-02). "Evolution of Darwin's finches and their beaks revealed by genome sequencing". Nature. 518 (7539): 371–375. doi:10.1038/nature14181. ISSN 1476-4687.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Vila, C., JE Maldonado, and RK Wayne. 1999. Phylogenetic Relationships, Evolution, and Genetic Diversity of the Domestic Dog. J Hered 90:71-77

- ^ Vila C., P. Savolainen, J.E. Maldonado, I.R. Amorim, J.E. Rice, R.L. Honeycutt, K.A. Crandall, J. Lundeberg, and R.K. Wayne. 1997. Multiple and Ancient Origins of the Domestic Dog. Science 13 Vol. 276, no. 5319: 1687–1689

- ^ Honeycutt, Rodney L. (2010). "Unraveling the mysteries of dog evolution". BMC Biology. 8: 20. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-20. PMC 2841097. PMID 20214797.

- ^ Romanchik, J. 2011. From the Wild Wolf to Man’s Best Friend:An Analysis of a Hypothetical Wolf Population and the Change in Temperament, Possibly Leading to Their Domestication. Old Dominion University http://d2oqb2vjj999su.cloudfront.net/users/000/082/618/962/attachments/Scientific%20Paper-%20Wolves%20to%20Dogs.pdf Archived 2014-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Jonathan B. Losos (2017). Improbable Destinies: Fate, Chance, and the Future of Evolution. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-0399184925.